Queen E

Jazz music, a genre of African American music, finds its historical origin and cultural concretization in New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 1800’s. The sound traversed state borders and made its way north, taking root in Chicago and New York. Eventually, in the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance—a movement denoted by the development of the Harlem, New York, neighborhood, and a time that signified the emergence of African American art into the popular American artistic landscape (Jones, 5)—helped popularize the genre and ushered in the “Jazz Age” within the contiguous United States.

The 1920s, also known as the “Roaring Twenties,” was a time of major change within the trajectory of American history and the development of American contemporary life. Within the background of jazz music’s rise to dominate the popular American soundscape, the First World War had ended, America was undergoing industrialization, and the Eighteenth Amendment prohibited the “manufacture, sale and transportation” (Britannica) of alcohol. Thus, the proliferation of Jazz was happening at a quintessential moment. The timing and the intermingled relationship between the different affairs have caused jazz practitioners, according to Ingrid Monson, a Jazz Scholar, and Ethnomusicologist at Harvard University, to “regard jazz as … “African American classical music.” (Monson, 163) The genre is idolized as a musical tradition. (Monson, 164)

"Oh No! Sex:" White Fear of Jazz

Unfortunately, due to the pervasiveness of anti-Blackness within the United States, new Black cultural products become quickly entangled with the troubles that plague Black life. Jazz became quickly pathologized for its association with sex (Davis, 26), which was vilified by the still conservative popular media.

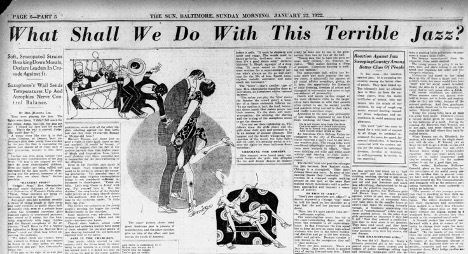

In 1922, The Baltimore Sun—a newspaper—published an article by a “Mrs. Martha Lee.” The name “Mrs. Martha Lee” was more than likely a pseudonym as there is no traceable information found about the author and the Sun “carefully avoided sharing any details about the author.” (Gioia) Regardless, “Lee” was a prolific writer for The Baltimore Sun, where she dedicated her words to discussing a conservative point of view against jazz music. On January 22, 1922, the Sun released Lee’s first article titled, “What Shall We Do With [sic] This Terrible Jazz?” The article is a synthesis of sensational opinions. Some of those whose stories were told in the article are “Judge Lindsey,” unnamed “Doctors,” and the “National Music Chairman of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs.” Their wills are clear: jazz music is dangerous, addicting, and immoral. Mrs. Oberndorfer, the national music chairman of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, charges jazz music with having the ability to “vicariously arouse” certain “instincts.” Within Lee’s article was a clear equation between jazz and sex, something seen as immoral in the public context. It can be inferred that the root of this belief is the fact that jazz music was associated with underground speakeasies where illegal alcoholic beverages were enjoyed. (Thomas) This context is evident as Lee states that, “hooch and harem parties … have become so wild … crowds often collect to see youths and maidens being carried to their cars.” Lee hints that the “youths and maidens” were either exhausted from dancing or drunk, which was illegal in 1922—all within a context where jazz music was played. This narrative insulting jazz music, excited and was demanded by an anti-jazz audience causing Mrs. Martha Lee to produce numerous other articles on the topic and then disappear from the paper a few months later. (Gioia)

The genre was within a lively and contentious debate in the United States. One of particular interest was about the genre’s place within the church—the White church. Within White churches, many saw jazz as “musical profanity” and a “rhythmic perversion.”

