Who Reached the North Pole First?

Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6th, 1856 in Cresson, Pennsylvania. Peary entered the US Navy in 1881, and pursued a naval career until he retired. His first visit to the Arctic was in 1886, when he made an unsuccessful attempt to cross Greenland by dogsled. His next expedition in 1891-1892 was much more successful, and he was able to reach Independence Fjord (also known as Peary Land) at the northern tip of Greenland, proving conclusively that Greenland was an island. In 1894, he was the first Western explorer to reach the Cape York meteorite and its fragments, which he took from the native Inuit population who had relied on it for creating tools. He often acted with little regard toward the local Inuit people, even though he studied their survival techniques and had even fathered a child with a local Inuit woman. Peary is most famous, however, for his two attempts to reach the North Pole, one in 1904-05 and the other in 1908-09.

Frederick Albert Cook was a physician and ethnographer who embarked on numerous expeditions in the Arctic and Antarctica. He was born in Nortonville, New York, and he studied at Columbia, and then at NYU’s Grossman School of Medicine. His first position out of medical school was as a physician serving on Robert Peary’s Arctic expedition of 1891–1892, and on the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899. He contributed to saving the lives of its crew members when their ship – the Belgica – was ice-bound during the winter, as they had not prepared for such an event. He also traveled to Tierra del Fuego in South America, where he studied the local Selk’nam and Yahgan peoples. Cook twice visited Denali in Alaska, and he claimed to have been the first to summit it in 1906, but his ascent has since been proven fraudulent. After his attempt at Denali, he returned to the Arctic in 1907 in order to beat Robert Peary to the North Pole.

The two men, Peary and Cook, left from different places in the Arctic (Peary from Ellesmere island in Canada, Cook from northern Greenland) within a year of each other. Cook’s expedition departed in February 1908, while Peary departed in February 1909. Cook claimed to have reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908, after traveling north from Axel Heiberg Island, taking with him only two Inuit men, Ahpellah and Etukishook. On the journey south, he claimed to have been cut off from his intended route back to Greenland by open water, and his expedition spent over 14 months in the Arctic. His whereabouts during that time are disputed, but he reemerged on September 1st, 1909 in the Shetland Islands in Scotland claiming to have made it to the Pole. That day, he sent a telegram:

“Reached North Pole. April 21, 1908. Discovered land far north."

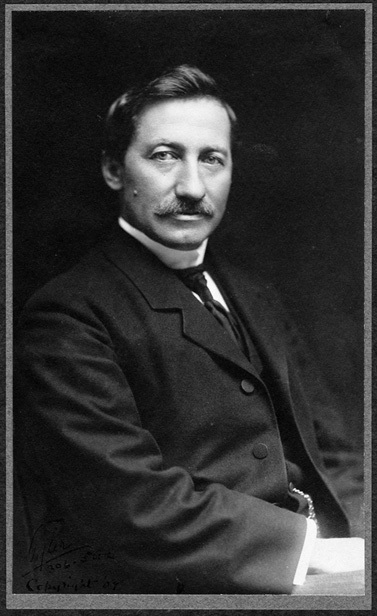

Dr. Frederick Cook, 1909

Five days later, another telegram from the Labrador Coast in Canada arrived from Robert Peary. His message:

“Stars and stripes nailed to North Pole."

