Neha A

Introduction

Michel-Rolph Trouillot lays bare the ways power enters the archive across four specific moments: fact creation, fact assembly, fact retrieval, and retrospective significance. Tina Turner navigated power in the archive by actively creating and assembling facts through her performances, media engagements, and autobiographies; she ensured their retrieval by embedding a record of her career and interior life into the cultural memory; lastly, she shaped retrospective significance by reclaiming her sexuality and openly addressing issues of domestic violence. Tina Turner’s career exemplified a mode of expression that is at once deeply personal and broadly political, engaging with themes of sexuality, public music performance, and the intersection of race and gender as a means of liberatory politics. In this way, she challenged traditional archival silences surrounding black womanhood, changing how black female agency is perceived. Thus, through an exploration of her public archive, this project uncovers how Tina Turner’s life and career fill archival silences and what it signifies for a black woman to have her life so intensely documented and examined.

Historical Context

Tina Turner rose to fame during a pivotal era of racial and gender transformation in the United States, coinciding with the civil rights movement and the second feminist wave of the 1960s and 1970s that sought to redefine women’s role in society. Toni Morrison, in her 1971 New York Times article, critiqued the Women’s Liberation Movement, largely led by white women, for its failure to fully encompass the lived experiences of black women (Morrison). Echoing Morrison, Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman in Congress, articulated the unique challenges faced by black women in her 1974 campaign speech titled “The Black Woman in Contemporary America.” She explained how these challenges are often overlooked by both the black and feminist movements, leading to a surge in black women’s social and political activism (Chisholm). A photograph from the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., captures the determined spirit of numerous black women protesting on the streets, holding signs that demanded justice, equality, and the right to vote (Leffler). This visual demonstrates black women’s significant contributions to the civil rights movement at the nexus of gender and racial activism. Additionally, the sexual revolution of the same era further complicated the landscape in which Tina Turner’s career evolved, intersecting with the burgeoning movements for civil rights and women’s liberation. Music, as a powerful form of cultural expression, played a significant role in fueling the sexual revolution, challenging traditional norms surrounding sexuality and personal freedom (Kemp).

Amidst this complex sociopolitical landscape, Tina Turner’s emergence as a force in the music industry was more than just a personal victory; it was emblematic of the broader potential for black female artists and women to construct their own archives and achieve recognition (Mafe). In a 1984 interview with CBS News, Turner reflected on the compounded forms of oppression she had to navigate as a Black woman, stating that:

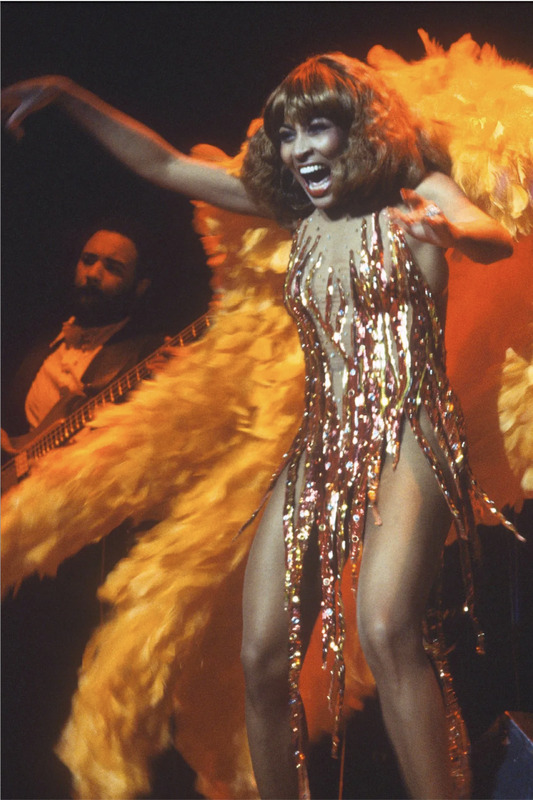

Breaking through racial and gender barriers, she became the first woman and the first Black artist to appear on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine in 1967 (Parker). The still captured from Tina Turner’s live performance, showcasing her muscular arms and sequin dress, with her face and body drenched in sweat, radiates her visual power. This was not just style for the sake of glamour but a strategic positioning of her identity, where fashion allowed her to frame her brand of performance and challenge archival silences around black glamour in the mainstream media (Moore, 72). Her two inductions into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, first with Ike Turner in 1991 and later as a solo artist in 2021, demonstrate her enduring sonic and cultural legacy. The Hall of Fame’s Tina Turner Archive––which includes pictures, books, articles, videos, interviews, podcasts, and a Spotify playlist of her biggest hits––not only makes fact retrieval of her contributions easily accessible but also highlights their retrospective significance (“Tina Turner”).

