Victoria P

Victoria Page '25

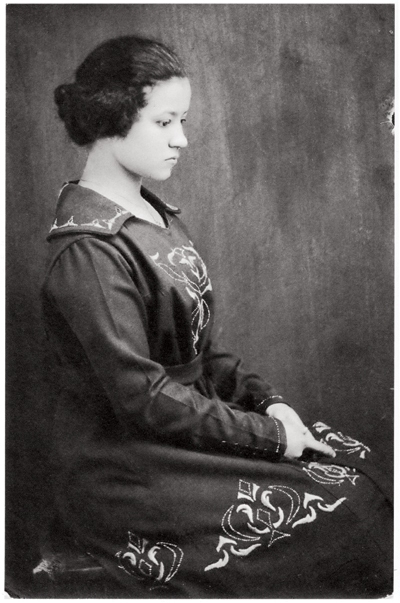

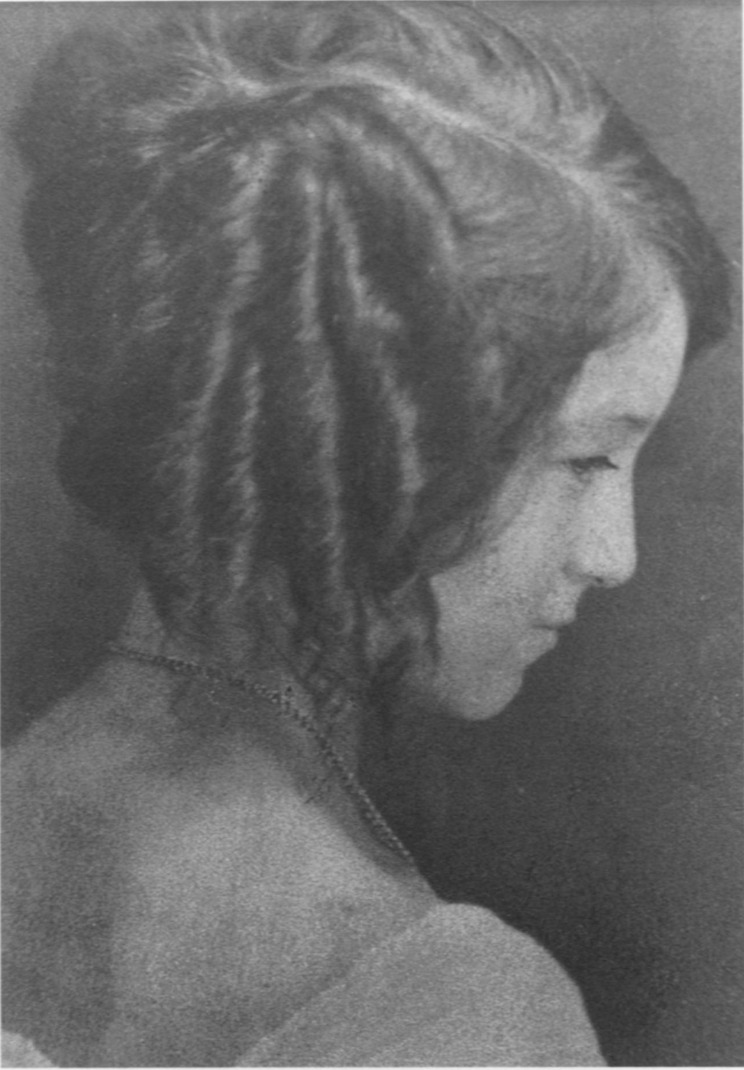

Florestine Perrault (Bertrand) Collins was not a traditional woman of her time. Born in New Orleans in 1895 to Theophile Perrault and Emily Jules Perrault, Florestine was the eldest of her siblings. She was shaped by the downtown New Orleans black Creole community where Florestine benefited from the familial and social networks in early 19th century New Orleans. She attended private school before having to drop out and begin working to help support her family at the young age of fourteen. Florestine worked for six years under white photographers before she opened her studio in 1920 out of the comfort of her own home. Florestine found success with photography by capturing black Americans in a positive light unlike the negative stereotypical pictures of propaganda that African Americans were typically pictured in. Florestine’s career lasted up until 1949 when she closed the business and retired to Los Angeles with her second husband, Herbert W. Collins. She lived until 1988. Florestine Perrault Collins was a progressive and nonconformist woman during her life. She used her work as a way to change the narrative of black people in the United States while challenging patriarchial stereotypes throughout her lifetime. Following the summation of her career, she used her work as tool for advocacy and activism throughout the civil rights movement.

In the early 20th century, photography was a welcoming career for women in the United States. Many were portraitists and photojournalists who had the eye to capture the lives of Americans in the new century. However, opportunities were still slim for black people let alone black women. When Florestine reached 14, she was tasked with assisting in providing for her family. Florestine found success getting a job when she passed as being white. “White skin functioned as a cloak in antebellum America. Accompanied by appropriate dress, measured cadences of speech, and proper comportment… passing would allow racially ambiguous men and women to get jobs.” (Hobbs, 29) Collins' early experiences as a photographer were shaped by the social and political climate of the early 20th century. Florestine’s racial ambiguity landed her jobs and opportunities to work in the photography business including working for the Eastman Kodak Company, an opportunity that revealed her bravery. Passing was not a safe nor an easy feat and dates back to the beginning of the antebellum period as a means to escape and seek freedom. Allyson Hobbs’ A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life (2014) explores the reasoning for passing, not heavily exploring why someone would want to be white, but why someone would want to escape their innate blackness. I struggle to believe that Florestine wanted to escape her blackness because, once she was on her own feet, her photography highlighted African Americans. Her images challenged racist stereotypes and pictured black people in a respectable light. Passing was a temporary choice for Florestine that provided in the meantime for her family, but it was, also, a choice that would push her into her career.

