Reproductive Labor and Resistance of Enslaved Women in the Antebellum South: Stories of Mary Gaffney and Women Like Her

Antebellum South post-Atlantic Slave Trade

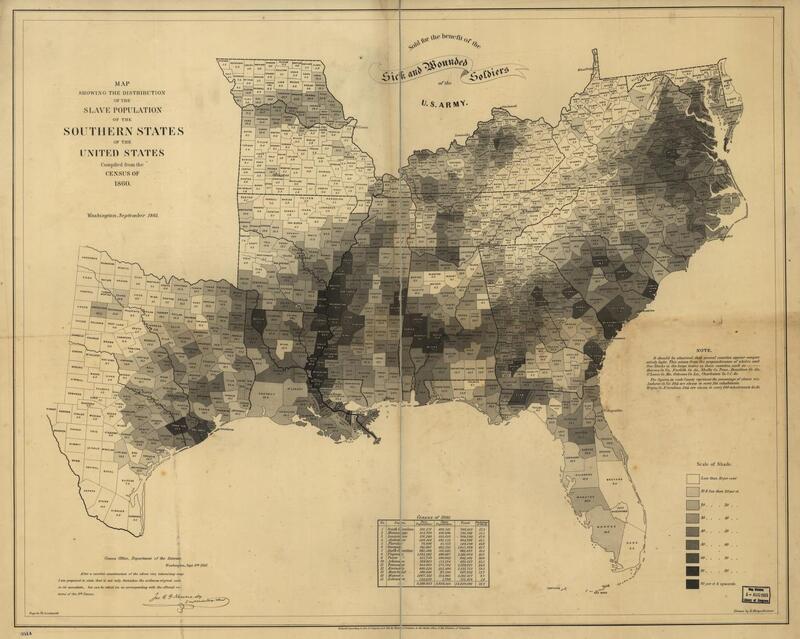

After the atlantic slave trade had ended in 1808, the antebellum south had became the primary location of slavery within the United States. With the economic incentive of cotton, and cuttoff from an external source of slaves, there became a widespread focus on increasing the slave population already in the United States. Although reproductive labor had long been a focus of chattel slavery within the U.S. this increased emphasis resulted in a population boom that can be observed through population statistics from this period. A research article looking into the growth of slave population within the United States places the enslaved birth rate for the U.S. during the antebellum period was 55.1 per thousand (Hacker).