Eroticism as Defiance

Tina Turner used eroticism in her performances and fashion as a form of emancipatory politics, expanding the discourse around black femininity, sexuality, and agency. Even in the midst of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, respectable Black women were supposed to occupy a certain musical space; Turner’s embrace of rock music liberated her from these genre-based racialized confines, ultimately helping her attain mainstream visibility and commercial success. Her live performances, such as the iconic opening of “I Wanna Take You Higher” in 1971, were characterized by explosive sexual energy and a “fierceness” that truly set her apart as a disruptive force in the performance world (Moore 72). This “fierceness,” defined by her transgressive self-expression and aesthetic boldness, revolutionized performance art by blending glamour and the physicality of resistance into a cohesive act of defiance (Moore 72). One of the most memorable examples of this was her legendary live rendition of “Proud Mary.” Tina Turner’s interpretation transformed the song into a high-octane rock and roll performance, with her vigorous dance moves and sultry vocals mesmerizing both black and white audiences. In another instance, during a performance with Mick Jagger at Live Aid in Philadelphia in 1985, she tore off her skirt mid-act––a bold statement of sexual liberation. She changed the performance culture for women, making dynamic sensuality palatable on stage and television in the late 1960s (Myers).

Tina Turner’s stage outfits themselves also demonstrated her embrace of eroticism as empowerment, contributing to her sartorial legacy. From her signature sequin or fringe mini dresses and high heels that highlighted her famously long legs to her later, more elaborate stage costumes, Tina Turner used fashion to enhance her dynamic performances, ensuring that her physical expression matched the intensity of her music (Botelho). One of her most iconic looks was the red and gold flame dress from a stage performance in 1979, which was designed to “sparkle like dynamite,” perfectly encapsulating her fiery stage presence (Périer). The notion that her “fierceness remains” regardless of the medium—be it print, sound, or video—exemplifies Turner’s consistent defiance through her aesthetics, filling archival silences of black glamour and sensuality (Moore 73).

Tina Turner’s dynamism on stage and invocation of the erotic marked a reclamation of black women’s sexual narratives in the context of a long history of racialized and gendered denigration. Historians have documented tropes of African women as savage and hypersexualized as early as the sixteenth century, a portrayal that served as a justification for their exploitation and supported the broader objectives of colonialism. European narratives often sexualized and demonized African women, using their bodies—particularly their breasts—as markers of racial and cultural difference, thereby justifying their subjugation and exploitation. This historical backdrop made Tina Turner’s reclamation of her sexuality on her own terms not only radical but deeply subversive. It was a direct challenge to the legacy of viewing black women’s bodies solely through the lens of reproduction and capital. Furthermore, it asserted black women’s right to occupy proper spaces of femininity and to participate in the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Furthermore, this narrative of resistance and power, which Tina Turner wove through her music and performance, offered a model of how black women could confront and overcome systemic constraints, inspiring a collective reimagining of what it means to be both empowered and authentic in the public archive. Thus, her performances were not just entertainment; they were physical acts of resistance disrupting historical narratives imposed on black women’s bodies.