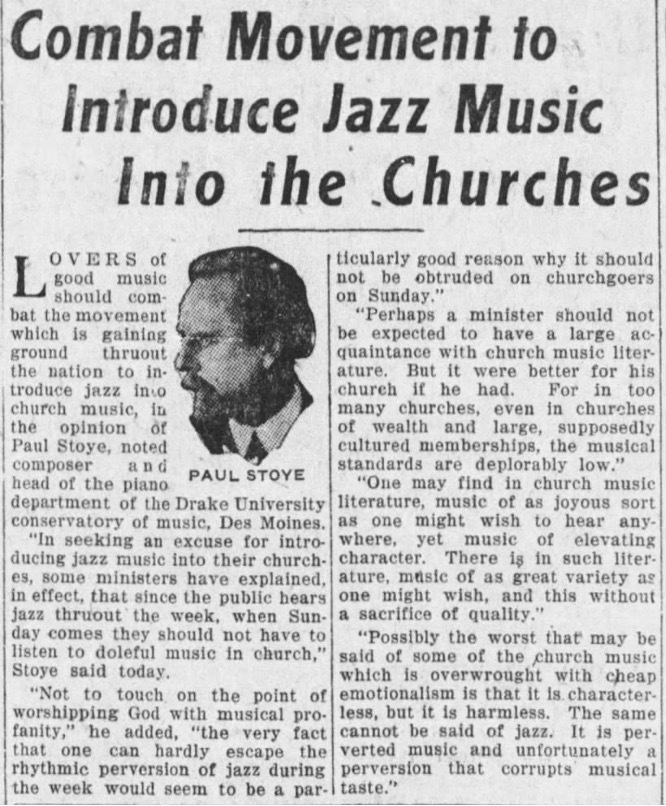

On April 4, 1926, The Quad City Times—a newspaper from the Mid-West United States—published an article that is titled by its demand to, “Combat Movement to Introduce Jazz Music into the Churches.” The writer, unnamed, writes the opinion of Paul Stoye, a composed and “head of the piano department of the Drake University conservatory [sic] of music.” It is unclear which church Stoye is referring to. However, this piece can be speculated to have been written in response to the growing trend of jazz music within Black churches. (Booker, 20) Therefore, White churchgoers, like Stoye, could have felt the need to announce their distaste for jazz entering the church and fear that jazz could take root in their churches. In the article, Stoye articulates that “ministers” are justifying the entrance of jazz into churches because people hear the sound every other day of the week. Therefore, in church, they shouldn’t have to listen to “doleful music.” Stoye, though talking in context to the church, pathologizes the entire genre of jazz music. He insults it as “cheap emotionalism” and a “perversion that corrupts musical taste.” The usage of the word “perversion” is interesting because it is traditionally associated with abnormal “sexual behavior.” (Oxford Learners Dictionaries) Therefore, even within Stoye’s statements, one can see that his perspective of jazz concerns sex.

It can be argued that this equation between jazz and sex stems from the hyper-sexualization of Black people—the genre’s creators. (Cunningham, 3) Black people experience “Negrophilia” and “Negrophobia”—the sexual fascination and the irrational hatred of Blackness. (Wilderson, 15) This explains a level of gratuitous violence—in the forms of physical and sexual violation--enacted on Black people during the plantation. Jazz, a creation of Black people, was seen as an extended site to enact anti-Blackness. Therefore, the genre experienced sexualization and pathologization by the larger American civil society.

Sexual Objectification of Black Women in Jazz

Though the genre experienced external backlash and antagonization, there was turmoil within the genre itself. Jazz, particularly Bebop—a subgenre of jazz characterized by the artist’s improvisation and fast tempo,—had a masculine ethos. This anticipated masculine sound and form of jazz gave Black men an advantage at the expense of Black women. Victoria Smith, in “Listen to Liston: Examining the Systemic Erasure of Black Women in the Historiography of Jazz,” states that the masculine ethos, “was not accessible to black women, and in many ways, it perpetuated a culture of misogynoir within bebop.” (6) Despite not being able to access jazz from the position of an artist, Black women were already and always associated with the image of jazz in the early 1900s. (Davis, 15) Therefore, in the big picture of jazz history, Black women were held culpable for their sexualization within jazz, yet Black men were the primary actors and popular creators within jazz music.

