Command and Craft: Contrasting Antarctic Perspectives

Richard E. Byrd's Published Book, Little America

Byrd’s published account of his 1928 Antarctic expedition provides readers with an overview of the trip’s timeline and the Antarctic landscapes the crew encountered. While Mulroy writes mainly for himself, Byrd is clearly writing for a larger audience. His text focuses less on day-to-day life than Mulroy’s diary, with Byrd instead writing in a more narrative style that directly speaks to members of his audience and connects his decisions and actions to his larger goals for the expedition.

In his book, Byrd makes it clear that he is writing for the people who funded his trip. The Foreward that opens the book lists and thanks the main donors. Byrd lists a lot of high-profile names, including the Rockefellers, Fords, American Geographical Society, and National Geographic Society, demonstrating both Byrd's connections and the importance of his expedition to the public.

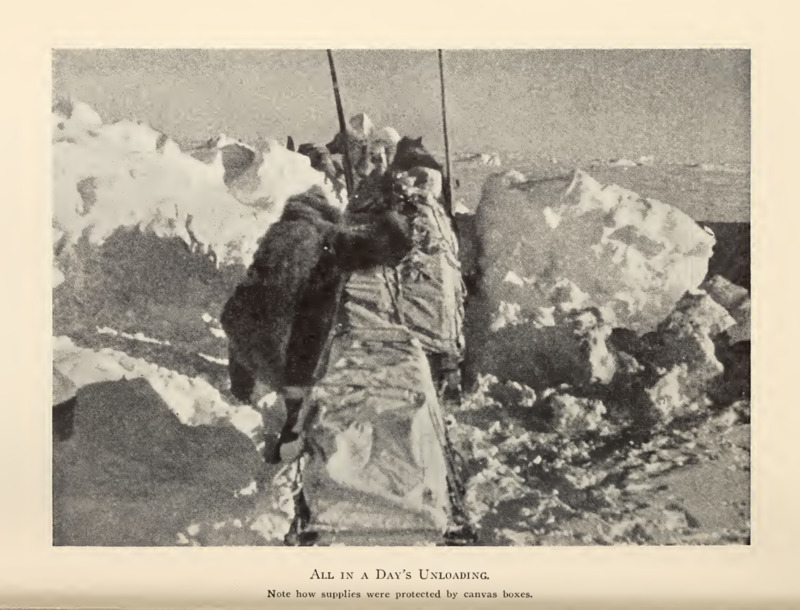

This Antarctic expedition is known for how expensive it was. Byrd took several ships, planes, and sleds, as well as enough fuel and food to support his large crew. In his journal, Byrd mentions leaving for Antarctica in debt. As a result of the significant financial contributions Byrd received, he dedicated large portions of his book to detail the process of preparing for the journey. He describes bringing “over 500 tons of supplies and material; there are at least 5,000 different kinds of things… and every single thing is essential” to ensure the survival of his crew in harsh Antarctic conditions (p. 3). The sheer amount of equipment Byrd carried with him likely was extremely beneficial. Even though he wrote about having to carefully ration items such as food, especially towards the end of the expedition, Byrd’s crew did not have to contend with any severe shortages of supplies that other failed polar expeditions experienced.

The message of gratitude that opens the book is reflected in its conclusion, where Byrd establishes the need for future Antarctic exploration, establishing the reasoning to imply that expeditions should be funded in the future to advance scientific discovery. Byrd writes:

"There is the wish also to put an end, once and for all, to the journalistic practice of referring to our efforts as the 'conquest' of the Antarctic. The Antarctic has not been conquered. At best we simply tore away a bit more of the veil which conceals its secrets. An immense job yet remains to be done. The Antarctic will yield to no single expedition, nor yet to half a dozen. In its larger aspects, it still remains, and will probably remain for many years to come, one of the great undone tasks of the world." (p. 392)

