Zoe D

Black Female Author’s and the Subject of Enslaved Mothers Killing their Children

Most women are told that motherhood should be the happiest period of their lives. They should feel hope for their children and pride in their bright future. However, enslaved motherhood was more often full of fear, abuse, anxiety and separation, if those who carried children were able to be with them at all. Some women shielded their children, others simply lived for their own survival, but some committed acts that at face value feel unthinkable – they killed their own children or those in their care. Infanticide, which like Wattley defined as “not just… the killing of a baby or very young child, but to the killing of minors” (47), and purposeful abortions, were complex acts of resistance to the slave trade, merciful acts of protection from their inevitable fate, and responses to the brutal sexual abuses and forced breeding by masters. While these acts are chilling and heartbreaking, they were an important aspect of many female slaves experiences that many abolitionists and later historians have absconded to a part of political arguments on slavery. However, Black female writers of the Atlantic World have preserved not just the act of infanticide but their contexts, fallouts, and meanings in the lives of Black communities in a variety of forms and for a variety of reasons. Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Shirley Graham Du Bois’ It’s Morning, and Évelyne Trouillot’s The Infamous Rosalie all illustrate the tales beyond just women who committed infanticide because of slavery, but real lives shaped and altered by a system that led up to that decision and work together to preserve this important piece of Black women’s work towards freedom and inspire others to center their works on Black women’s lives and experience.

Infanticide has been practiced in a variety of cultures throughout the history of humanity including multiple indigenous cultures of the Americas and many African nations (Turner, 61-63). When Europeans encountered it among people they were colonizing, they associated it with a savagery due to not being Christian and bearing Eve’s biblical painful birth which would inspire empathy toward a child (Turner, 61-63). It became a part of the justification for the practice of enslavement as a form of civilizing Indigenous peoples and then Africans (Turner, 61-63). As colonialism and the slave trade expanded and infanticide by slaves was treated as a matter of financial cost to slave holders (Morgan, 178) because slave women’s children were slaves under multiple colonial laws including Haiti’s “Code Noir” and Virginia’s “Partus Sequitur Ventrum”. Pronatalist policies and the banning of slave imports throughout the Atlantic heightened the focus on enslaved women’s reproduction both for pregnant slaves and for their caretakers, enslaved midwives (Bush 195; Weaver 455-458). Knowledge of female anatomy and childbirth rested primarily in midwives who were valued as slaves for their abilities while heavily scrutinized in some instances when newborns died, however, their position uniquely allowed some of them to commit infanticide as a form of resistance to bringing new lives to the world to be enslaved or helped cover up mother’s acts of infanticide when asked to testify to a birth (Turner 1-3; Weaver 455-458; Eddins 141-145). As calls for abolition grew in the nineteenth century, infanticide became a consequence of slavery, with abolitionists publicly commenting on cases to argue that slavery’s brutality was the cause, so ending slavery would end infanticide (Turner 69). In the minds of white people, infanticide was an act of desperation, an act of savagery, but never an act of humanity, which is what the following Black female writers begin to draw out for their audiences.

Arguably her most famous book, Beloved is Toni Morrison’s fifth novel written in 1987 for not only the 40-60 year old suburban reader but the rise of black and white female audiences (PBS NewsHour, 9:34-10:52). The novel surround’s a former slave in 1873 Cincinnati named Sethe who, in 1856, escaped slavery after horrific abuse but was found by her former owner and rather than surrender kills her 2-year-old daughter and attempts to kill her two toddler sons, newborn daughter and herself (Morrison). Her owner decides they are tarnished and leaves them in Ohio, where 18 years later she and the now 18-year-old Denver are haunted by the dead baby’s ghost who turns up in the flesh as a 20-year-old Beloved, the name on her tombstone, to seek vengeance on a guilty, but not shameful or regretful Sethe (Morrison). The story also includes two other women who commit forms of infanticide. Sethe’s mother threw away all of her children, born from rapes by white men, except Sethe who she presumably tried to abandon when she attempted to escape and was hanged (Morrison 74, 240). A member of the Underground Railroad in the community named Ella who refused to nurse her baby after being a sex slave to a father and son for a year (Morrison 305). While Sethe judges her mother and Ella judges Sethe both indicate that they can understand the other woman’s actions, and while Sethe is apologetic toward Beloved she doesn’t regret her decision because “if I hadn’t killed her she would have died [from slavery] and that is something I could not bear to happen to her” (Morrison 236). For Denver, this creates a life of fear of her only caregiver and isolation until she has to mature and enter the community for Sethe’s survival (Morrison 242).

