Inuit Folk-Tales

[Polar Bear Folk Tales]

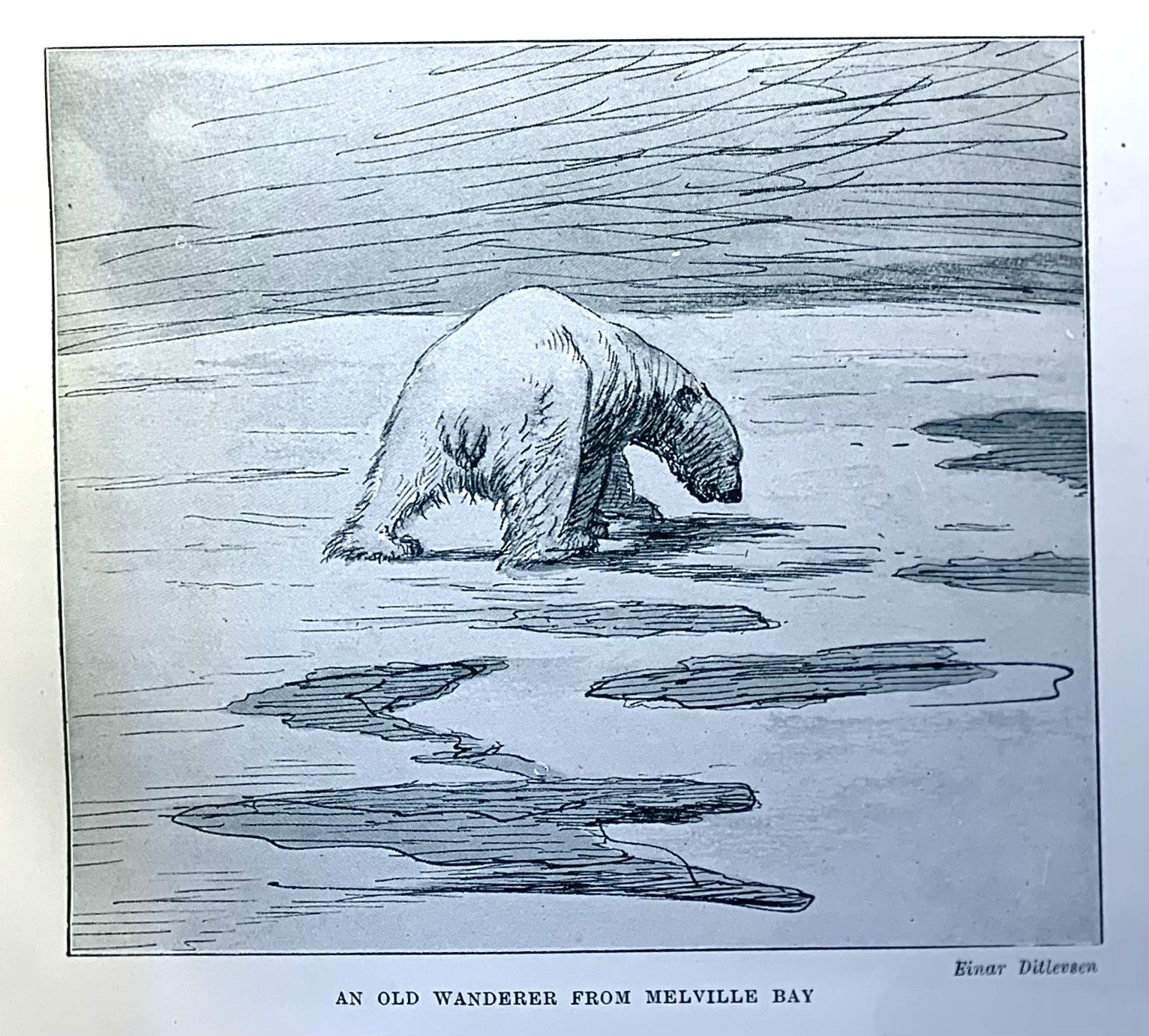

There are many stories and folk tales involving polar bears. The Inuit believed that all creatures have souls, with the polar bear spirit, Nanuk, being considered as one of the most powerful, dangerous, and vengeful one.

1) Kunik + Bear-Mother:

This Inuit legend tells the story of a woman who adopted a polar bear cub, naming him "Kunik". The woman and Kunik formed a strong bond quickly, with the village children loving him as well, treating him as a sibling. As the days and years went by, Kunik became smarter and stronger, learning to fish and bringing back seal and salmon for his mother. However, before long, the village men became envious and plotted a scheme to kill Kunik. A child overheard this plot and warned the woman, who with tears in her eyes, begged the bear to run away so that he would be away from danger. After a few days of separation, the woman became determined to track down her child, and thus went out to find him. She lost hope after a couple hours, but soon saw Kunik running towards her, and embraced him. Kunik, seeing that his mother was hungry ran to hunt some fresh meat and fish, which they shared. The mother vowed to return the next day to meet him, so she did, day after day, with the villagers growing to understand the strong bond between the woman and bear. And from that day on, they tell this story of unbroken love with pride and respect.

