A First Person Account: the Journal of John Wiseman

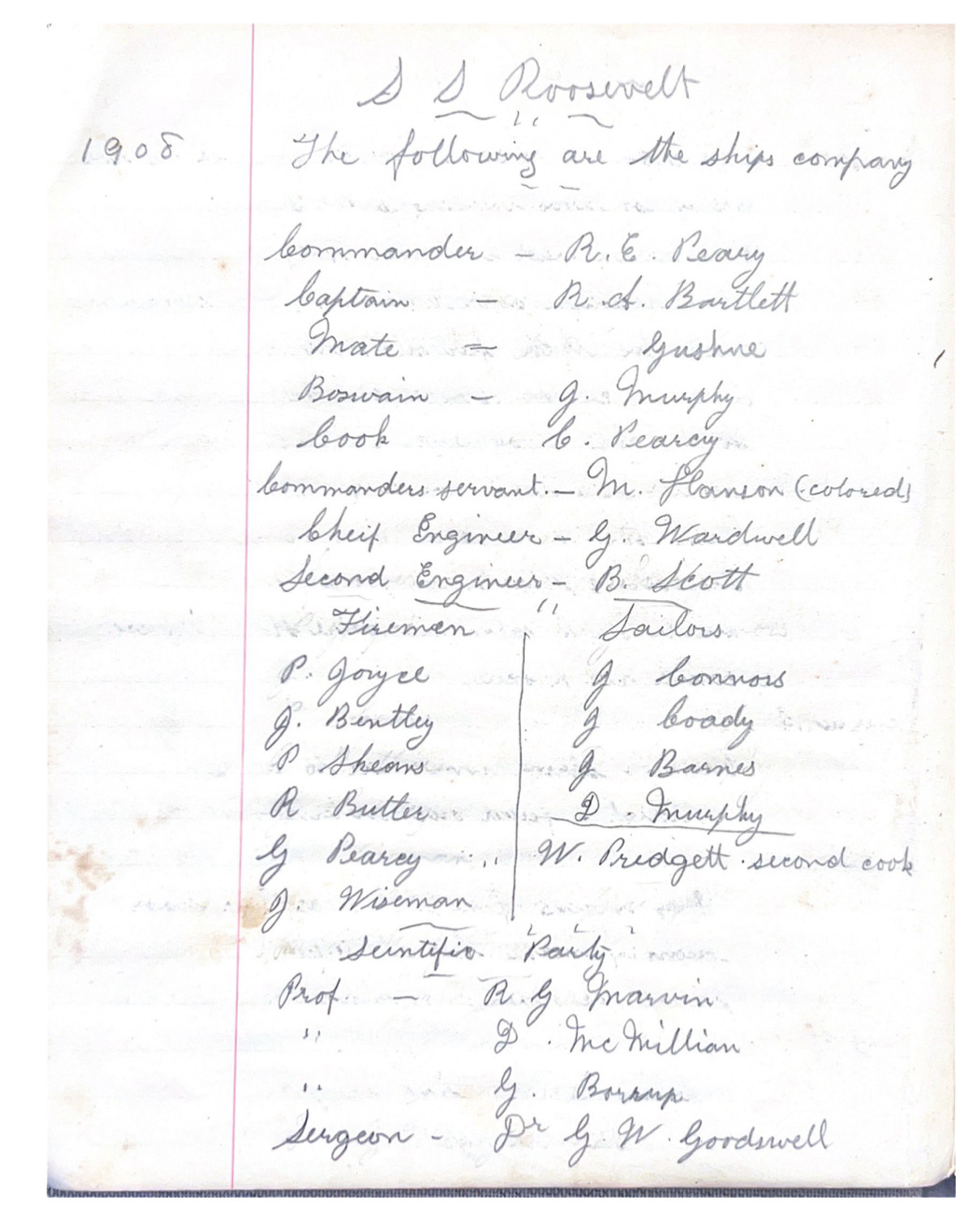

John M. Wiseman was one of twenty-two men who originally set out on the expedition. Along with James Bentley, Patrick Joyce, and Patrick Skeans, Wiseman acted as a fireman on board the S. S. Roosevelt. Though he was not a well-known figure on the expedition, he did play an important role in keeping the ship up and running, allowing the expedition to reach the far north. Wiseman kept a journal throughout the expedition, in which he wrote entries almost every day. The majority of his entries lack personal commentary, usually describing weather conditions, ship updates, where they sailed that day, and who ventured into the cold to research or hunt. Not all of his entries were mundane; Wiseman’s journal offers an important first person perspective of the expedition. He includes important remarks on Marvin’s death, Indigenous presence in the expedition, and Peary's controversial reaction to returning from the Pole

Before starting their journey to Greenland, the ship docked in Oyster Bay where the President of the United States boarded the ship and sent them off. Theadore Roosevelt was president at the time and each member of the crew got to shake his hand as he wished them a successful journey. The president's presence highlights the importance of this trip to the country. This was not the only government official that the ship interacted with, as Wiseman notes that “the governor” also gifted them whisky and wine.