In a male-dominated Jazz industry, one of the forms that misogynoir—prejudice against Black women—took is the sexual objectification of Black women by Black men within their performances, songs and aesthetics. For precision, sexual objectification is the act of “treating a person as a body or collection of body parts.” (Ward et al., 3)

Tampa Red and Georgia Tom, whose real names are Hudson Whittaker and Thomas A. Dorsey, released the song, “It’s Tight Like That” on October 24, 1928. The musicians, based in Chicago tell a story about a man— “a little black rooster”—and a woman—"little brown hen”—having relations that are hinted as sexual. Though the lyrics of the song are not overtly sexual, the title of the song clues the audience in on an innuendo. “It’s Tight Like That” within the larger narrative of the song refers to being close to someone. However, it serves as a double entendre to refer to the feeling of intercourse from the male perspective within a hetersexual relationship. The title slyly describes an attribute of a woman’s genitalia: "tight."

The song was successful and sold over seven million copies in its time—which is noted to be an “extraordinary achievement of the time.” (Staig) Interestingly, Tampa Red became a popular mainstream musician, even noted to be known as one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s favorite artists. (Staig) So, we can draw that the sexualization of women was palatable for the Tampa Red and George Tom’s audience at the time. From the song's popularity, it can be inferred that their listeners enjoyed the song and that it had the potential to inspire the production of other songs that sexualized women.

Another more overt example of this sexualization is within Bull Moose Johnson’s, “I Want A Bowlegged Woman.” Bull Moose Johnson, whose real name was Benjamin Joseph Johnson, was known as a “dirty blues” performer. The song, released in 1947, details Johnson’s desire for a bowlegged woman. Bowlegged is a condition that causes one’s legs to curve outward, which tends to overexpose the pelvis. Johnson states that he’ll “fall in love … right from the start/ because her big fat legs are so far apart.” He is playing with the idea of a woman’s pelvis protruding. Johnson is fetishizing the physical nature of being bowlegged. Johnson is thinking from a libidinous point of view—that he wants the woman purely for his sexual gratification as, to him, her pelvis is more readily exposed or is eye-capturing.

Though Johnson’s yearnings might be an exaggeration, his narrative craftswomen as sexual objects that have a “solid straddle” and must have “hoofs like an old bill bear” for fellatio. The song reveals how the physical appearance of a woman—for a sexual purpose—is important to society.

It is unclear what provoked the writers, Henry Glover and Sally Nix, to write this song and why Johnson choose to publish anthem. However, Bull Moose Johnson was already popular within the music industry and could have speculated that there would be a positive reaction to the song. (Hollen) When the song was released, it was seen to have “resonated with audiences because it tapped into their shared desires and preferences.” (Hollen) It would be reasonable to assume that Johnson’s audience was primarily men because “for jazz, the gender gap is largest in favour of men.” (McAndrew and Widdop, 9)

This sexualization continued throughout the late 1900s, with the development of soul music—known as a musical progression that stems from jazz music but is sonically denoted as a fusion of blues and jazz. The “genres overlapped considerably” and their musical history is intimately intertwined. (Monson, 163; Maultsby, 277) Therefore, this presentation draws from genres where the sonic boundaries are blurred and were popular within the same century: blues, jazz, and soul music.

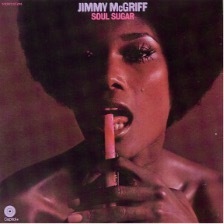

In 1970, Jimmy McGriff, a soul-jazz musician from Pennsylvania, released his album, Soul Sugar. On the front cover of the album is a photo of a Black woman staring at the camera and suggestively licking what appears to be a large candy cane. The woman is beautiful, wearing her hair in a natural afro and her face is decorated with light makeup. The photo is not arrogant in its sexual implication. Rather, it is sly. The cover proceeds to communicate a sexual idea through the gaze that the woman holds as she opens her mouth to lick the candy. It is implying fellatio. The back of the record is a little more overt. The woman’s top is more exposed. The audience can see that she is topless as she licks the piece of candy.

The cover art copyright belongs to Capitol Records, Jimmy McGriff’s record label. There is no indication of who the photographer is and why this image was chosen for the cover. However, all the album’s tracklist names are also suggestive. For example, McGriff has a song called, “Fat Cakes,” which is meant to suggest the behind of a woman.

Therefore, it can be inferred that the aesthetic and sonic aura of the album was supposed too sexual and sultry. This was the perspective of McGriff’s audience at the time of the album’s release. (Discogs) The album was not the most popular set of tracks within McGriff’s discography. However, it has a rating of 4.42 out of 5 in terms of quality and execution. (Discogs) This gives us evidence that there is a market for the sexualization of women within music.

