Photography

Western Perspective

These two images depict parts of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, which was mentioned earlier, that took place from 1913 to 1918. To recap, Vilhjalmur Stefansson organized the expedition in pursuit to find a continent north of the Canadian Archipelago. Additionally, one of the purposes of this trip was to explore what to the British was an unknown area of land and to achieve scientific knowledge from the area. The expedition was split into the Northern Party and the Southern Party. The Northern Party’s goals were in line with Stefansson’s aim of discovering new land while the Southern Party had the objective to map the Arctic coast from Cape Parry east to Kent Peninsula while making a wide range of scientific observations and collections. Additionally, the Southern Party was tasked with attaining archeological and anthropological studies of the Copper Inuit, and biological studies of mammals, birds, plants, insects, and marine life.

This photograph from the expedition of the Polar Coast of Cape Parry was likely taken from a member of the Southern Party to map out the Coast. This photograph captures the Western perspective of the Coast for scientific pursuit to have an accurate map of the Coast. The image of the coast itself did not come with a description from the archive but still demonstrates an area that was previously untraveled by the British. Though the Southern Party was also tasked with additional goals regarding archeology, this image serves as important to filling in the gaps in the current maps during the 1910s of the Northern regions. With it also being taken during the summer, the state of the Coast during the expedition can also serve as comparisons to what it looks like now due to climate change and expedited melting of the ice in the Northern regions.

The image of stopping for lunch on Barter Island likely also came from the Southern Party, more specifically, from the team under Diamond Jenness who was told by Aiyakuk, an indigenous man, in mid-April, about the ruins of old wooden buildings on Barter Island, which was 50 miles east of the Southern Party's headquarters. This part of the expedition served the archeological purpose as Jenness made a brief visit to Barter Island and also nearby to Arey Island. He found that from the condition of the driftwood logs that some buildings were recent while others were over 200 years old. With the assistance of Aiyakuk and Aiyakuk’s stepson, the team was able to excavate, examine, and sketch the ruins. This image of the stop for lunch conveys the story of the vast ice sheets that covered the island even during the summer, and like the image of Cape Parry, provides an understanding of what the ice looked like in the 1910s. Moreso, like Cape Parry, Barter Island served as an important area of scientific pursuit and conveys this Western ideal of discovery and acquiring scientific knowledge. Rather than focusing on characteristics of the photographer or what is being portrayed, it seems so matter of fact rather than conveying a deeper story of embarking on the Expedition in line with the western lens of the Arctic, and the value it holds.

Indigenous Perspective

After Cutting Up Two Walruses, Igulik (2016) by Robert Kautuk

This photograph helps conceputalize the minute stature of man in comparison to nature. This photograph comes from a drone shot taken by Robert Kautuk of an Inuit hunt for walruses. The mixture of ice, blood, people, and sea blurs the distinction between each party, melding every actor together. This is concomitant with the Indigenous perspective of man as a part of nature, and not separate from it. The blood staining the men, ice, and water also demonstrates the sacredness of the hunt from an Indigenous perspective; taking a life is taboo and destructive, tainting the life around it, and must be appeased by pleasing the spirit of the hunted animal. Additionally, the men, blood, and even the ice being dwarfed and closed-in by the sea around it demonstrates the power of the Arcitc. Kautuk did a wonderful job framing this photograph; the height above the people and the scale create this powerful and imposing aura. Despite the power and hardships of nature which are so apparent in the Arctic, Indigenous people are able to survive in such a harsh environment by respecting the power of nature. Indigenous people are able to understand the natural world of the Arctic using their traditional ecological knowledge passed down through generations, and yet also adapt to the changing times, as shown by the motorized boat. Therefore, this photograph portrays man’s intrepid spirit, resilience, and respect for nature.