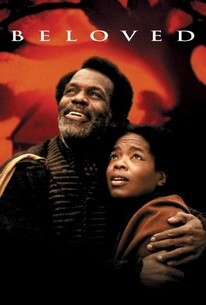

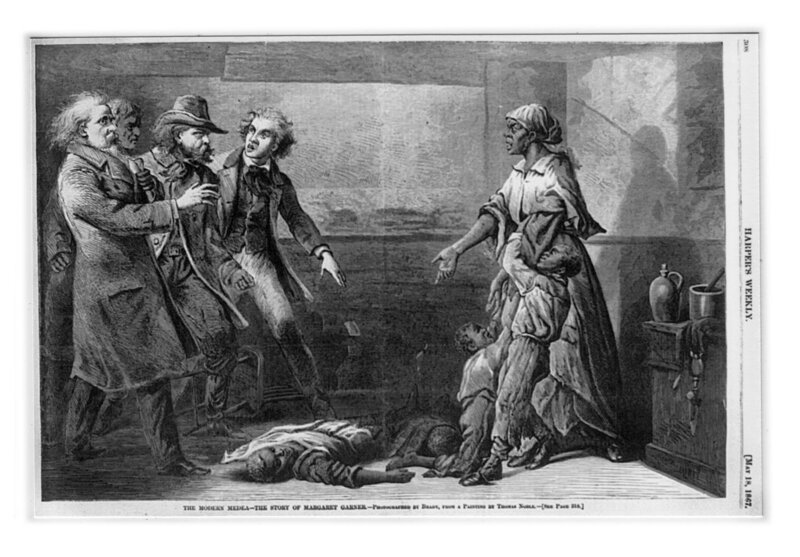

For her work, Morrison won a Pulitzer, but her goal was never to take home awards but to make a story about enslaved women that was more than just about slavery. In 1987, She told PBS NewsHour “If you focus on the characters and their interior life it's like putting the authority back into the hands of the slave it's rather than the slave holder” (6:08-6:17). In this interview with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, Morrison says she wanted to create a story of slaves as complex people with lives beyond their role in an inhumane system where one can see the “compulsion to nurture this ferocity that a woman has to be responsible for her children and at the same time the kind of tensions that exist in trying to be a separate complete individual” (PBS NewsHour, 3:32-3:46). This is well-portrayed when the novel, given its wide-spread reception was adapted into a film by Jonathan Demme in 1998, when the young Sethe (LisaGray Hamilton) kills her children, she isn’t a caricature in a white newspaper, but a real person, with fear for her life and her children and indignation toward her captors in her eyes (Beloved, 1:43:00-1:52:16). Her screams, her anguish and her emotion when she (Oprah Winfrey) retells it are all that of a person an audience can empathize with rather than the object that the archive often portrays slaves as, even in their own stories, which furthers Morrison’s goal (Beloved, 1:43:00-1:52:16; PBS NewsHour). In fact, Sethe is based on the real Margaret Garner, who has been studied extensively since. As author Rebecca Carroll said in a modern New York Times obituary of Garner “Only in these fictionalized versions of Garner are we given an idea of who she might have been as a black woman with an interior life, not just a runaway slave who committed a heinous crime … ‘what happens internally, emotionally, psychologically, when you are in fact enslaved and what you do in order to transcend that circumstance’ [as said by Morrison]” (Carroll). Toni Morrison’s work gave an idea of that interior life of Garner, Sethe, and others like them who were more than criminals and inspired continued interest in Garner’s life and the subject of slave infanticide in both press and film.

