Nathan T

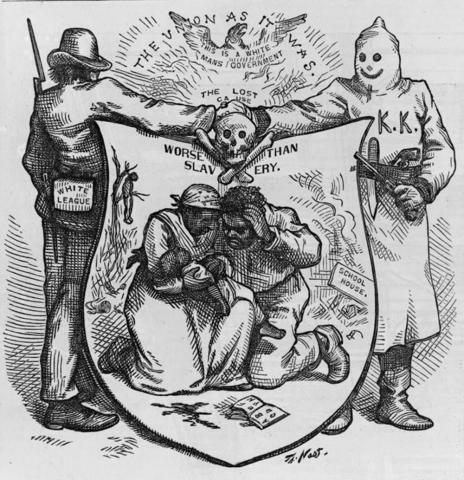

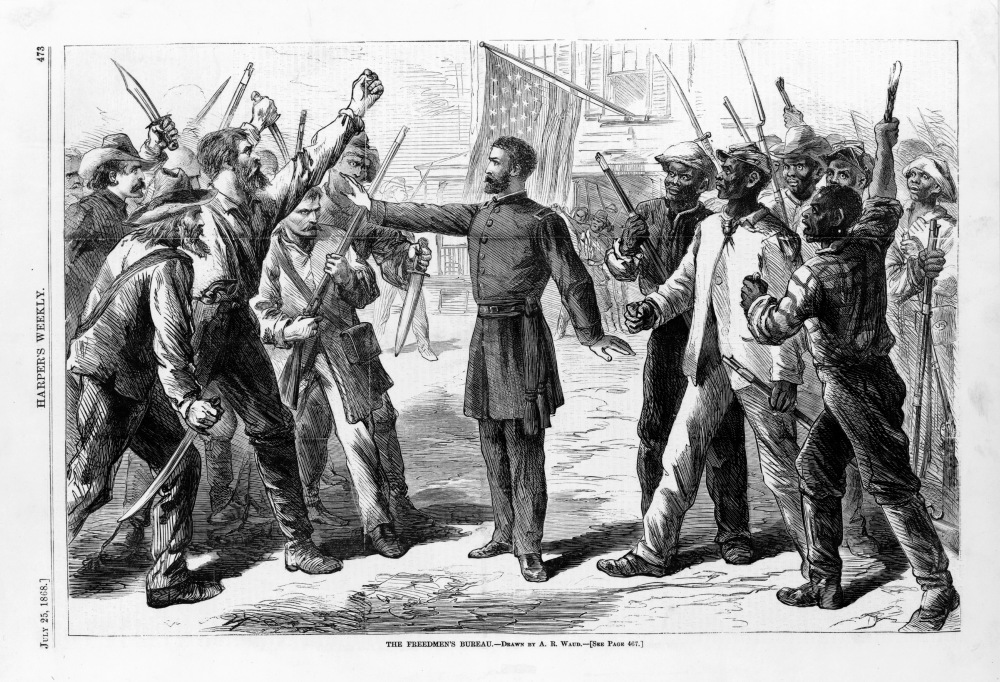

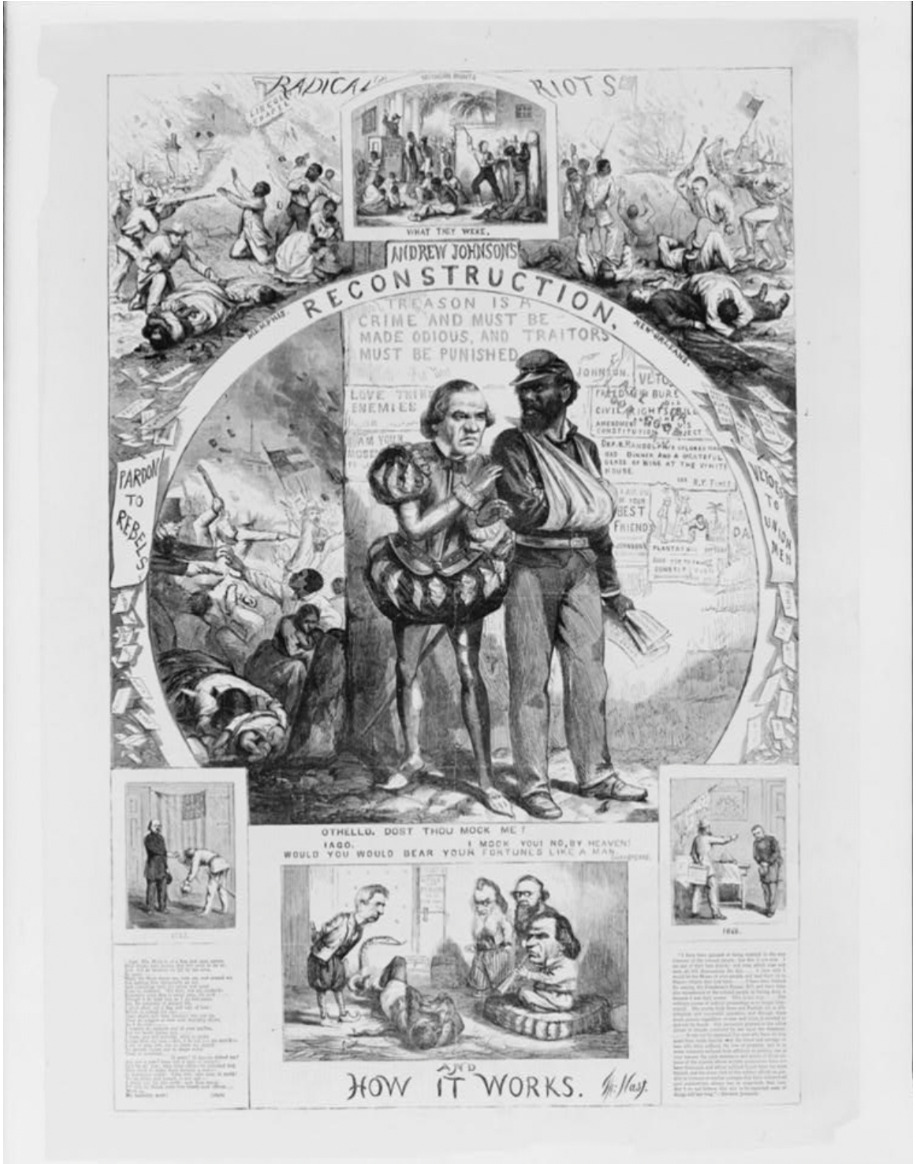

The Emancipation Proclamation, and the resulting abolishment of slavery drastically shifted the landscape of the Southern United States both socially, economically, and interpersonally. The transition from the slavery in the Old South to the emancipated New South was plagued by complex interactions of historical forces, including industrialization, reconstruction, the impacts of the lingering of structural racism, ultimately resulting in inequality. Black women during this period saw the creation of new opportunities and challenges as they navigated their roles as free individuals within a society still grappling with the legacies of slavery. While the Civil War brought about the formal abolition of slavery, resulting in a momentous change in the status of Black women, many of the same issues concerning freedom and equal treatment were pervasive. Free from actual chains, Black women were now confronted with the daunting task of creating new and personal identities, as well as struggling to assert themselves in a society that was still unequal. Their rights as newly free women in a society were deeply entrenched in racial hierarchies because of the remnants of slavery, and defining to themselves what it meant to be free in this system was incredibly difficult. These struggles often came to a head in the realm of black labor, because the freeing of slaves shifted the societal norm for how woman of all races participated in the labor market. As articulated in the essay, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor, "because slavery was first and foremost a system of forced labor, its end naturally involved a renegotiation of the role the formerly enslaved people would play in the labor force." (Berlin, 1) Freed people sought the right to work when and where they chose for fair wages, while former slaveholders tried to retain as much control over their labor as possible. White workers, fearing competition and perceiving a threat to their own economic stability, resisted the idea of free African Americans entering the labor market, as shown by the cartoons below.

“One reads the truer deeper facts of Reconstruction with a great despair. It is at once so simple and human, and yet so futile. There is no villain, no idiot, no saint. There are just men; men who crave ease and power, men who know want and hunger, men who have crawled. They all dream and strive with ecstasy of fear and strain of effort, balked of hope and hate. Yet the rich world is wide enough for all, wants all, needs all. So slight a gesture, a word, might set the strife in order, not with full content, but with growing dawn of fulfillment. Instead roars the crash of hell...”