Reclaiming her Narrative

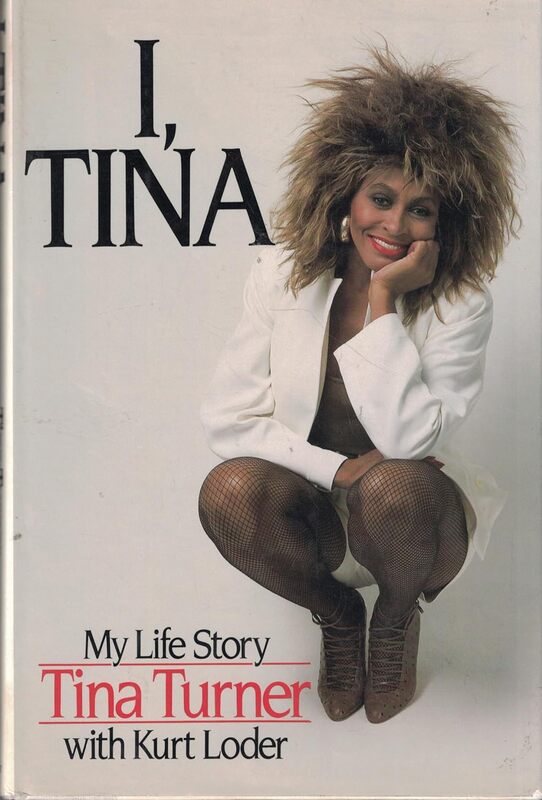

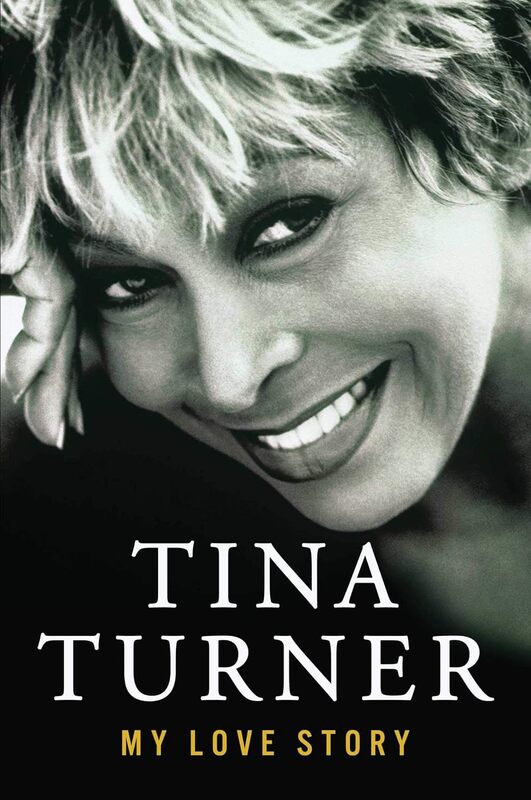

Tina Turner offered insights into the struggles of her interior life, filling archival silences about domestic violence and shaping retrospective significance. In 1986, she published her autobiography, I, Tina co-authored with Kurt Loder, and the follow-up My Love Story in 2018, where she wrote about her abusive relationship with Ike Turner and her personal liberation post-divorce. During their relationship, Ike physically assaulted her, beating her with wooden shoe stretchers and hangers, sometimes landing her in the hospital (O’Neil). She also explained how he emotionally manipulated, verbally abused, and sexually assaulted her during their marriage (O’Neil). Additionally, he managed all financial aspects of their career, leaving Tina with no control over the money she earned, and purposefully isolated her from her family and friends (O’Neil). During Ike’s abuse, Tina Turner sought solace in prayer and meditation, cultivating a profound inner strength. This newfound power enabled her to reclaim her identity and establish a unique expression of Black femininity, rejecting traditional notions of submissiveness and embracing a new persona characterized by bold resistance (Turner, 162).

In a 1997 interview with Oprah Winfrey, she spoke openly about the complexities of her experiences with abuse and her eventual freedom, theorizing this freedom in the context of separation from physical harm. She explains that:

Her post-Ike renaissance on stage in the 1980s challenged the construction of the erotically dangerous black women’s body, transforming these narratives into expressions of personal and collective liberation, which ultimately culminated in the most successful period of her career (Royster, 78).

By laying bare her personal struggles, she constructed her public archive and contributed to a broader cultural shift. In the early 1980s, the prevailing belief was that domestic violence was an issue exclusive to economically disadvantaged women without the resources to leave. Tina Turner’s candidness played a critical role in shifting the narrative on who could be a victim of such abuse, empowering other victims to speak out against their abuse (Bushby). This case emerged during a significant period when sustained feminist efforts were beginning to alter public and legal perspectives on gender-based violence. Feminist activism helped to illustrate domestic violence not as a private or isolated issue but as a systemic societal problem requiring public and legal intervention. By bringing attention to the severity and prevalence of domestic abuse, Tina Turner’s voice was crucial in helping shift societal attitudes, leading to greater legal protections for victims, such as the eventual acceptance of the battered woman syndrome in court defenses in the 1990s, and a broader societal understanding of the complexities surrounding gender-based violence (Bushby). Thus, by reclaiming her narrative, Tina Turner disrupted the archival silences that surrounded this topic and resisted the “acts of violence in the narration itself,” as described by Saidiya Hartman, by ensuring that her story—and by extension, the stories of many other black women—were heard, validated, and remembered (Hartman).

