Samantha H

Introduction

In the plantation South, black women undertook a wide range of roles, from laboring in the fields to tending to domestic chores. Among these tasks, domestic chores often nurtured skills such as sewing, leading some women to become seamstresses like Elizabeth Keckley, whose story illuminates how black women leveraged their labor to achieve freedom through emancipation. Tracing the labor of black women unveils a narrative of resilience and attempts at self-expression within the constraints of their daily lives. Their labor, whether in the field or in domestic skills, asserted economic value and served as avenues for enslaved women to recreate themselves and express self-identity. Despite facing severe restrictions—limited access to materials, time constraints, and little autonomy over their bodies—enslaved women exhibited resourcefulness and creativity in expressing themselves through clothing and adornment. Fashion, in this context, was about fashioning the body—a powerful tool of self-expression, allowing enslaved women to transcend their circumstances and assert their humanity. Looking into the history of women's skill and labor, it is evident that these expressions evolved from the struggles and triumphs of enslaved women in the plantation South. Fashion symbolized notions of freedom and the spirit of resilience and resistance against oppression.

Elizabeth Keckley: A Beacon of Skill and Resilience

Elizabeth Keckley’s story is heard widely, given her role as the dressmaker for one of the first ladies of the US, Mary Todd Lincoln. What makes her narrative particularly memorable is her use of personal labor to secure emancipation and establish independence. Born a slave in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, in 1818, Keckley rose to prominence through her exceptional skills as a seamstress, writer, and philanthropist. By leveraging the earnings from her sewing, she achieved freedom from slavery in 1855 (CITATION), showcasing her unwavering resilience and determination to carve out a future of freedom.

Keckley's dedication to her craft is evident in her own words: "I would rather work my fingers to the bone, bend over my sewing till the film of blindness gathers in my eyes," she expressed, highlighting her relentless pursuit of financial stability to support her family (Keckley, 45). Through perseverance, she eventually purchased not only her own freedom but also that of her sons, paying a sum of $1200 to her master (Keckley, 49). Her clientele predominantly consisted of white women, for whom she crafted dresses,allowing her the connections to get profit. Scholars delve into Keckley's economic worth and its reflection on her social standing, emphasizing how her labor empowered her to strategize her path to freedom (Janaka Lewis). By valuing herself in economic terms and strategically planning her liberation, Keckley challenged the oppressive system that confined her. She recognized the potential to leverage her labor as a tool for personal advancement, ultimately achieving not only freedom but also a sense of fulfillment in the process.

While Elizabeth Keckley's journey represents a story of triumph within the economic and societal constructs of her time, the experiences of other enslaved women varied. Many had to seek fulfillment and self-expression through alternative means, which may not have been as documented or celebrated.

Control Through Clothes and the Body

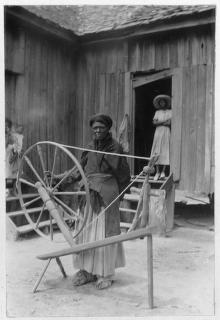

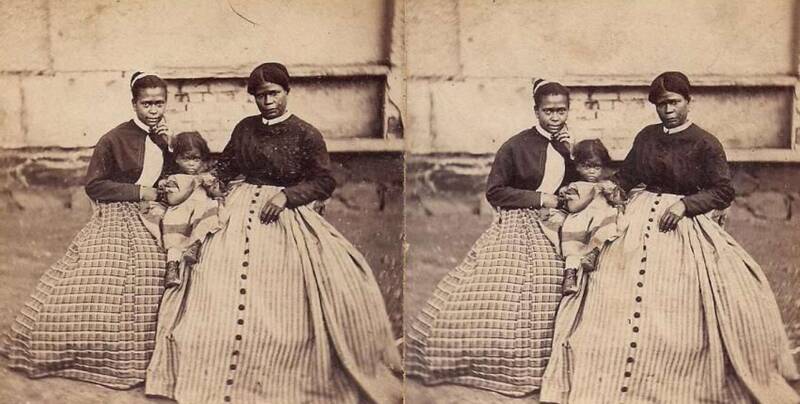

Although enslaved individuals could not attain physical freedom, they found solace in their imagination and what Stephanie Camp refers to as the "second body." Much of their identity was expressed through their clothing, which was heavily controlled. As seen above, the image of the woman in her daily work clothes. Slavery imposed restrictions even on attire, with owners obligated to provide slaves with either two changes of clothing per year or a set amount of cloth (Weaver, 47). This clothing, however, was typically obtained with minimal effort, leaving enslaved women devoid of personhood. Planters reinforced the status of enslaved individuals by dressing them in the lowest quality garments, symbolizing their bondage (Camp, 559).