Before Beloved, there was It’s Morning, a much less famous 1940 play by Shirley Graham Du Bois, preserved in Kathy Perkin’s Black Female Playwrights: An Anthology of Plays before 1950, published in 1989. In the one act, two scene play, a slave in the deep south on the eve of 1853, Cisse, finds out her 14-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son are to be sold, and realizing her daughter will face the same sexual abuse she did and agonizing over not being able to protect her children, Cisse decides that night two throw them a party and then kill them in their sleep at dawn before they can be sold the next day (Graham Du Bois, 211-224). Cisse gets the idea from an older female slave who tells of women who came before her and did the same to save their children (Graham Du Bois, 216-217). In her analysis of It’s Morning and Beloved and the descriptions of infanticide, scholar Ama S. Wattley notes the similarities between Cisse and Sethe’s stories and motivations and covers the how Graham Du Bois’ play importantly portrays the role of Christianity in slaves lives, as Cisse is told by a reverend to trust in God to save her children and while another slave says that her children may be better off with him (Wattley, 58; Graham Du Bois, 221-222). Ironically, Cisse kills her daughter only to find out the white men at the door are there to free them so she must mourn the needless death of her child at her hands (Graham Du Bois 224). While nothing is written by Graham Du Bois herself on why she wrote the play, Wattley argues that is a way of carrying on this past and healing from it by remembering rather than trying to forget (62). She also highlights that like in Beloved, there is an importance in the portrayal of infanticide as a plural and generational form of resistance in It’s Morning and that collectivity is a part of Graham Du Bois’ contribution to the literature on this form of resistance (Wattley, 49)

Moving away from the United States, Haitian author Évelyne Trouillot’s first novel in 2003, The Infamous Rosalie, translated into English in 2013 by Marjorie Salvodon, with a foreword by fellow Haitian author Edwidge Danticat, tells the story of Lisette, a creole house slave and the third generation from a group of Arada women brought across the Middle Passage to Haiti. The group, comprised of her deceased mother Ayouba, deceased great-aunt Bridgette, grandmother Charlotte, and godmother Augustine, become a family with the latter two being alive to raise Lisette, who must now learn and hold on to the stories of their journey to America, the horrors and abuses they faced, and the circumstances of their lives as she must decide what her life will be as she becomes an adult during the poisoning scares and beginnings of revolt in the late 1750s (Trouillot 2013). As she becomes more aware of the intimacies of the lives and deaths of her fellow slaves, she finds out her rival Gracieuse, their master’s mistress, had used herbal remedies from the midwife to abort seven consecutive times with no rest, which ultimately kills her, because she vowed to never have children subject to the same cruelty she was (Trouillot 2013, 93-95). In the end Lisette learns about the looming mystery of Bridgette, a famous midwife’s, death, its connection to her garde-corps of knotted rope and her mother’s death post-birth – Bridgette had killed 70 babies she helped birth by giving them tetanus with a needle so they couldn’t breastfeed, an act known to have actually been done by Haitian midwives (Trouillot 2014 114-121, Eddins 141-145). Bridgette turns herself in because she cannot bear to kill Lisette at birth, a cognitive dissonance resulting in Ayouba’s death, but leaves the cord with a knot for each child, which Lisette now hold (Trouillot 2013, 114-121). Lisette soon after decides to run away, now pregnant, with the cord as a reminder of the sacrifices for freedom and saying “May I find the courage to honor my promise: Creole child who still lives in me, you will be born free and rebellious, or you will not be born at all” (Trouillot 2013, 129).

In her 2018 essay “Lakay se lakay, but where is lakay? Home is home but where is home?” Trouillot speaks about part of her goal in writing this narrative. She says “my writing provided me with the ability to present the enslaved as human beings… and I felt a certain comfort to have been able to do so…. This is the power of creative art: to take the realities of life, the present and the past, and create sense out of it” (Trouillot 2018, 17). Like Morrison and Graham Du Bois, her work emphasizes the generationality and plurality of acts of infanticide and their complexity (Trouillot 2018, 17). Uniquely, Trouillot cites the importance of writing about female slaves because of their lack of representation in the archive of the Haitian Revolution (2018, 17). She highlights these goals as well in her 2011 interview with PBS NewsHour (Extended Interview With Evelyne Trouillot, 3:18-4:06). Importantly, she also remarks to interviewer Jeffrey Brown that the story is meant to give an audience outside of Haiti a perspective of Haitians not just as struggling victims of natural disasters but a beautiful thriving people, many of whom around her inspired Lisette’s character (Extended Interview With Evelyne Trouillot, 3:18-4:06). In a printed interview for the Jamaican Daily Observer in 2020, she mentions that like Garner and Sethe, Bridgette is based on the story of a real woman, which she used writing and narrative to better process, understand and share with complexity (Toon). In their book review and published excerpt the authors of the history, politics, and culture collection The Haitian Reader write that Trouillot “fills in the gaps around that painful history [of slavery] via the memories of successive generations of enslaved women, taking the reader from the slave ship Rosalie through to the first stirrings of revolution in Saint-Domingue… [which] suggests a complement to far more prevalent histories of the Haitian Revolution and its heroes, evoking less spectacular quotidian instances of rebellion and triumph” (Glover et al., 19). Their review of her work to display the everyday details of women’s lives highlight the value of this novel to the literary dialogues of enslaved women of the Atlantic.