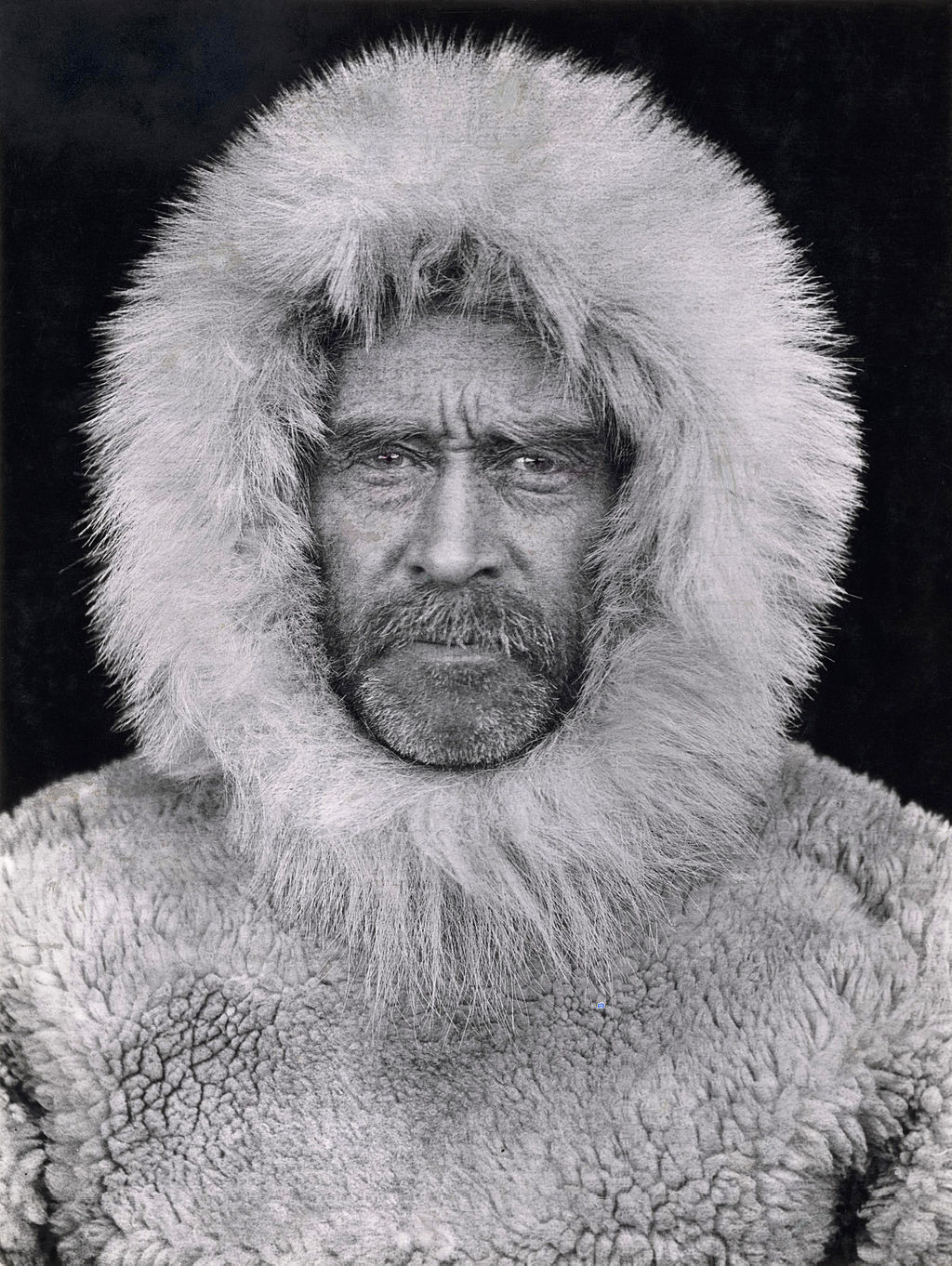

Robert Peary, 1909

Peary claimed to have arrived at the North Pole on April 6th, 1909, almost a year after Cook. Peary’s expedition had left from Cape Columbia, Ellesmere Island, Canada with a large team of supporting expeditioners and local Inuit, with a total of 7 expedition members, 19 Inuit, 140 dogs, and 28 sledges. One after the other, these supporting teams turned back for the base camp on Ellesmere Island, until only Peary, his partner Matthew Henson (an African American explorer), and four Inuit guides remained. After a march of 130 nautical miles in just 5 days, they set up Camp Jesup within 3 mi (5 km) of the pole. Matthew Henson did some forward scouting and claims to have been the first of the party to reach the pole, saying “I think I'm the first man to sit on top of the world,” much to Peary’s chagrin. The expedition returned to their ship The Roosevelt on April 26th, 1909, and on July 18th the ship departed for home, and the telegram was sent from the first station they came across in Labrador, Canada.