Hardship on the Journey

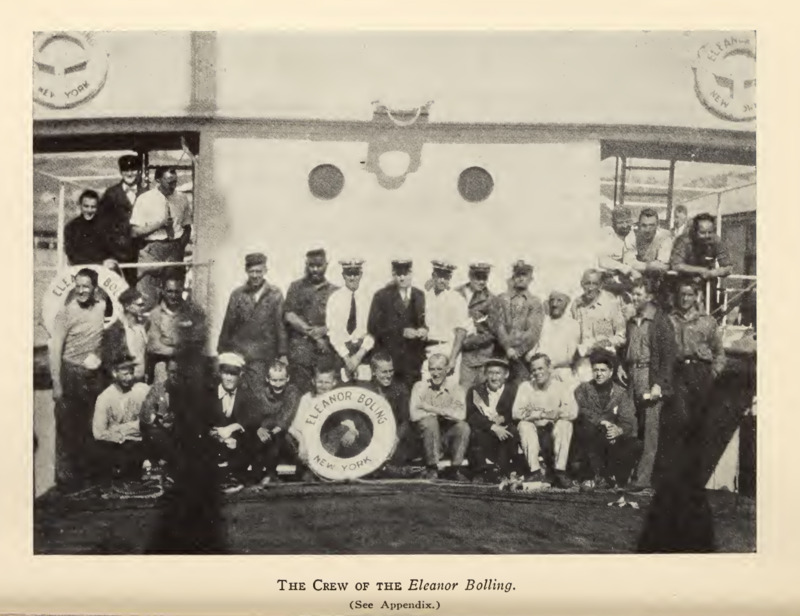

Throughout the narrative, Byrd generally maintains a more positive attitude than Mulroy, glossing over the challenges faced by the crew. However, he does not deny that the trip was extremely difficult at times.

Sometimes Byrd’s description of the harsh conditions reflects Mulroy’s, more openly acknowledging his crew’s struggles. For example, when the expedition party stops in New Zealand before heading South to Antarctica, Mulroy describes the extreme heat in the engine room, even commenting that it had caused him to lose weight. Byrd’s testimony also mentions this, writing that the crew described the engine room as “‘Hell’s anteroom,’” with “decks that sizzled at noon and fire room temperatures that got as high as 1200 Fahrenheit.” (p. 50) However, as the captain, Byrd’s main concern seems to be whether his crew was fit to continue their journey, explaining:

"I was delighted to observe that the crew as a whole had come through very well, the greenhorns had become accustomed to their various duties, and Captain Brown's ability was plainly marked in the high morale of his men." (p. 50)

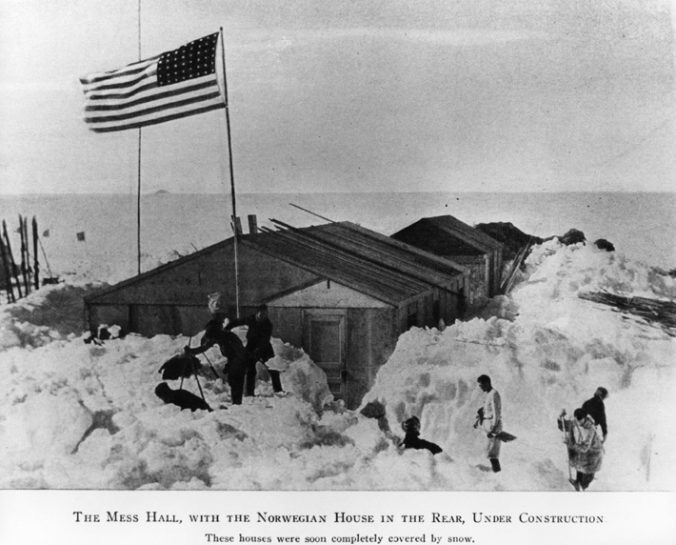

Once in the Antarctic ice, Byrd frequently describes the difficult labor required of his team, especially throughout the process of setting up Little America and reinforcing the camp against the harsh weather conditions. He writes about the sheer amount of work that went into building the camp and preparing it for winter, saying:

"What busy days they were! And yet not a few of us found them to be happy ones. We met the advancing winter with a great show of industry and the satisfaction that well-ordered and effective labor brings." (p. 158)

Although Byrd is eager to detail the hardships faced by his crew in order to glorify the group’s accomplishments, he maintains a much more positive tone than Mulroy, who was actually performing many of these more difficult tasks himself.