W.E.B. Du Bois

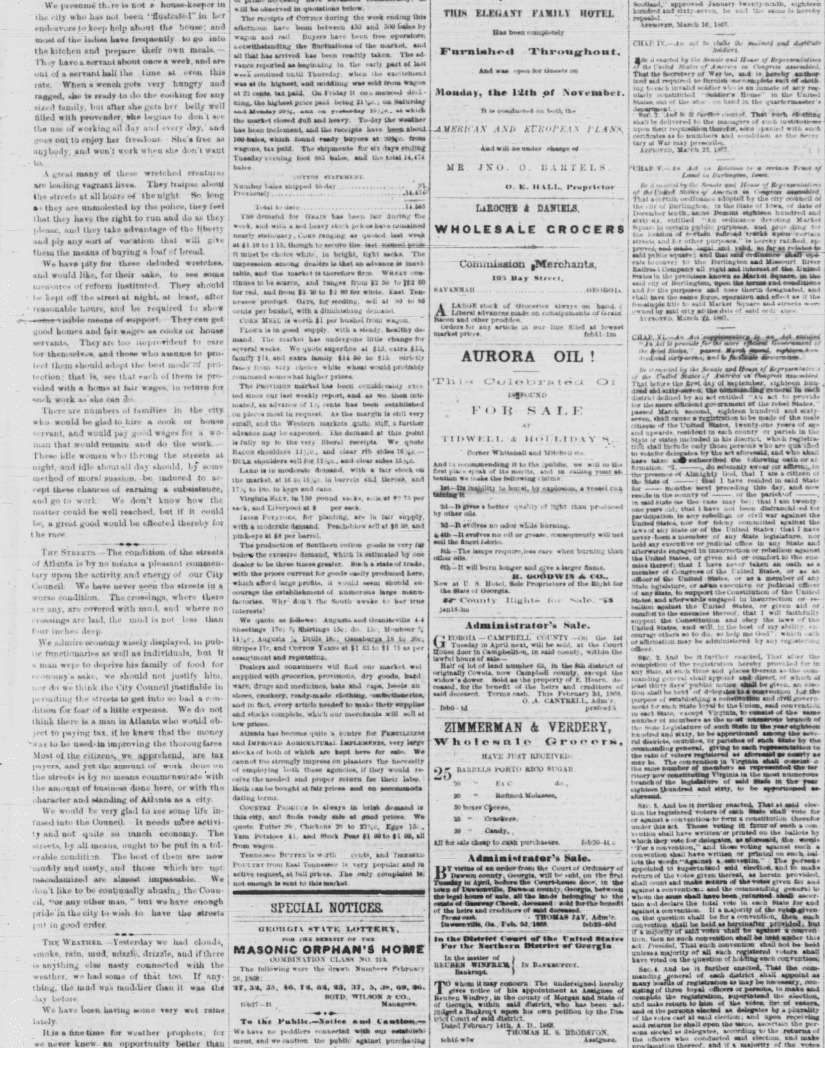

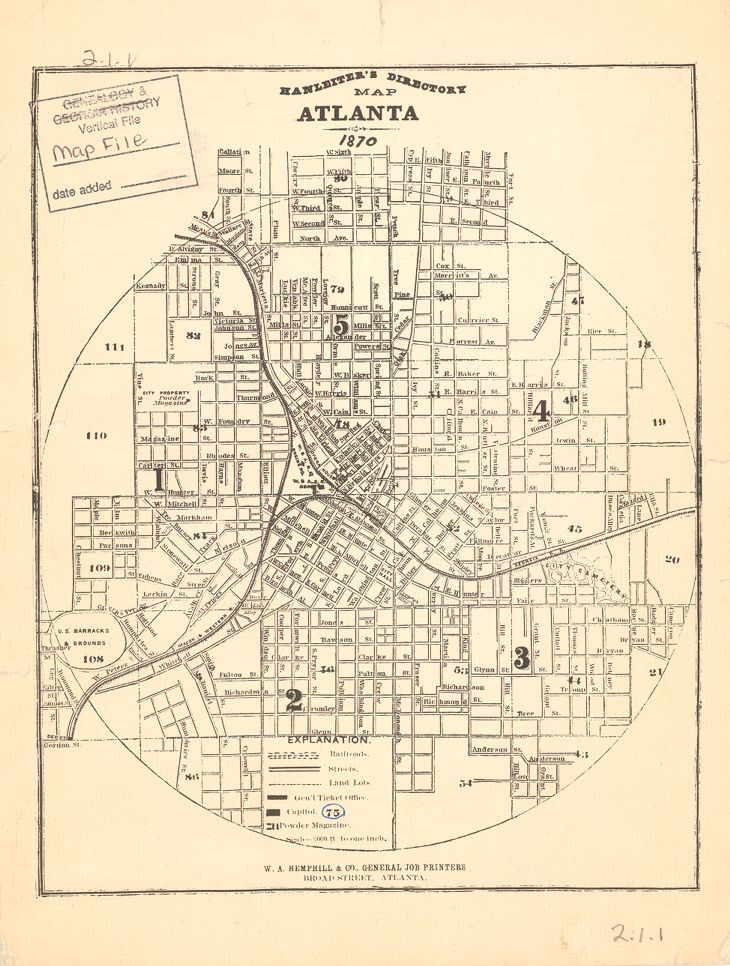

As noted further in the above essay, "White workers did not like competing economically with free African Americans any more than they had with enslaved people." (Berlin, 1) This sentiment was fueled by concerns that employers would replace them with new "unfree" workers or that the federal government was favoring African Americans over poor whites. There were published accounts from the time period portraying freed slaves as idlers, perpetuating stereotypes to undermine their economic agency. Despite such opposition, black women persevered, seeking economic independence and asserting their rights within a society deeply entrenched in racial hierarchies. As they navigated the tumultuous currents of Reconstruction and structural racism, their articulations of justice and freedom were not merely abstract ideals but lived realities shaped by the complexities of post-slavery America. Dr. Tera Hunter further elucidates the challenges faced by African-American women, in the book To ‘Joy My Freedom, noting that they were largely confined to domestic work. They engaged in constant struggles to define themselves outside of labor, while white employers constantly sought to impose an identity that defined African-American women solely as laborers. Dr. Hunter, through the life story of a Black woman, Rosa Lee Ingram, outlines how the promise of equality from the Emancipation Proclamation had created hope, despite the remnants of inequality that still persisted. Black women were at the forefront of the efforts to dismantle these vestiges of racism, and sought to gain political power and influence through their further integration into society, and their labor. However, this change did result in considerable push back. After the end of slavery, “Nearly all began life in freedom without tools or land. How would they feed, clothe, and house themselves?” (Berlin, Page 1) During the period of enslavement, “the slaves' labor had enriched their owners”, and none of the benefits of labor went to those who were enslaved. (Berlin, Page 2) With recently free individuals struggling to find a means of supporting themselves and families, Black women found themselves at the intersection of white Americans and their racism and fear of Black women and their labor encroaching on their livelihood. These fears are articulated in the cartoons below, and the newspaper article that articulates a “domestic drama”, and are used to highlight the situation and feelings of society during the Reconstruction period. (Atlanta Daily New Era, 1868) Black women during this time frame were constructing business of their own and for the first time harnessing their labor as a means of producing wealth for themselves and their families, despite all of the forces that sought to hinder this process. This transition and integration into society enabled a new vector with which Black women could push for increased equality and societal change, and this was initially employed during the Reconstruction era in the deep south in Atlanta, Georgia, where the Washerwoman’s protests served as an impetus for class based action that bonder together the different races, and served as a template for black woman across the country as a means of effecting change.

"Woman must not depend upon the protection of man, but must be taught to protect herself."

