The Tucker Foundation’s Role in Advocating for Student Needs Across the Spectrum of Identity

The 1975 Committee on Equal Opportunity

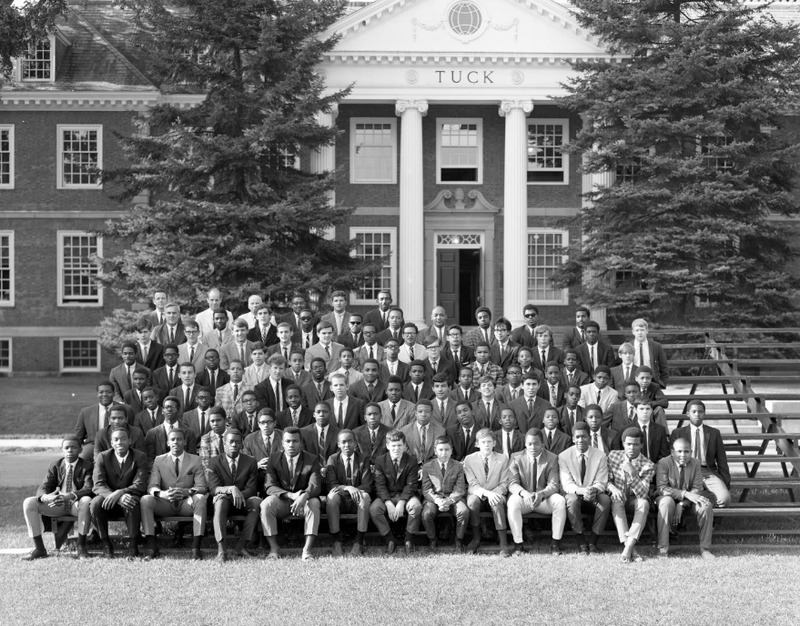

By the time that Traynham returned to campus as dean, a lot had changed since he was a student. The administration put various recruitment measures into effect to increase the diversity on campus. These programs included “A Better Chance” and the Foundation Years project.

“A Better Chance” provided Black high school students with the opportunity to receive tutoring from Dartmouth students, with the hope that those students would then want to later enroll in Dartmouth. The Foundation Years project, on the other hand, provided Black students from urban areas, particularly Chicago, the opportunity to work their way up to Dartmouth courses through a two-year program (Bradley 149–150).

On campus, students had also established the Afro-American Society in 1966 (Bradley 152) and the College had established a Black Studies program in 1970 (Bradley 164). These programs attracted both Black students and Black faculty members.

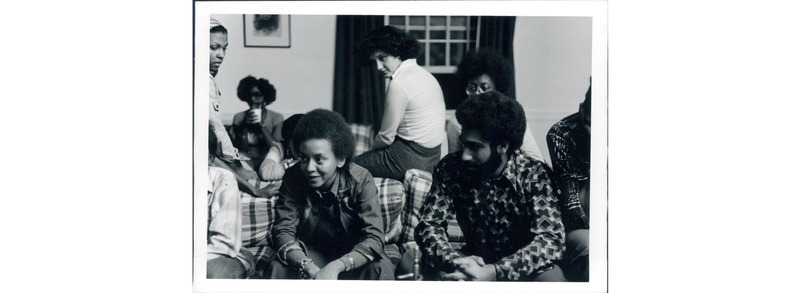

In 1975, the Board of Trustees revisited the issue of diversity and equal opportunity by establishing another committee to evaluate how they could improve upon their policies aimed at increasing the Black student population and enhancing Black student life. One of its main goals was to assess the College’s progress since the issuing of the 1968 "McLane Report," the product of an earlier Trustees’ Committee on Equal Opportunity (Bradley 155, Bradley 162). Traynham acted as chair of the 1975 committee. When asked about his experience on the committee, he said that he admittedly did not remember how successful the committee ended up being, but that his role as chair consisted primarily of listening to student perspectives.

“It is always the case, from my examination of the world I live in, and particularly the country I live in, that once you get a critical number of Black people, you have problems you never had when you only had a few. A few Black people disappear. A critical mass has to be dealt with. I remember the Black tables. When I was the Dean of the Tucker Foundation, invariably, somebody, usually an alumnus or a parent, or sometimes a student, would say things like "why is it that the Black students sit together in Thayer Hall? […] Still, most people, most black people live in Black communities, for reasons which I won't go into at the moment. They come to a predominantly white school. They were still a decided minority when I was Dean of the Tucker Foundation. They get assigned to white students in their rooms. They go to classes, most of which were then still taught by white people — there were many more Black people than before I came, but they still were a minority again. Everything, they're in a white world, you know, and so they have to spend half their time explaining themselves to other people. At some point, they want to be with people they don't have to explain themselves to. That's why there are Black tables.”—Rev. Warner Traynham, 2022

While Traynham admitted that he doesn’t remember the results of the committee's work, he acknowledged that they were “not earth shaking, I don't think. Unfortunately.” To his memory, the conclusions were quite similar to those made by Black students in the report that spurred the committee in the first place.