Morale

Byrd frequently mentions crew member relations throughout his book; however, his evaluations largely focus on morale and how it influences his team’s ability to work together to accomplish the shared goals of the expedition. Over the winter, Byrd does mention some “passing irritations,” “most of them mild, a few intense” among his crew (p. 238). However, otherwise his descriptions of crew relations were overwhelmingly positive. Like Mulroy, Byrd explains that meals were an important time for crew members to bond, writing:

“The period that followed supper was always—or nearly always—a delightful time. The dishes were pushed aside, pipes came forth, cigarettes were lighted, and men remained to chat or drifted off to join the groups in other buildings.” (p. 207-208)

Food seemed to play a significant role on the Byrd Antarctic Expedition as a means of bonding the crew together. Holidays were emphasized in the Byrd narrative, as he explained that dinner menus were made more elaborate in order to boost morale and provide a break from the difficult work of the expedition.

Throughout his writing, Byrd clearly considers loyalty to be the most valuable trait among his crew. He writes:

"There is only one thing holding us together, disciplining us, identifying us from any other collection of persons on the high seas. It is the fact of loyalty. Loyalty not only to a common purpose; but loyalty according to the various ideals we live by: loyalty to family, to country, to men, even to self, and to God. In this affinity I place my hope. There is no other bond on earth save this that will see men through an Antarctic winter night and the other experiences that lie ahead of us." (p. 21)

In the face of setbacks, Byrd clearly values his crew’s dedication to himself and the expedition among all else. He repeatedly mentions how grateful he is for their hard work and the risks they take in order to ensure that exploration parties are successful, suggesting a more personal connection to the men who worked for him.

Sources:

Byrd, Richard Evelyn. Little America: Aerial Exploration in the Antarctic: The Flight to the South Pole, (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1930), Retrieved from https://ia600300.us.archive.org/20/items/littleamericaaer00byrd_0/littleamericaaer00byrd_0.pdf.

Hooton, John. "Frozen Fridays: ‘L’ is for Little America!." The Ohio State University: University Libraries. February 3, 2017, https://library.osu.edu/site/archives/2017/02/03/frozen-fridays-l-is-for-little-america/.

"Lot #92622." Heritage Auctions: The World's Largest Collectibles Auctioneer. Accessed November 20, 2024, https://historical.ha.com/itm/books/non-fiction/richard-evelyn-byrd-little-america-aerial-exploration-in-the-antarctic-the-flight-to-the-south-pole/a/684-92622.s.

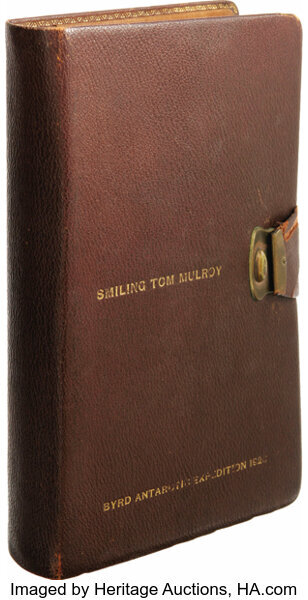

Smiling Tom Mulroy's Diary

While Byrd’s account of the 1928 Antarctic expedition reveals the scientific discoveries and achievements that the expedition accomplished, Mulroy’s diary tells a more emotional story, revealing the thoughts behind the people aboard the ship. Even though Mulroy’s entries start as matter-of-fact descriptions of weather and conditions, the later entries reveal his true disposition and the changing state of the men on board. On the eve of their departure, August 25th, Mulroy writes with excitement:

"Well here I am again starting out on another great adventurous trip to the South Pole with 70 souls including Comdr Byrd…"

Yet, over time, the entries grow more solemn and dejected. By February, almost six months after the expedition began, Mulroy writes:

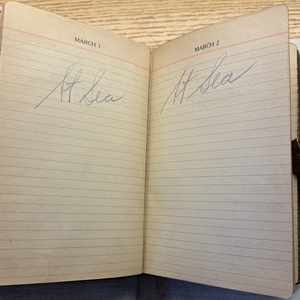

“Well another month…just making time…it’s the same old talk about getting out…”

By March, many of Mulroy’s entries simply read, “At sea,” alluding to his frustration, the repetition of the days aboard the City of New York, and the unsatisfactory life of a crewman in general. Further, Mulroy gives an inside view into life as an engineer, responsible for making the ship run as expected. The engine room, as he describes it, was hot and unbearable.