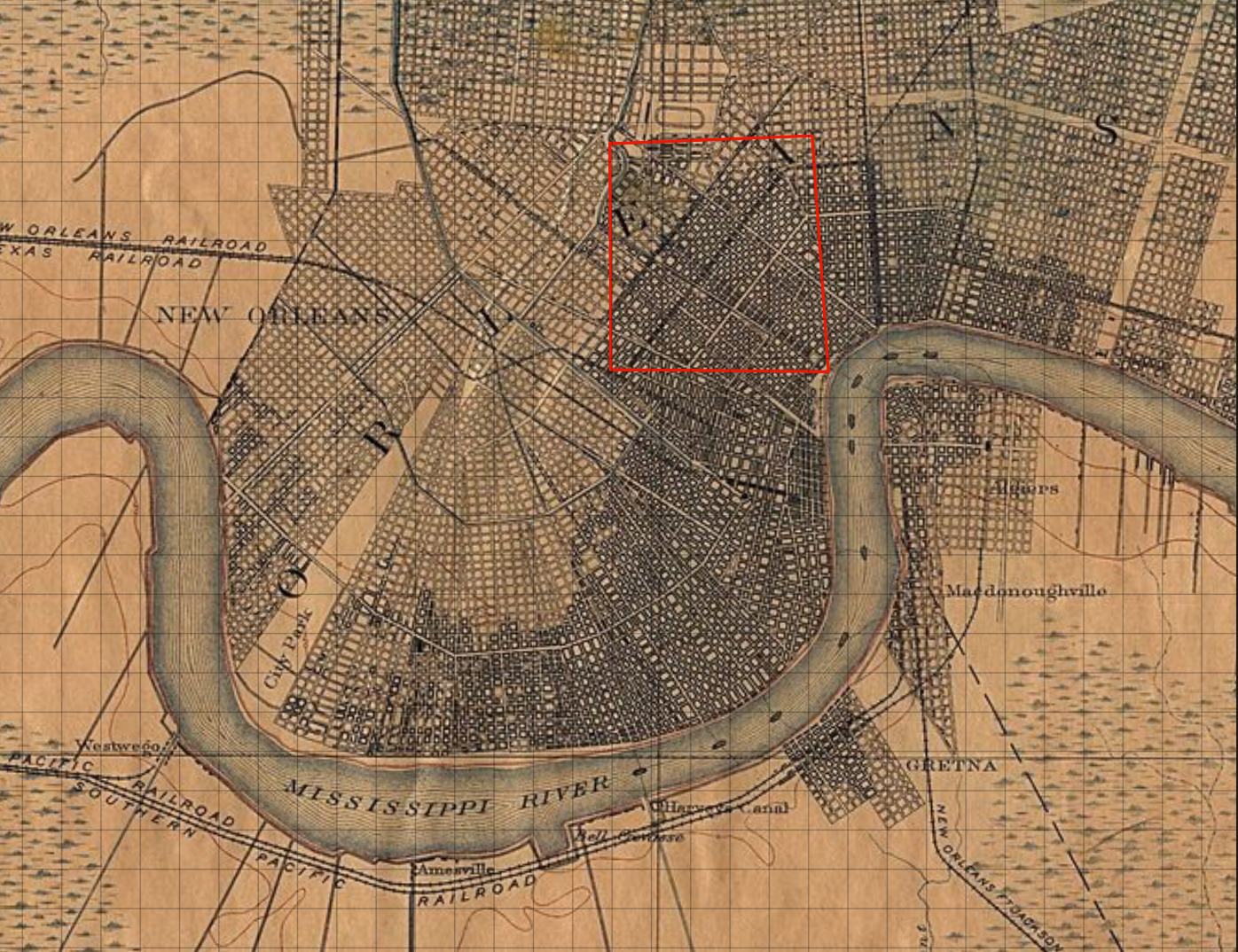

New Orleans has many things that it can be known for: art, celebration, architecture, spirituality, but the most important of them all is history. The city’s history and present rely heavily on the black inhabitants. From its beginning in the early 1700s, New Orleans quickly became the largest slave trading in the United States. French colonists relied heavily on black people to labor and provide knowledge of technology. Due to this large reliance on many black people and along with Haitian migration, the black population was able to lead revolutions from 1791 to 1811 to the end of the Civil War, New Orleans was able to become the largest population of free people of color in the South. Black people in New Orleans took advantages of the opportunities that were there. Tremé, the oldest suburb of New Orleans, became the helm for black people to reside, also, where Florestine lived and worked. Businesses thrived there for years to come and the first Black church in Louisiana was built in this area. However, there were still trials to be had for the black population. The brown paper bag test was created in response to the uprising to lower the social status of black people, regardless of them being free. With the birth of this test, passing became a new strategy to outwit white America. It’s as if Florestine lived a double life: one working for white photographers and the other by living and one providing for her family in one of the most densely populated areas that was filled with people of color. Revolutionists before her laid the way for black entrpreneurs to succeed in the city of New Orleans.