2) Angutdligamaq + Anoritoq:

A man named Angutdligamaq never hunted but would kill successful hunters and steal their seals. Others lived in fear of him but finally agreed that something must be done. They decided to teach him how to hunt, but Angutdligamaq proved exceedingly clumsy and had to be shown how to do everything, including how to sleep in a snow house. The others told him he'd sleep best if he left one leg out of his trousers.

When his companions saw Angutdligamaq's bare backside exposed, they buried a spear in it. Angutdligamaq jumped up, bellowing with pain and rage, but this agitation only forced the spear farther in, and the murderer died. His mother, Anoritoq, mourned for her son and asked the hunters to give her a bear embryo, that she might raise it as her child.

When the hunters took a pregnant bear, they presented the unborn cub to Anoritoq, and she raised it as her son, so it could catch seals for her. All went well until winter. Unable to see seals in the winter darkness, the bear began stealing other families' meat. Soon the bear's cousisn, the village dogs, surrounded him and held him unitl the people killed him.

Anoritoq sobbed a song to her dead bear-son until the tears froze on her cheecks and her body turned to stone.

[Island Dwellers and Man-Eaters Folk Tales]

In the book Eskimo-Folk-Tales by Rasmussen and Worster, the stories are organized by theme with sections featuring bears, island dwellers, and man-eaters. The stories range from hunting, violence to wizardry, magic and shapeshifting.

Rasmussen notes that the folk tales he records include “parallels to the fairy tales and legends of other lands and other ages,” as well as providing historical evidence, though they are otherwise works of fantasy.

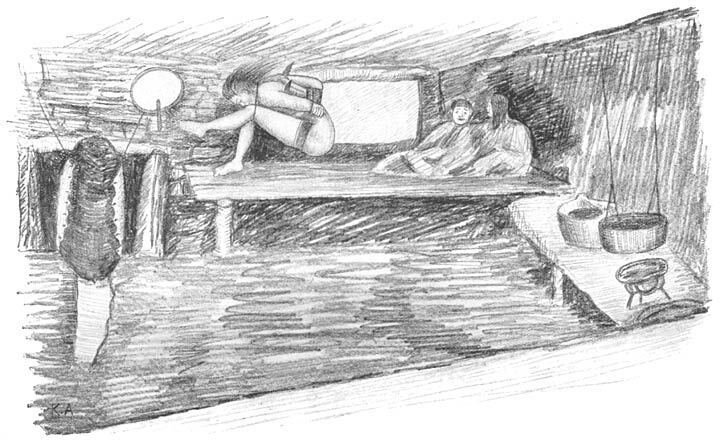

The tales weave in supernatural elements to the typical 20th century Inuit day to day life of hunting walruses, driving dog sleds and preparing meals. These Inuit tales are rich with tales that reflect their relationship with the natural world and their beliefs in spirits and supernatural beings. These stories often explore themes such as survival, the power of nature, moral lessons, and the importance of community.

“Not one of you eating, and here a newly-killed whale?”

When he said this, Qujâvârssuk answered:

“None may eat of it until my mother has first eaten.”

But the strong man tried then to take a mouthful, although this had been said. And when he did so, froth came out of his mouth at once. And he spat out that mouthful, because it was destroying his mouth.

And they brought that catch home, and Qujâvârssuk’s mother ate of it, and then at last all ate of it likewise, and then none had any badness in the mouth from eating of it. But the strong man sat for a long time the only one of them all who did not eat, and that because he must wait till his mouth was well again.

And the strong man of Amerdloq did not catch a whale at all until after Qujâvârssuk had caught another one.

For a whole year Qujâvârssuk stayed at Amerdloq, and when it was spring, he went back southward to his home. He came to his own land, and there at a later time he died.

And that is all.

~To face p. 34.

The tales told in this book often end with an unceremonious death of the protagonist.

“He came to his own land, and there at a later time he died. And that is all”. ~ p.37

“Here I end this story: I know no more” ~p.19

“Here ends this story” ~ p.74, 141, 147

“And I have no more to tell of him” ~p.80

“And that is all I know about the Giant Dog” ~p.96

“This story I heard from the men who came to us from the far side of the great sea” ~p.106

These endings are practical to close the short tales told by Rasmussen and Worster. The upruptness of these endins encapsulate an unspoken world.

Supernatural elements reflect deep spiritual beliefs and close connection to the natural world. Here are some common supernatural elements found in Inuit folk tales:

-

Shamans and Spirit Communication: Inuit culture places great significance on shamans, who are believed to possess spiritual powers and the ability to communicate with the spirit world. Shamans play a crucial role in many folk tales, acting as intermediaries between humans and spirits.

-

Shape-Shifting: Shape-shifting is a prevalent theme in Inuit folklore, where beings such as animals, spirits, or humans can transform into different forms. These transformations often serve as a means of disguise, survival, or supernatural intervention.

