Lauren L

My mammy’s name was Harriet Clemens. When I was too little to know anything ’bout it she run off an’ lef’ us. I don’t ’member much ’bout her ’fore she run off, I reckon I was mos’ too little. She tol’ me when she come after us, after de war was over, all ’bout why she had to run away: It was on ’count o’ de Nigger overseers. (Dey had Niggers over de hoers an’ white mens over de plow han’s.) Dey kep’ a-tryin’ to mess ’roun’ wid her an’ she wouldn’ have nothin’ to do wid ’em. One time while she was in de fiel’ de overseer asked her to go over to de woods wid him an’ she said, “All right, I’ll go find a nice place an’ wait.” She jus’ kep’ a-goin. She swum de river an’ run away. She slipped back onct or twict at night to see us, but dat was all.

ANNA BAKER, enslaved in Alabama

One woman name Rhodie runs off for long spell. De hounds won’t hunt her. She steals hot light bread when dey puts it in de window to cool, and lives on dat. She told my mammy how to keep de hounds from followin’ you is to take black pepper and put it in you socks and run without you shoes. It make de hounds sneeze.

WALTER RIMM, enslaved in Texas

Slaves would run away but most of the time they were caught. The Master would put blood hounds on their trail, and sometimes the slave would kill the blood hound and make his escape. If a slave once tried to run away and was caught, he would be whipped almost to death, and from then on if he was sent any place they would chain their meanest blood hound to him.

OCTAVIA GEORGE, enslaved in Louisiana

One of de slaves married a young gal, and dey put her in de “Big House” to wuk. One day Mistess jumped on her ’bout something and de gal hit her back. Mistess said she wuz goin’ to have Marster put her in de stock and beat her when he come home. When de gal went to de field and told her husband ’bout it, he told her whar to go and stay ’til he got dar. Dat night he took his supper to her. He carried her to a cave and hauled pine straw and put in dar for her to sleep on. He fixed dat cave up just lak a house for her, put a stove in dar and run de pipe out through de ground into a swamp. Everybody always wondered how he fixed dat pipe, course dey didn’t cook on it ’til night when nobody could see de smoke. He ceiled de house wid pine logs, made beds and tables out of pine poles, and dey lived in dis cave seven years. Durin’ dis time, dey had three chillun. Nobody wuz wid her when dese chillun wuz born but her husband. He waited on her wid each chile. De chillun didn’t wear no clothes ’cept a piece tied ’round deir waists. Dey wuz just as hairy as wild people, and dey wuz wild. When dey come out of dat cave dey would run everytime dey seed a pusson. De seven years she lived in de cave, diffunt folks helped keep ’em in food. Her husband would take it to a certain place and she would go and git it. People had passed over dis cave ever so many times, but nobody knowed dese folks wuz livin’ dar. Our Marster didn’t know whar she wuz, and it was freedom ’fore she come out of dat cave for good.

LEAH GARRETT, enslaved in Georgia

Everyday acts of resistance represent subtle yet powerful means through which slaves asserted their defiance and autonomy. Camp emphasizes the significance of these "small acts with outsize consequences" which, despite appearing minor, held immense significance in allowing slaves to reclaim control over their lives. The act of ‘absconding’ (running away) is one strategy that afforded slaves some degree of freedom that directly challenged the authority of their masters. Traditional historiographies have often focused on male runaway slaves, sidelining the contributions of Black women. This digital archive aims to bridge this gap by examining the leadership and involvement of Black women escaping slavery in Charleston, South Carolina from the 1830s to 1850s. Through runaway advertisements and slave narratives, this archive sheds light on the untold stories of Black women and showcases their crucial role in resisting slavery and patriarchal oppression.

As North America's largest port of entry, Charleston served as a hub for runaway slaves across the Deep South. Leveraging the city's significant 73% Black population, runaways could “blend in among the crowds of black women in the streets, seek refuge with family and friends, and secure casual employment to support themselves, enabling many to evade capture” (Marshall, 2014, 191). The city's diverse population attracted “women from Georgia and up-country South Carolina as well as from along the South Santee, Ashepoo, and Cooper Rivers” (Marshall, 2014, 191) further contributing to its appeal as a sanctuary for runaway slaves.

The Charleston Courier, the daily newspaper of Charleston in the mid-1800s, provides an archival record of societal events and developments, including runaway slave advertisements. The newspaper's documentation of runaway slave ads not only sheds light on individual escape attempts but also provides broader context for understanding the dynamics of slavery and resistance in Charleston and the surrounding areas. The Courier's reports of slaves supposed to be “lurking about the city, where every facility of concealment is offered” (Marshall, 2014, 192) suggests the city's geography, social structures, and community support networks ultimately facilitated the evasion of capture. Charleston's status as a major port city with a significant Black population, coupled with coverage provided by the Courier, makes it a particularly intriguing and valuable location for the study of runaway slaves.

