Religious and Spiritual

Western Perspective

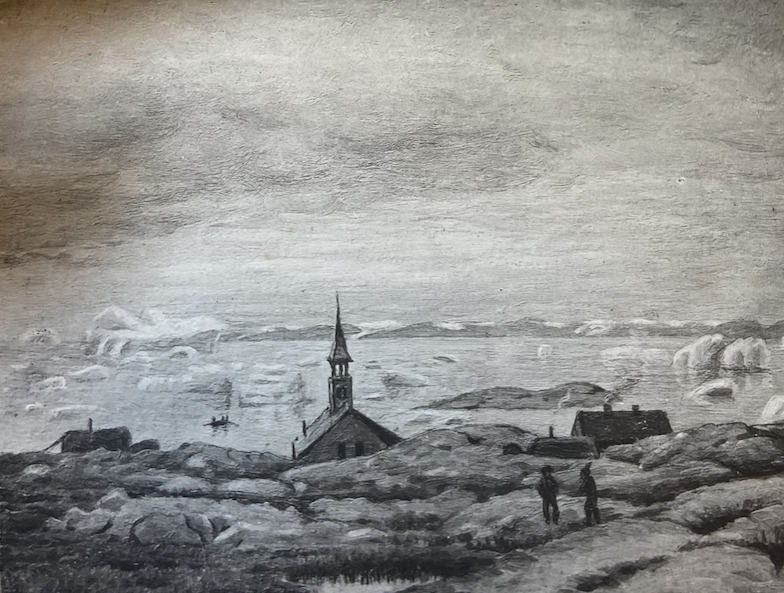

Here we can see a depiction of a church in the Greenland landscape overviewing the Jacobshavn Glacier. This sight sparks in Andreas Carstensen a moment of reflection on the Christianization of the indigenous people of the area. He says, "To what extent these people were true Christians I am unable to state, but I am inclined to believe that a large majority really were pious, and I am convinced that they all were happy at the disappearence of the ancient state of affairs," (141). Through this drawing, we can see, at least through the eyes of Carstensen, that the church and Christianity are a focal point in the community. He says that all indigenous traditions have been dropped and supplanted with customs from the Danes. And apparently this seems to be a joyous and consensual process. This drawing and accompanying passage emphasizes the theme of the white colonizer "saving" indigenous peoples from ancient and outdated customs and ways of thinking and modernizing them for "their" benefit. In the drawing we can even see an Inuit man talking to a Westerner and this image truly reinforces Carstensen's belief of this amicable partnership between the two communities and the Westerners partaking in "God's work." By viewing this art once it was published, the Western world would believe in an amicable relationship between the two parts of the world which would further justify the missionary work being done.