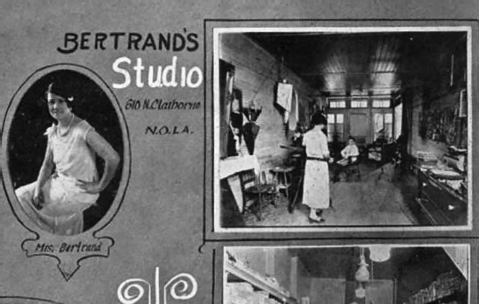

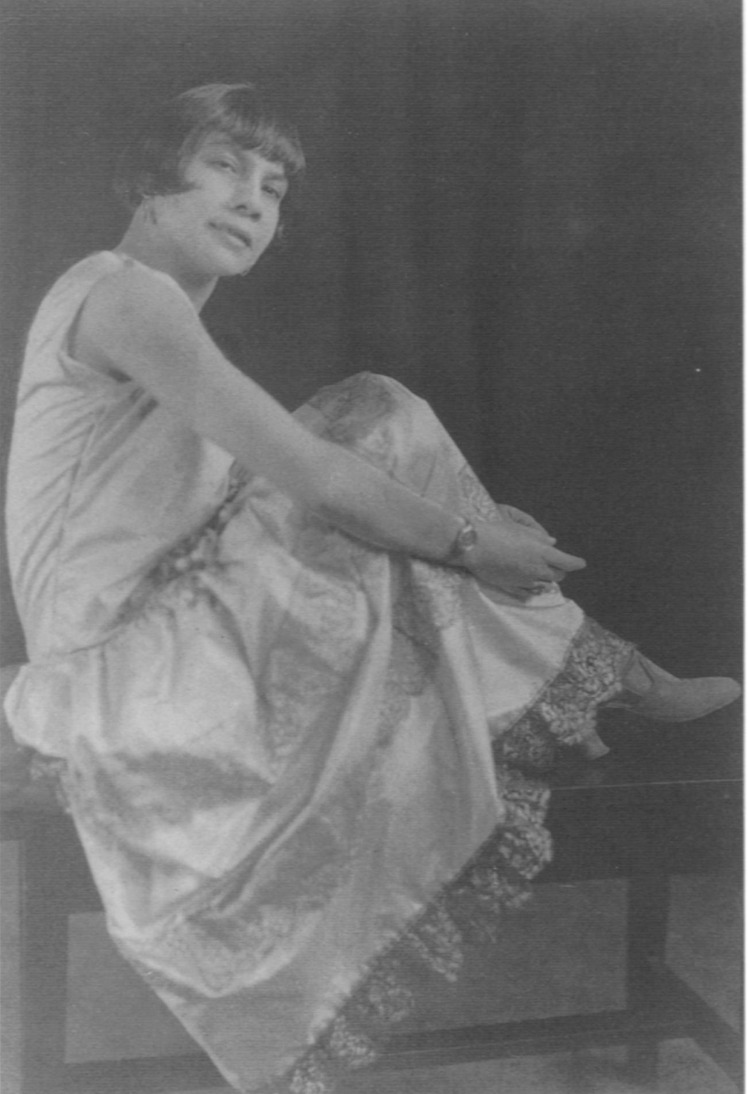

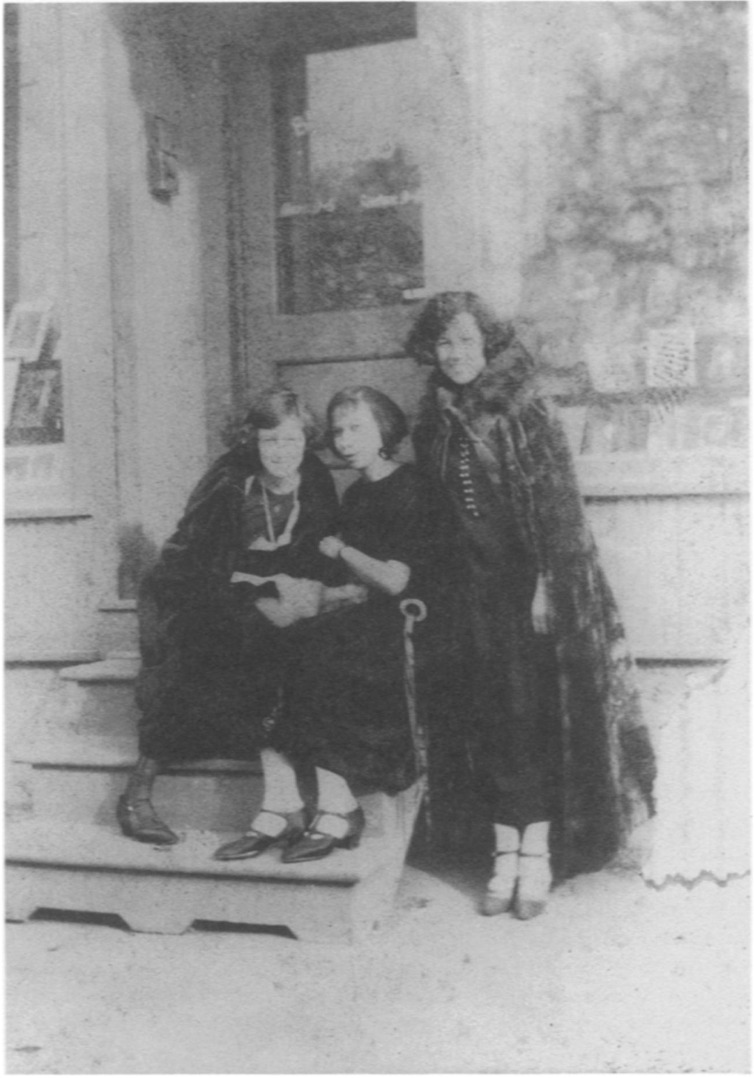

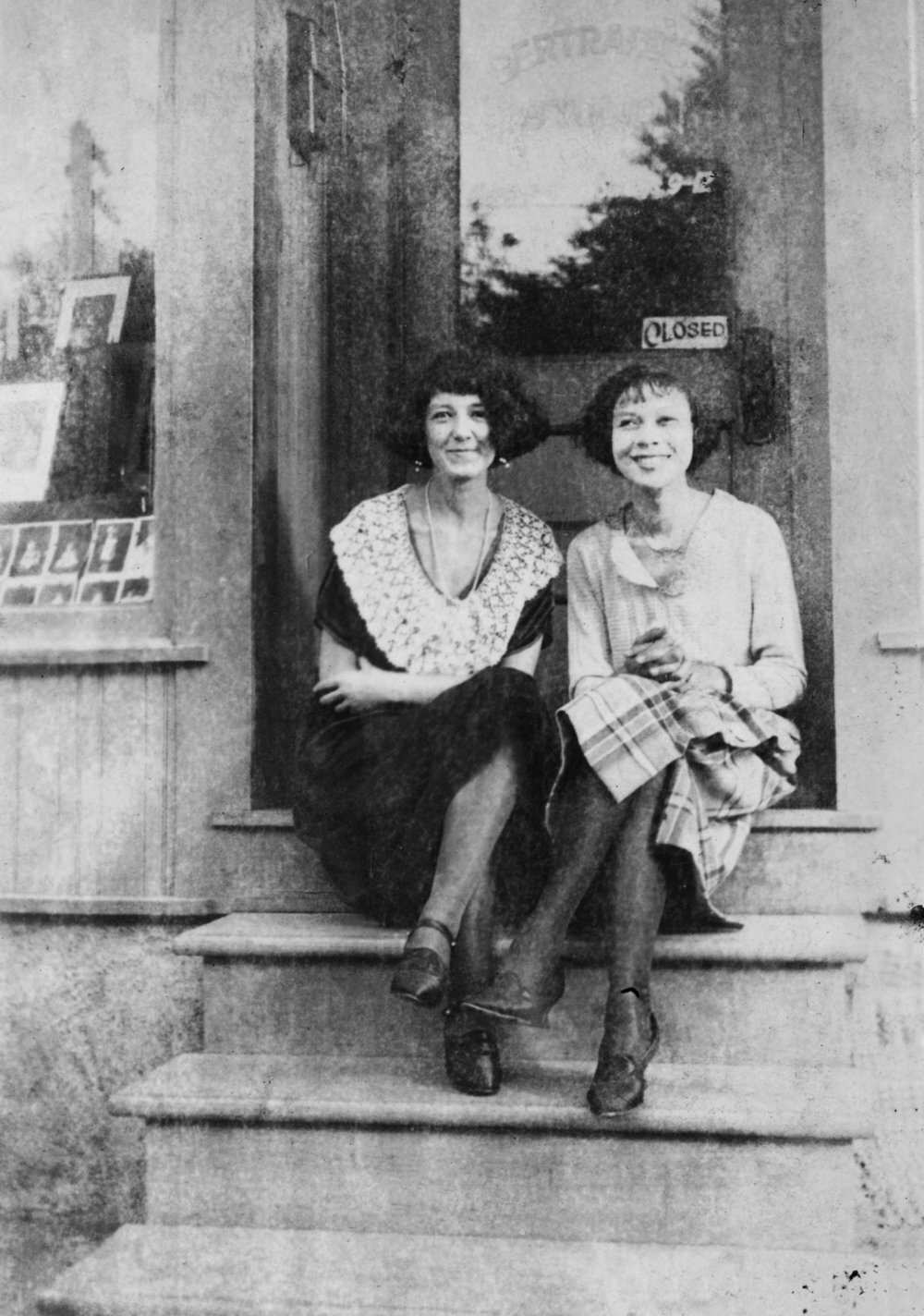

When Florestine started her own studio in 1920, she created the set in her living room: Bertrand’s Studio at 2328 St. Peter Street. At the time, she lived with her first husband, Eilert Bertrand, who was supportive of a photography career within the confines of their home. Hobbs noted that “Class and gender identities remained intact while racial boundaries were crossed. Race and gender never isolated… they are always linked.” (236) Photography was a promising vocation for women when they had studios at home because it did not bring them outside of their domestic roles. Florestine was young when she married Eilert, a rather shallow man. “She was not free to attend Mardi Gras balls that represented being “in society” to her” because he was jealous of other men. (Anthony 171) Eventually, in 1923, Florestine found a commercial space, still in Tremé, 610 North Claiborne Avenue. This move provided her with much more public exposure. Her work began to exemplify even more the everyday lives of black people, specifically, black women. Florestine photography “are representational of black women as dignified and sophisticated” (Anthony 173) Her work challenged male views on feminine roles while retaining a women’s inherent femininity.

