Tiffany C

Introduction

This exhibit explores Black women and families’ experiences of kinship beyond Eurocentric and heteronormative ideals of the nuclear family during the postbellum period and the mid-20th century. From partus sequitur ventrem laws enforcing the heritability of slavery to seventeenth-century Virginia slave codes levying higher taxes on households with Black women, Atlantic slavery “relied on a reproductive logic that was inseparable from the explanatory power of race” (Morgan, 1). White slaveowners’ efforts to separate, delegitimize, and pathologize Black families intentionally coincided with the structural oppression that Black women faced under slavery because “[e]nslaved people had to be understood as…outside of the normal networks of family and community, to justify…mass enslavement” (Morgan, 1). As a result, White legislators often sought to assert control over Black families and kinship structures by regulating Black women’s identities as mothers and wives. Post-Emancipation, Black women continued to contend with cultural and political expectations of Black motherhood and conjugal relations in order to resist their continued structural oppression.

This exhibit will focus on the cultural and political reverberations of the Marriage Rules of the Freedmen’s Bureau during the Reconstruction Period and the policy recommendations of the Moynihan Report during the mid-20th Century to contextualize how Black women and Black families appropriated, subverted, rewrote, and refused their expected social roles to pursue freedom. By framing the survival strategies of Black families as intergenerational acts of resistance and love, the exhibit intentionally intervenes against past and present instantiations of the pathologizing rhetoric that targets Black women as political scapegoats for structural anti-Blackness and misogynoir.

The Reconstruction Era

The Freedmen's Bureau and the Marriage Plot

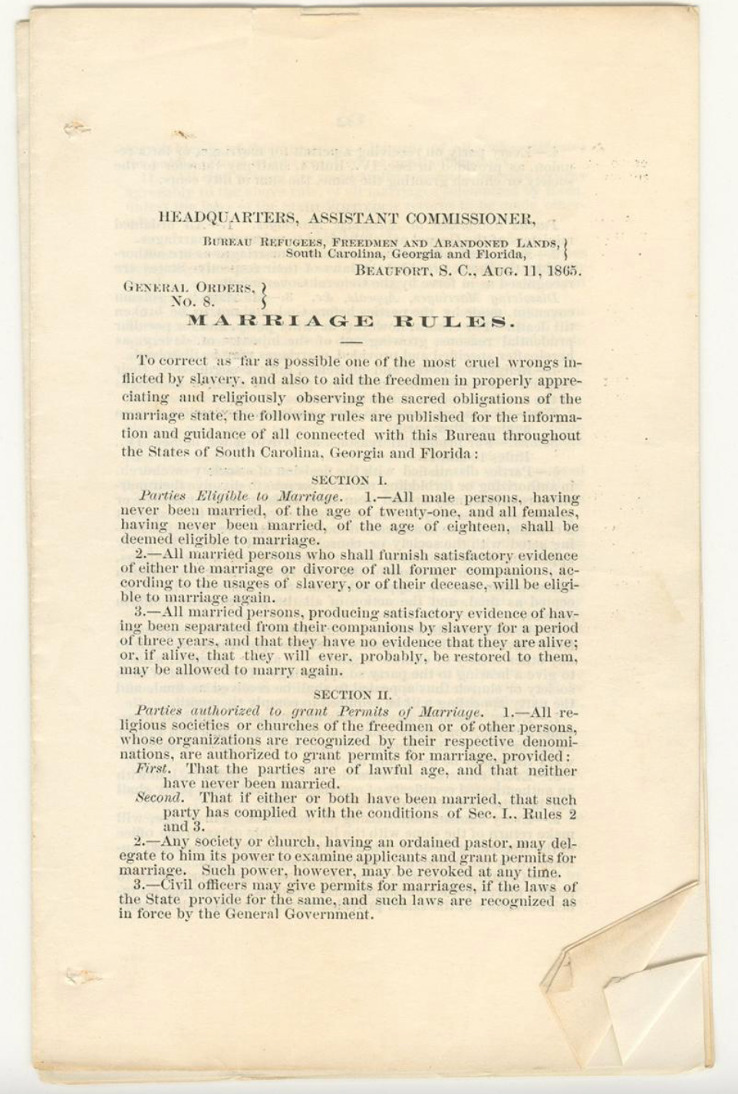

During Reconstruction, the Freedmen’s Bureau “intensified its role as marriage policymaker for ex-slaves” (Hunter, 238). The Freedmen’s Bureau was responsible for adjudicating conflicts between married couples (including domestic violence cases) and enforcing a “permanent, monogamous, exclusive” relationship where men were the household (Hunter, 233). Southern states worked with local officials to design legislation that punished men for not providing sufficiently for their families and women if they did not live up to their designated social roles as wives and mothers (Hunter, 234). Building upon social stigmas and stereotypes that formerly enslaved Black couples were more likely to have children out of wedlock, Freedmen’s Bureau Officials warned formerly enslaved Black women to “now that you are free, live as becomes a free Christian woman” and preserve modesty in all their sexual and romantic relations (Hunter, 236). The marriage rules that the Rufus Saxton, the assistant commissioner for South Carolina in 1865 issued for South Carolina, Florida, and Georgia explained the criteria for “former slave couples” to marry or remarry, and the responsibilities that husbands and wives had to each other and their children (Washington). The document’s statement that marriage was a religious sacrament (“religiously observing the sacred obligations of the marriage state”) and that marriage eligibility was conditioned upon never having been married before is representative of similar legislation around freedmen marriages nationwide (Washington).