Susan B. Anthony

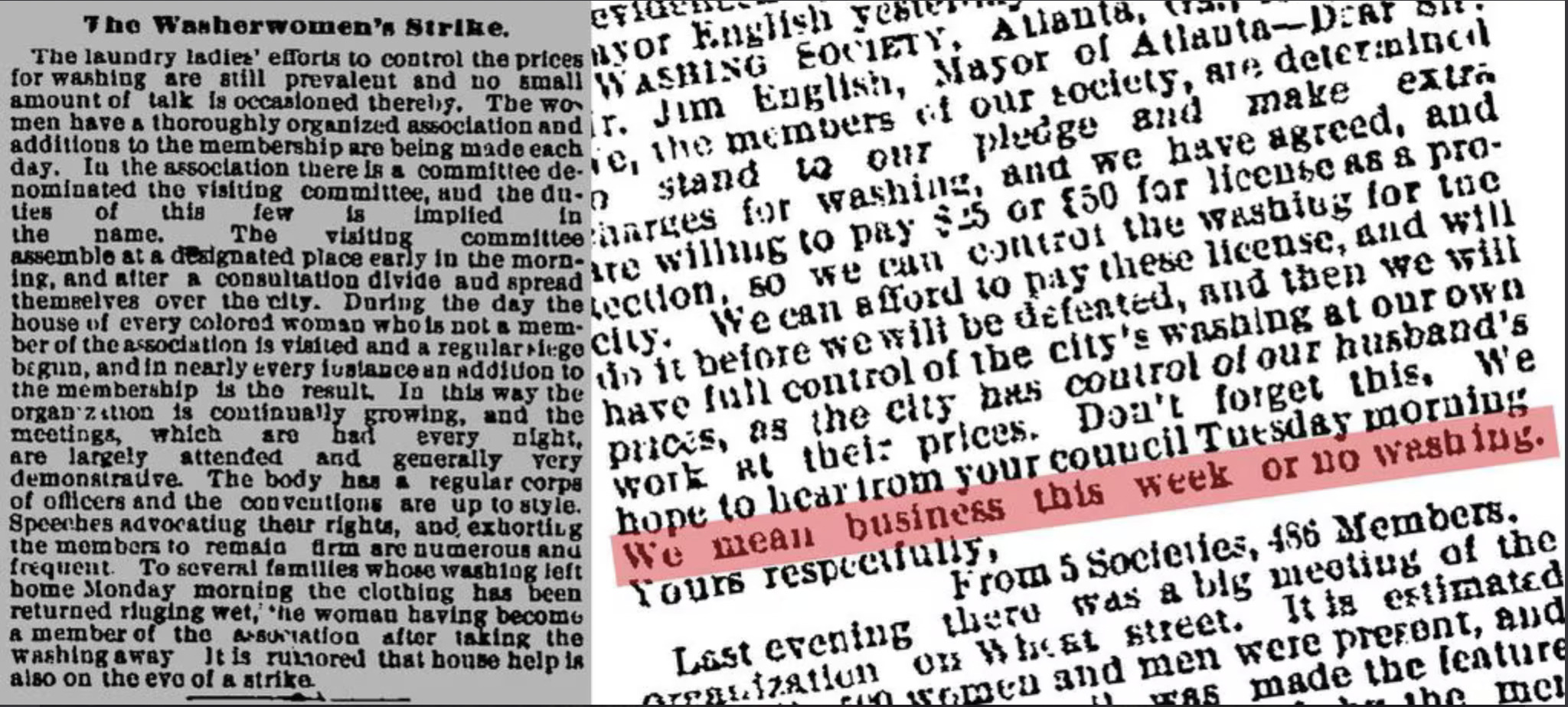

Atlanta, Georgia was home to an exemplary template for how black women played significant roles in various spheres of society during the Reconstruction Era, including activism for civil rights and labor rights. One notable example is the Washerwomen's Strike of 1881, where in the late 19th century, Atlanta's economy that was primarily driven by the textile industry and other manufacturing sectors was booming. However, this growth came at the expense of exploited labor, particularly among African American women who worked as washerwomen. These women faced harsh working conditions, low wages, and discrimination. Some of these conditions include, but are not limited to scrubbing for many hours, hauling water and heavy irons, and making their own supplies, all while being payed a measly sum of $6 a month. (Hunter, 8) The attached newspaper clipping from the Atlanta Constitution articulates this situation and what the workers were dealing with. An initial group of 6 black washerwomen organized a strike to demand better wages and working conditions, and they communicated among themselves through word of mouth, community gatherings, and possibly through churches or other social networks, organizing meetings to plan their protest strategy and coordinate their actions. According to Dr. Hunter in To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War, these women were then promptly arrested and fined as a result of the Atlanta Washerwomen Strike. After these arrests, the protest grew bigger, with 20 women now joining the cause as they all felt the same frustration that arose from poor wages and treatment and debilitating working conditions. The workers demanded higher wages, and the protesting snowballed to eventually total 3,000 individuals, capturing the attention of the entire city, and serving as the impetus for broader civil disobedience for low wage workers. (Hunter, 12)

“There is no possible conflict between the good of society and the good of its members, of which the industrial workers are the vast majority.”