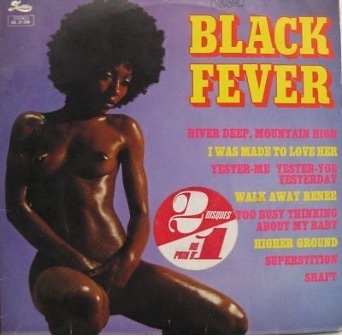

The Harlem Soul Brothers in 1975, took a similar approach as Jimmy McGriff to grasp audiences' attention. The Harlem Soul Brothers are a group of American artists that performed soul-jazz music. However, the album was produced by Locomotive, a French record label, and was released in France. (Discogs) Despite this, the album is currently owned and copyrighted by RCA records, an American media company. (Discogs)

The cover of their album “Black Fever,” is a naked Black woman. The woman is almost completely exposed with her hands positioned in a manner that suggests auto-eroticism. Interestingly, the album is almost completely out of circulation in the United States. The photograph is taken by Michel Laguens, a French photographer. It is interesting that this album was produced and released in France and was shot by a French photographer. This tells us, in the context of the album cover, that Black women were within the sexual imagination in the larger Western world. When jazz spread to France in 1920, (Archer-Straw, 3) there became a growing fetishization of Blackness and Black people especially in Paris. This became a movement was called “negrophilie”—a sexual obsession with Blackness. (Archer-Straw, 10) Petrine Archer-Straw, in her book Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s, asserts that this phenomenon became prominent after the introduction of jazz to France. (11) Though the album was not produced in the United States, it serves as evidence for how jazz music because a medium for the sexualization and objectification for Black women. This medium is then used to communicate, inspire, and proliferate this message—exacerbating the issue.

It is important to notice that throughout these different artifacts, there is no mention of a woman’s consent or pleasure despite the focus being on women as sexual beings. These artifacts sexually objectify women—particularly Black women.

Erotic Black Women in Jazz

Sexual objectification is dehumanization. Focusing on women for their bodies and how their bodies can provide sexual gratification, symbolically constructs Black women as objects. The impact of sexual objectification is that the victims are “perceived more negatively, and as less competent and less fully human than women who are not sexually objectified.” (Ward et al., 4) White slave owners sexually objectified Black women and used this logic to justify rape.

Though sexuality has been weaponized against Black women, sex can also exist as a liberatory tool. (Lindsey and Johnson, 3) Furthermore, doing away with sex in the dialogue on the lives of Black women is unrealistic and unfair because they deserve the freedom to access sexual pleasure without pathology. Within jazz music, in the face of this subjugation and denial of sexual respect, Black women were actively asserting their autonomy and personhood regarding sexuality. Ma Rainey, Lucille Bogan, Helen Humes, and Dinah Washington discuss moments of sexual fornication within their music. Rather than cowering, they asserted themselves in the musical soundscape as erotic subjects and focused on their pleasure. This focus on pleasure is powerful because it combats the narrative that Black women are objects for the sexual gratification of others. (Lorde, 3) Within the stories crafted in each of the Black women’s songs, they are beings that require consent and will engage in sexual acts that please themselves.

Gertrude “Ma” Rainey was a blues musician. In her early life, she was a minstrel and tent-show singer, which required her to be provocative to capture and keep the audience’s attention. (Smith, 43) Rainey on September 6, 1924, released the first version of “Shave ‘Em Dry.” The song is about aggressive intercourse where there is no intimacy involved. However, Rainey crafts the song to think about her pleasure. Later in 1935, Lucille Bogan pushes the boundaries and alters the song to be more sexually explicit. In the song, she is bold as she begins by admiring and describing her body. She says, “I got nipples on my titties, big as the end of my thumb/ I got something between my legs’ll make a dead man cum.” Rainey is boasting that she is a desirable woman. However, she pushes past self-objectification and asserts what she desires: to be pleased. She sings, “Oh, daddy, baby, won’t you shave ‘em dry?” She is articulating to her partner that she is consenting and wants the act. The most subversive part of the song is when she states that she wants to be “grind[ed] … until [she cries].” She makes it clear that the act is on her terms for her pleasure.