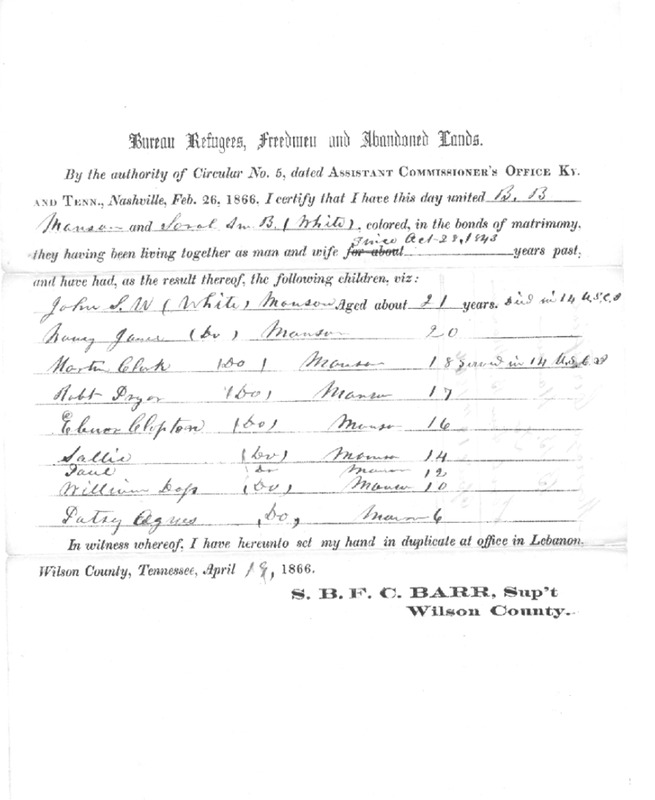

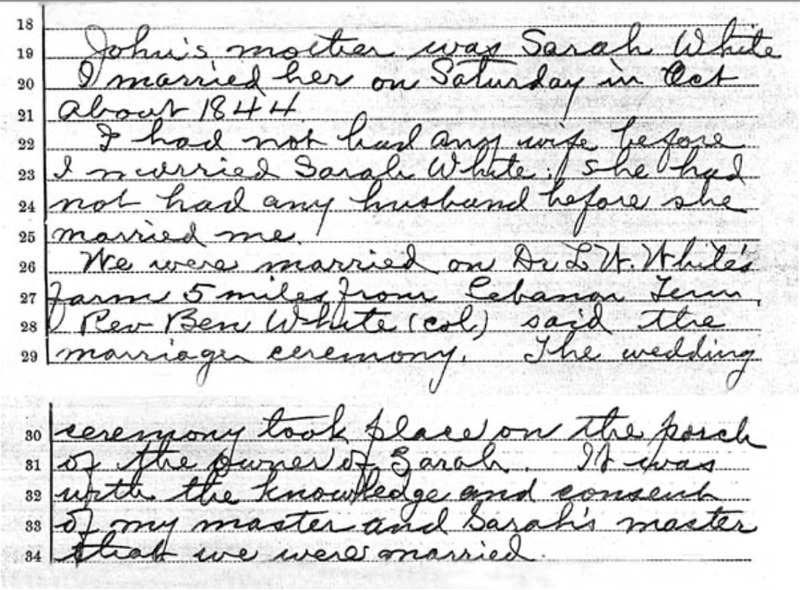

After the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau drew up over 10,000 marriage certificates for African American families. Beyond simply affirming romantic intimacy between husband-and-wife, these marriage certificates also legitimized “the offspring that resulted from them” (Hunter, 5). Indeed, this marriage certificate for the formerly enslaved couple Benjamin Berry Manson and Sarah Ann Benton White includes not only their names but the names of 9 out of their 16 children, ranging in age from 6 to 21 (Washington). Manson and White, who lived in Tennessee but on separate farms during slavery, had also been married in a “slave marriage” that was not recognized by the law but whose ceremony demonstrated how their relationship extended beyond the date of their marriage certificate (Washington). Their prior wedding is attested in an interview with Manson in his pension file (he filed it on behalf of his son John, who served in the “14thRegiment of the United States Colored Troops” (Washington). Manson and Sarah were married by a Black preacher named Rev. Ben White with the approval of White slaveowner Joseph L. Manson (Washington). Both marriage records demonstrate how marriage represented Black people’s commitment to keeping their families together. Black women were coerced into reproductive labor that “helped forge the nation’s wealth,” and their bodies were stigmatized by “tithable labor laws” which “created obstacles for free blacks to marry” by taxing households with Black women at higher rates (Hunter 4; Hunter, 9). The marriage between Manson and White demonstrates how free Black families had to continue asserting their right to exist and evolve alongside the legislative systems which served to delegitimize their kinship.

Information Wanted: The Challenges & Triumphs of Reuniting with Family After Slavery and the Civil War

From 1863 to the early 20th century, many formerly enslaved Black people who were separated from their loved ones by slavery and the Civil War placed “Information Wanted” ads in newspapers in hopes of reuniting with them (Shapiro and Pao). Because many Black people were separated by their families when they were sold to different plantation owners, geographic distance proved a major barrier to reunion efforts (Williams, 143). Although Congress had just established the Freedmen’s Bureau for the purported purpose of helping to manage affairs for freedmen and freedwomen, racist Bureau officials often rejected requests for financial assistance with transportation for reunited families, with one stating: “It seemed to me that if the N*groes wanted to travel they should not insist on doing it at the expense of the nation, but should earn money and pay their own fare like white people” (Williams, 146-147; asterisk mine). Regardless, many Black people took transportation into their own hands, sometimes walking hundreds of miles to where their loved ones were last seen (Williams, 144).

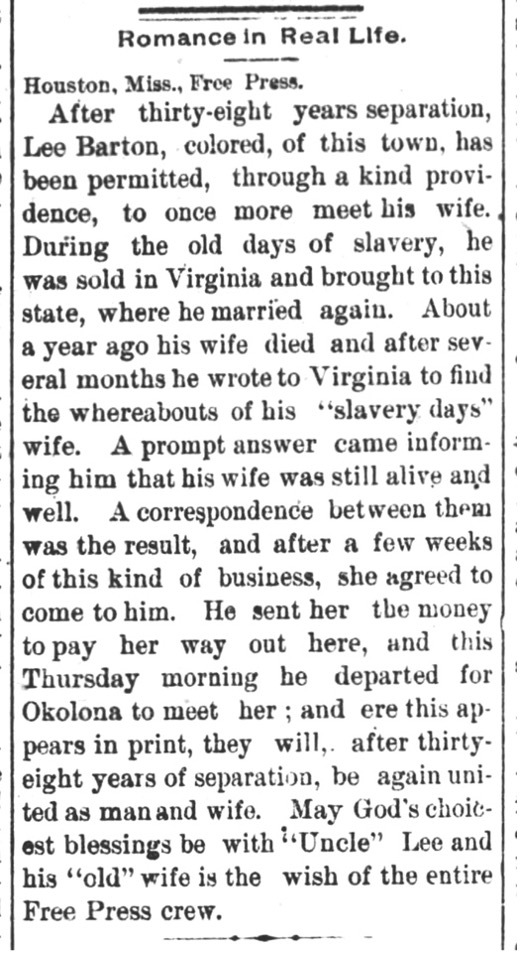

Another barrier to unification was the difficulty of locating loved ones whose names may have changed as a result of changing owners, marriage, or adopting a new name after escaping slavery (Williams, 143). As a result, many Black people turned to community networks within Black churches (or newspapers run by Black churches such as the Christian Reporter) or invested their hard-earned wages from their jobs as field hands or domestic workers to place ads in local newspapers soliciting information (Williams, 153-154). While some of these ads ran for months without securing results, others were successful in reuniting with their loved ones and published news of their reunions in the newspapers to provide hope to other families that their efforts would succeed (Williams, 168). In this newspaper ad from Alabama’s Eufala Daily, a pen-pal romance is described between Lee Barton and his former wife. Although their re-marriage may not have been conventional given Christian social stigmas against divorce, the newspaper presents their reunion as a triumph of love after 38 years.