Happier Times

Mulroy’s diary also gives us insight into the daily life of other people—both on board and in the traveled areas—that Byrd’s book doesn’t detail. When the ship reached New Zealand, Mulroy writes about his positive interactions with people there, writing “In Dunedin having a hell of a good time. It seems like the people of New Zealand can not do enough for us.”

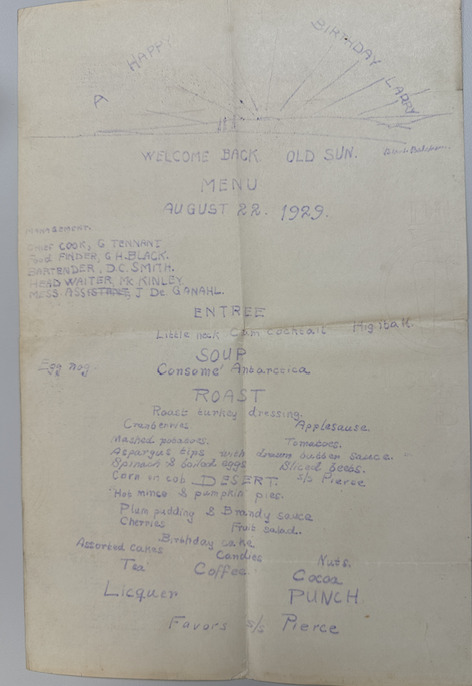

Relationships among crew members are also revealed within Mulroy’s diary and other materials. For example, Mulroy wrote a menu for crew member Larry’s birthday on August 22, 1929. The menu was complete with appetizers, soup, meat, dessert, and drinks, as well as birthday cake. Roles such as waiter and bartender were assigned to other members of the crew. Items such as these reveal important aspects of the daily life of crew members. It displays the ways in which members of the expedition made the best of tough circumstances, as well as humanizing the expedition beyond Byrd’s writing.

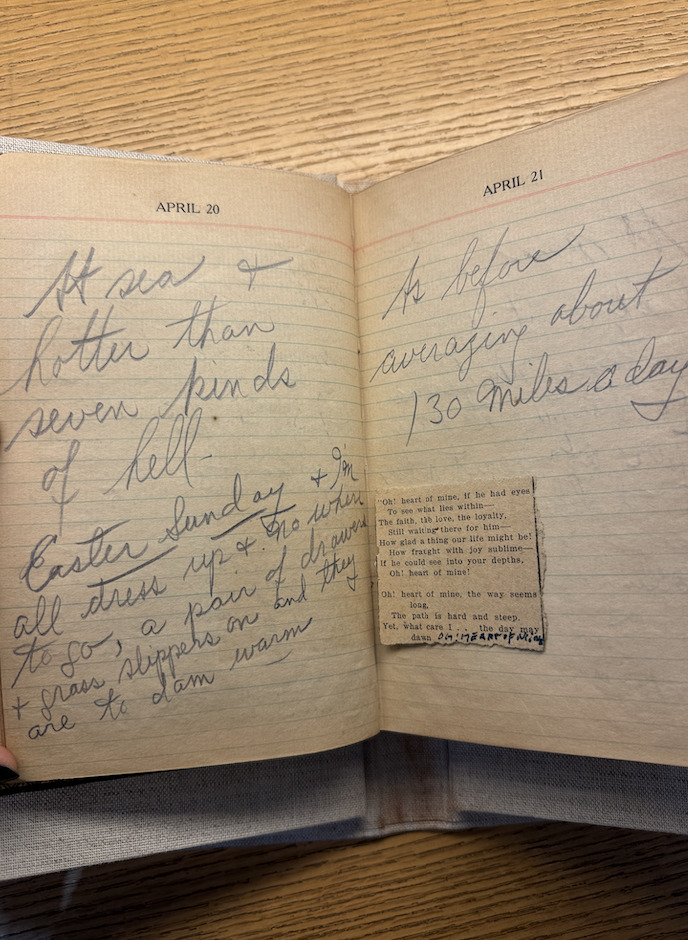

A prime example of this juxtaposition—of tough conditions with a human spirit—is in one of Mulroy’s entries from April. The entry reads “At sea + hotter than seven kids of hell.” Tucked into the page of the journal, however, is a small piece of paper, an excerpt of a poem.