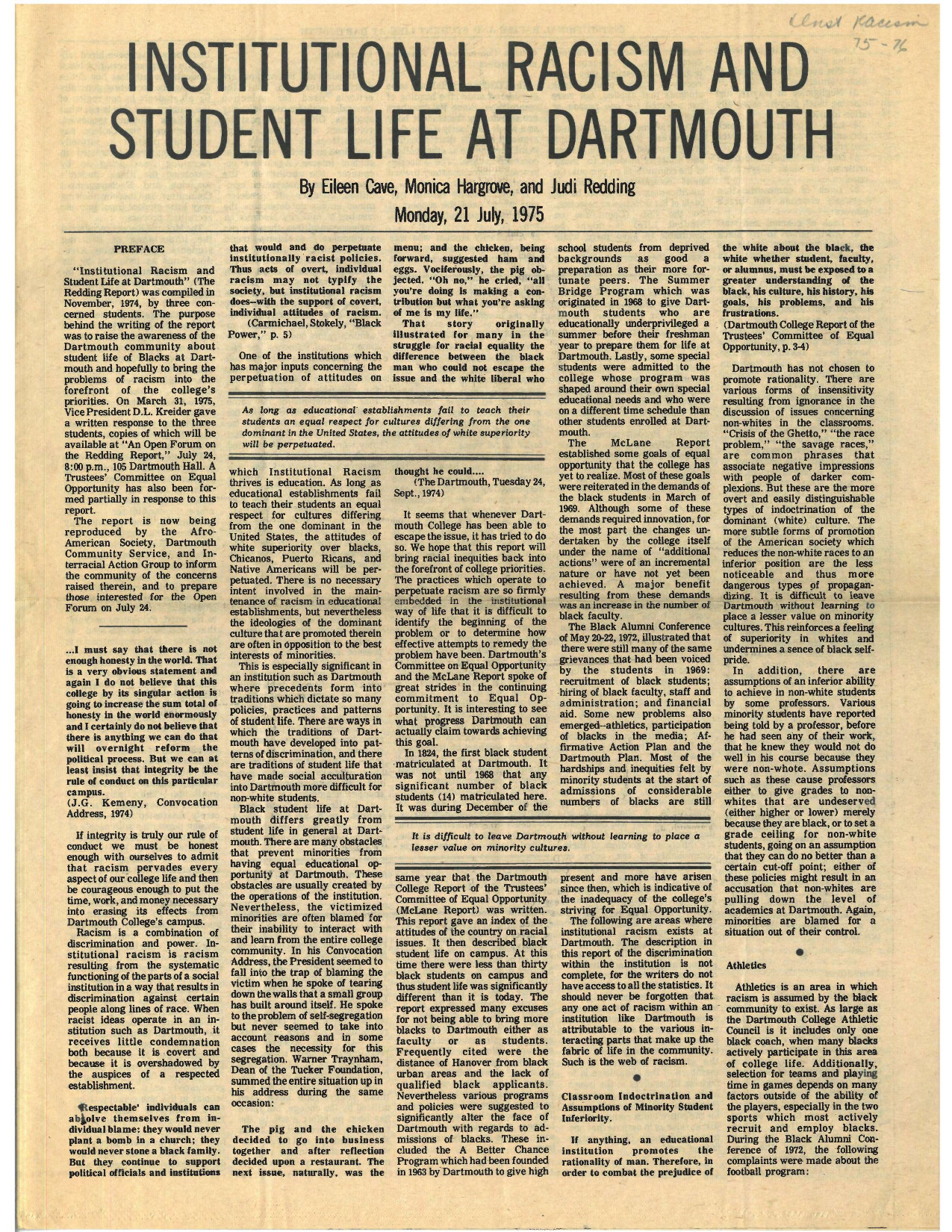

This document that Traynham refers to was likely the "Redding Report," formally published November 1974 as “Institutional Racism and Student Life at Dartmouth” by Eileen Cave, Monica Hargrove, and Judi Redding. The report was then republished as a newspaper article in July 1975. According to Redding, who has also been interviewed as part of this oral history project in October 2021, the three students came together after she had taken a course at Dartmouth on institutional racism.

