Moving in Stride: Anxieties & Upbringing in the South

Tripp’s story begins with the story of his mother, Edith Jeter, whose passions and values greatly influenced Tripp’s adolescent life. Bold and daring in character, Edith grew up in Queens, New York, but would move several times in pursuit of greater economic and educational opportunity. Her willingness to pick up and move from place to place defined Tripp's childhood, as did her proclivity towards acting and disregarding certain rules. And though Edith never "struck it rich," so to speak, she managed to provide a solidly middle-class upbringing for her son. For much of her own professional life, Edith was an educator. After receiving her bachelor’s degree from Tuskegee University and her master’s degree from New York University, she taught physical education in Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, and Massachusetts.

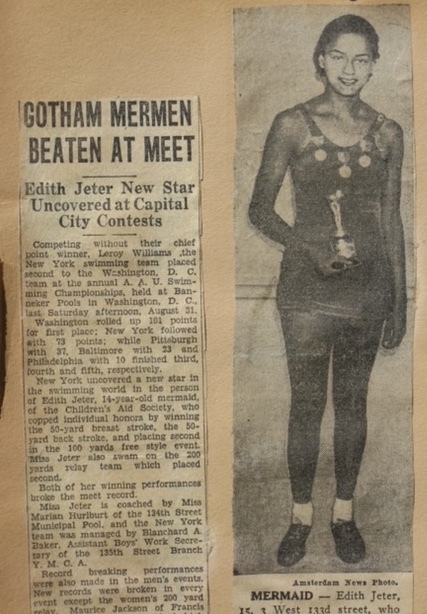

According to Tripp, at a young age, Edith was taken in by a “second parent” who came to make a successful swimmer out of her. By age fifteen, Edith had won two national AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) titles for swimming, one in the breaststroke and the other in freestyle. Despite her impressive performances, which earned her recognition in the Amsterdam News, universities at the time would not reach out to recruit Black swimmers. Still seeking opportunity, Edith enrolled herself in Tuskegee University right around World War II, having completed a year at Hunter College in New York. At Tuskegee University, she met Tripp's father and her future husband, Oliver O. Miller II.

In 1944, Edith and Oliver moved to Battle Creek, Michigan. Around this time, Edith and Oliver had their son (and subject of this exhibit) Oliver Otis Miller III. However, after three and a half years of marriage, the two split, unable to overcome differences in outlook:

"She had a degree, and he didn't. And he had no interest in going to get a degree, 'cause he wanted to be a truck driver. And that disappointed my mother, so after three and a half years of marriage, she divorced him and went back to New York City with me."

Tripp Miller

Edith returned to New York City with Tripp in order to pursue her master’s in physical education. As she attended university, Tripp's grandmother took care of him. Ever active and forthright in her disdain for racial discrimination, Edith participated in protests in Harlem and advocated against unequal treatment of Blacks. After attaining her degree, Edith and Tripp moved south to Wilmington, Delaware and then to Virginia, where she taught at the Hampton Institute. After one year with the Hampton Institute, Tripp and his mother moved to Durham, North Carolina, where Edith accepted a better offer to teach at North Carolina Central University.

Tenacious Genes

Warning: Second slide contains disturbing image.

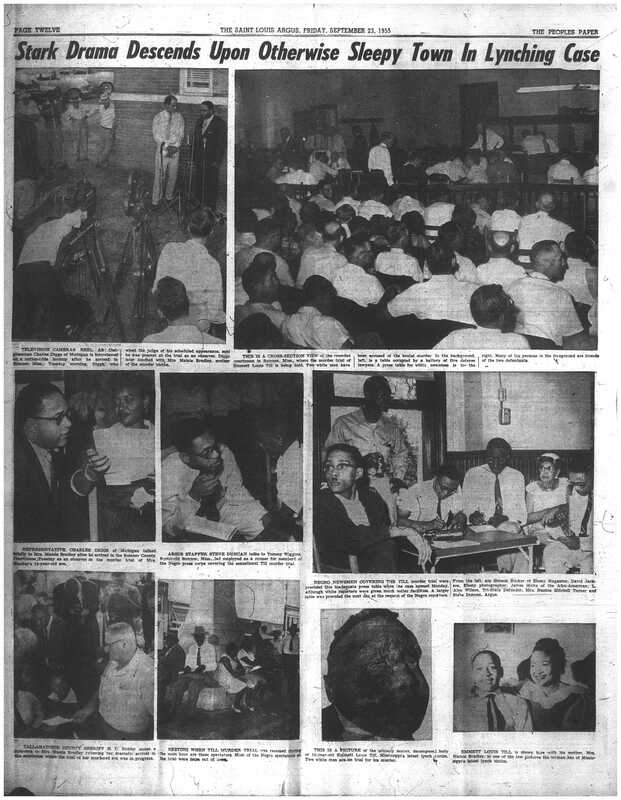

For Tripp, moving to the south with his mother brought on a host of anxieties. For one thing, institutions in the south were segregated at the time, despite the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision. From schools to drinking fountains to waiting areas, a color line still ran throughout the south. These experiences would serve as a reference point for Tripp, who would soon venture back up north to attend high school and college. As Tripp recalls, it was not just the discomfort of being treated as lesser that gave him cause for concern. Rather, it was the safety of his mother that occupied his mind.

Tripp Miller"[Q]uite frankly, I was afraid of going to the south because that was the year that Emmett Till occurred [1955], and it was in all the papers and everything, and I thought that the south was a very dangerous place to live, especially since my mother was the type to maybe not want to follow all the rules, you know. There were white fountains and colored fountains, white bathrooms and colored bathrooms.... And, as I said, I always thought at some time my mother, who had actually protested in Harlem when there was a store where Blacks could buy things, but you couldn't sit at the counter and eat food. And so, my mother was always very forthright about not liking the rules. And as a child I thought sometime my mother might do something wrong and get lynched."

After a few years in the south, Tripp and his mother returned north to New England. This move enabled Tripp to attend non-segregated schools and achieve the highest quality of education feasible in the north. That said, there was one unexpected consequence of his move: Tripp had to leave behind his sixth-grade sweetheart, Jeannette.