Of White Wedding Dresses and Pension Files: Re-Ritualizing and Re-Commemorating Black Love After Emancipation

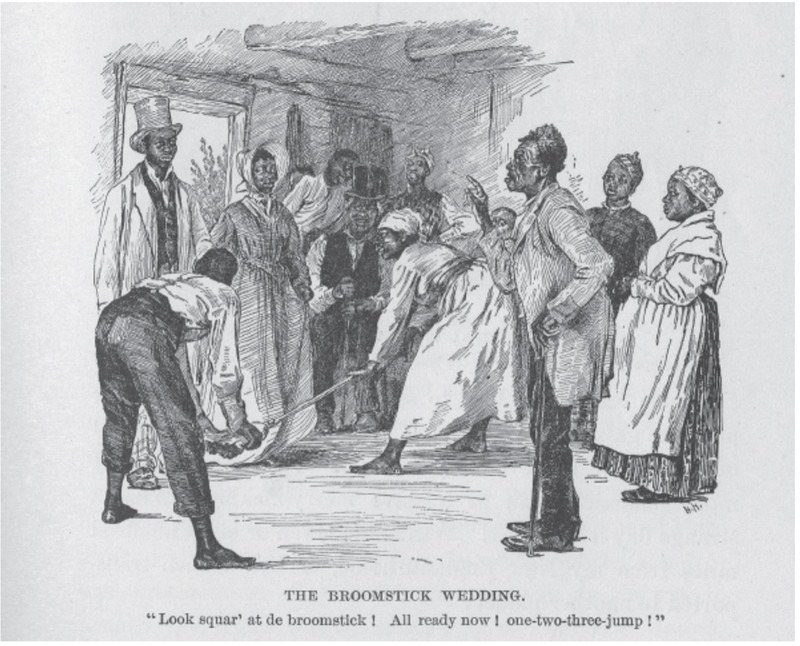

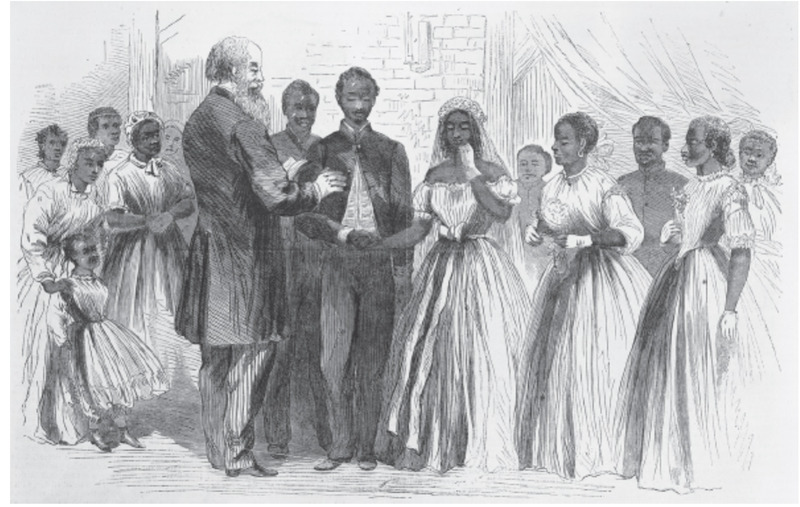

During slavery, enslaved people often did not have any say in their marital relations, which were usually imposed upon them by White slave owners and staged as a spectacle for White entertainment (Stevenson, 35). One such marital ritual that White people imposed upon the Black people they enslaved was “jumping the broom,” in which a couple would jump over a broom together in front of White slaveowners in order to finalize their marriage ritual (Stevenson, 35). After the Civil War, Black people created and extended traditional Christian and White wedding rituals for their own communities that rejected the imposition of negative stereotypes on their love as immodest and deviant. Willis Dukes stated, “We didn’t jump over no broom neither. We was married like white folks wid flowers and cake and everything” (Stevenson, 40). For brides, the wedding dress was particularly important, with a white dress and white veil holding special significance. Molly Horn from Arkansas shared, “Mama bought me a pure white veil. I was dressed all in white” (Stevenson, 7). Brides that could not afford a traditional white dress created beautiful alternatives such as blue dresses (“blue for true”) and dresses made of dainty calico or even black silk (Stevenson, 7). In some instances, White former slaveowners would help defray the costs associated with the wedding or lend their own clothing – though this “assistance” was not for charitable motives but rather to continue exerting financial control over Black families (Stevenson, 9). Despite the logistical challenges of organizing a reception, party, feast, and wedding attire for their loved ones, however, such weddings were a testament to and commemoration of freedom for Black families and couples.