Conclusion

Although Black women have been instrumental in the evolution of rock and roll from its inception, their contributions are often overshadowed in a narrative that predominantly celebrates white male artists. Tina Turner stands out as a notable exception, enjoying widespread renown and name recognition that has endured into the twenty-first century. Through her dynamic performances, public disclosures, and literary contributions, Tina Turner actively challenged and addressed archival silences surrounding black femininity, glamour, sexuality, and gender-based violence, embodying a form of resistance that transcended the boundaries of entertainment to enact a profound political and cultural shift. Her career also demonstrates the significance of the physical body as a site of resistance, where movement, dress, and other forms of bodily expression become powerful tools for asserting autonomy and challenging the oppressive structures that perpetuate archival silences. Furthermore, her public archive demonstrates how the accumulation of individual acts of defiance can build up to more dramatic forms of resistance, contributing to larger-scale social change. Her engagement with the dynamics of race, gender, power, and access within the music industry was direct and transformative. This refusal to stay within the limited social space for black female performers allowed her to reshape the landscape of rock and roll as a means of liberatory politics (Maureen, 240). Her story challenges us to consider the power dynamics at play in the creation and preservation of history and to recognize the potential for individual narratives by and about Black women to fill the archival silences left by traditional historiography.

Works Cited

Note: For the bibliographies of the primary sources of this digital exhibit, click on the green link embedded in the title caption of each image to access its metadata page.

Botelho, Renan. “Tina Turner: Her Most Iconic Outfits Through the Decades.” Footwear News, 24 May 2023, footwearnews.com/gallery/tina-turner-best-looks-onstage-red-carpet-2018-grammys/ike-and-tina-travelling/.

Bushby, Helen. “How Tina Turner ‘broke the silence’ on domestic abuse.” BBC, 25 May 2023, www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-65673196.

CBS News. “From the Archives: Tina Turner's 1984 Interview with CBS News.” YouTube, uploaded by CBS News, 1984, www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9i6MhZaz7s.

Chisholm, Shirley. "The Black Woman in Contemporary America." Speech, University of Missouri, Kansas City, 17 June 1974. American RadioWorks, americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/blackspeech/schisholm.html.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe, vol. 12, no. 2, 2008, pp. 1-14. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/241115.

Kemp, Sam. “How Music Fuelled the Sexual Revolution.” Far Out Magazine, 23 June 2022, faroutmagazine.co.uk/music-fuelled-sexual-revolution-thurs/.

Leffler, Warren K. “Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.” Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, 28 Aug. 1963, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003654393/.

Mafe, Diana. “Rest in Power: Tina Turner—Queen of Rock & Roll, Acid Queen, Queen of Hearts.” Ms. Magazine, 30 May 2023, msmagazine.com/2023/05/30/remembering-tina-turner/.

Mahon, Maureen. Black Diamond Queens. Duke University Press, 2020.

Moore, Madison. “Tina Theory: Notes on Fierceness.” Journal of Popular Music Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, 2012, pp. 71–86.

Morrison, Toni. “What the Black Woman Thinks About Women's Lib.” The New York Times, 22 Aug. 1971, sec. SM, www.nytimes.com/1971/08/22/archives/what-the-black-woman-thinks-about-womens-lib-the-black-woman-and.html.

Myers, Marc. “Remembering Tina Turner, a Fierce and Seductive Rock and Soul-Music Icon.” The Wall Street Journal, 25 May 2023, www.wsj.com/articles/remembering-tina-turner-a-fierce-and-seductive-rock-and-soul-music-icon-2bc1d4ff.

O’Neil, Lorena. “Tina Turner Was Open about Her Abuse. Now, Her Legacy Is Saving Survivors.” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 26 May 2023, www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/tina-turner-ike-domestic-abuse-survivors-1234741396/.

Parker, Christopher. “Tina Turner, Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Left an Indelible Mark on Music History.” Smithsonian Magazine, 25 May 2023, smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/tina-turner-career-legacy-180982246/.

Périer, Marie. “Cher, Tina Turner or Beyoncé: Who Wore Bob Mackie’s Flame Dress Best?” Translated by Isabel Nield, Vogue France, 17 March 2018, www.vogue.fr/fashion/fashion-news/story/cher-tina-turner-or-beyonce-who-wore-bob-mackies-flame-dress-best/1543.

Royster, Francesca T. "Feeling like a woman, looking like a man, sounding like a no-no: Grace Jones and the performance of Strangé in the Post-Soul Moment." Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, vol. 19, no. 1, 2009, pp. 77-94, doi:10.1080/07407700802655570.

Turner, Tina. My Love Story. Atria Books, October 15, 2018.

“Tina Turner.” Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Library & Archives, 2021, library.rockhall.com/tina_turner.

Contact: Please feel free to reach out to me at neha.c.agarwal.24@dartmouth.edu with any questions/ comments/ thoughts. Thank you for visiting this digital exhibit!