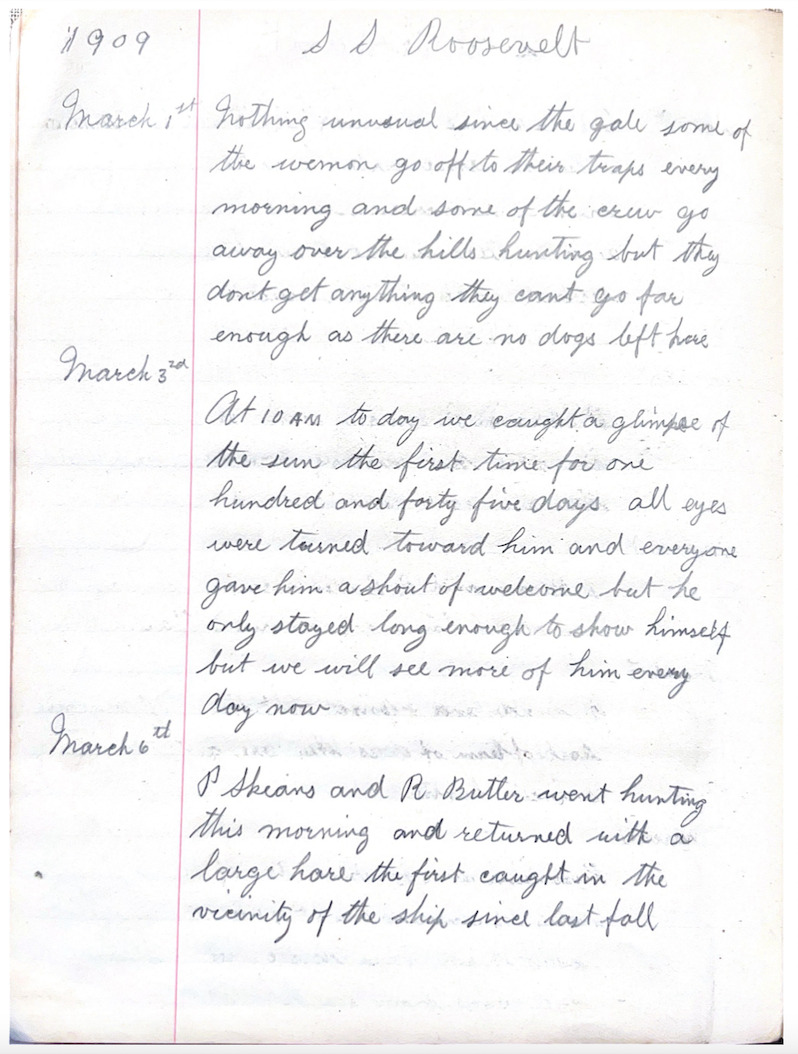

This expedition was not an easy journey as there were many physical and mental challenges present throughout its entirety. For example, the crew was in complete darkness for 145 days. Wiseman describes the first time they see the sun as a very special and momentous occasion for the entire ship; his entry of this day can be seen in Figure 1.

Within the challenges, there were moments of fun and excitement. On Christmas day, the crew delighted in festivities: they drank the twelve bottles of whisky and twelve bottles of port wine from the governor, smoked pipes, ate chocolate, and played games of strength (like tug of war and foot races) with the officers.

John Wiseman was brought onto the ship as a Fireman, but his journal shows that he gained more responsibilities as the journey continued, specifically, receiving tasks from the head scientist, Ross Marvin. Wiseman’s entries describe a teacher-student relationship between him and Marvin. Marvin appeared to take Wiseman under his wing, teaching him how to take tidal records and bringing him on scientific expeditions. Wiseman describes the time when Marvin and him lived in an igloo for 50 days at the Black Horn Cliffs, taking tides before the “dash to the north pole.” He noted that the igloos were less comfortable than his bunk, but good for the circumstances.

After hearing of Ross Marvin’s passing, Wiseman wrote a detailed journal entry explaining the accident and the crew’s reactions. His proximity to Marvin offers a very personal note on how his death impacted the journey. On April 17th, 1909, Wiseman writes:

“Kudkuebtoo and Harrigan arrived today from ice fields at 11 PM and plunged the whole ships company in deepest grief with the news of Prof R. G. Marvins death by drowning. He fell through the ice while crossing a lead about 40 miles from land they were coming back after leaving the commander in 86°. 30° N the sad accident happened on Easter Saturday the condition of the ice would not allow the huskys rescuing the body when he had fell through and when it was bearable the body had sunk into the icy depth of the Arctic sea we shall feel it keenly as he was a favorite with all on board.”

Everyone on the ship was deeply saddened by the scientist's passing. Wiseman notes that Captain Bartlett was especially affected by Marvin's death, as they were the best of friends. He also mentions an interaction he had with Captain Bartlett after Marvin’s death, where Bartlett said that Marvin expressed plans to take Wiseman on more scientific expeditions.

Wiseman’s journal also creates a new and interesting perspective on the success of the expedition. He notes each man’s departure to the pole (both those there support and those who actually made the whole journey). They all left on different days and brought sleds, dogs, and “huskys” (a word to describe those native to the Arctic) with them. Wiseman states that John Peary left for the pole on February 22, 1909 and returned on April 27th. Wiseman writes that upon his return, Peary walked back to the ship with a smile on his face, but that he “wont say weather he was successful or not but we know that he would not be back already if he was not”. Wiseman also was tasked by Marvin to help sew the clothes Peary wore on his expedition to the pole!

Wiseman’s entries include frequent mentions of “Esqumause” or “huskys” aboard the ship. This suggests that Indigenous people were present throughout the entire journey and had a larger role in their success than historically believed. Whether it is the “20 men and 14 women beside several children” that joined them in their travel up north, or the many “huskys” that supported them by hunting and throughout Peary’s dash to the pole, Indigenous people were present for this historic expedition, and John Wiseman’s journal allows us to see this clearly.