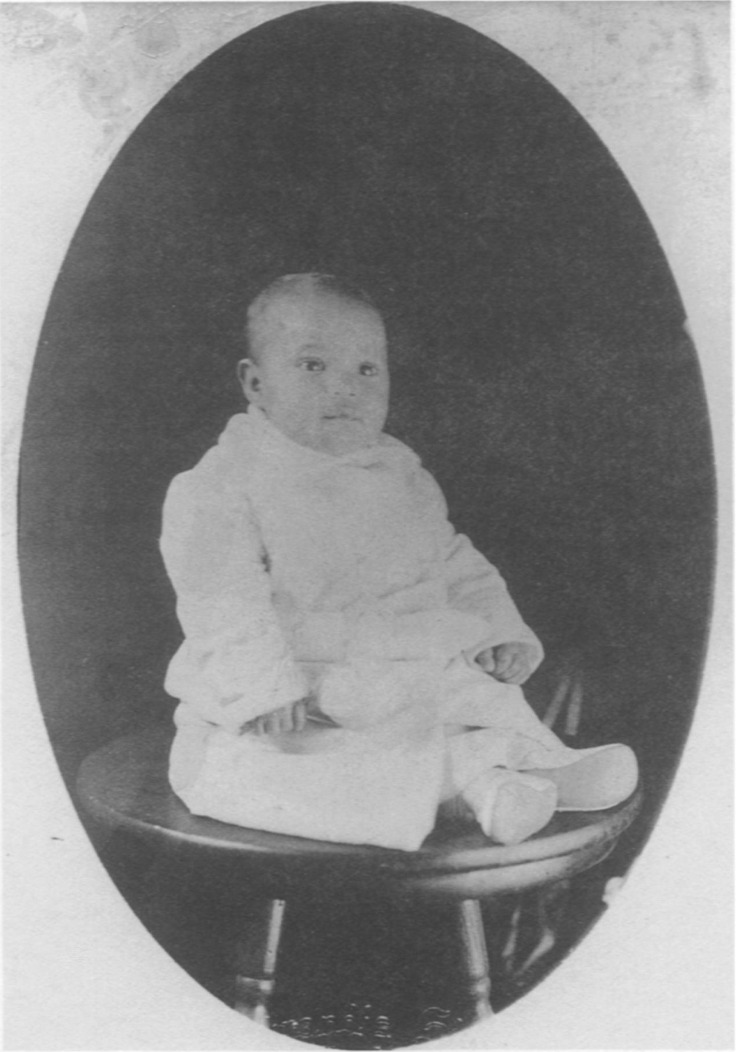

Florestine was strategic in advertising her business once she moved studios. She set her target audiences at mothers in hopes to capture the milestones in families lives while highlighting the everyday toil. Arthe Anthony, Florestine’s niece, points out how Florestine used advertising to her advantage in Florestine Perrault Collins and the Gendered Politics of Black Portraiture in 1920s New Orleans. She would add self portraits of herself to reveal her skills in portraiture while adding photos of babies and families with persuasive lines like “ Why not a picture of the child with the first book bag… preserve that wonderful moment.” (Anthony, 177) Florestine deliberately influenced her customers by offering her services to highlight milestones. Her advertising confirmed her gender and her innate propensities of motherhood. (Lopez) This was an interesting strategy considering that Florestine never had any kids in any of her marriages. However, her marketing proved that her being a woman gave her maternal instincts and ability to reach mothers regardless of her birthing any children.

Collins' photography was a form of resistance in a society that sought to marginalize and dehumanize people of color in New Orleans. In a time of rampant discrimination and segregation, Collins captured the everyday experiences of her community with sensitivity and respect. Her photographs depicted the joy, resilience, and beauty of African American life, countering the negative stereotypes perpetuated by mainstream media. Deborah Willis, an artist and photographer, appreciated Florestine's work. She recognized Florestine as 1 of only 101 black photographers in "the 1920s era of the "New Negro"." (Anthony, 168)Through her lens, Collins highlighted the humanity and dignity of her subjects, showcasing their strength and humanity in the face of adversity. Overall, Florestine Perrault Collins' photography was a form of resistance that challenged stereotypes, advocated for social change, and empowered her community. Through her art, Collins displayed the beauty and strength of African American life, and used her camera as a weapon against oppression.

