The Copper Inuit: An In-Depth Analysis

Introduction

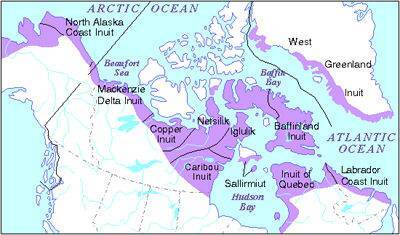

The Copper Inuit, who are descendants of the Thule people, are a group of indigenous Inuit who live in the westernmost regions of traditional Inuit territory in Arctic Canada and modern-day Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, which are home to some of the harshest climates known to man. Their English name is derived from the fact that they gathered copper from the nearby Coppermine River to make copper tools and weapons. This group of indigenous people are interesting to analyze for several reasons. The Copper Inuit have a rich cultural heritage and social structure that allowed them to maintain their cultural identity in the face of external pressures. Further, this group of indigenous people were one of the last indigenous groups to have contact with outsiders and maintained their traditional lifestyle longer than many other Inuit communities. Studying their encounters with explorers and the subsequent changes they experienced can shed light on the dynamics of cultural contact and the impacts of colonialism. Their narrative of civilization is shaped by their unique history, environment, and cultural practices. This analysis delves into the intricacies of the Copper Inuit narrative, exploring their social organization, division of labor, trade systems, and adaptability to changing circumstances.

Nomadic Lifestyle and Dwelling

Like many historical Inuit groups, the Copper Inuit did not have permanent houses. According to Stefansson's expedition accounts, they relied on temporary shelters and tents, likely due to their nomadic lifestyle. Their transient nature of dwelling reflects their deep connection with and education of the land they resided on and their ability to adapt to changing environments during different seasons and years. This nomadic lifestyle also underscores their self-sufficiency and mobility in hunting and gathering activities, which is abundantly important when considering food and resource security while living off of the land.

Egalitarian Social Structure

The Copper Inuit's sociocultural system is characterized as highly egalitarian, which included no formal positions of leadership and instead relied on elder knowledge. Integral to Copper Inuit society was a family, kin, and band oriented social organization. Their societal structure placed high importance on consensus decision making and functioned like a modern day democracy. The Copper Inuit’s egalitarian ethos fostered cooperation, communal decision-making, and a sense of equality within their bands that spanned a few hundred miles. This demonstrates their deep appreciation for collective well-being and the significance of harmonious relationships within the community and with the land.

Gender-Based Division of Labor

The Copper Inuit practiced a gender-based division of labor, although there were instances where individuals could engage in tasks typically associated with the opposite gender. As is standard across many different indigenous groups, men primarily engaged in hunting to supply food for their families and communities, while women assumed more “homemaking” responsibilities such as mending clothes, cooking, and childcare. The absence of strict taboos regarding gender-based work allowed for flexibility and adaptation based on individual circumstances, promoting the overall resilience of the community. This idea is heavily talked about in Stefansson's Expedition.

"There is a general rough division of labor between the sexes although under certain circumstances a man may do any kind of woman's work and a woman any kind of man's work. There is no taboo restriction in this matter apparently. At any rate it seems to me that men among the Copper Eskimo and in fact all Eskimo whom I know, are less likely to mind doing such work as mending clothes, cooking, or looking after children than white men would be under similar circumstances. But besides this sexual division of labor there is a rudimentary one of another sort. Lame men or others for some reason not well able to hunt are likely to be occupied in the making and mending of implements and utensils and in some cases a man's skill at bow-making or pot-making is well known to be superior to the average and he therefore makes bows and pots for his neighbors occasionally merely as a favor, but sometimes also for pay. Commonly a man who makes pots, for instance, is thereby handicapped in hunting and is consequently paid in caribou skins which he needs to clothe himself and his family."

Vilhjalmur Stefansson, 1914

Trade Systems

Intragroup and intergroup trade systems were essential to Copper Inuit society. Cooperation and alliances were formed through trade, contributing to the social and economic interconnectedness of different bands. The specialization of certain individuals in crafting specific items, such as bows or pots, created interdependencies within the community. Trade was often facilitated through reciprocity and mutual aid, reflecting the ethos of communal support and cooperation.

Adaptation

The Copper Inuit demonstrated remarkable adaptability in response to changing circumstances, such as the decline of caribou herds. Their ability to adjust hunting strategies and engage in alternative activities, like making and mending implements and utensils, exemplified their resourcefulness. This adaptive mindset was crucial for their survival in the challenging Arctic environment, highlighting their profound connection with the land and their willingness to embrace change.

The adaptation is also a factor of how this group changed after contact with outsiders and explorers. For example, Rasmussen recorded that a major diminution of caribou herd numbers had occurred. This was mostly due to overhunting of this mammal by Inuit who were now using rifles they had acquired from outside visitors. This example shows a difference in the Copper Inuit’s culture post European/Canadian contact.

Population

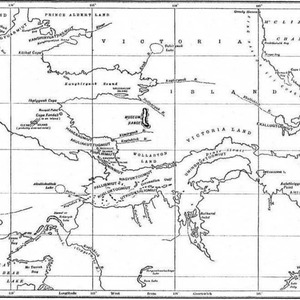

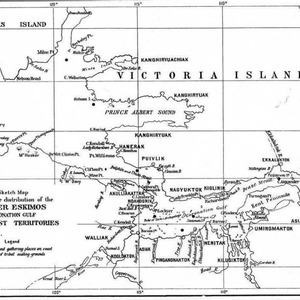

Stefansson (1919) estimates the Copper Inuit population at 1,100 individuals in nineteen bands, while Rasmussen (1932) estimated the population at 816 individuals spread throughout fourteen groups. Below are maps from each of their respective explorations that detail their personal experience with regional distribution of different Copper Inuit groups.

Conclusion

The Copper Inuit narrative of civilization showcases their remarkable resilience, adaptability, and egalitarian values. Their nomadic lifestyle, consensus-based decision-making, and gender-based division of labor reflect their deep understanding of their environment, ability to thrive in challenging conditions, and deep appreciate for one another. The emphasis on trade, cooperation, and resource management underscored their interconnectedness and the importance of communal support. The Copper Inuit narrative serves as a testament to their enduring cultural heritage and provides valuable insights into the dynamics of Inuit civilization, highlighting the significance of sustainability, cooperation, and adaptability in their way of life.

Sources

[1] Johnson, D. S. (2010). Close World-System Encounters on the Western/Central Canadian Arctic Periphery: Long-Term Historic Copper Inuit-European and Eurocanadian Intersocietal Interaction (thesis). University of Manitoba.

[2] https://collections.dartmouth.edu/arctica-beta/html/EA08-07.html

[3] Stefansson, V. (1914). The Stefansson-Anderson Expedition of the American Museum: Preliminary Ethnological Report. American Museum of Natural History, Volume 14 Part 1.