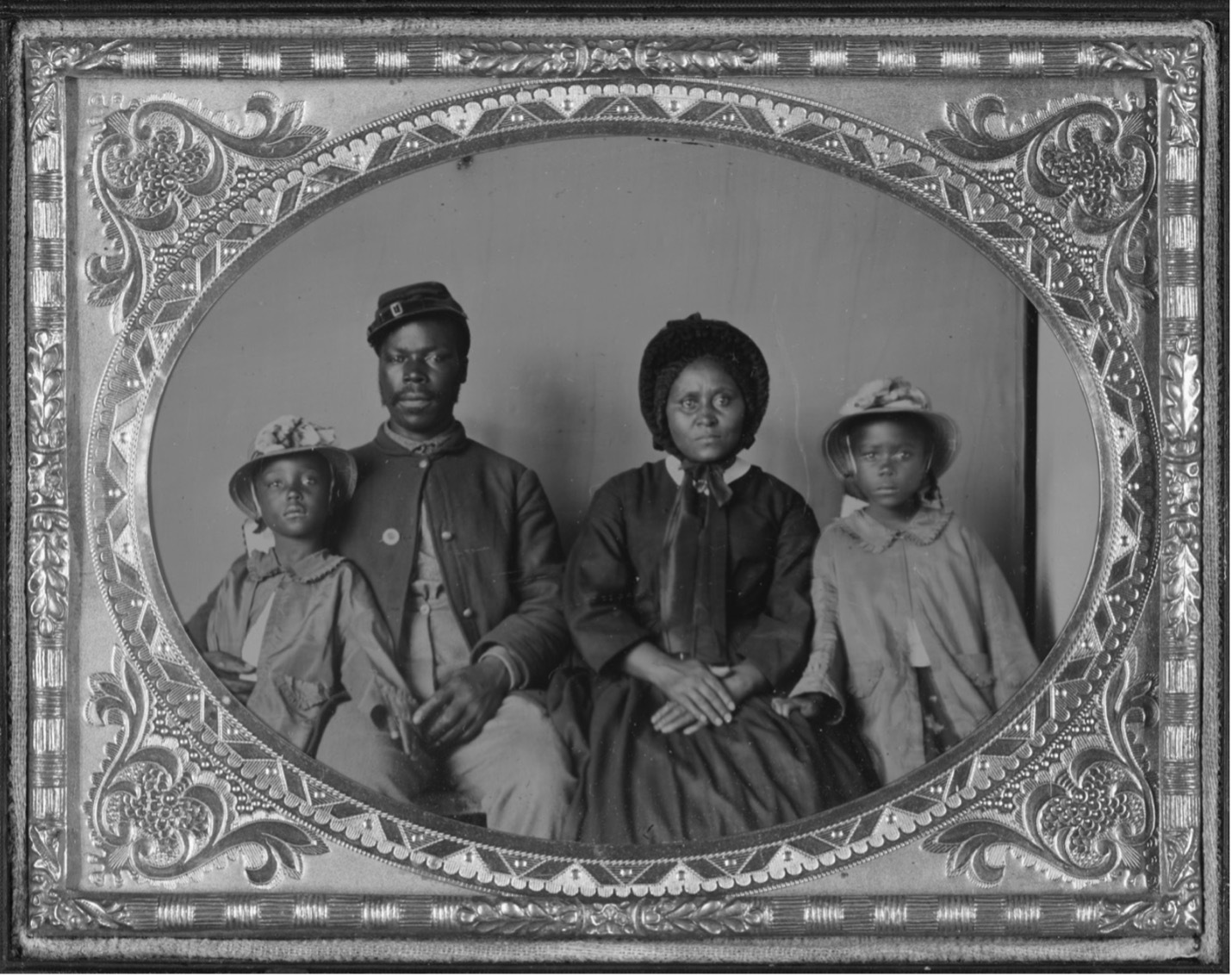

During the Civil War, Black soldiers also memorialized their families and loved ones through photography. This family portrait of Sergeant Samuel Smith of the “United States Colored Infantry 119, Company D,” his wife Mollie, and daughters Mary and Maggie, would have been considered a luxury costing around $0.25 to $2.50 (the equivalent of approximately $6 to $60 in the current day) (Hunter, 1977; Willis, 10). Many soldiers also developed smaller pocket-sized “tintype” images that could be developed instantly, so they could carry pictures of their loved ones with them on the battlefield (Willis). After the Civil War, Black women who reunited with husbands who had served in all-Black regiments in the Union Army were eligible for widows’ pensions (Frankel). In practice, obtaining such pensions proved difficult, as couples that had been married during slavery would not have had legally ratified documents of their marriage (Frankel). The pension records that widows filed included a plethora of documents attesting to their kinship with their husbands, including oral testimonies speaking of their experiences as domestic workers and field hands, relationships with their neighbors, marriage certificates filed with the Freedmen’s’ Bureau, and memories of wedding ceremonies both during and after slavery (Frankel). Black women were therefore often legal guardians and financial stewards of their husbands’ legacies of military service in the Union.

The Twentieth Century (1906 - 1979)

“A whole world could be made and undone by a row of figures and the future eclipsed by ratios or the lines of a flowchart. The table of unions created, severed, and thwarted was a historical epic of love and trouble, a long chronicle of violation and unwanted touch."

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, 122.

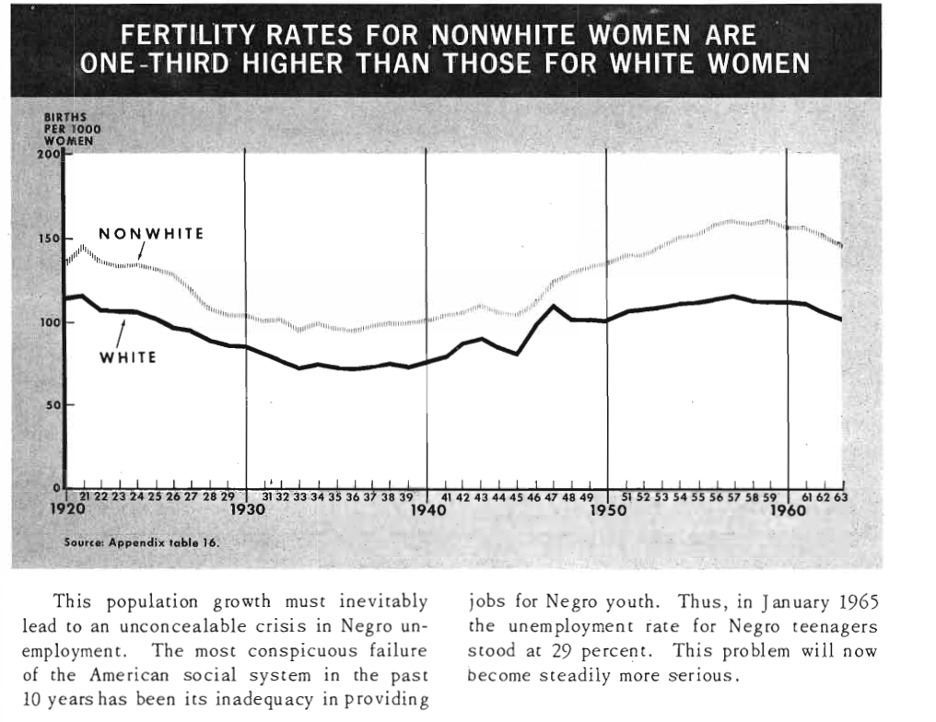

Black women’s struggles against White policymakers who sought to pathologize their diverse kinship structures as deviant and lawless, deny them access to resources they were entitled to, and weaponize the violence of the state against them did not end after Reconstruction. Rather, the social stigmas against Black women’s conjugal and sexual relations anchored themselves in new social policy that sought to continue their sexual and social exploitation. In this section of the exhibit, we will explore the ongoing legacies of the Freedmen’s Bureau through contextualizing diverse Black feminist responses to the Moynihan Report of 1965 during and after the Civil Rights Movement. This exhibit frames the Moynihan Report through Saidiya Hartman’s concept of the “afterlife of slavery,” which refers to Black people’s “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment” caused by “a racial calculus and a political arithmetic…entrenched centuries ago” that continues to endanger Black lives (Hartman, “Lose Your Mother,” 6). Although the struggles that Black women faced during the Antebellum Period were distinct from those of the mid to late 20th century, closely reading the social rhetoric of both periods enables students to interrogate the origins and material implications of harmful social scripts that continue to be repurposed today – as well as better inform their understanding of Black women’s liberation strategies as intergenerational creative projects.

