Rawan H

Introduction

The current genocide in Sudan opens up questions about the ways that Sudanese people and the world understand what it means to experience having an identity being stripped away. Today, Sudanese land and Sudanese people are being killed and forced to flee the country, putting the Sudanese identity at risk. The war in Sudan is the result of an ongoing internal conflict that can be traced back to the settlement of outside forces, and colonialism. Now, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary and Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) in Sudan are in the middle of a war that has not been mediated, has led to a genocide, and is being funded by external powers including the UAE. This war and genocide, like many others, has led to the use of strategies by the military that aim to demonstrate a sense of control and honor. For instance, sexual violence is among the main forms of abuse and control that the military has on Sudanese people. This is a known form of control, however, the hesitance around talking abut the daily cases of women who experience sexual violence in Sudan is what drives the research on how Sudanese people themselves approach this specific violence.

Further, In this essay, I will explore the following question: How are Sudanese people responding to the ongoing sexual violence against women and girls in Sudan? I will argue that Sudanese people continue to use social media to spread the control of the RSF and SAF, as well as the use of art. I will do so by first situating and describing the war and genocide then explaining how Sudanese people are talking about and describing the sexual violence taking place and their own experiences, then through assessing how the role of the UN as an international organizations has addressed sexual violence in Sudan, as a point of departure and contrast. Moreover, my argument will be demonstrated through the incorporation of discourse on gender violence and resistance.

What exactly is going on in Sudan? Who is most affected?

In April of 2023, the war between the RSF and SAF started. It is integral to understand, however, that there was already ongoing violence and fighting between the two forces and that a lot of the violence imposed on civilians was in regions that have experienced this violence for decades. Based on a UN Security Council Press Statement Report on December 22, 2023, the humanitarian situation in Sudan is indeed deteriorating:

This report is imperative to note, as it mentions the ways that the Security Council plans to intervene and provide aid to the country, yet there is little to nothing actually being done to, at the least, protect victims of sexual violence.

An example, among many, of the presence of the RSF and their use of intimidation and control in Sudan, is exemplified in the following video

In this video, a Sudanese man is recording the RSF driving through a street in Sudan, while he says “May God Protect Us.” This is just an example of where both the RSF and SAF make their presence known as a form of intimidation in Sudan. Sudanese people often record these instances, and share them on platforms that end up being widespread.

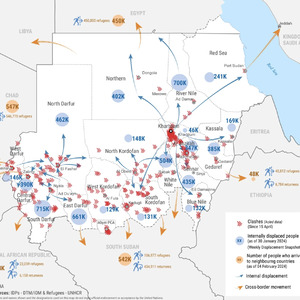

One of these region that is most affected by this war and genocide is Darfur, which is in the western region of Sudan. When Omar Al-Bashir was dictating Sudan, he financed a genocide in Darfur that was carried out by the RSF. The RSF is made up of soldiers from the Darfur region, but ones from the Arabized tribes. The RSF had agreed to carry out a genocide in their own region, but against those who are indigenous to the area. For context, the following map shows where Darfur is, and the amount of clashes in comparison to the rest of the country

One of their main tools of abuse, was sexual violence, and the genocide in Darfur is when Sudanese people had become increasingly aware of this tactic that the RSF would use. While today the RSF is murdering Sudanese people across the entire country, people in Darfur are the most impacted given tribal, cultural, and ancestral differences. Racism and colonization are deeply tied to what is happening to women in Sudan and how it specifically impacts women in Darfur. It is a common idea that those in the west of Sudan are less “Sudanese” and therefore should be stripped of their autonomy.

Further, when thinking about autonomy and what it means for Sudanese girls and women growing up, Johnson’s White Gloves, Black Nation describes what it was like for young Haitian girls in a way that is so similar to Sudan. Young Haitian girls essentially understood what it means to be and mature both physically and emotionally while under occupation (Johnson 44). In Sudan, young girls were and still are taught how to leave the house, what to wear, who to speak to, etc. Similarly to Haiti, Sudanese women tell young women about how these violent men think and our “place” in society. However, Sudanese people explain with little to no detail given the hesitance around the topic of gender violence itself. While Haiti and Sudan’s cases are different in terms of who is occupying their nations, race is still one of the main factors that brought them to these circumstances.

How Sudanese people are talking about and describing the sexual violence in Sudan

Sudanese people are talking about and describing the sexual violence taking place through their own experiences, and this has been shown through the use of social media and art. Throughout the Sudanese revolutions that have been taking place around the world, Sudanese women have historically had a symbol of a Kandaka. Kandakas were women who led Ancient Nubia and Kush that symbolize strength. A Kandaka was known to wear a white thobe, and now, if a Sudanese woman is seen in a white thobe it is an act of strength.