Poor investment in their clothing reaffirmed the dehumanization of bondspeople. These garments, often termed as "Negro cloth," were made from coarse and inexpensive materials, symbolizing the minimal effort slave owners put into clothing their laborers. This lack of investment served as a constant reminder of the slaves' inferior status. Additionally, colonists with limited resources would resort to using homespun linen, cotton, or wool cloths.

Furthermore, some planters distributed clothing with dramatic flair, aiming to portray themselves as benevolent providers of care and sustenance, thereby instilling loyalty in their bondspeople (Camp, 559). The planters aimed to present the act of providing clothing as a grand gesture of service, yet it merely met the basic human need for attire. Often, however, these gestures fell short, leaving many slaves unclothed.

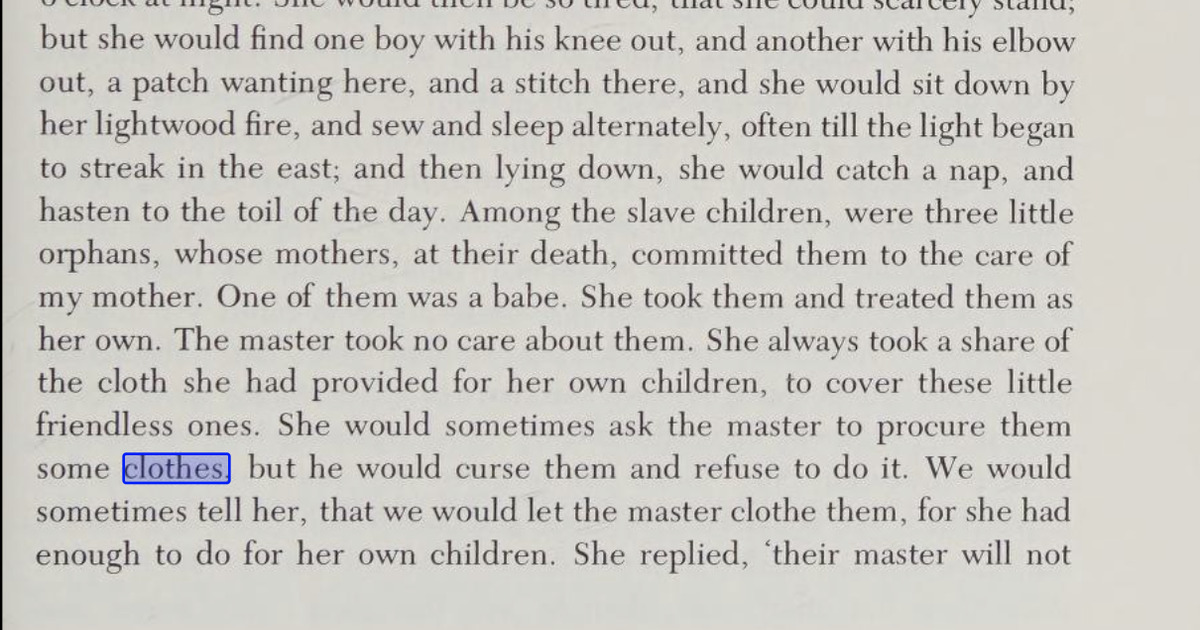

It was the responsibility and agency of black women to reclaim personhood and humanity through clothing. One slave testimony illustrates how women took it upon themselves not only to dress themselves and their own children but also to provide clothing for orphaned and destitute children. This act was a profound assertion of humanity and a struggle for dignity.

Dreaming Freedom

While much of black women’s and other enslaved individuals' personhood was compromised, this did not stop enslaved women from dreaming about freedom – freedom from the body. In Stephanie Camp’s Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South, the chapter "The Intoxication of Pleasurable Amusement," discusses the ways in which women coped with life on the plantation, their second shift of labor. The enslaved women's second shift of labor presented an opportunity for self-expression. After toiling in the plantation fields, they would return home to work on their families. Once they had acquired fabric, "enslaved women went to great efforts to make themselves more than the cheap, straight-cut dresses they were allowed" (Camp, 82). They would incorporate patterns such as stripes, polka dots, and colors into them. The images reflect the skill of sewing ad the way in which these recontructions may have looked.

