Lexi C

Flora Stewart

-

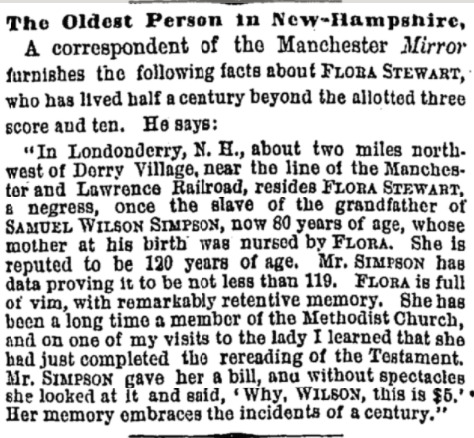

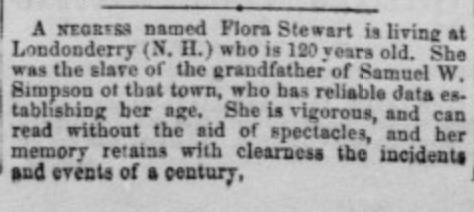

Flora Stewart was born a slave in Londonderry, New Hampshire with a family of the last name of Wilson. Flora lived for several years in Candia as a slave for William Duncan who was a trader. She eventually married a colored man with the last name Stewart and had two sons with him. Around 1835, Flora left Candia and returned to Londonderry. Flora was liberated from slavery around 1815. On May 19th, 1867, The New York Times published a piece titled: “The Oldest Person in New Hampshire,” her position as an enslaved woman is described, as well as her age, and her sharp memory. A correspondent of the Manchester Mirror said when talking about Flora: “Her memory embraces the incidents of a century,” – highlighting the public acknowledgement of the tumultuous and stressful past Flora had as a slave, but the lack of detail regarding what exactly her memory held and what ‘incidents’ he was referring to, demonstrates a lack of knowledge and understand of what it meant to be an enslaved woman during this time period. Flora died in Londonderry, New Hampshire in 1868 and was buried in the Valley Cemetery.

-

The origin of this photo stems from Flora’s uniqueness and “a few years before she passed away she was brought to Manchester by John D. Patterson of that place and a photograph was taken of her form and features,” (Moore et al., 1893, p. 459)(Nutfield Genealogy). This exemplifies the dehumanization of Black women at the time that currently exists to this day, as she was recognized not for her life story and the experiences she lived through, but for her age, her form, and her features. “Though the justification for her photograph is a reminder of the dominant societal perception of black people, Flora through this picture established her humanity, captivated the attention and mind of viewers,” (nypl.org). Her photo tells a story, and this can be inferred through her clothing, her facial expression, and the presence of a cane. Her clothing is seemingly expensive, as it includes drapery, ruffles, and fine detailing. The dark color of her dress and coat exudes a somber mood yet cements her reputation as a refined woman, deserving of recognition and respect. Additionally, “during that period of the 19th century, attire was associated with class, and members of the upper class wore rich fabric, and shimmering silk signaled a tasteful affluence (Wardrop, 2009). Flora positioned herself by the way of dress as a citizen and, more importantly, as a woman with respect and dignity,” (nypl.org). The cane that is present in her right hand serves as an embodiment of her age, causing viewers to reflect upon the time that she has lived and the variety of experiences she has undergone – both positive and negative. Despite her age, she sits upright – signifying strength. The white collaring surrounding her face, draws viewers to gaze more closely at her expression. Her expression is quite solemn and unamused, and though this might be a stylistic choice from the photographer, it may also suggest her feelings towards the request of her photograph and the dehumanization that was tied to it. Varying narratives of whether or not a “happy” enslaved person truly ever existed, but this depiction of Flora and the absence of a smile causes viewers to ponder the struggles and trauma that she was subjected to as an enslaved woman. Though the reasoning behind her photograph is troubling, her presence and the way she is remembered and upheld throughout history represents resilience, strength, and power.

-

From the information that is available on Flora Stewart and her life, an overarching theme is the attention to her status as a previously enslaved woman, her age, her religion, and her place of living. The piece titled “The Oldest Person in New Hampshire,” references her allegiance to God, saying: “She has been a long time member of the Methodist Church, and on one of my visits to the lady I learned that she had just completed the rereading of the Testament,”(nypl.org).