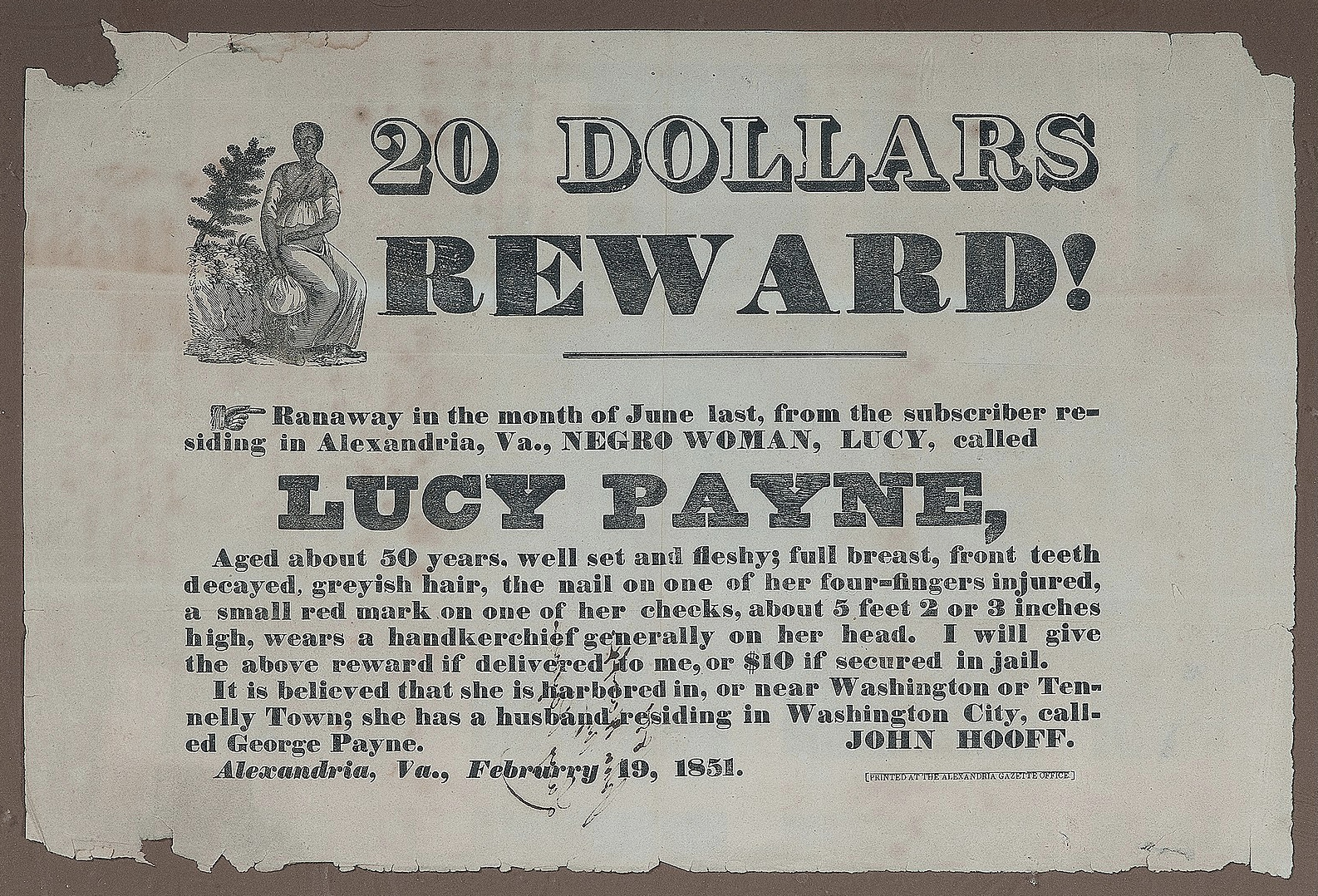

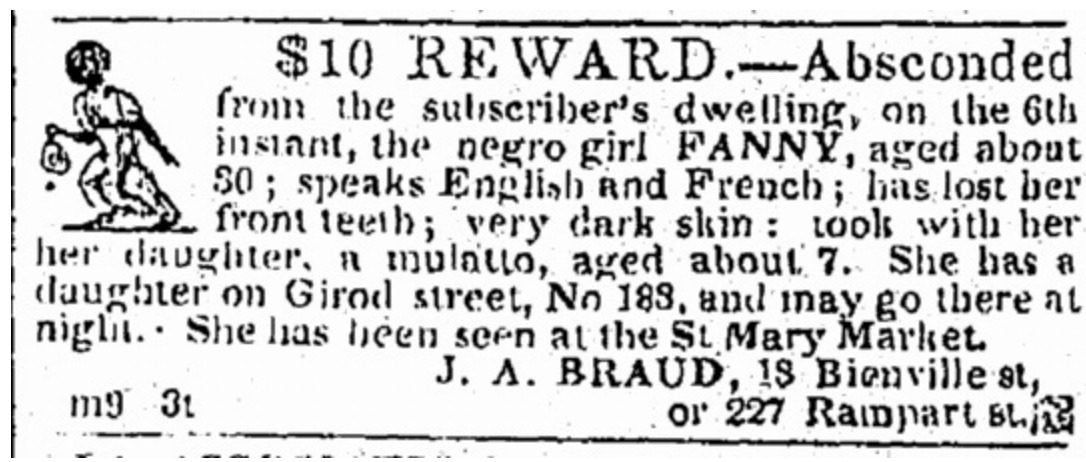

Slave advertisements in the Courier described age and physical characteristics, and offered a monetary reward upon capture. By reading along the bias grain, these archival fragments also reveal insights into the intentions and motivations of the runaways. Runaway ads uncover the significant influence that kinship and family connections had on the motivations behind fleeing and where fugitives chose to go. The ad for 18-year-old Hester, for example, reveals her desire to reunite with her mother: “She has since attempted to make her way to Charleston, to her mother, who lives there.” Similarly, Fanny’s ad mentions that she “took with her her daughter, a mulatto, aged about 7. She has a daughter on Girod Street, No. 188, and may go there at night.” Lucy’s ad mentions that “she is likely being harbored in or near Tennelly Town or Washing City, where her husband Goerge Payne resides.” Compared to single young men who often ventured North solo, most women who ran away preferred to stay within the state, likely to remain near their families, husbands, and children who might still be enslaved. Anna Baker's recollection about mother in her slave narrative further illustrates this dilemma: “She tol’ me when she come after us, after de war was over. She slipped back onct or twict at night to see us, but dat was all.” These early memories suggest that Anna’s mother might’ve grappled with two conflicting desires: to seek freedom for herself and to be with her family, as evidenced by her attempts to slip back and visit. Anna Baker later reflects that she understood her mother and recognized the added risk involved in attempting to escape with her when she was a young child (“I reckon I was mos’ too little to know anything”). These reflections shed light on the complex considerations and challenges faced by enslaved Black women when contemplating escape.

Anna Baker and Leah’s slave narratives provide further insights on the motivations driving runaway slaves, albeit not from their personal experiences but from the stories they've heard. Anna remembers that her mother told her “all ’bout why she had to run away: It was on ’count o’ de Nigger overseers. Dey kep’ a-tryin’ to mess ’roun’ wid her an’ she wouldn’ have nothin’ to do wid ’em.” Her mother's escape reveals a strong motivation rooted in resisting sexual harassment and abuse by overseers. This recollection highlights the pervasive threat of violence and exploitation faced by enslaved women on a daily basis that compelled them to flee for their safety and dignity. Similarly, Leah recounts a situation where a young woman faced severe punishment for defending herself against her mistress: “One day Mistess jumped on her ’bout something and de gal hit her back. Mistess said she wuz goin’ to have Marster put her in de stock and beat her when he come home. When de gal went to de field and told her husband ’bout it, he told her whar to go and stay ’til he got dar. ” Leah’s narrative shows how both anger and bravery prompted the woman to take risks in resisting punishment, refusing brutality and seeking refuge. An interplay of factors, from resistance of exploitation to the desire for autonomy and safety, motivated enslaved individuals to undertake the risk of escape.

Diving further into Leah’s narrative, the story of the runaway slave who hid in a cave for seven years, isolated from society, highlights the lengths to which women would go to evade capture and live independently. “People had passed over dis cave ever so many times, but nobody knowed dese folks wuz livin’ dar. When dey come out of dat cave dey would run everytime dey seed a pusson. Our Marster didn’t know whar she wuz, and it was freedom ’fore she come out of dat cave for good.” The fear of detection was so intense that she would flee at the sight of any person and practice constant vigilance to remain undetected. This narrative illustrates the resilience, resourcefulness, and determination of fugitive women, even in the face of extreme hardship and isolation.

Leah’s story also highlights how supportive communities played a crucial role in aiding runaway slaves and served as a lifeline for their survival. Leah mentions how various individuals contributed to the collective effort of providing food for the runaway slave girl over a long time: “De seven years she lived in de cave, diffunt folks helped keep ’em in food.” These networks of support were not only crucial in providing basic necessities like food, but also in ensuring the safety and well-being of fugitives.