The Uncertainty of the Seasons (2021) by Holly Anderson

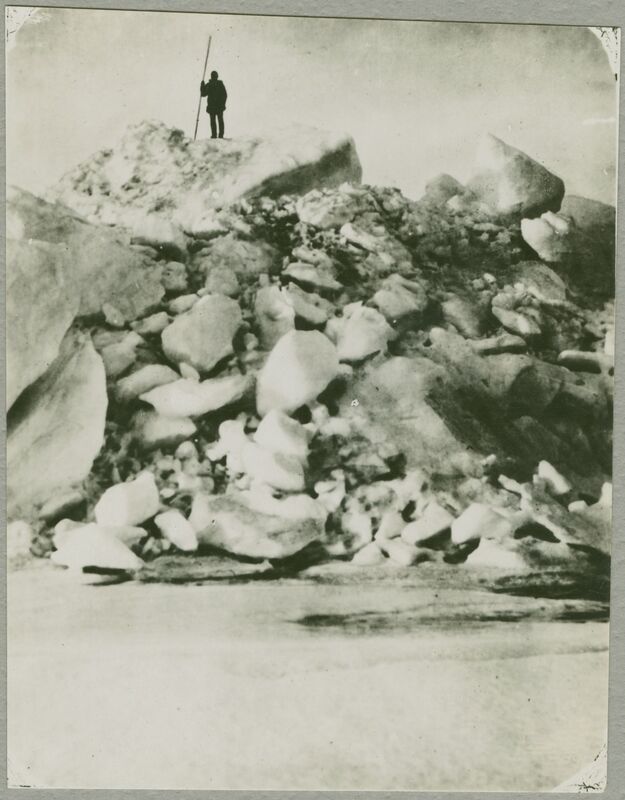

Man on Heaved Ice by Vilhjalmur Stefansson

This first photograph on the right by Holly Anderson shows an Inuit hunter standing on top of an icy and rocky cliff, overlooking the bay. He has some sort of firearm on him. He demonstrates the conquering power of man over the natural world. He has summitted and now literally stands above the ocean and ice below him. Oftentimes, man’s hubris leads to significant failures dealt by the natural world. However, man also has an undying spirit to achieve success, as represented by the man in the photograph. Indigenous people, while respecting the environment, have also been able to survive by becoming masters of their environment. The ability to integrate traditional ecological knowledge with adaptation has allowed Indigenous people to live in such an inhospitable environment for so long. This person could have just been posing, or could have sumitted the ice for a better view. This ice is both an obstruction and a vantage point, depending on how it is used. It is interesting that the man uses a gun, but this poitns to the changing times in the Arctic in which hunters have adapted to the latest technology.

This photo was chosen because it is in direct contrast to a photo by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, on the right below the first photograph, showing a man standing atop of a pile of heaved ice. This “heaved ice” or ice shove, develops when there is a surge of ice from an ocean or large lake onto the shore. This huge pile of heavy ice also shows the raw power of nature. These photographs are certainly in conversation with one another. While Stefansson, representing the Western perspective, takes the photo of the man from below, Holly Anderson, representing the Indigenous perspective, takes the photo of the man from the same level as him. These photos demonstrate that the Western perspective of Inuit people is distanced; Western people cannot fully understand the Inuit hunter. The Indigenous perspective, however, is on the same level as the hunter; Indigenous people, even in changing times, are able to understand the ways of life of one another. This photograph portrays man’s undying spirit, our hubris concerning our power over nature, and the ability for nature to help us see over obstacles. Perhaps to overcome the difference in photographs and cultures, we must begin seeing one another more eye to eye.

Sources:

Western:

Andrews, John. 2012. “Stefansson, Dr Anderson and the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–1918. A Story of Exploration, Science and Sovereignty Stuart E. Jenness . Gatineau, Quebec, Canada. Canadian Museum of Civilization, Mercury History Paper. 56 2011. 415 Pp. $39.95 (Softcover). ISBN: ISBN 978-0-660-19971-9.” Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 44 (February): 151–151. https://doi.org/10.1657/1938-4246-44.1.151a.

Jenness, Stuart E. 1990. “Diamond Jenness's Archaeological Investigations on Barter Island, Alaska.” Polar Record 26 (157). Cambridge University Press: 91–102. doi:10.1017/S003224740001113X.

Khidas, Kamal. “The Canadian Arctic Expedition 1913-18 and Early Advances in Arctic Vertebrate Zoology.” Arctic 68, no. 3 (2015): 283–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43872247.

“The Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913-1918) – Beaufort Gyre Exploration Project.” n.d. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www2.whoi.edu/site/beaufortgyre/history/the-canadian-arctic-expedition-1913-1918/.