Race & Prejudice on Dartmouth’s Campus: Greek Life, Speakers, Diversity

"Needless to say, we [the Black students in the class of '66] all got along very well. And at that time, except for those two fraternities, the student body, I wouldn't say, was prejudiced. And so, I didn't feel like I was in a bad place. In fact, I used to go to other fraternities when they had big weekends. SAE [Sigma Alpha Epsilon] was another southern fraternity, but one of my best friends who was at Dartmouth and also went to Stanford B-School was an SAE."

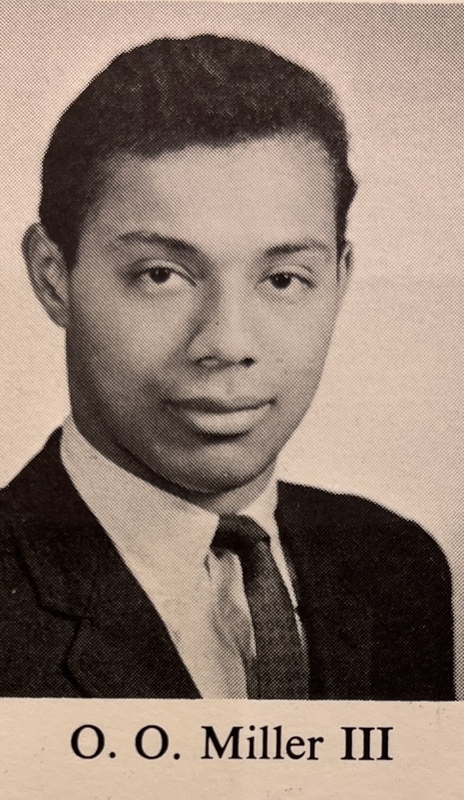

— Tripp Miller

Early Troubles — Fraternity Rush

Entering Dartmouth as a class of ’66, Tripp started taking classes as a sophomore. As per Dartmouth tradition, he participated in fraternity rush his sophomore year as well. Unbeknownst to him, the rush process at Dartmouth was riddled with its own racial dynamics. For one thing, there existed more apprehension among the fraternities at Dartmouth concerning students of color. For another, Black students were expected to only attend rush events at and try to join Jewish fraternities. While at Hamilton, Tripp was a member of the fraternity Psi Upsilon which had a chapter at Dartmouth as well. Typically, a fraternity would accept a brother from another chapter into their fold as a sort of unspoken rule. However, Tripp was “blackballed,” turned away from Psi Upsilon because of his skin color. At the time, there were no internal clauses barring discrimination in the rush process, and so there were no protections against using race to disqualify a student.

Though turned away from Psi Upsilon, Tripp quickly found his place in another fraternity, Chi Phi. Chi Phi had taken such a liking to Tripp that they rushed him and one other Black student, something which could be interpreted as surprising and socially risky, if not unheard of. When asked for his thoughts on the situation, Tripp revealed that he was concerned less about his personal acceptance within the institution and more about his fraternity's reputation. He was interviewed several times by the Daily D about his attitudes on the affair. Fortunately, the situation had a positive resolution: "We were very popular and got some of the best rushing class on campus. So, it didn't work out the way we thought. It was just the opposite." Asked how he views his experiences in a fraternity and at Dartmouth as a whole, Tripp said he looks back upon the experience fondly.

“No. I had a lot of fun because the fraternity was a lot of fun. But we were all concerned [after] they realized that I had been blackballed.”

— Tripp Miller

George Wallace and Malcolm X

As the Civil Rights Movement proceeded in full swing, Dartmouth College worked to expose students to prominent speakers and political figures. Up to this point, there were few protests of any sort that affected Dartmouth's campus. This is unlike schools such as Cornell and Columbia, which were closer to urban centers and perhaps had different racial and political dynamics between the administration and the students, and within the student body itself.

Two major figures came to campus during Tripp's time at Dartmouth. In early May of 1963, pro-segregation Alabama governor, George Wallace, spoke at the College for the first time. Tripp listened to George Wallace over the radio in his dorm, Topliff Hall. Given his experiences in the south, he was interested in hearing what Wallace had to say. A couple of years later in January of 1965, Malcolm X came to speak at Dartmouth in the Spalding Auditorium. Tripp attended Malcolm X's lecture in person.

"Well, the college made sure that we got to see some of the major political figures. So, George Wallace, the famous segregationist, was invited to speak at Dartmouth, and so was Malcolm X. And I was very — I didn't like Malcolm X because I thought he was very radical. But sitting in the auditorium listening to him talk, I was very impressed with Malcolm X. And George Wallace was really funny. He said, "I'm not a racist! Some Blacks come to our social gatherings, and we go to their social gatherings," which having lived in the south, I wasn't impressed, but I was really impressed with Malcolm X."

—Tripp Miller

Tripp's upbringing between the north and the south, his exposure to racism in its different shades and flavors, and his early inclination towards seeking opportunity and mobility granted him a unique view on racial tensions at Dartmouth and in the United States. For much of his life, Tripp (and in particular, his mother) saw and seized opportunities to improve their current position and achieve. Perhaps this is the reason for his nonchalant perceptions of George Wallace and Malcolm X.

The Social Scene

There were twelve other Black students in the class of '66, all of whom knew each other quite well according to Tripp. When asked about his common social circles, Tripp admitted to avoiding rigid social groups and instead maintaining a broad circle. He befriended brothers at Chi Phi, at other fraternities, from his courses as a philosophy major, and generally, any individual whom he considered intellectually engaging or interesting. At his time at Dartmouth, Tripp recalls, race was not a factor he felt occupied much of his thought.

Race did become particularly important in one regard: "The only thing we’re conscious about is there weren’t many Black female students, like at Smith or any of the other colleges that we used to go to get dates.” At this time, Dartmouth was still an all-male institution. Though partly outside the scope of this exhibit, students from Dartmouth around this time would exchange "Pigbooks" with other colleges to find dates. By chance, Tripp had happened to meet another individual from Durham, North Carolina on a bus ride. When he asked her if she had known Jeannette Miller, his childhood sweetheart, he quickly learned that Jeannette attended Elmira College (about two hours away from Clinton, NY, but much further from Hanover, NH). Using these "Pigbooks," he was able to recognize Jeannette and phone her:

"And so, I called her, and she hadn't heard from me in six years. And she screamed, which is a, you know, a girl’s way of telling everybody that she was talking to a potential date."

Tripp Miller

Tripp tapped into some of his connections from Hamilton to see Jeannette as much as he could. Every few weeks, he rode down from New Hampshire with his friend to take Jeannette out on dates. In just a few short years, Jeannette and Tripp would become engaged.