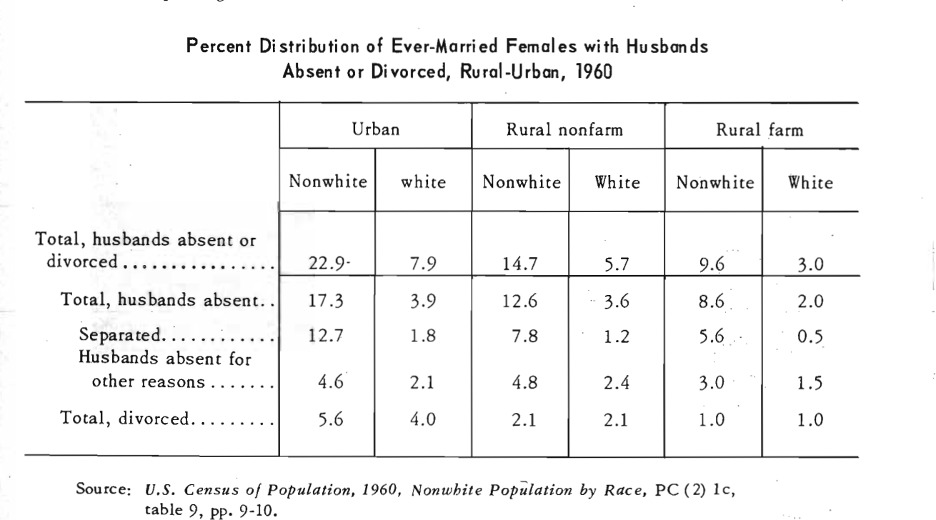

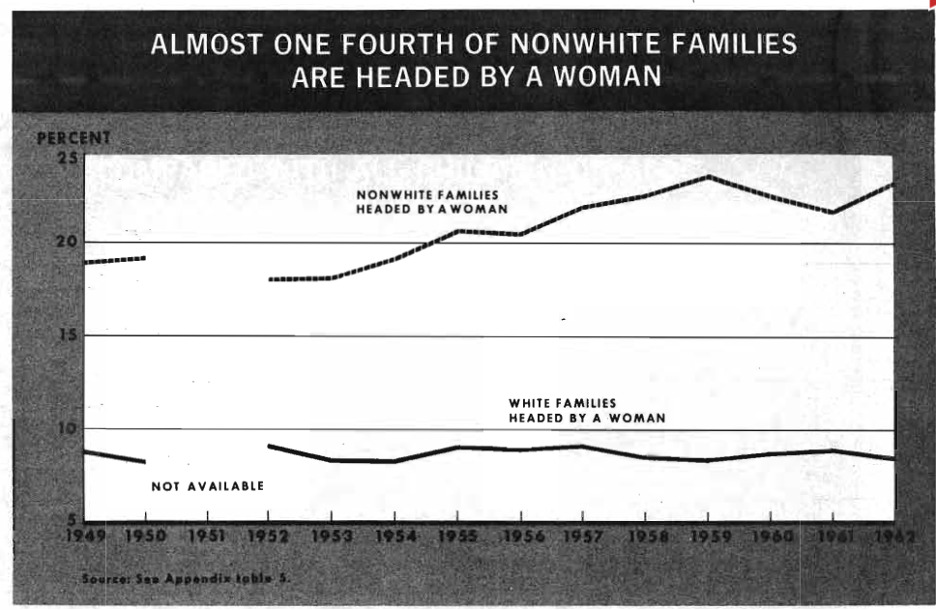

Daniel Patrick Moynihan published “The N*gro Family: The Case for National Action” (asterisk mine) during his time as a member of the Johnson administration (Geary, 3). In what later became colloquially known as the Moynihan Report, Moynihan argued that “female-headed families” were responsible for the failure of civil rights legislation to address economic inequality between Black and White Americans (Geary, 1-2). Black feminists of the past and present have heavily critiqued this report for pathologizing Black families as deviant and Black women in particular as culpable for the economic and social disenfranchisement that Black Americans experience.

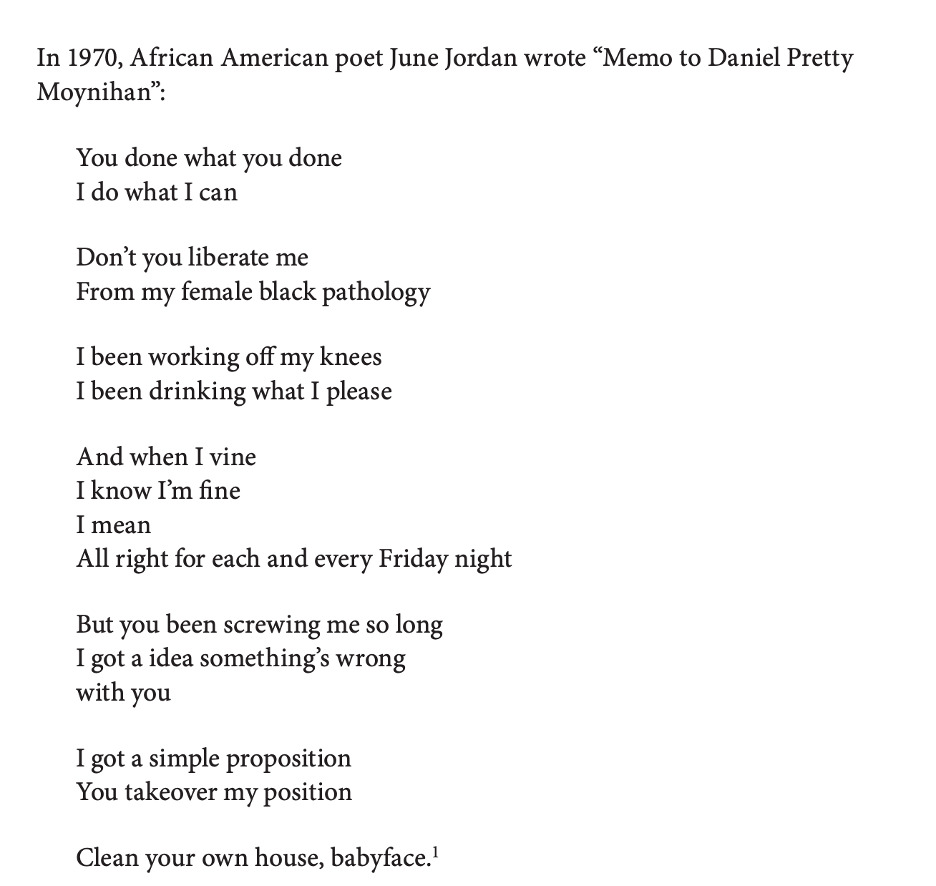

Hortense Spillers quotes a specific line from the report, which states “In essence, the N*gro community has been forced into a matriarchal structure which, because it is so far out of line with the rest of American society, seriously r*tards the progress of the group as a whole, and imposes a crushing burden on the N*gro male and, in consequence, on a great many N*gro women as well,” to explore how long-standing stereotypes about Black women’s “‘dominance’ and ‘strength’ come to be interpreted by later generations – both black and white, oddly enough – as a ‘pathology,’ as an instrument of castration” (Moynihan 75, as quoted in Spillers 65; Spillers 74, asterisks mine). Such concerns were subsequently addressed and refuted by Black feminist poets such as June Jordan as well as Black feminist organizers working with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA) (Geary, 155)

Historical Context

Even prior to the publication of the Moynihan Report, Black women sex workers received the brunt of societal blame for the perceived moral degradation of Black American communities. They were the frequent target of police raids on prostitution in Black neighborhoods such as Philadelphia’s 7th Ward during the early to mid-20th century (Hartman 107). A Philadelphia Inquirer article reported on one particularly large raid of 48 prostitutes, stating that the raid in “Little Africa netted a courtroom full of women of all shades, from inky black to gold, all young, all tough, and all given to swagger and vile oaths” (Inquirer, quoted in Hartman, 116). White feminist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman blamed “cheap women” in the city for “troubl[ing] the marriage plot and produc[ing] nameless children” (Hartman, 117). Young sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois included Black women who were prostitutes in “Grade Four” of his typology of the Black population of Philadelphia, among “the lowest class of criminals…and loafers, the submerged tenth” (Hartman, 131). While many Black women who worked as prostitutes preferred to keep their identities secret, Madame Sperber, who owned a brothel in Junction City, Kansas, employed photographer Pennell to make studio portraits of herself, the women she employed, and her husband (Bromberg). It is likely that these photographs were used for advertising (Pennell was largely a commercial photographer) (Shortridge and Pennell, 81)). The women in the photograph are dressed in “Mother Hubbard” dresses which was popular among prostitutes of the time (Bromberg). The varying modes of dress among the women illustrates the power dynamics even among Black women sex workers.

Black Feminism and a New Politics of Sexuality: Responses to Moynihan and Misogynoir *

*Misogynoir was a term coined by Dr. Moya Bailey in 2008 to "describe the anti-Black racist misogyny that Black women experience, particularly in US visual and digital culture" (Bailey, 1).