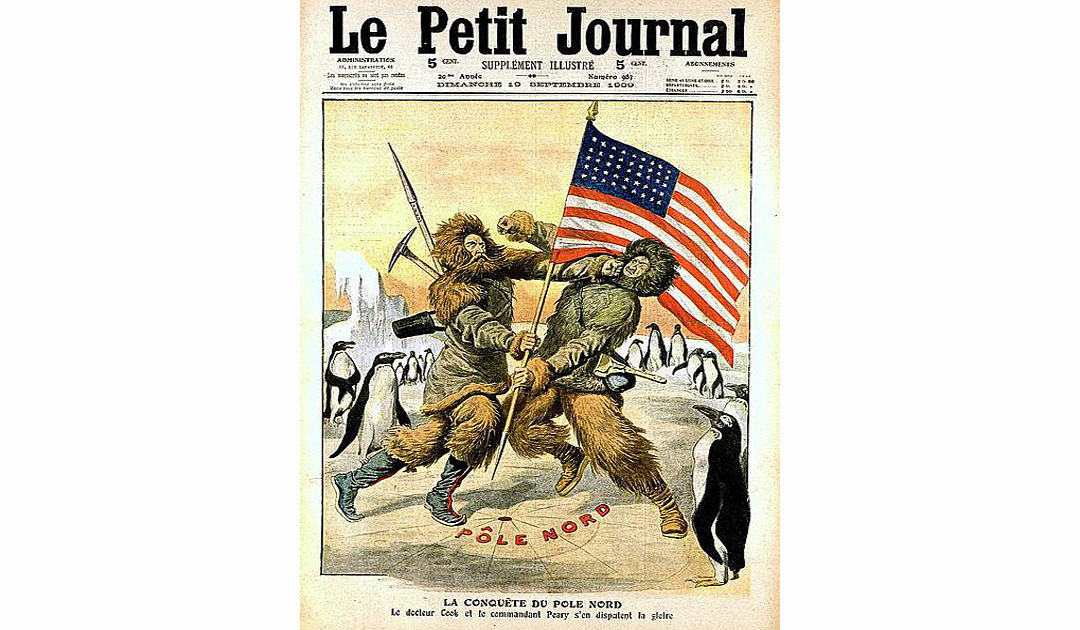

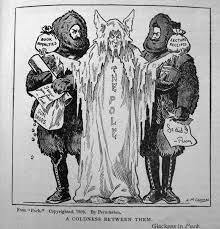

The Great Race to the North Pole between Peary and Cook remains hotly contested, and the veracity of both men’s reports have been challenged over the years. When both men returned from their expeditions in 1909 the international press made a large deal over their rivalry, and that rivalry only grew in later years. Peary and his supporters launched a campaign to discredit Cook, which was buoyed by the fact that Cook never produced original navigational records to substantiate his claim to have reached the North Pole. He said that his detailed records were part of his belongings, contained in three boxes, which he left at Annoatok, Northern Greenland, in April 1909. On December 21, 1909, a commission at the University of Copenhagen, after having examined evidence submitted by Cook, ruled that his records did not contain proof that the explorer reached the Pole. Peary largely escaped having his records evaluated by other explorers. He was eventually recognized by the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. Congress for "reaching" the pole by a vote of 4-3 and given the Thanks of Congress by a special act in March 1911. Many experts have cast doubt on Peary’s claim, however, since he did not submit his evidence for review to neutral national or international parties or to other explorers. His claim was certified by the National Geographic Society (who funded his expedition) after a brief examination of his records, but later criticisms included omissions in navigational documentation, inconsistent travel speeds, and apparent additions to his diary around the days of his arrival at the North Pole. As for Cook, criticisms against his evidence included incorrect sextant navigational data and conflicting accounts from his Inuit guides about where the expedition had traveled.

While Peary’s claim was widely accepted for the majority of the 20th century, Cook’s reputation continued to decline, and he is remembered by history for making up his achievements including the North Pole and the summiting of Denali. However, the writer Robert Bryce believes that Cook, as a physician and ethnographer, cared about the people on his expedition and admired the Inuit. But at the time it was difficult to find financial supporters for such ethnographic missions without a goal that was more flashy. So there was tremendous pressure on both Peary and Cook to be the first to reach the pole, in order to gain continued financial support. Additionally, it was later discovered that Peary’s team had offered some of Cook’s expedition partners for his Denali mission financial compensation for signing affidavits claiming that Cook had lied about his accomplishments. Moreover, Peary’s claim of having reached the North Pole was later discredited by a variety of reviewers, including the National Geographic Society, which long supported him. In both cases, a lack of definitive proof and the stinging attacks by the other turned what should have been each man’s moment of triumph into a petty dispute that lasts to this day. It is not certain whether either man truly reached the North Pole, and - barring new evidence coming to light - the mystery is likely to remain. It would not be until 1968 and the expedition of Ralph Plaisted on snowmobile that we would see the first undisputed overland expedition to reach the North Pole.

"Has simply handed the public a gold brick."

Peary, 1909

"I have come from the pole."

Cook, 1909