“Once I took the class, I came back with the key points and we just started talking about, 'Well, that seems to be present.' And for me, institutional racism, not racism as a personal animosity, but racism in terms of the structures and the full systemic problem within an institution, that concept was new to me. So obviously we were in a particular institution, there was a dearth of people of color, there were issues with Native Americans. There were tiny in number, very, very, very few Native Americans at a time for an institution that was founded to educate Native Americans. And so we just thought, well, let's look at the numbers, let's look at positions, let's look at seniority, let's look at that across the college framework and see what happens.”—JB Redding, 2021

While Traynham viewed the committee and the institutional response to the complaints listed in the "Redding Report" from the side of the institution, as unremarkable, Redding spoke of feeling animosity from the institution. “I think they did not want a direct focus on race at Dartmouth. It was not apathy, it was animosity.” Indeed, “someone administrative came, sat an appointment with me […] and that person made a verbal, direct threat that I, as a young innocent person, it nearly broke my spirit.”

Towards a New Era: Connecting to the Student Body via Broadsides

Outside of listening to student perspectives on the Committee of Equal Opportunity, protesting outside Kemeny’s office, and standing up to McLaughlin, Traynham also published a series of broadsides, which he would send to all students and faculty. The broadsides served in place of regular chapel, but instead of preaching only on religious teachings, he would highlight certain moral and social issues that impacted the lives of students of marginalized identities.

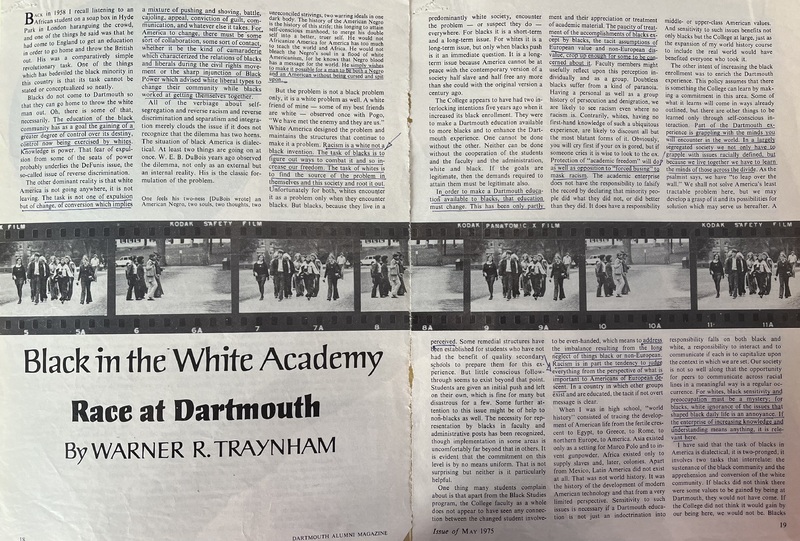

One of Traynham’s broadsides, namely “Black in the White Academy: Race at Dartmouth” highlighted the issues that likely came up during the committee hearings. Similar to the "Redding Report," it underscored many of the institutional issues at Dartmouth, but in a more generalized manner.

In at least one other instance, Traynham’s broadsides and his position on the Committee on Equal Opportunity set him up to display unprecendented administrative support for another community on campus, namely the LGBTQ+ community. In our conversation, Traynham recounted one experience where a student came up to him as chair of the equal opportunity committee to discuss the struggles that gay students were experiencing on campus. “Well, this was a surprise to me because he was the first person to mention it, and I'd been at Dartmouth, I guess, about two or three years at that point,” Traynham reflected. After this encounter, the Tucker Foundation became a sort of home base for gay students beginning in the late 70s. At this time, the students had not yet been able to receive official recognition for their organization, Gay Student Support Group (GSSG), which became the Gay Students Association in 1978. According to Traynham, the Tucker Foundation not only housed GSSG but also provided them with some funding.

Aside from provide gay students a space on campus, Traynham also made his thoughts on homosexuality public through one of his broadsides, titled “Sexuality and Homosexuality: Some thoughts.” In his Rauner blogpost about Traynham's unprecedented support for gay students in the late 70s, Val Warner '21 summarizes the broadside very well. He says that it "makes a thorough, four-page case that gay people should not be condemned on a religious, legal, or scientific basis. Traynham points out that 'condemnation of male homosexuality and the subordination of women go hand in hand in patriarchal societies,' and that '[t]here is no clear evidence that there is anything about a sexual orientation toward a person of the same gender that impedes the healthy development of an individual or endangers society.' He concludes that 'for those who know they are gay and accept it, no apologies are necessary.' This sentiment was an incredible display of support for the time, and even more meaningful coming from a religious leader."

“Of all the essays which I wrote, the one on homosexuality was the one that made the most impact on campus, and I think whenever anybody remembers them—I have no idea how many there are in the world, who do remember them—that's the one they remember. People stop me on the street to thank me for writing that. I legitimized the discussion of homosexuality on Dartmouth’s campus because there had been no discussion before.”—Rev. Warner Traynham, 2022