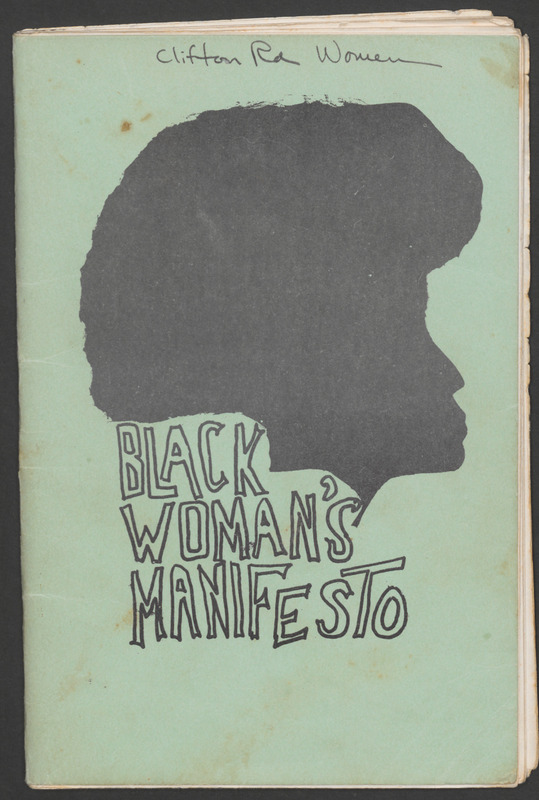

“The black woman is demanding a new set of female definitions and a recognition of herself as a citizen, companion, and confi- dant, not a matriarchal villain or a step stool baby-maker."

Black Woman's Manifesto, 12

The TWWA was founded by Black women such as Fran Beal, Mae Jackson, and Gwen Patton, among others, who were active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the Civil Rights Movement. The SNCC gained national prominence through their freedom rides program for Black voters (Romney and Fernández, 44). In 1964, Black and White women staffers at the SNCC protested the gendered roles they played in the organization (taking meeting minutes, not being able to participate in the most important committees, and being excluded from leadership consideration) (Romney and Fernández, 46). Patton stated in an interview of working with James Forman (SNCC’s executive secretary), “Why do you have these young girls running around doing the brothers’ bidding?” (Romney and Fernández, 47).

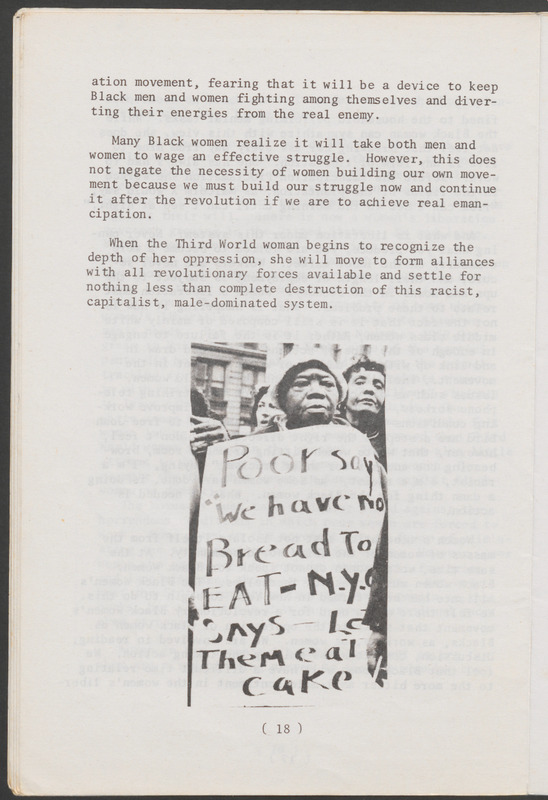

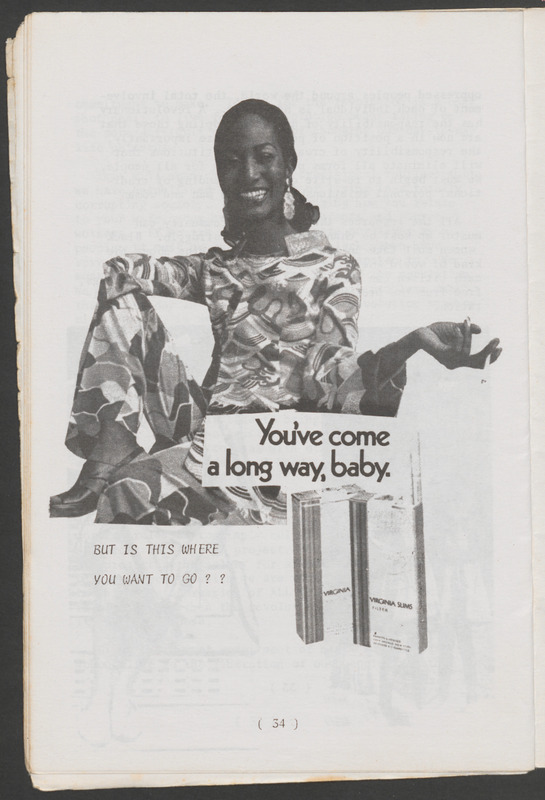

Black women continued to discuss their concerns with each other and formed a Black Women’s Caucus (SNCC’s BWLC) in 1969. They were concerned with Moynihan’s idea of the “black matriarchy” because many felt that Moynihan was blaming Black women, racism’s primary victims, for racism (Romney and Fernández, 50). Questions raised at their first meeting included, “Is a black woman different from a white woman? Are babies problems? Does capitalism say babies are problems? Can you organize for the revolution if you have children?” (Romney and Fernández, 54). Because “the mimeograph was said to be the favorite weapon of the left,” Black women involved in the BWLC, including author Toni Cade Bambara and lawyer Eleanor Holmes Norton wrote a publication called Black Woman’s Manifesto that raised consciousness of Black women’s issues (Romney and Fernández, 55). Fran Beal’s article “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female” in the Black Woman’s Manifesto is a pioneering text in intersectional feminist thought, in which she identifies capitalism as a key source of “racism and male chauvinism” (Romney and Fernández, 56). Rather than taking a separatist stance, however, Beal explained how acknowledging the oppression that Black men faced did not justify using Black women as the “scapegoat for the evils that this horrendous system has perpetrated on Black men” (Romney and Fernández, 56). This manifesto was the basis by which the BWLC evolved in an autonomous collective called the Black Women’s Alliance.

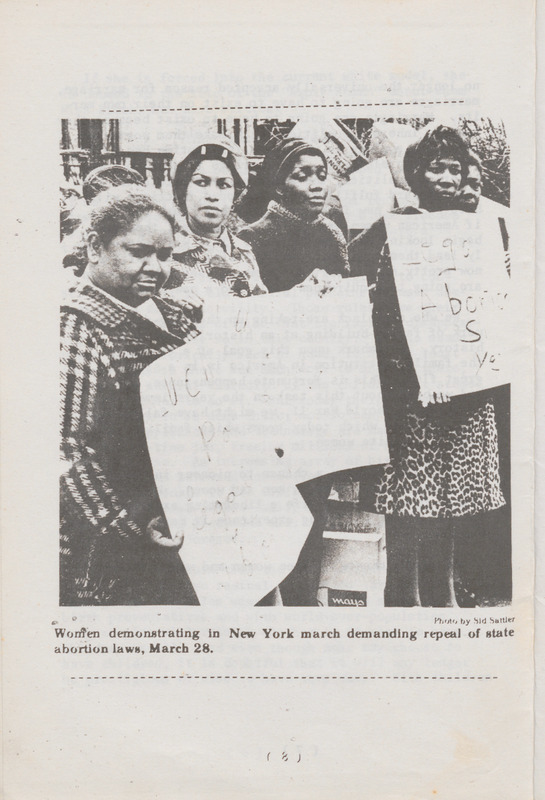

In Double Jeopardy, Beal also pointed out connections between the medical abuses that Black women in the United States and women in India and Puerto Rico faced: regimes of forced sterilization, unsafe and often deadly abortion practices, and nonconsensual testing of birth control pills. In 1970, extending Beal’s conceptualization of interconnected struggles between women of color, the Black Women’s Alliance became the Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA) (Romney and Fernández, 60). Yemaya shared, “TWWA was all about inclusion. We stood for women of color supporting each other regardless of sexual orientation, religious belief, or cultural differences. This was a revolutionary line of thought in the seventies. It was transcending. We knew as we defined ourselves first as the Black Women’s Alliance it was important to broaden our vision if we were to project lasting change” (Romney and Fernández, 59). They published a new manifesto in 1971, this time called Triple Jeopardy (in reference to Double Jeopardy) and expanded their political advocacy to anti-imperialist causes from Palestine to Cuba (Romney and Fernández, 70).