Morrison, Graham Du Bois, and Trouillot each add valuable work the literary and archival dialogue on the lives of enslaved women. While taxing, gruesome, and horrifying, these stories of infanticide give voice to the women left behind by the archive and fill in historical silences with an idea of these women as complex people with complex reasoning behind their actions. Their work given rise to engagement by scholars and the public which will, as all three hope, begin to help us remember the enslaved as people with lives beyond their chains who survived the unthinkable, believing it a worse fate than death. Within deaths, these three women bring life to a future of critical and intense engagement with the lives of enslaved women as mothers, daughters, friends, and members of a world beyond their bondage.

References

Beloved. Directed by Jonathan Demme, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1998, https://www.hulu.com/watch/fda24925-3d21-43dd-abf8-bdce92f5cdd9.

Bush, Barbara. “HARD LABOR.” More Than Chattel, edited by David Barry Gaspar and Darlene Clark Hine, Indiana University Press, 1996, pp. 193–217, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16xwc2q.13. JSTOR.

Carroll, Rebecca. “Margaret Garner, a Runaway Slave Who Killed Her Own Daughter.” The New York Times, 31 Jan. 2019. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/obituaries/margaret-garner-overlooked.html, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/obituaries/margaret-garner-overlooked.html.

Eddins, Crystal Nicole. Rituals, Runaways, and the Haitian Revolution: Collective Action in the African Diaspora. 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2022. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009256148.

Extended Interview With Evelyne Trouillot. Directed by PBS NewsHour, 2011. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3-mi6ZYKJQ.

Glover, Kaiama L., et al., editors. The Haiti Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, 2020.

Graham Du Bois, Shirley. “It’s Morning.” Black Female Playwrights an Anthology of Plays before 1950, by Kathy A. Perkins, Indiana University Press, 1989.

Morgan, Jennifer L. Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. 1st Vintage International ed, Vintage International, 2004.

Toni Morrison on Capturing a Mother’s “compulsion” to Nurture in “Beloved.” Directed by PBS NewsHour, 1987. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLQ6ipVRfrE.

Toon, Clovis. ‘There Is A Silence That Should Be Broken’: An Interview With Haitian Writer Évelyne Trouillot. 31 May 2020, https://www.pressreader.com/jamaica/daily-observer-jamaica/20200531/page/47/textview.

Trouillot, Évelyne. “Lakay Se Lakay, but Where Is Lakay? Home Is Home but Where Is Home?” Cultural Dynamics, vol. 30, no. 1–2, Feb. 2018, pp. 13–18. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374017751768.

Trouillot, Évelyne. The Infamous Rosalie =: Rosalie l’infâme. Translated by Marjorie Salvodon, University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

Turner, Felicity M. Proving Pregnancy: Gender, Law, and Medical Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century America. University of North Carolina Press, 2022.

Wattley, Ama S. “MATRILINEAL INFANTICIDE IN TONI MORRISON’S BELOVED AND SHIRLEY GRAHAM’S ‘IT’S MORNING.’” Journal of Intercultural Disciplines, vol. 6, Winter 2006, pp. 47–64. Ethnic NewsWatch, 223087205.

Weaver, Karol Kovalovich. “The Enslaved Healers of Eighteenth-Century Saint Domingue.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 76, no. 3, 2002, pp. 429–60. JSTOR.