Moreover, they dreamed of the lifestyle their white owners enjoyed. They fantasized about this way of life, and through their adornment, they expressed the need for freedom. For example, the essence of the skirts was in fashion in the 1850s and stayed in style through the mid-nineteenth century, coinciding with the cult of domesticity (Camp, 83). However, this domesticity can also be seen through black women’s important role as domestic laborers; they were essentially the creators of domesticity, but it was white women who claimed it. The skirts represented Victorian ideals of respectable womanhood (Camp, 83), but they were also a form of resistance. Enslaved women liked to conceptualize their dress to embody abundance, through their huge hoop skirts. As Camp puts it, they worked hard to "make their bodies spaces of personal expression and pleasure," using dress to push against the view of them as "joyless drudges" (Camp, 83). They rejected subjugation and made space for something opposite of a constrained body.

In other examples, there were house slaves who dreamed and fantasized about their freedom by outwardly just using their owners' things. In To Joy My Freedom, Tera Hunter tells the story of Ellen, a house slave, who would steal her mistress's toiletries and would indulge in this pleasure, dreaming of "a life that could be soon within her reach" (Hunter, 5). These rituals that 'minted to enhance white bodies only' were not a limitation to black women in dreaming for themselves. They would achieve this and more.

Fashioning Freedom

For those who were on the brink of freedom during the Civil War era and post-emancipation, this signified the establishment of a new standard of life. This newfound freedom meant distinguishing between work and leisure, not conflating the two, and continuing to attribute value to their personhood beyond their occupation. In To Joy My Freedom, Hunter explains that freed women took pride in their appearance. Many women continued to work in roles such as seamstresses, which provided them with a degree of autonomy. As noted in the story of Elizabeth Keckley, this autonomy was particularly pronounced for those with the highest skills, as it offered greater financial reward, creative fulfillment, and enjoyment. This emphasis on formal skill development represented an effort to educate women formally in becoming seamstresses.

Furthermore, for others, the freedom expressed through clothing served as a reaffirmation of their newfound liberties. Despite facing criticism for their colorful attire and self-assured demeanor, which was often dismissed as "uppity" by white society (Hunter, 2), black women embraced these expressions as a means of reclaiming their dignity and humanity. This defiance represented a rejection of the dehumanization they endured for centuries. By asserting themselves through their clothing and demeanor, they were not only reclaiming their time but also affirming their intrinsic worth and reclaiming their humanity. Clothes were a statement that sickened white folk, but it was a new reality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the exploration of black women's relationship with fashion within the confines of enslavement reveals a complex interplay of self-expression, resilience, and the pursuit of freedom. Despite facing severe limitations on their labor, time, and autonomy, enslaved women demonstrated resourcefulness in using clothing and adornment as a means of asserting their identity and reclaiming their humanity. Through the skilled labor of individuals like Elizabeth Keckley, who leveraged her talent as a seamstress to secure her freedom, we witness stories of determination perseverance. Moreover, the act of adorning oneself was not merely a superficial pursuit but a profound assertion of personhood and dignity.

Enslaved women sought to transcend their circumstances by imbuing their clothing with meaning, whether through subtle modifications or bold expressions of resistance. These acts of self-expression served as a form of resistance against the dehumanizing forces of slavery, allowing women to assert agency and cultivate a sense of individuality.

As we reflect on the legacy of black women's fashion in the plantation South, it is essential to recognize the enduring significance of their contributions. By reclaiming control over their bodies and their attire, enslaved women paved the way for a more inclusive vision of freedom. Their stories serve as a testament to the power of self-expression and the enduring spirit of resistance in the face of oppression.

Works Cited

Blassingame, John W. Slave Testimony : Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976.

Camp, Stephanie. 2004. “The Intoxication of Pleasurable Amusement: Secret Parties and the Politics of the Body.” In Closer to Freedom Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Camp, Stephanie M. H. 2002. “The Pleasures of Resistance: Enslaved Women and Body Politics in the Plantation South, 1830-1861.” The Journal of Southern History 68 (3): 533. https://doi.org/10.2307/3070158.

Weaver, Karol K. 2012. “Fashioning Freedom: Slave Seamstresses in the Atlantic World.” Journal of Women’s History 24 (1): 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2012.0009.

![[Four African American women seated on steps of building at Atlanta University, Georgia]](https://course-exhibits.library.dartmouth.edu/files/large/c9527e5f656508b23e6957b4f8853c95396507a3.jpg)