“I personally do not need any of these supersophisticated charts and magical graphs to tell me my own momma done better than she could and my momma's momma, she done better than I could. And everybody's momma done better than anybody had any right to expect she would. And that's the truth!...So, Im' asking you real nice: Don't you talk about my momma."

June Jordan, "Don't You Talk About my Momma," 80

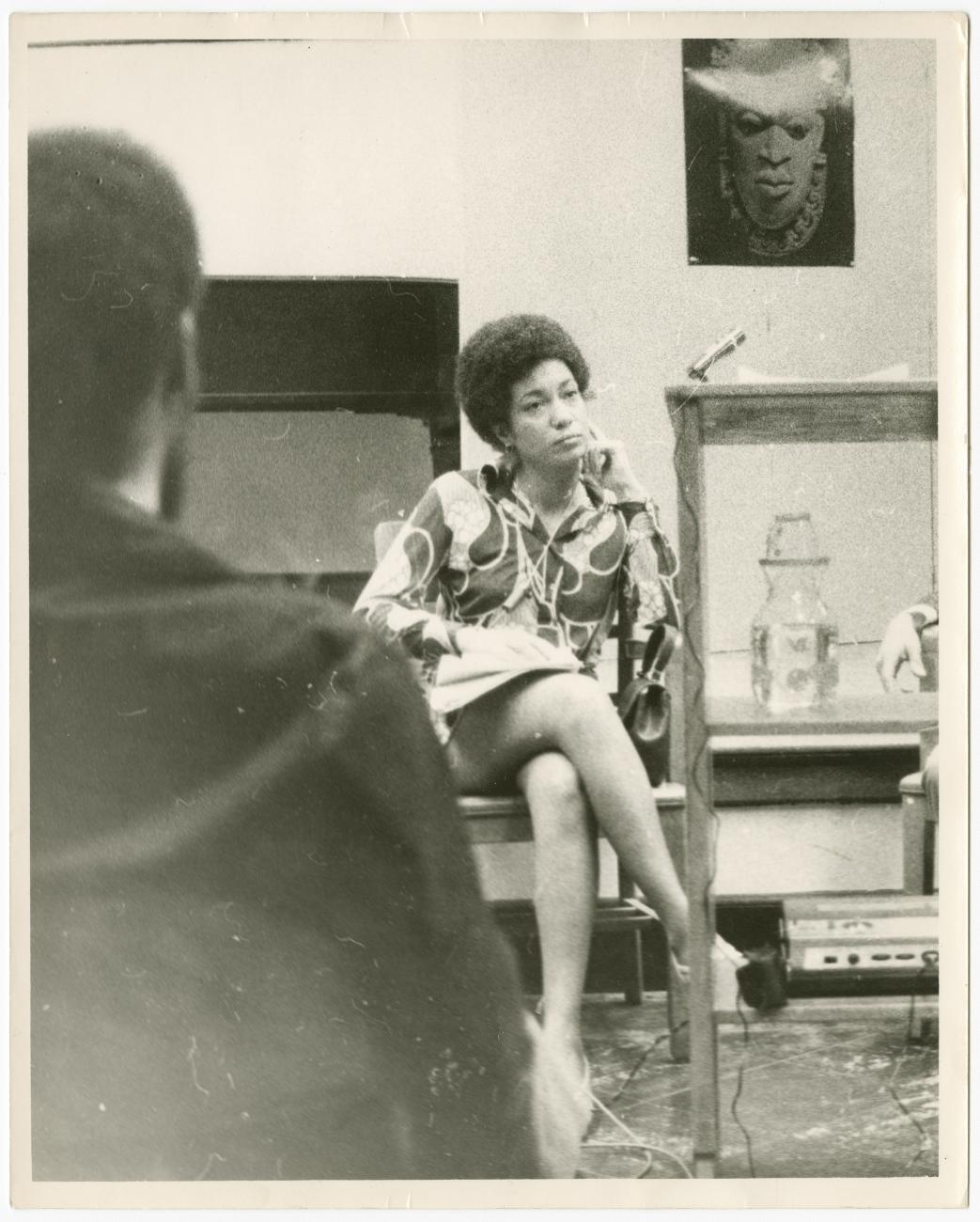

June Jordan, a bisexual Black feminist writer and professor, wrote back against the Moynihan report and continued combatting the pathologization of Black mothers and of Black and Queer communities throughout her life. Jordan reflected, “Back in 1965, Daniel P. Moynihan issued a broadside insult to the National Black Community…with the theory that we, Blackfolks, and that we, Black women, in particular, constituted ‘the problem’” (Jordan, "Don't You Talk," 3). She recounts her motivation for writing the poem: “That’s all he deserved, as I saw it. I couldn’t take him seriously, and certainly not to my heart! Plus, I didn’t have the time for Mr. Moynihan or any other Mr. Man’s theories about me…I had to no time to waste” (Jordan, "Don't You Talk," 4). June Jordan’s defended the diversity of life within Black families and their survival strategies that did more than the White House ever could: “our families might have adult women and children, and no adult men, or our families might have on white parent and one Black parent, and their children, or our families might have three generations living in two rooms…the majority did have, a Black father and a Black mother and their children, but, regardless, we were all there, for each other” (Jordan, "Don't You Talk," 65).

Jordan's respect for the diversity of Black kinship structures established the basis for her new politics of sexuality that she articulated in a 1991 speech to Stanford students. Jordan shared that “Freedom is indivisible, and either we are working for freedom or you are working for the sake of your self-interests and I am working for mine” (Jordan, "A New Politics," 439). Jordan continues, “This is a New Politics of Sexuality…I will call you my sister, on the basis of what you do for justice, what you do for equality, what you do for freedom and not on the basis of you who are, even so I look with admiration and respect upon the new, bisexual politics of sexuality" (Jordan, "A New Politics," 441).

Jordan’s intergenerational advocacy and her lived experiences as both a Black mother and a bisexual woman demonstrate how Black women used the vocabulary of intersectionality to create new avenues of freedom in the past, present, and future.