It is unclear where Rainey or Bogan performed “Shave ‘Em Dry.” However, their audience within minstrel shows were primarily middle-class men. (Smith, 45) Therefore, they could have been inspired by their experiences and knew that a raunchy song would capture the attention of men. This is important to them as an entertainer because it means making revenue. However, rather than continuing from a point of self-objectification, which is what was popular and what men were used to as they held power within the music industry, Rainey and Bogan were aggressive. They asserts their personhood and pleasure within the different versions of the song. As said by Angela Davis, Rainey’s performance is an aggressive rupturing of the current gender relations in music and within the larger United States. (112) This, too can be said about Bogan, who follows in Rainey's footsteps with her more sexual rendition of "Shave 'Em Dry."

A famous Black female musician known for her unapologetically sexually explicit lyrics is Lucille Bogan—born as Lucile Anderson but better known by her pseudonym, Bessie Jackson. Bogan was born in either Amory, Mississippi, or Birmingham, Alabama. Bogan was speculated to be a prostitute “at some stage of her life” and had strong connections with the Black “underworld”—a social sphere known to encompass organized crime. (Hymes) Though it could be an artistic fabulation, Bogan releases “Tricks Ain’t Walking No More” where she discusses life as a prostitute during a time of economic hardship. The song was released in 1930, which was a year after the national financial collapse known as the Great Depression happened in the United States. (Richardson)

Within the song, she articulates that “times done got hard, money’s done got scarce” and that she’s “got to change [her] luck.” Here, Bogan is articulating that she is consenting to sex and is receiving monetary compensation for her services. However, during the Great Depression, she has a lack of “tricks”—customers—and is even in a sorrowful state caused by the lack of business. This challenges the traditional narrative of women as objects because Bogan, from her perspective shown in the song, is in control. She is a woman who is using sex for her financial advantage.

Even within the title of the song, “I’m Gonna Let Him Ride,” Helen Humes announces her autonomy and consent. She states that she allows the sex act to commence. The man’s desire for her is pushed to the background and almost is completely non-existent within the song. Instead, she brings to the forefront her desire to be pleased by sex.

“I’m Gonna Let Him Ride,” was released in August of 1950. Humes begins the song by exclaiming, “he may be a man, but he comes to see me sometimes.” In the recording of her performance, she sounds proud of the fact that the man comes to see her. The song is about her sexual relationship with a man who probably sleeps with a lot of other women. Humes sings that the man “rocks” her. She is enjoying their sexual relationship within her story. She continues that “when he rocks [her], he satisfies [her] soul.” Within the song, she does not objectify herself. She is purely focused on her pleasure and how she is pleased by having sex with the man.

Humes was a blue and jazz musician from Louisville, Kentucky. When “I’m Gonna Let Him Ride” was released, Humes was already an established musician, famously performing in the Cotton Club in Cincinnati, Renaissance Club in New York City, and with the Count Basie Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. (Dahl, 230) Therefore, it is important to note that Humes probably had more space to focus on her pleasure because she was already an established musician. She was known for her talent and people were going to come watch her sing regardless. This is different compared to Ma Rainey and Lucille Bogan when they first started discussing their sexuality within their music.

Dinah Washington was a jazz vocalist from Tuscaloosa, Alabama. In the earlier part of her career, she was a pianist for St. Luke’s Baptist Church and eventually became involved as a singer in a Gospel Choir. (Bogdanov, 373) In her twenties, she was performing in Chicago clubs. Furthermore, before the release of, “Big Long Sliding Thing,” Washington had 27 R&B top-10 hits. She was noted as one of the most popular singers of her time. (Joravsky) So, when Washington released “Big Long Sliding Thing” in 1954, she was already wildly successful. The song begins with a seductive composition that allows Washington to insert herself within the song as a woman in control of the piece. The song is about finding a trombone player. A “Big Long Sliding Thing” refers to the trombone. However, there is a hidden innuendo referring to a man’s genitalia. Washington plays into this innuendo in the lyrics:

“He said, "I came to do some tinklin'

On your piano keys!".

I said, "Don't make me nervous,

This ain't no time to tease!