One of the images from the 2018 revolution, was of a woman or, ”Kandaka”, in a white thobe:

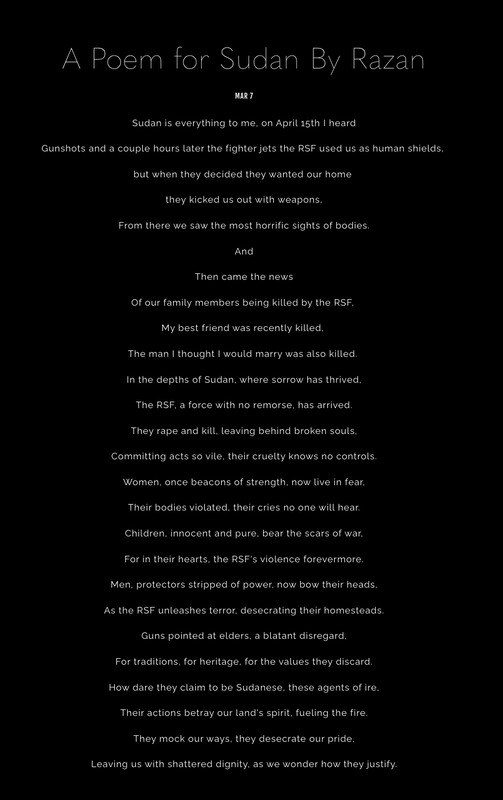

This picture embodies a sense of history that many Sudanese people are reminded of mainly during times of protest. While gender based violence has been an ongoign issue, this war and genocide has now decreased this same sense of strength that Kandaka embodied. However, this may have more to do with the fact that sexual violence has now spread increasingly throughout the entire country, rather than just in Darfur. It has been used as a tool to silence and impose fear on Sudanese women across the country. Sudan Speaks, is a platform that publishes pieces by Sudanese people who want to share their stories and their forms of art that embody the Sudanese experience and the current war. A poem published by a Sudanese woman, Razan, titled "A Poem for Sudan" speaks to this exact issue that Sudanese women are now being silenced:

This further opens up discourse on what it means to live in a society that is hesitant to speak on gender based violence as she says: Their bodies violated, their cries no one will hear.

Sudanese people often believe that the reason as to why the RSF use sexual violence is because they know that it brings shame to a family, so they harm women and girls in front of their families and fathers as a form of humiliation.

Circling back to how women of Darfur have historically been most targeted for sexual violence, a study that aimed to understand if sexual violence in Darfur was racially targeted, had a sample of refugees from Darfur who reported that the sexual violence was indeed racially targeted. This sample of 1,136 Darfur refugees in Chad, included people from various tribes, ethnic background, and gender, employment, education, and clan (Hagan et al. 20). This is integral to note, as darfur is made of different tribes and ethnicities. This further helps the researchers understand ether codes for rape were more prevlent among those of “African” tribes as opposed to “Arab” ones. Indeed, it was found and suggested that the Janjaweed, or RSF, were targeting more African villages as they would “spare” the Arab villages (Hagan et al 20). A woman from Darfur speaks on her experience, and this specific racially targeted gender-based violence:

This quote is from a study that was also done to understand sexual violence in Sudan in term of race and who is most targeted. Additionally, this further questions the idea of what it even means to be from an “Arab” or “African” tribe. This wording has been passed down through generations after Arabs settled and arguably colonized Sudan. In a statement by Hiba Babiker, a Sudanese woman who also speaks up on Sudan Speaks says:

The war in Sudan is a representation of colonization and ideas of what it means to be worthy of life and autonomy. It is a representation of how colorism is discussed when it comes to sexual violence around the world. The stories of Sudanese women and how they view their ethnicity, and what it means to be a Sudanese woman has been challenged by violent regimes throughout the entirety of Sudan’s history.