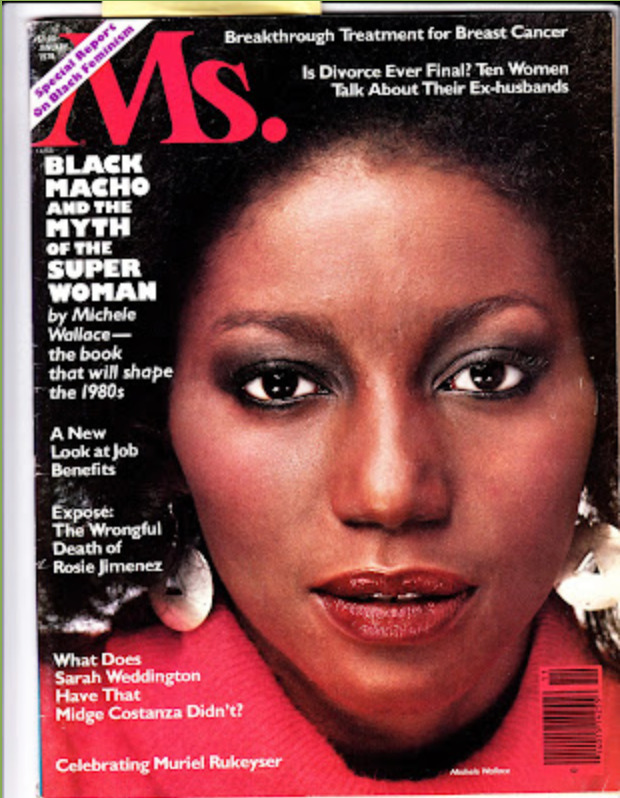

In 1979, 27-year-old Michele Wallace wrote Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, which critiqued the Moynihan report for reviving “the notion that African American women were powerful ‘matriarchs’ who held disproportionate authority in their families and communities” (Geary, 154). Wallace wrote that the report incited Black men to be hostile against Black women and believed that the ideal of the “Black Macho” was hindering the Black liberation movements in America (Geary, 155). Ms. Magazine offered to publish an excerpt of Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman for their 1979 issue and to feature Wallace on the cover (Geary, 154).

In a 2009 blog post reflecting on the issue, Wallace wrote that “At the shoot, instruction one. Take those braids out of your hair. They will ruin the cover. This the hairdresser did. But I didn't know what to do with my hair under such circumstances so you see instead that unruly hair style I had where my hair is being I am not sure what. If it looks like my face is covered with makeup, it is, as the makeup artist applied layer after layer of a various assortment of foundations trying, I can see now, to somehow brighten my hopelessly olive blackness. People say this is a beautiful picture but I can't see it. I hated it" (Wallace).

Wallace’s experience navigating White feminist spaces to platform her criticisms of gender relations within Black liberation movements proved polarizing, then and now. At the time, Wallace received criticism from Black men writers, who thought that “women had fallen pretty to white feminist propaganda,” mainstream outlets such as The New York Times for “vast generalizations and…devaluing the success of the Civil Rights movement,” and Black feminist intellectual and activist June Jordan, who questioned Wallace’s decision to not conduct interviews with members of the Black Power movement, rely upon White historians’ accounts instead, and elide analyses of contributions from Black Women such as Francis M. Beal to combat sexism in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNNCC) (Hernton as quoted in Ms. Magazine; Ms. Magazine; Jordan, "To Be Black and Female").

Wallace later reflected on Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, believing that while it may have not always found its intended audience, she believed that it was destined to “find its home” in the future and that “perhaps it will just help make the future. Just because I gave it birth, doesn’t mean I understand it" (Wallace).

A Note of Thanks

Thank you for visiting this digital exhibit! I hope that it was as thought provoking and engaging for you to read through as it was for me to research and curate. I would like to especially thank Professor Sinclair for her invaluable help and guidance, as well as my fellow classmates for a great term and for many insightful class discussions. Please feel free to reach out to tiffany.h.chang.23@dartmouth.edu with any feedback or questions.

Works Cited

Note: For bibliographic information on the primary sources of this digital exhibit, please click on the green link embedded in the title caption of each image to access its metadata page.

Bailey, Moya. "Introduction: What Is Misogynoir?" In Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance, 1-34. New York, USA: New York University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479803392.003.0004

Bromberg, Nancy. “Loss of Vision: How Early 20th century Photograph Was Misjudged by Critics and How Archives Obscure the Image.” Medium. exposure magazine, June 25, 2018. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://medium.com/exposure-magazine/loss-of-vision-ebf2339713c2

Frankel, Noralee. “From Slave Women to Free Women: The National Archives and Black Women’s History in the Civil War Era.” Prologue Magazine, National Archives and Records Administration, Summer 1997. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/summer/slave-women.

Geary, Daniel. Beyond civil rights: The Moynihan Report and its legacy. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Hartman, Saidiya. Lose your mother: A journey along the Atlantic slave route. Macmillan, 2008.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments : Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. First edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Heather Andrea Williams. 2012. Help Me to Find My People : The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery. The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=422061&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Hunter, Tera W. Bound in wedlock: Slave and free black marriage in the nineteenth century. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Jordan, June. "A new politics of sexuality." Transformations. Routledge, 2015.

Jordan, June. “Don’t You Talk About My Momma!” In Technical Difficulties: African-American Notes on the State of the Union, 65–80. New York: Pantheon, 1992.

Jordan, June. “To Be Black and Female.” The New York Times, March 18, 1979, sec. BR. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/1979/03/18/archives/to-be-black-and-female-black.html

Morgan, Jennifer, “Partus sequitur ventrem: Law, Race, and Reproduction in Colonial Slavery.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 22, no. 1 (2018): 1-17.

Ms. Magazine. “Black History Month: The Myth of the Black Superwoman, Revisited.” Ms. Magazine. February 16, 2011. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://msmagazine.com/2011/02/16/black-history-month-the-myth-of-the-black-superwoman-revisited/

Norton, Eleanor Holmes, Maxine Williams, Frances Beal, and Linda La Rue. “Black Woman’s Manifesto.” Third World Women’s Alliance, 1975 1970. Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA) Archives, circa 1972-1994.

Romney, Patricia. We Were There: The Third World Women's Alliance and the Second Wave. Feminist Press at CUNY, 2021.

Shapiro, Ari, and Maureen Pao. “After Slavery, Searching for Loved Ones in Wanted Ads.” Codeswitch, National Public Radio, February 22, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/02/22/516651689/after-slavery-searching-for-loved-ones-in-wanted-ads.

Shortridge, James R., and Joseph Judd Pennell. Our Town on the Plains : J.J. Pennell’s Photographs of Junction City, Kansas, 1893-1922. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

Spillers, Hortense J. "Mama's baby, papa's maybe: An American grammar book." In The transgender studies reader remix, pp. 93-104. Routledge, 2022.

Stevenson, Brenda, “‘Us never had no big funerals or weddin’s on de place’: Ritualizing Black Family in the Wake of Freedom,” in Beyond Freedom: Disrupting the History of Emancipation, ed. David W. Blight and Jim Downs, 34-47. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Wallace, Michele. “Photo Essay: Black Macho and The Myth of The Superwoman 1970s.” Soul Pictures: Black Feminist Generations (blog), 2009. https://mjsoulpictures.blogspot.com/2009/08/black-macho-and-myth-of-superwoman.html.

Washington, Reginald. “Sealing the Sacred Bonds of Holy Matrimony.” Prologue Magazine, National Archives and Records Administration, Spring 2005. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/spring/freedman-marriage-recs.html.

Willis, Deborah. The Black Civil War Soldier : A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship. New York: New York University Press, 2021.