Just send me my daddy,

Send me my daddy with that big long slidin' thing!" (Washington)

She says that she is being “tease[d]” by her “daddy”—a well-known sexual pet name (The Economic Times)—insinuates a sexual reference.

The song was written by Leroy Kirkland and Mamie Thomas. (International Lyrics Playground) The song, sung by a woman, provides an innuendo about her trombone-playing boyfriend’s phallus. This is an inversion of social norms. Traditionally, men were discussing women’s body parts and sexualizing them. However, Washington is a woman sexualizing a man—her known boyfriend at the time, Gus Chappell. (NPR) It is important to note that Washington is not objectifying Chappell. The song and Washington’s performance of the song is erotic rather than pornographic, which “emphasizes sensation without feeling.” (Lorde, 2) Audre Lorde, in “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” states that the erotic is “a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings. It is an internal sense of satisfaction.” In tangible terms, it is “sharing joy” “with another person”—feeling. (Lorde, 5) In the song, Washington is looking for a very specific man—her “daddy.” Even though she sexualized the situation, the crux of the story is finding her boyfriend and being calmed by his presence. For example, Washington within the context of the song, believes the trombone is a “broke down piece o’ junk!” and therefore, she “need[s her] daddy.” She articulates her conundrum from a place of vulnerability and almost a need to be helped by her boyfriend. The song—as evidenced by the lyrics and Washington’s vocal performance—trends toward romantic but has sexual references.

Conclusion

Within these songs, Lucille, Hellen, Dinah, and Ma Rainey, were asserting that as humans, they were sexual beings. They were fighting for their freedom to be respected even in context to sex and sexuality. They disproved the narrative spun based on their objectification by showcasing their capability of the erotic and their demand for pleasure. They undeniably flipped the script: they were announcing to the world that they were not tools. Instead, that they were looking to be pleased—just like everyone else.

Works Cited

Archer Straw, Petrine. Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s. Thames & Hudson, 2000.

“Big Long Sliding Thing .” International Lyrics Playground, 2011, https://lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/b/biglongslidinthing.html.

Bogdanov, Vladimir, et al., editors. All Music Guide to the Blues: The Definitive Guide to the Blues. 3rd ed, Publishers Group West , 2003.

Burnim, Mellonee V., and Portia K. Maultsby, editors. African American Music: An Introduction. Second edition, Routledge, 2015.

“Composer Expresses Opposition to Jazz Music Being Played in Churches.” Quad-City Times, 4 Apr. 1926, p. 15. newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/article/quad-city-times-composer-expresses-oppos/28109263/.

Cunningham, Alexandria. “Make It Nasty: Black Women’s Sexual Anthems and the Evolution of the Erotic Stage.” Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018, pp. 63–89. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1353/bsr.2018.0015.

Dahl, Linda. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen. 1st Limelight ed, Limelight Editions, 1989.

Dance, Stanley. The World of Count Basie. Da Capo Press, 1985.

Davis, Angela Y. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. Penguin Random House, 1999, https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/37351/blues-legacies-and-black-feminism-by-angela-y-davis/.

“Dinah Washington: A Queen in Turmoil.” Weekend Edition Sunday, directed by N et al., NPR, 29 Aug. 2004. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2004/08/29/3872390/dinah-washington-a-queen-in-turmoil.

Ducille, Ann. “Blues Notes on Black Sexuality: Sex and the Texts of Jessie Fauset and Nella Larsen.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 3, no. 3, 1993, pp. 418–44. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3704015.

Gioia, Ted. How an Angry Woman in Baltimore Almost Killed the Jazz Age. https://www.honest-broker.com/p/how-an-angry-woman-in-baltimore-almost. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Gregory, Paul. “Eroticism and Love.” American Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 4, 1988, pp. 339–44. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20014257.

“Helen Humes Songs, Albums, Reviews, Bio & More.” AllMusic, https://www.allmusic.com/artist/helen-humes-mn0000671800. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Hollen, Joseph L. “The Meaning Behind The Song: I Want a Bowlegged Woman by Bull Moose Jackson.” Old-Time Music, 2 Oct. 2023, https://oldtimemusic.com/the-meaning-behind-the-song-i-want-a-bowlegged-woman-by-bull-moose-jackson/.