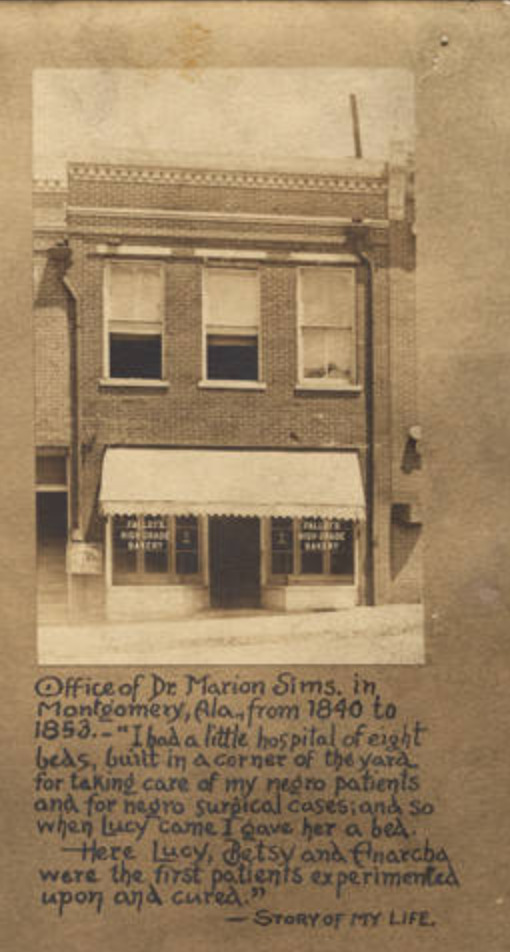

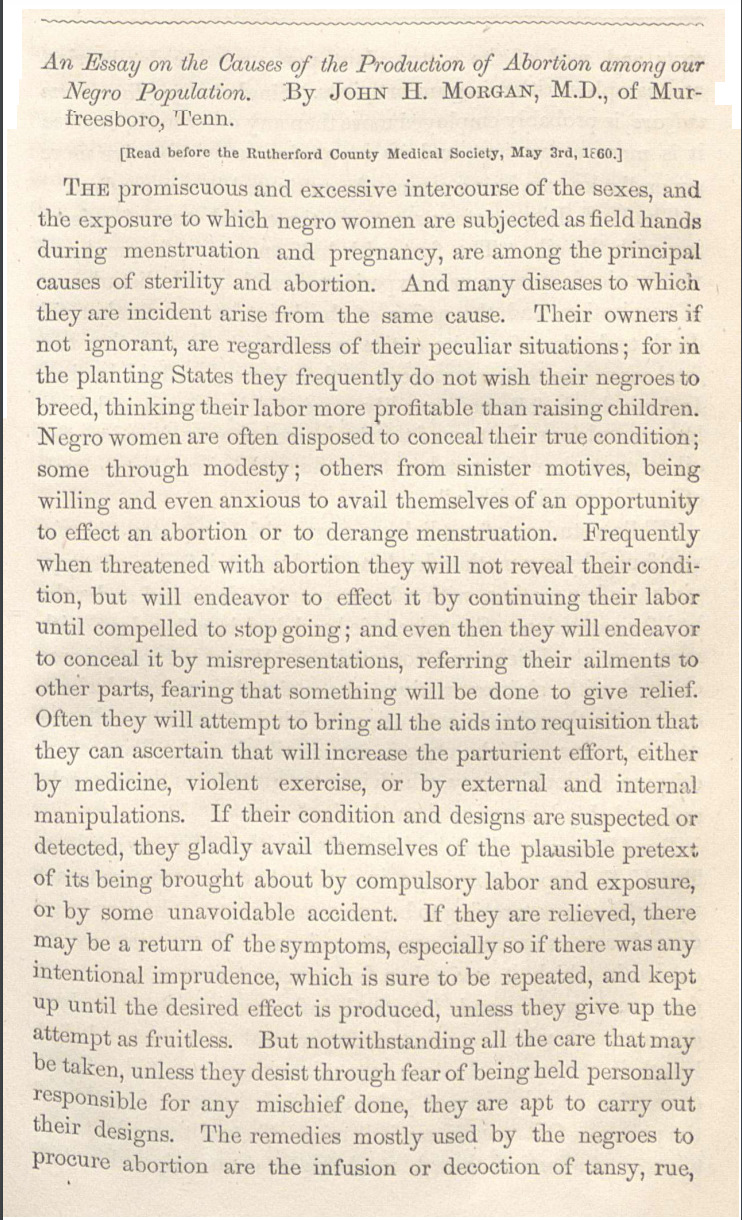

It is also estimated that among the estimated 9.3 million slaves that were born between 1620 and 1865, 5.6 million occured after 1830 (Hacker). The map below was created from census data from 1860, a year before the civil war began. This increase in US-born slaves was a result of a focus on the reproductive labor of enslaved women, this was done through means of coercion, rape, or other methods designed to strip away the autonomy of black women. The focus on reproductive labor for enslaved women in antebellum south created moments in which enslaved women, motivated by the desire to not have their children grow up in slavery, engaged in moments reproductive resistance such as the use of abortifacients or infanticide.

"I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?"