-

The Sacramento Daily Union calls Flora “vigorous,” explaining that she “can read without the aid of spectacles, and her memory retains; with clearness the incidents and events of a century,”.

-

The reoccuring information that is shared by varying news sources reveals that they were purely interested in surface level information regarding Stewart’s life and the ‘incidents and events’ that she endured in her lifetime. If a white person during this time period lived to be 118, it’s quite possible that there would be more information and in-depth interviews regarding the life that they lived.

Enslaved Women in Hanover, New Hampshire

Betty

-

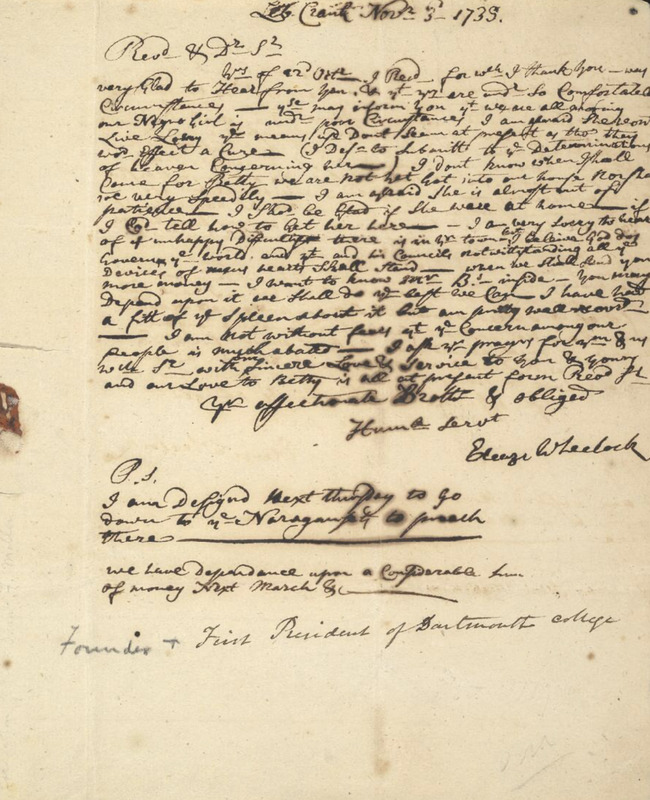

“Our Negro girl is under poor circumstances I am afraid she won’t live long...I don’t know when I shall come for Betty... I should be glad if she were at home, if I could tell how to get her here... Our love to Betty is all at present form,” (Dartmouth Digital Collections)

-

These quotes provide information that allows us to understand that Betty was an enslaved woman, presumably young as she is referred to as a “girl,” instead of a “woman,” and that she was in critical condition and suffering from poor health. Wheelock writes saying that he wants Betty home, and that he and his family have love for Betty, which is a sentiment rarely expressed in Wheelock’s letters regarding his enslaved persons. This could be telling of a strong and friendly relationship that Betty had with Wheelock’s family or could just be an example of Wheelock sending well wishes to his enslaved person that was in extremely poor condition.

Dinah

-

“Do sell, convey, confirm and deliver unto him the said Wheelock his heirs & assigns, one certain Negro woman named Dinah aged about twenty years to have and hold said Negro woman as a servant for life,” (Dartmouth Digital Collections)

-

Dinah was sold to Eleazar Wheelock in 1769 by his son-in-law Alexander Phelps for the price of £50.

-

There is very little information about Dinah, such as what work she did under Wheelock, her date of death, her state of being, etc. The quote regarding her sale is dehumanizing and portrays her as an object and piece of property.

Selinda and Anna

-

In Eleazar Wheelock’s will he writes to his son John Wheelock saying: “I give him… rights to my servants,” (Dartmouth Digital Collections)

-

In this letter he grants freedom to an enslaved man named Archelaus when he reaches the age of 25, but this same courtesy is not extended to Selinda and Anna.

-

Wheelock granting Archelaus freedom, but not Selinda and Anna causes individuals to question the work that these enslaved women were doing for him, and whether or not their servitude had an ending date or if it was indefinite.