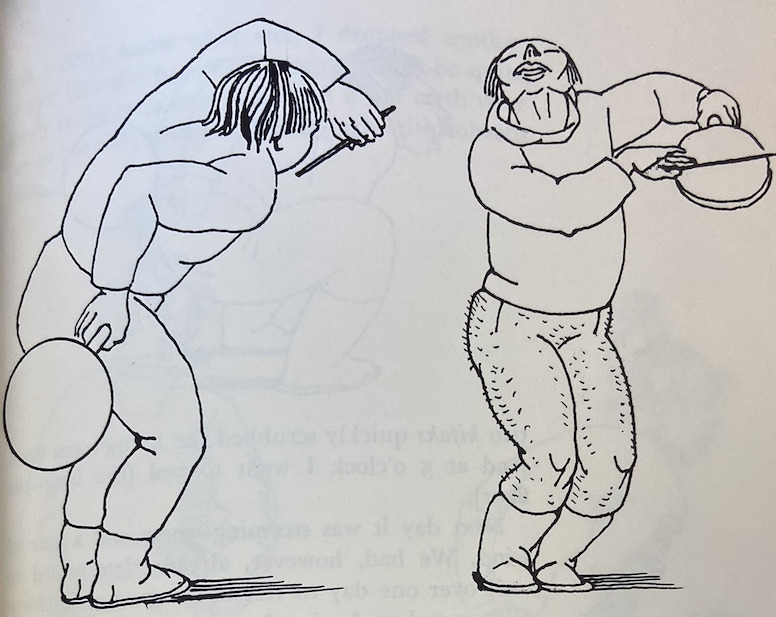

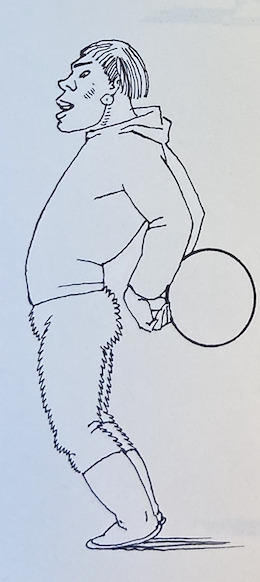

Here, we see two illustrations from Rockwell Kent's journal of an impersonal Inuit man performing a traditional dance with a drum after dinner. The manner in which Kent describes this scene makes it seem very much like a spectacle, as if he were watching a circus act. The reader can easily pick up on Kent's amusement through descriptions like, "Three old men of Nugatsiak including Peter Ottisen danced again and again. Magnificent! One young man was wildly spirited. He was, however, like an actor who overdid his part," (199). Lacking from his descpritions, however, are any meanings of the dance. It appears that Kent truly took the dancing as a form of entertainment as opposed to learning about the history of the dance or why they do it in the first place. We can really see this disconnect between the white Westerners and the indigenous peoples in these ceremonial scenes and how the Westerners view these communities as primitive. On a separate night, Kent describes one of the dancing women as a "homely, slovenly creature," which really drives home the trope of colonizer and colonized (185). The art itself seems to be just sketches, so we cannot really speak to whether we think this is how Kent truly saw indigenous people or believed them to be. However, the descriptions of these scenes showcase the overarching idea of how Westerns viewed indigenous customs to be ancient and mystic and used them as a scientific endeavor.

Indigenous Perspective

This image is a color illustration depicting an Alaskan Inuit folk tale. In the story, two siblings are eaten by wolves and afterwards transformed into caribou. The tale was collected and inscribed by Knud Rasmussen on an Arctic American expedition in the 1920s.

The tale of the children being transformed into caribou demonstrates the Inuit belief in animism -- that every being, human or not, possesses a spirit. This theme is important in many Inuit spiritual tales. Many legends describe humans being turned into animals. For example, the sea goddess Sedna was said to be a girl turned into a half-human, half-fish creature. Life for the indigenous Arctic peoples is reliant on animals for all things -- food, clothing, shelter, and many other uses. Animals were also an ever present threat, as demonstrated in the tale illustrated in the image. The strong connection to animals and the land in general are evident in the oral tradition.

Another aspect of Inuit spirituality which is exemplified here is that of the oral tradition. This illustration was not created by an Inuit person, but rather an explorer capturing the tale on his travels. Oral tradition is the primary medium through which vital knowledge, spirituality, and history are relayed through generations of Inuit people. The translation of the folktale into image contributes a more readily comprehensible version to outsiders, allowing a glimpse into the vibrant spiritual traditions of Inuit peoples.

This sculpture depicts the Inuit goddess of the sea, Sedna. It was crafted by a Canadian Inuit person. Carved out of stone, this sculpture depicts the half-fish, half-woman figure held among the most important deities of the Inuit peoples.

Part of the rich oral history of the Inuit peoples, stories of the sea goddess have been passed down through generations. As such, details about the goddess are fluid and vary from source to source. What is held in common is Sedna's primacy within the Inuit pantheon. Sedna controls all sea creatures and is half-woman, half-fish. Sedna was not always a deity, though -- she was once a human girl, but thrown into the sea under unfortunate circumstances. She is there transformed into the half-fish, half-woman figure that the Inuit believe controls all sea creatures. The Inuit dedicate songs and offerings to please the goddess and, hopefully, invite her blessings for a bountiful hunt.

This piece again exemplifies the importance of animism, the profound connection between Inuit people and local animal life, and the passing on of stories through oral tradition. It also gives direct insight to the conceptualization of Sedna through the eyes of local peoples.

Sources:

Carstensen, Andreas Christian Riis. Two Summers in Greenland : an Artist’s Adventures Among Ice and Islands, in Fjords and Mountains. London: Chapman & Hall, 1890.

Stef G742 .C32

Rockwell Kent. Rockwell Kent’s Greenland Journal. 1st ed. New York: I. Obolensky, 1962.

Illus K418keg

Stefansson, Vilhjalmur, 1879-1962. Eskimo girl in flames with a caribou leaping overhead, 1906. Digital by Dartmouth Library. https://n2t.net/ark:/83024/d4v97zx0n.

Inuit, Canadian. Sedna, the Sea Goddess, 20th century, small stone sculpture, Dartmouth Hood Museum. https://hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu/objects/168.94.24428.