-Sojourner Truth, Delivered 1851 at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio

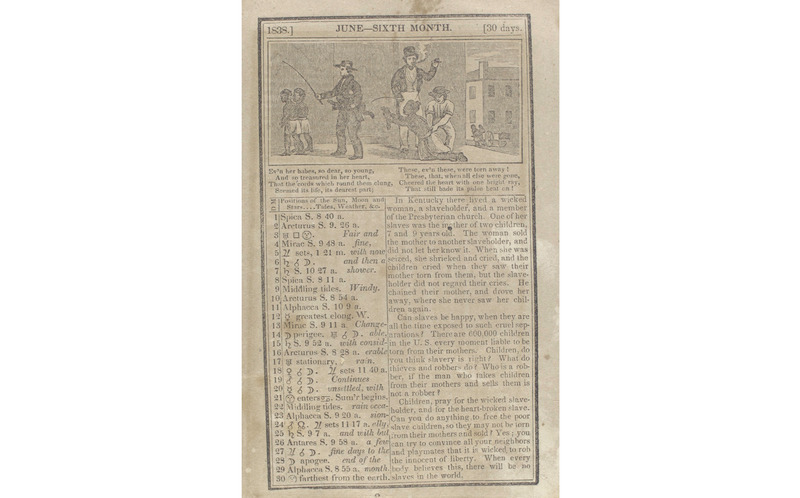

“When she was seized, she shrieked and cried, and the children cried when they saw their mother torn from them, but the slaveholder did not regard their cries. He chained their mother, and drove her away, where she never saw her children again."

Keckley, E. (1868). Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (p. 49). G.W. Carleton & Co. "...for I could not bear the thought of bringing children into slavery--of adding one single recruit to the millions bound to hopeless servitude, fettered and shackled with chains stronger and heavier than manacles of iron."

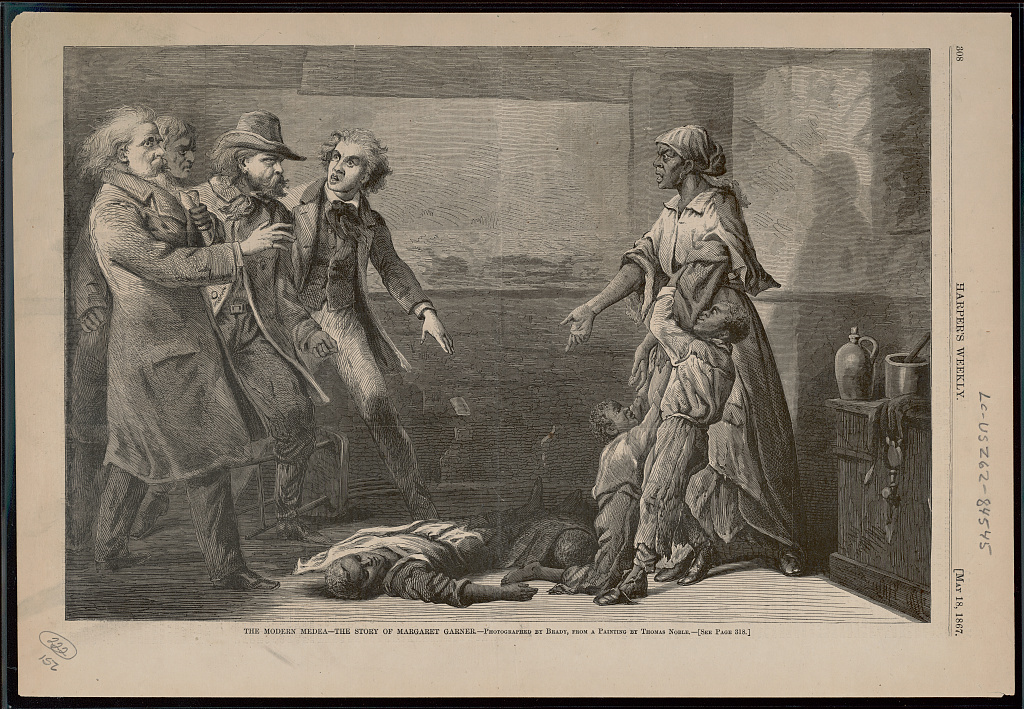

“Mother, I will kill my children before they shall be taken back, every one of them." (New York Times, “The Slave Tragedy in Cincinnati,” February 2, 1856)

Margaret Garner

"Well you have sold calves from cows haven't you? and heard them bawl for 3 or 4 days for their calves, that was just the way with the slaves."

