Franklin Expedition and Domino Effect

In 1845, Sir John Franklin led the Discovery Expedition, consisting of the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, with the goal of discovering and crossing the Northwest Passage. Franklin captained the HMS Erebus, with Francis Crozier leading the HMS Terror, a total crew of 129 people, and over 8,000 tins of food - enough to sustain them for three years [1]. But the entire expedition disappeared and remained lost for decades. The mystery of the lost Franklin expedition captured the attention and imagination of Europeans, expanding the public's facination with the Arctic and leading to a tremendous increase in Arctic exploration.

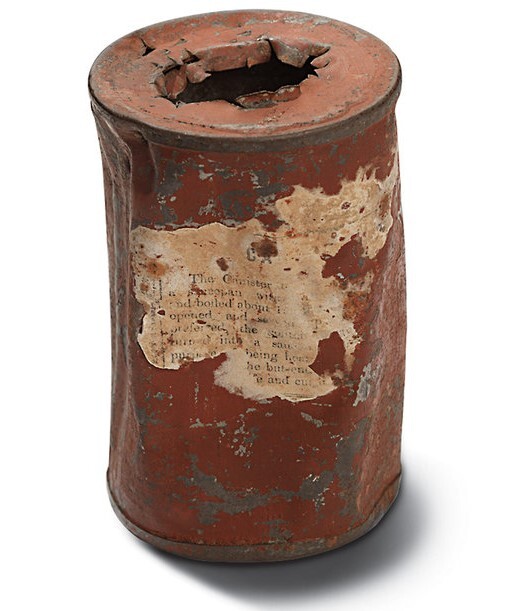

The ship would become icebound in the Canadian Arctic in 1846 - the crew, including Franklin, presumably perished, never to be heard from or seen again. The expedition faced a multitude of problems throughout their journey, starting before they even set off. At the time, the typcial rations supplied to sea expeditions included salted pork and dry goods, but Franklin's expedition drew up a contract with Stephen Goldner, who canned food using cutting edge technology for the time. His contract was drawn up only 7 weeks before the expedition's departure, however, so Goldner had to rush to complete the massive amount required to feed the crew. Trying to meet his deadline, Goldner increased can sizes and decreased the time the cans were cooked from 7-11 hours to only 30-75 minutes. Little did he know, this left much of the food at the center of the can uncooked, resulting in food poisoning for much of the crew [3]. After the remains of the expedition were finally found, the extent of the horror the crew members faced became clear. Many of the bodies showed signs of scurvy from vitamin C deficiencies, and some skeletons showed markings suggesting they had been canabalized. Many of the remains also contained high amounts of lead, which is thought to have come from either the hastily soldered cans of food or the ship's water filtration system [4].