“Oh! heart of mine, if he had eyes

To see what lies within–

The faith, the love, the loyalty,

Still waiting there for him–

How glad a thing our life might be!

How fraught with joy sublime–

If he could see into your depths,

Oh! heart of mine!

Oh! heart of min, the way seems

Long,

The path is hard and steep.

Yet, what care I…the day may dawn”

Written in pen on the end of the bottom of the paper is “Oh! Heart of mine.” Tucked away within excerpts depicting hard days at sea and a kind of hopelessness, is an annotated scrap of poem, giving us an insight into the person behind the journal. Mulroy’s writing goes a step beyond Byrd’s account of the expedition, providing insight into the daily experiences of someone with a lower rank than the commander. Instances such as these—with Mulroy’s most raw thoughts, the people he was meeting, and the things he read to keep him sane—paint a more complete picture of the Antarctic expedition, a story that one might not when just considering the science.

Comradery

Mulroy writes often about the other men, crewmembers, and scientists aboard The City of New York, making it clear that he holds a distinct importance in the friendships and relationships he builds while on the Antarctic expedition. While aboard the expedition, Mulroy celebrated many milestones, both related to the expedition’s mission and more personal in nature—like Easter, as he mentioned in his April 20th, 1929 entry.

One such event is the birthday of fellow crewmembers aboard the ship. On August 22, 1929, the crew celebrated the birthday of their coworker Larry. Mulroy scribed a dinner menu to celebrate the occasion, listing local foods, such as “Consomé Antarctica.” They selected dedicated members of the crew to serve as Chief Cook, Food Finder, Bartender, Head Witer, and Mess Assistant. The menu features a mention of egg nog and liquor.

In addition to celebrating the birthday of Larry, the menu also writes “Welcome Back Old Son,” potentially highlighting the celebration of good weather. The dinner menu reveals the foods that made the crew feel most at home or celebratory, their happiness in welcoming the sun, and a glimpse into the ways in which they created their own comradery while aboard. The menu has jokes, revealing their shared enjoyment and humor with each other and revealing the close-knit relationships that were formed a year after the expedition began.

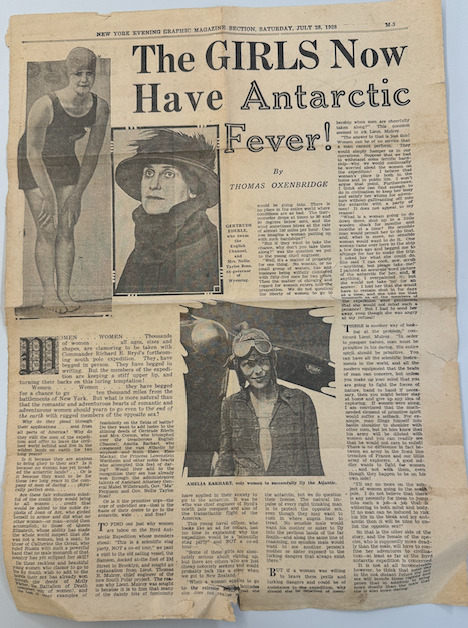

What About Women?

Mulroy’s description of the expedition portrays a sense of comradery among the men aboard—at once a shared suffering and a shared human experience of small joys. Yet, it’s important to consider the impact of gender on involvement in Polar research. In an article titled “The Girls Now Have Antarctic Fever!” Thomas Oxenbridge interviews Thomas B. Mulroy ahead of the 1928 Antarctic expedition.

Mulroy explains that the expedition is not a place suited for women, saying that “When a woman applies to go to the extreme south latitude she does not realize what she would be going into.” He follows up by saying “Women can be of no service that a man cannot perform. They would simply hamper us in our operations.” In the 20th century, women who had strong desires to be a part of Arctic and Antarctic research were again and again denied access, for reasons similar to what Mulroy expressed. Yet, women were often behind-the-scenes contributors to research and the success of expeditions. While Mulroy’s writing gives us an important insight into the brotherhood and comradery created aboard the City of New York, it’s necessary to understand that this community was created with the deliberate exclusion of women.