Mary Gaffney (George Rawick, “The American Slave: Supplement Series 2, Volume 5: Texas Narratives, Part 4”, (Greenwood Press, 1979))

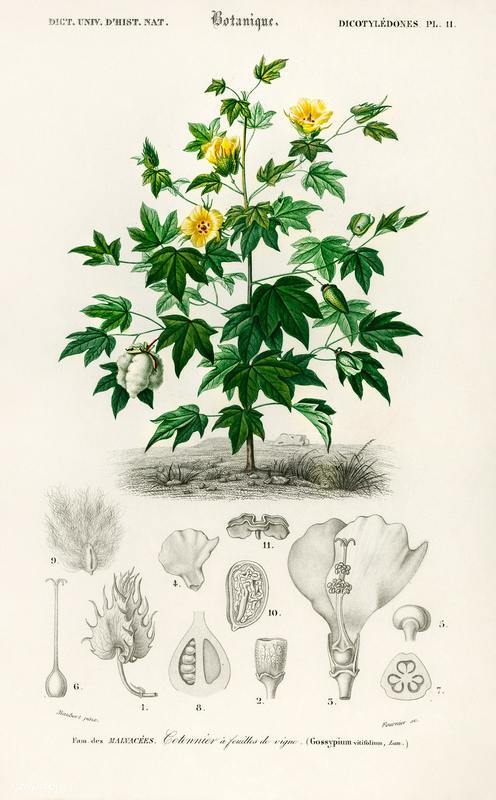

"He put another negro man with my mother, then he put one with me. I would not let that negro touch me and he told Maser and Maser gave me a real good whipping, so that night I let that negro have his way. Maser was going to raise him a lot more slaves, but still I cheated Maser, I never did have any slaves to grow and Maser he wondered what was the matter. I tell you son, I kept cotton roots and chewed them all the time but I was careful not to let Maser know or catch me, so I never did have any children while I was a slave."

Mary Gaffney (George Rawick, “The American Slave: Supplement Series 2, Volume 5: Texas Narratives, Part 4”, (Greenwood Press, 1979))

"I have known too of women that got pregnant and didn't want [sic] the baby and the unfixed themselves by taking calomel and turpentine. In them days the turpentine was strong and ten or twelve drops would miscarry you. But the makers found what it was used for and they changed the way of making turpentine. It ain't no good no more. They used to take indigo to unfix themselves."

Lu Lee, Rawick, The American Slave, Supplement Series 2, Vol. 6. Texas Narratives, Pt 5 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1979), 2299.

"The few references to contraceptives or abortifacients in Afro-American and Caribbean sources support the notion that women and men transferred knowledge of fertility control from Africa to the Americas. (Morgan, 113) Along with the abortifacients described above (cotton

- Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle "we take the language and the physicality of geography seriously... so that black lives and black histories can be conceptualized and talked about in new ways." (McKittrick, 13)

Through this collective I hoped to have created a larger historical context through which we can view reproductive justice while also exploring what these acts of resistance meant in terms of how maternity/reproduction was valued for enslaved black women and the gendered violence endured because of it. Reproductive justice/women’s health as we know it today is deeply rooted in the pain and resistance of enslaved black women, as people who had to take back their autonomy over their reproductive systems. In many cases in which reproductive health has been endangered, one primary example being the overturning of Roe v. Wade, it is primarily black women, also in rural communities like those in the south, that bear the brunt of negative associated outcomes. By collecting first hand accounts we not only breathe new life into these stories but also combat the negative stereotypes about black women that still persist to this day.

It's important that we view any action of reproductive resistance taken by enslaved women through the eyes and lense of their situation. Although it may be easy to judge within the standards of our own moral complexity or standards, the extreme and often psychologically scarring situations in which the lack of autonomy slavery was built upon didn't allow for many other options. Through the analysis of these stories and connecting them to other frameworks of analysis and guided histories not only do we breathe new life into these stories but we respect these women as individual actors who displayed resistance in impossible situations and above all else prioritized autonomy and life above all else through aw-inspiring acts of bravery.