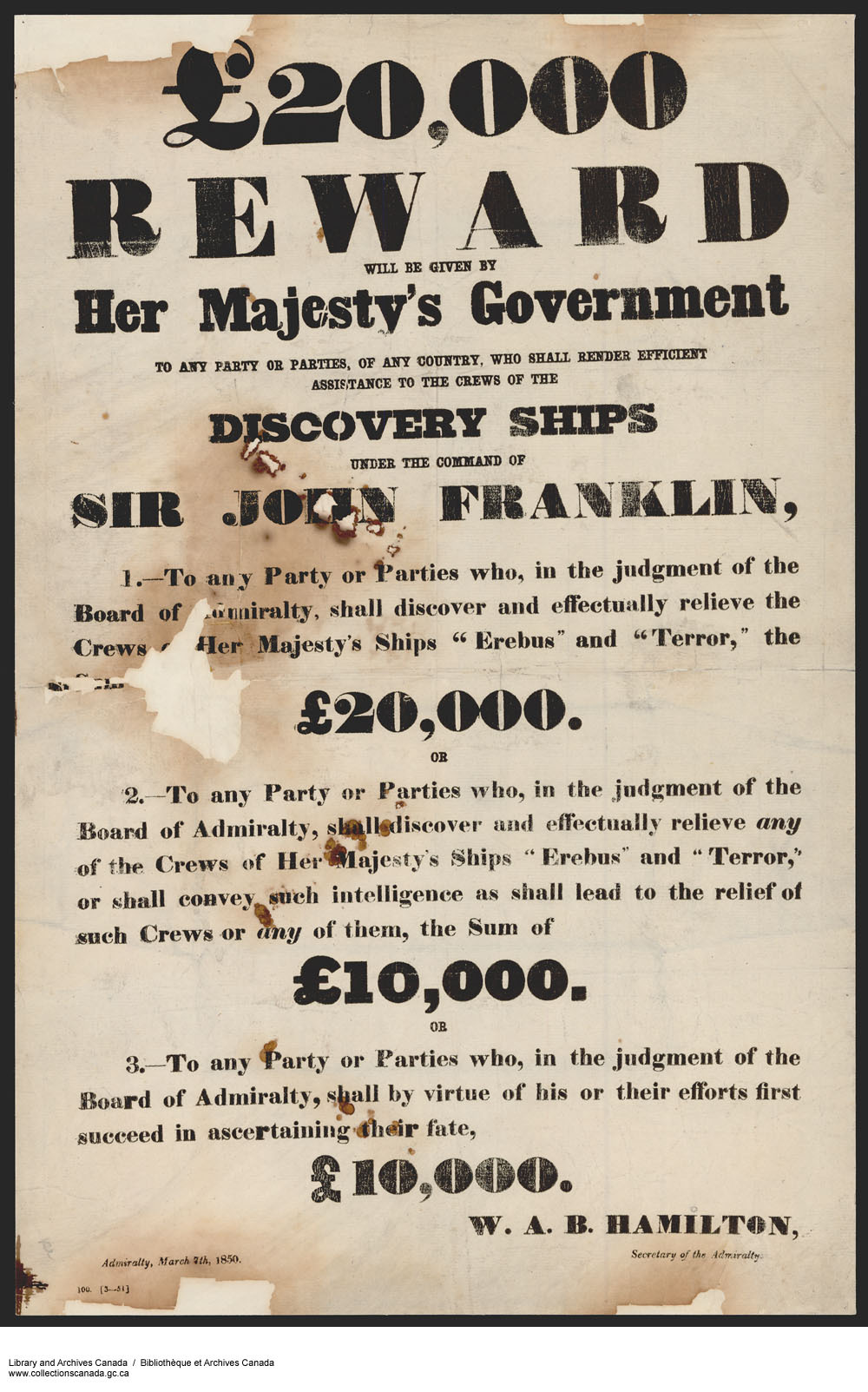

Because the trip was anticipated to take years even in the best of conditions, the first overland search for the lost Franklin Expedition did not begin until the spring of 1848. News spread quickly, however, and this missing expedition captured the attention of explorers and civilians alike, across Britain and beyond. The English government offered rewards for those who found either ship or learned what happened to the crew, encouraging an influx of Arctic exploration in the following years, as well as cementing the Franklin Expedition in the minds of the public for centuries to come.

"Ah, for just one time I would take the Northwest Passage To find the hand of Franklin reaching for the Beaufort Sea"

Northwest Passage - Stan Rogers

The search to find the lost Franklin Expedition led to an explosion of European exploration into the Arctic. And these explorations, though many were laregly unsuccessful in finding information about the Franklin expedition, brought back various other valuable information about the Arctic regions. For instance, Robert McClure led an expedition in 1850, setting out to find Franklin and his crew. Instead, the expedition ended up being the first to cross the North-West Passage over ice [2]. Inhuit peoples had first-hand knowledge of the fate of Franklin and his crew, and in 1854 John Rae brought back stories and artifacts the Netsilik Inuit had given him about the greusome end of the expedition. But when Rae returned to England and spread the tale of cannibalism and hardship, Lady Jane Franklin, the explorer's widow, launched a smear campain. Aided by the abundant racism in English society, the narritve quickly switched back to one of heroism and mystery [5].

The two ships of the Franklin expedition, the Erebus and the Terror, were not found until many decades later, in 2014 and 2016 respectively. Both ships were found submerged near Nunavut's King William Island. At long last, these two pieces of the puzzle of the fate of the Franklin Expedition have been found. Though much of the story has been lost to time, thanks to the perseverance of countless explorers, scientists, and Inhuit groups, the mystery of the disappearance of the Franklin Expedition, which once captivated so much of the European public, can be put to rest at last.

Sources

[1] Mercer, K., & Neatby, L. (n.d.). Sir John Franklin | The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 19, 2023, from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-john-franklin

[2] Robert McClure North-West Passage expedition 1850-54. Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved May 22, 2023, from https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/robert-mcclure-north-west-passage-expedition-1850-54

[3] Ricketts, B. (2014). The Franklin Expedition: What Really Happened? Mysteries of Canada. Retrieved May 22, 2023, from https://mysteriesofcanada.com/nunavut/franklin-expedition/

[4] Witzenburg, F. (2020). The Lost Franklin Expedition. US Naval Institute. Retrieved May 22, 2023, fromhttps://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2020/october/lost-franklin-expedition

[5] Eschner, K. (2018). Tales of the Doomed Franklin Expedition Long Ignored the Inuit Side, But “The Terror” Flips the Script. The Smithsonian. Retrieved May 22, 2023, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/heres-how-amc-producers-worked-inuit-fictionalized-franklin-expedition-show-180968643/