-

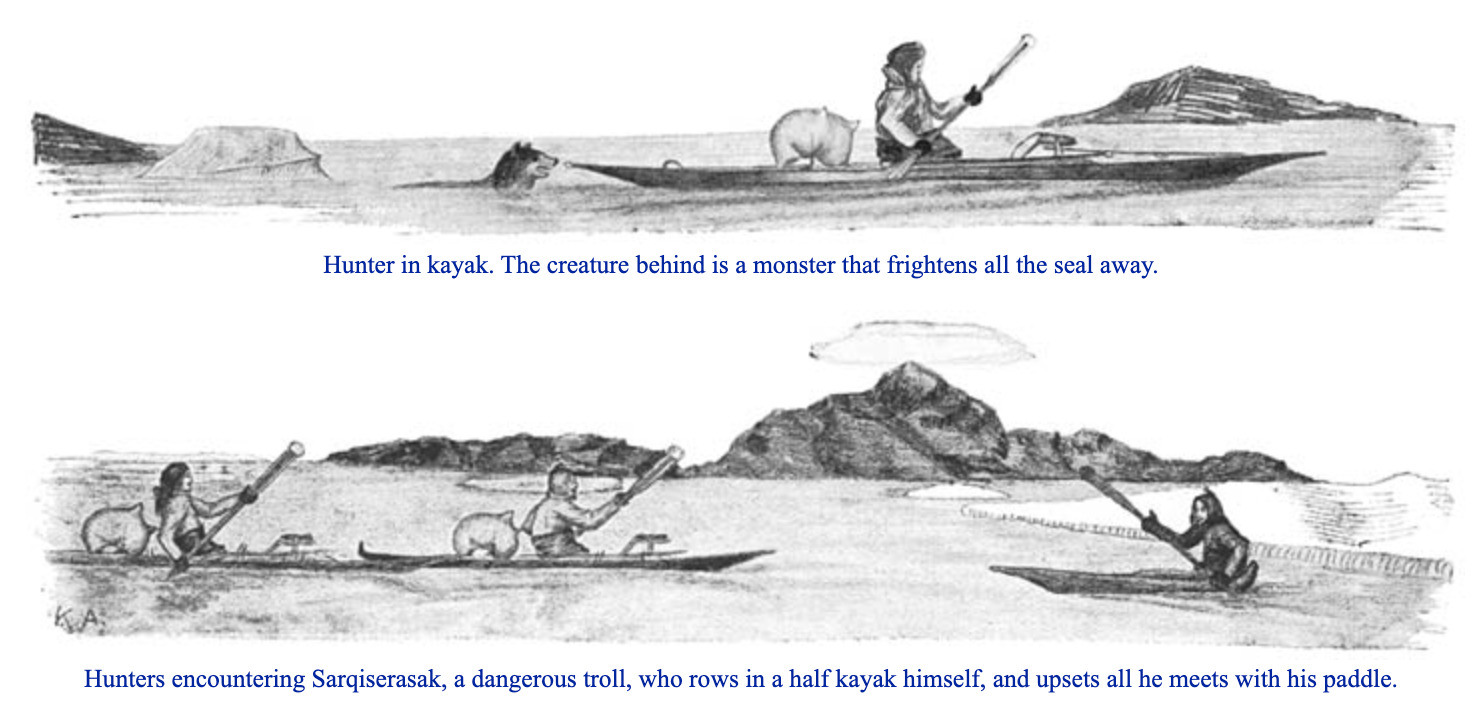

Mythical Creatures: Inuit mythology includes various mythical creatures and spirits, such as the Qalupalik (a sea-dwelling creature that kidnaps children who wander too close to the water), the Sedna (a sea goddess associated with marine life and the underworld), and the Tuurngait (malevolent spirits or demons).

-

Ancestor Spirits: Inuit folklore frequently emphasizes the importance of ancestors and their continued presence in the lives of the living. Ancestors are believed to watch over and protect their descendants, often appearing as spirits or guiding forces in folk tales.

-

Magical Objects and Powers: Some Inuit folk tales feature magical objects or powers that grant special abilities to the characters. These objects can range from enchanted tools and weapons to talismans or amulets with transformative or protective qualities.

-

Nature Spirits and Forces: Inuit folklore celebrates the power and influence of nature. Tales often portray natural phenomena, such as the Northern Lights, thunder, and storms, as manifestations of powerful spirits or supernatural beings.

These supernatural elements in Inuit folklore serve multiple purposes, including explaining natural phenomena, teaching moral lessons, reinforcing cultural values, and providing a sense of wonder and connection to the spiritual world.

Sources:

[1] Rasmussen, Knud, and W.J. Alexander Worster. Eskimo Folk-tales. London: Gyldendal, 1921.

[2] Heiner, H. A. (2021). Eskimo Folk-Tales Introduction, Annotated Tales. SurLaLune. https://www.surlalunefairytales.com/book.php?id=56&tale=1733

[3] Burch, E. S. (1988). Knud Rasmussen and the “Original” Inland Eskimos of Southern Keewatin. Études/Inuit/Studies, 12(1/2), 81–100. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42869626