Chloe

-

Chloe was an enslaved woman sold to Eleazar by Ann Morison in 1762, along with her husband Exeter and her son Hercules. In a 1765 recommendation “Chloe is praised as ‘good tempered’ with an admirable understanding of ‘women’s business’ which could mean anything from cooking and cleaning to sewing and midwifery,” (Dartmouth & Slavery Project). In 1768, Wheelock acknowledged Chloe’s profession of faith. It’s also revealed that Chloe was abused extensively by her husband Exeter. Warrants and letters confirm that at some point Chloe was freed.

-

Chloe appears to have the most information available on her as an enslaved woman who lived and worked in Hanover, New Hampshire. The fact that she was sold together with her son and husband seems to be fortunate and rare. The way she is described reveals that she is a valuable slave, as she performed her work well. She also seems to be one of the few female slaves from Hanover that achieved freedom.

Analysis of Enslaved Women in Hanover

-

The information that is available regarding enslaved women often captures who they were enslaved under, the type of work they carried out, and a report of their health. These women very rarely have information such as last names, the length of their slavery sentence (as many had life sentences), who their family members were, birth/death dates, etc. Many of these women only exist in historical archives due to their names being briefly mentioned in letters in reference to their servitude.

Differences and Similarities between Flora Stewart and Women Enslaved in Hanover, New Hampshire

- Due to the lack of information on both Flora Stewart and the women who were enslaved in Hanover, it is unclear the amount of similarities and differences that truly exist between the two. Based on the information that is available for both, it is evident that these women were not truly recognized for who they were as a person, but what they had to offer to society. Flora Stewart was published about, as entertainment for those who read newspapers – and the pieces mainly focused on her age, as that was something that was seen as extremely interesting. The information that is available about enslaved women in New Hampshire comes from letters and Eleazar Wheelock’s will, a stark difference from the information available about Flora. The fact that prior to the creation of the Dartmouth and Slavery Project, there was no published information about the existence of these enslaved women reveals the importance that they had in Hanover, New Hampshire at the time. The times that they were mentioned in documents were never intended to be read by large audiences or be available as an archival resource at Rauner Library. If these letters and documents were never recovered, this would have resulted in the erasure of these women from history. Additionally, their mentioning in letters strictly pertained to their functioning and status as a slave. Both cases highlight the way that Black women during the 17th, 18th, and 19th century were only valued when they were able to be used. Though there is vastly more publications and information surrounding the life of Flora Stewart, a key aspect of her life and her story is missing – that being her own words and the telling of her experiences. Despite the fact that several newspapers published pieces about her and that she was taken to Manchester, New Hampshire to get her photo taken, none of these sources used this opportunity to interview her – demonstrating a lack of interest and care about the life she had lived.

Sources:

Alex. Phelps, Bill of Sale, to Eleazar Wheelock, 1769 January 30, collections.dartmouth.edu/teitexts/edwc/diplomatic/769130_1-diplomatic.html. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

“Chloe.” Dartmouth Libraries, Dartmouth & Slavery Project, 12 Sept. 2023, www.library.dartmouth.edu/slavery-project/biographies/enslaved/chloe.

“Considering Flora Stewart’s Portrait as an Autobiography of an African American Woman.” The New York Public Library, www.nypl.org/blog/2020/06/09/flora-stewarts-portrait-autobiography. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Eleazar Wheelock, Letter to Stephen Williams, 1735 November 3, collections.dartmouth.edu/teitexts/edwc/diplomatic/735603-diplomatic.html. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Eleazar Wheelock, Will, 2 April 1779, collections.dartmouth.edu/teitexts/edwc/normalized/779252-5_779354-1-normalized.html. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

“Flora Stewart: African American Woman, Oldest Citizen of Londonderry, N.H.” The New York Public Library, www.nypl.org/blog/2020/06/04/flora-stewart-londonderry-nh. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Rojo, Heather Wilkinson. “Flora Stewart - Black History Month in Londonderry.” Nutfield Genealogy, nutfieldgenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/02/flora-stewart-black-history-month-in.html. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.