–Margaret Haley

The primary tactic that these protestors employed was the withdrawal of labor, refusing to do laundry until their demands were addressed, as well as prayer circles, nightly meetings, and picketing to increase awareness and pressure business owners into acquiescing to the demands of a uniform pay rate of $1/ dozen pounds of laundry. Dr. Hunter articulates the reactions to these protests, by quoting a newspaper article that describes how “The Washerwomen’s strike is assuming vast proportions and despite the apparent independence of the white people, is causing quite an inconvenience among our citizens” while at the same time describing the demands of the Black washerwoman as extreme. (Hunter, 16) Paradoxically, while at the same time saying that Black women were asking for too much compensation, white women of all classes were refusing to do laundry themselves at home, because they did not want to subject themselves to this incredibly difficult chore. There was a considerable back and forth between these opposing groups, as despite the lack of launders, clothing was still being worn, and needed cleaning. Customers, mainly white woman, were becoming increasingly frustrated with the fact that clothing was not being washed and therefore gained a rancid stench. The collective bargaining and peaceful refusal to work served as a means to resist the oppressor, and like it was during slavery, ultimately was a successful technique. Dr. Hunter notes this success by describing how quickly white laundry customers succumbed to the pressure and folded, with there being women only one week into the strike who sought to give into the workers’ demands. While wealthier women were able to send their laundry two neighboring regions and cities, those white women of a lower socio-economic background were not so fortunate. So, lower economically privileged white women, which were more likely to be impacted by this process were then subsequently more likely to support Black women with their labor movements in the washing industry. (Hunter, 24) By aligning on a common interest, these two groups of people were able to narrow a schism that had been formed through years of slavery and oppression. The common interest of Black woman getting back to work in the laundries created solidarity amongst Black women and white women, and through this solidarity, incentives were created that pushed businesses and local governing bodies to comply. The added voices of poor white women compounded with black women, and through the absence of black washerwomen, was able to turn into legislative changed. Ultimately these protests resulted in success, were the demands of Black women being fairly compensated for their labor were met, and the city council dropped their threats and possible punitive actions.

More then just an effective template for protest, the Black washerwomen walkout in Atlanta Georgia was also indicative of how black women viewed their own labor, and the role of protest. The demands in this protest reflected Black women and their understanding of fair workplace conditions and their rights as free women, seeking higher wages commensurate with the value of their labor, better treatment from employers, and an end to discriminatory practices. Underlying these desires for rights is a deeper understanding of what it means to be a Black woman, how black women should interact amongst one another, and the ultimately the meaning of freedom. By studying this protest, Dr. Hunter noticed that much of the communication between black women stemmed from prayer and their involvement in house duties, such as taking care of children, etc. Black women were largely responsible for these tasks, as well as working outside the home in fields that were similar to what they did inside the home. As a result of this, much of their political power stemmed from the home, and they effected change from this vantage point by using their labor, or lack of it, to alter the dynamic of the homes of white women. Prayer was apart of this notion, as religious practice was taught to children and was generally a universal part of life, so communication being centered around prayer circles plays into the dynamic of utilizing areas where Black women had power and control in order to effect change. By employing this strategy in Atlanta, Black women were able to have some incredibly impactful and lasting outcomes to the protest. The first major source of accomplishment was the actual physical changes on the ground that were enacted for Black washerwomen as their labor was duly recognized. Another important change was the recognition that grassroots mobilization and protest could peacefully and effectively lead to change, as seen by the resulting media and consumer attention, increased wages, and solidarity that Black women gained throughout this process.

Beyond just the material improvement for the lives of Black women in Atlanta, this protest also had broad implications for the rest of the south, and US history in general. This protest served as the template for a plethora of other protests that erupted through the south in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas to name a few. Deep analysis of this impetus event is important because it allows for the contextualization of all similar movements that happened throughout American history and recognition of these brave women who started it all. These actions in Atlanta show how dedicated Black women were to freedom and equality and through the creation of this resistance template, allowed their labor to catalyze the push for equality throughout American History.

Secondary Sources:

Hunter, Tera W. To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War. Harvard University Press, 1998.

Berlin, Ira "The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Case of the Contraband Women." Journal of American History, vol. 87, no. 4, 2001, pp. 1271–92.