Works Cited:

Arthé A. Anthony. “Florestine Perrault Collins and the Gendered Politics of Black Portraiture in 1920s New Orleans.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 43, no. 2 (2002): 167–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4233837.

Barney, Tammy C. “Florestine Perrault Collins Photographed Black New Orleans.” Verite News, March 8, 2024. https://veritenews.org/2024/03/08/florestine-perrault-collins-photography/.

Cinelli, Gwen. “Florestine Perrault Collins.” OURS, August 2, 2017. https://www.oursphotomag.com/blog/florestine-perrault-collins-1920.

Fikes, Robert. “The Passing of Passing: A Peculiarly American Racial Tradition Approaches Irrelevance •.” THE PASSING OF PASSING: A PECULIARLY AMERICAN RACIAL TRADITION APPROACHES IRRELEVANCE, September 12, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/passing-passing-peculiarly-american-racial-tradition-approaches-irrelevance/.

Florida, University Press of. “New Film Shares Pioneering Photography of Florestine Perrault Collins.” The Florida Bookshelf, September 3, 2017. https://floridapress.blog/2014/12/12/new-film-shares-pioneering-photography-of-florestine-perrault-collins/.

Hobbs, Allyson. A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life. Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2014. https://doi-org.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674735811

Lopez-Diago, Zoraida, and Lesly Deschler Canossi. Black Matrilineage, Photography, and Representation: Another Way of Knowing. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022., https://doi.org/10.1353/book.102917.

“Some New Orleans Black History You Should Know.” Banner, May 29, 2023. https://utno.la.aft.org/new-orleans-black-history/some-new-orleans-black-history-you-should-know.