Humes, Helen. I’m Gonna Let Him Ride. 2020. www.youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5R0BesEAaCU.

Hymes, Max. Spotlight on Lucille Bogan - Part 5 (Conclusion). 2001, https://www.earlyblues.com/Lucille5.htm#:~:text=Bogan%20was%20definitely%20a%20prostitute,Library%20of%20Congress%20in%201934.

Jones, Sharon L. Rereading the Harlem Renaissance: Race, Class, and Gender in the Fiction of Jessie Fauset, Zora Neale Hurston, and Dorothy West. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Joravsky, Ben. “Dinah Was...and Wasn’t.” Chicago Reader, 16 Dec. 1999, http://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/dinah-was-and-wasnt/.

“Jul 17, 1954, Page 7 - The Times at Newspapers.Com.” Newspapers.Com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/51867241/. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Lewis, Nghana tamu. “In a Different Chord: Interpreting the Relations among Black Female Sexuality, Agency, and the Blues.” African American Review, vol. 37, no. 4, 2003, pp. 599–609. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1512389.

“Lift Every Voice and Swing.” NYU Press, https://nyupress.org/9781479890804/lift-every-voice-and-swing. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Lindsey, Treva B., and Jessica Marie Johnson. “Searching for Climax: Black Erotic Lives in Slavery and Freedom.” Meridians, vol. 12, no. 2, 2014, pp. 169–95. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2979/meridians.12.2.169.

Lorde, Audre. Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. Crossing Press, 1978.

McAndrew, Siobhan, and Paul Widdop. “1 Gender Inequalities in the Consumption and Production of Jazz: Perspectives from Genre-Specific Survey and Social Network Analysis.” Center for Open Science, Center for Open Science, Apr. 2020.

Monson, Ingrid. “Jazz.” African American Music: An Introduction, Second edition, Routledge, 2015.

O’Donnell, Patrick. “Ontology, Experience, and Social Death: On Frank Wilderson’s Afropessimism .” APA Newsletter, American Psychology Association, 2020, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://philarchive.org/archive/ODOOEA.

Prohibition | Definition, History, Eighteenth Amendment, & Repeal | Britannica. 5 Feb. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Prohibition-United-States-history-1920-1933.

Perversion Noun - Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes | Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.Com. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/perversion. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

Ruiz, María Isabel Romero. “Black States of Desire: Josephine Baker, Identity and the Sexual Black Body”.” Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, no. 16, 2012. revistascientificas.us.es, https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/ESTUDIOS_NORTEAMERICANOS/article/view/4670.

“Sex Therapist Tells Why Women Call Men ‘Daddy’ during Sex.” The Times of India, 14 July 2018. The Economic Times - The Times of India, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/health-news/sex-therapist-tells-why-women-call-men-daddy-during-sex/articleshow/64988167.cms.

Smith, Jessie Carney, and Shirelle Phelps, editors. Notable Black American Women. Gale Research, 1992.

Smith, Peter Dunbaugh. Ashley Street Blues: Racial Uplift and the Commodification of Vernacular Performance in Lavilla, Florida, 1896-1916. 2006. diginole.lib.fsu.edu, https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu%3A168486/.

Smith, Victoria. “Listen to Liston: Examining the Systemic Erasure of Black Women in the Historiography of Jazz.” Theses, Jan. 2020, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/le_etds/8.

Staig, Laurence. “Obituary: Thomas Dorsey | The Independent.” The Independent, 26 Jan. 1993. www.independent.co.uk, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-thomas-dorsey-1480857.html.

The Great Depression | Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-depression. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.

“The Harlem Soul Brothers--Black Fever.” Discogs, 1975, https://www.discogs.com/sell/release/2950489?ev=rb.

Thomas, Heather. “American Fads and Crazes: 1920s | Headlines & Heroes.” The Library of Congress, 24 Jan. 2023, https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2023/01/american-fads-and-crazes-1920s.

Ward, L. Monique, et al. “The Sources and Consequences of Sexual Objectification.” Nature Reviews Psychology, vol. 2, no. 8, May 2023, pp. 496–513. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00192-x.

Wilderson, Frank B. Afropessimism. Liveright paperback, Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2021.