Assessing how the role of the UN as an international organizations has addressed sexual violence in Sudan

Given the lack of intervention and compassion towards the people of Sudan from international organizations, this section aims to analyze how the UN has addressed the sexual violence in Sudan throughout the past year. As opposed to understanding how Sudanese people describe this gender based violence and their experiences, the UN’s reports yet lack of meaningful assistance for Sudanese women will be assessed. In a press release in August of 2023, the UN describes the increase of sexual violence towards woman nd girls by the RSF. They stated their “solution” as the following:

This press release from August 2023 more-so focuses on how the sexual violence taking place in Sudan is a humanitarian violation. It states that intervention is challenging because of the war or fighting itself. It also mentions that they will investigate this violation, however it has been months since August and the violence continues. This is one of the clear examples of how international organizations such as the UN may provide information and updates on circumstances that are killing and traumatizing Sudanese people, yet fail to provide safety for the women. November of 2023, another press release by the UN states updates on Sudan:

Even by November, there is no clear message that states action that will be done by the UN to provide assistance and safety for women. In January 2024, the Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator mentions the increase of sexual violence in his statement that:

However, there is also no clear statement that offers insight into any assistance that will be made for victims of sexual violence in Sudan. These statements provide a perspective of what international organizations are currently doing to address the sexual violence in Sudan, as opposed to the voices of Sudanese women themselves. As the violence continues, it is clear that the experience of women, and specifically Black women around the world is often dismissed. This is seen throughout the ongoing experiences of women and children across the diaspora, and through the lack of compassion from international organizations.

Conclusion

Through the use of social media platforms and art, Sudanese people have expressed their stories and history to provide context to the sexual violence that Sudanese women are experiencing and the war overall. While there is hesitancy to speak on this issue in Sudan, there are still sources that speak to the gender-based violence and resilience that has been going on through many regimes. It is essential to understand that there is little to nothing being done to provide safety and care for the victims in Sudan, despite media coverage and international organizations' reports. Instead, Sudanese people are utilizing poems, their history, and are spreading videos of the violence they are enduring through various platforms. It is also essential to understand that the experiences of Black women and girls throughout the diaspora are closely tied, through their shared history of colonization that have exacerbated ethnic and tribal conflicts. Additionally, it is clear that these shared histories of colonization and racism have led to increased internalized racism based on ethnic background that have led to colorism and elitism.

Works Cited

- Amnesty International USA, "Sudan: Darfur: Rape as a weapon of war: sexual violence and its consequences", 26 Mar. 2011, www.amnestyusa.org/reports/sudan-darfur-rape-as-a-weapon-of-war-sexual-violence-and-its-consequences/.

- Hagan, John, et al. “Racial Targeting of Sexual Violence in Darfur.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 99, no. 8, 1 Aug. 2009, pp. 1386–1392, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2707480/, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.141119.

- Johnson S. Grace, “White Gloves, Black Nation'', University of North Carolina Press, Accessed 11 Mar. 2024, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469673707_sandersjohnson.5

- OCHA. “Sudan.” Reports.unocha.org, 23 Feb. 2024, reports.unocha.org/en/country/sudan/.

- OCHA, “UN Relief Chief: 2024 Demands Swift Action to Stem Sudan’s Ruinous Conflict", www.unocha.org, www.unocha.org/news/un-relief-chief-2024-demands-swift-action-stem-sudans-ruinous-conflict.

- “Security Council Press Statement on Humanitarian Situation in Sudan | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” Press.un.org, press.un.org/en/2023/sc15547.doc.htm. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

- Sudanesearchive.org, 2019, sudanesearchive.org/en/database/unit/OBS000131. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

- Teaching While Muslim, “Not Enough Outrage from Both Sudanese People and the International Community; We Are Rejected by Both.”, www.teachingwhilemuslim.org/sudan-speaks/2024/1/16/not-enough-outrage-from-both-sudanese-people-and-the-international-community-we-are-rejected-by-both. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024

- Kandaka, “Sudan Uprising – the Voice of a Woman Is a Revolution.” 11 Apr. 2019, kandaka.blog/2019/04/11/sudan-uprising-the-voice-of-a-woman-is-a-revolution/.

- Teaching While Muslim, “A Poem for Sudan by Razan.” www.teachingwhilemuslim.org/sudan-speaks/2024/3/7/a-poem-for-sudan-by-razannbsp. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “UN Experts Alarmed by Reported Widespread Use of Rape and Sexual Violence against Women and Girls by RSF” in Sudan., 17 Aug. 2023, www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/08/un-experts-alarmed-reported-widespread-use-rape-and-sexual-violence-against#:~:text=GENEVA%20(17%20August%202023)%20%E2%80%93,end%20to%20the%20%20ongoing%20violence.

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, "Sudan: UN Experts Appalled by Use of Sexual Violence as a Tool of War", 30 Nov. 2023, www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/11/sudan-un-experts-appalled-use-sexual-violence-tool-war.