Slave mothers and women played a vital role in aiding runaway slaves and fostering this culture of empathy and protection within slave communities. Sorensen notes, “By example, slave women taught their children the rules for helping fugitives and those for being a fugitive; keeping one’s mouth shut around whites, being prepared to share food with fugitive slaves, and watching for the best chance to run.” Slave women led with their actions, teaching their children essential principles for assisting fugitives and surviving as runaways. The leadership of slave mothers and women in imparting this knowledge underscores the significance of maternal guidance in shaping attitudes towards empathy and communal support. Black women’s leadership in these networks were integral to the efforts of runaway slaves and within slave communities to teach by example how to be resilient within the confines of slavery.

Runaway slave advertisements further reveal the context of danger involved for harboring and helping fugitives. Viletta, Mary, and Joan's ads not only describe the efforts to locate and retrieve escaped slaves, but also issue warnings and threats of punishment for those found harboring them: “Masters of vessels and others, are cautioned against harboring said negro, as the law will be enforced against those who violate it” and “A further reward of Twenty Dollars will also be given for proof of her being harbored by any person whatever.” These networks of support persisted in the face of dangers, which were outlined in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 ($1000 penalty on any person and jailtime who helped harbor or conceal escapees). Both the runaway women and the supportive communities needed resilience and courage to confront the fear of risk associated with resisting slavery.

Not only did the communities of support assist the slaves, but the narratives of slave women escaping also profoundly influenced the communities themselves. The women who successfully ran away became legends to the communities and fostered inspiration and hope. Octavia's account remembers how slaves retaliated against their pursuers by killing bloodhounds: “The Master would put blood hounds on their trail, and sometimes the slave would kill the blood hound and make his escape.” These acts of defiance are celebrated within the community and fosters a sense of empowerment. Walter's quote highlights Rhodie’s ability to outwit the bloodhounds and sustain herself by stealing food: “One woman name Rhodie runs off for long spell. De hounds won’t hunt her. She steals hot light bread when dey puts it in de window to cool, and lives on dat.” By recounting runaway stories, Walter and Octavia not only immortalize the runaways’ courage, but also reinforces a spirit of collective resistance and resilience among the community. Stories about others being brave can serve as powerful examples of courage in action and instill confidence and optimism. By listening to the runaway stories of others, enslaved individuals may draw strength, motivation, and encouragement to be brave in their own lives. These runaway stories serve as reminders that freedom is possible and as powerful symbols of courage and determination that inspire hope and solidarity among enslaved communities.

From these quotes, there is a sense of praise and admiration for those who braved risk of punishment to challenge the laws of slavery. Sorensen writes how “Recognizing and then acting on the urge to run, making a personal decision, whether to the North or the next plantation, constituted a specific statement about the value and meaning of freedom to a slave. They had learned from the women around them as they grew to adulthood that running away was an option, a choice, a statement of courage and devotion.” Sorensen captures how mothers and women empowered their children and communities to foster a sense of agency in creating one’s own meaning of freedom, where running away was a choice to pursue this freedom.

The meaning of freedom for Black women in Charleston in the mid-19th century has long been dictated by the needs and desires of their enslavers, where oppressive systems sought to strip them of their autonomy and humanity. However, running away, aiding fugitives, and sharing stories about runaway slaves are three acts of defiance led by enslaved women to reclaim agency over their own lives and redefine the meaning of freedom on their own terms.

Running away from bondage is a direct rejection of the status quo and a courageous assertion of one's right to self-determination and dignity. As shown in the advertisements in the Charleston Courier, countless Black women refused to accept the narrow definition of freedom dictated by their oppressors and decided to instead forge their own path towards freedom. Moreover, supporting and sharing stories about runaway women served as a form of collective empowerment and solidarity within the enslaved community. These narratives not only inspired hope and courage among those contemplating escape, but also challenged the dominant narratives of slavery. Through choosing to aid slaves, running away themselves, and sharing runaway stories, enslaved women affirmed their humanity and resilience. These are three powerful acts of self-determination and resistance through which Black women in Charleston asserted their right to define freedom on their own terms. These actions by Black women serve as a poignant reminder that true freedom cannot be bestowed by oppressors but must be fought for and reclaimed by those who have been unjustly deprived of it.

Works Cited for Secondary Sources

Block, Sharon, and Stephanie M. Camp. “Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South.” The Journal of Southern History 71, no. 4 (November 1, 2005): 893. https://doi.org/10.2307/27648929.

Sorensen, Leni Ashmore. “‘So That I Get Her Again’: African American Slave Women Runaways in Selected Richmond, Virginia Newspapers, 1830-1860, and the Richmond, Virginia Police Guard Daybook, 1834-1843 .” Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. College of William & Mary, 1996. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-dy63-ex80.

Marshall, Amani T. “‘THEY ARE SUPPOSED TO BE LURKING ABOUT THE CITY’: ENSLAVED WOMEN RUNAWAYS IN ANTEBELLUM CHARLESTON.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 115, no. 3 (2014): 188–212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24393311.