A Family Tradition: Life at Dartmouth

Though the first Wilson to attend Dartmouth, Ben was far from the last. Following in his footsteps, Ben's three younger brothers Harrison, '77, John, '80, and Richard, '85, all attended the rapidly evolving College on the Hill.

"Dartmouth looked like what a college was supposed to look like": Cultivating Diversity in the White Mountains

Ben entered Dartmouth at a pivotal point in its cultivation of Black student life. During the interview, Ben pointed that he entered in the first class where about ten percent of the student body was Black. Dartmouth had accepted 130 of the year’s 230 Black applicants – nearly dwarfing the total number, 150, of Black men who had graduated from the school over its 200-year existence. This change was drastic and headline-making: see the attached clipping from a New York Times article about the Class of 1973 published in 1969.

As the article explained, this shift stemmed not from institutional initiative, but the work of recent alumni who sought a better future for their successors. The school had previously made claims that despite their willingness to enroll Black students, there simply “just [weren’t] enough qualified” to enroll and succeed at the institution. In response, early founders of the AAM requested funding to find them. Using a five million dollar-grant distributed over a five-year period, students traveled to “every large city in the country”, visiting high schools and “hangouts” to speak to prospective students as peers. Remarked the dean of the financing endowment, “they spoke to these kids as brothers, and that’s something we could have never done”. This drive was successful – and the results were not only the most diverse class in Dartmouth’s history at the time, but the expansion of financial aid programs, the creation of remedial writing and mathematics classes, and “Bridge”, an early predecessor to the First Year Student Enrichment Program, a summer intensive program which brought Black students to campus to take regular college courses for full credit in a more individualized environment.

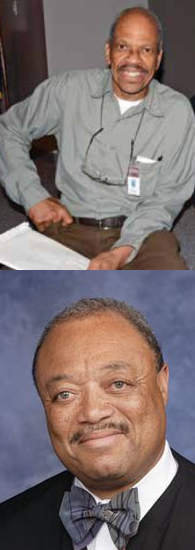

Many of Ben’s classmates were galvanizing forces behind this recruitment, formalized as the Black Student Application Encouragement Committee, including teammate Bill McCurine and predecessor Ronald Talley. Talley was interviewed for the Dartmouth Black Lives Oral History Project in 2021, and his interview can be accessed here. A ‘69 from Anderson, South Carolina, Talley studied sociology and was heavily involved in recruitment, later serving as the director of a field program in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Talley also worked as a resident tutor for the A Better Chance program during his junior year in Andover, MA and returned to campus post-graduation to work in the Office of Institutional Research and Counseling and teach a course on community development and organization in what would become the Black Studies department. Remarked Talley of the initiative,

“I think it was especially valuable because even to this day… I still see the shortcomings of well-meant efforts where students… set out to have an impact on a needy population, but nowhere within their ranks do they really have expertise as to what's going on the ground… What that project did for those of us who were concerned about long-term solutions… was it helped us realize.. that whatever we sought to do we were going to have to first establish relationships with target populations and embed ourselves there. And, if not embed ourselves there, then in establishing that relationship… let them tell us what we should be doing. Not us go in there as the Ivy League experts and tell them what they should be doing."

Rhodes Scholar and former teammate Bill McCurine also spoke extensively during his interview of his involvement with A Better Chance and other recruiting programs. For Bill, ABC functioned as an “activist arm” through which he was able to both accrue more Black students and a heightened sense of political awareness. A native of Chicago, McCurine also provided valuable insight into perhaps the school's most controversial effort, the Foundation Years program. The brainchild of Associate Dean Dey, the progam sought to recruit and educate youth directly from neighborhoods with gang activity. The effort first focused on the Vice Lords, a gang spawned from incarcerated youth in Chicago, Illinois whose numbers now reach an estimated 30,000. Noted for its proclivity for violence, many of its members were encouraged to ascend its ranks without completing high school or pursuing higher education. Building off the legacies of DeWitt Beall, ‘65, and David Dawley, ‘63, both of whom worked closely with low-income neighborhoods in Chicago upon graduation, Dey promised to admit gang members with the caveat that money be raised externally to fund two scholarships. With the help of Ken Montgomery, ‘25, the school soon had enough money to fund four. Dey enlisted McCurine and other members of the AAM (including Woody Lee, ‘69), to meet and advise members of the gang through matriculation. Remarked Bill of meeting and befriending these students,

“Well, they were all dressed to the nines. They just blew us away because this is not what we thought they would look like. They were all at least four years older than the rest of us… They were really such interesting people. All of them finished Dartmouth. All of them went on to have some kind of a career. I'm still in touch with Crump. Still in touch with Alan. I don't call him Tiny anymore, I call him Alan. Henry Jordan died about four years ago. Two to four years ago. Oh, they were they were amazing people. They were leaders.

In total, Dartmouth would matriculate fifteen students through the Foundation Years program, the last of which graduated in 1973. For an extensive profile of the alumni and roots of the Foundations program, access this article from Chicago Mag.

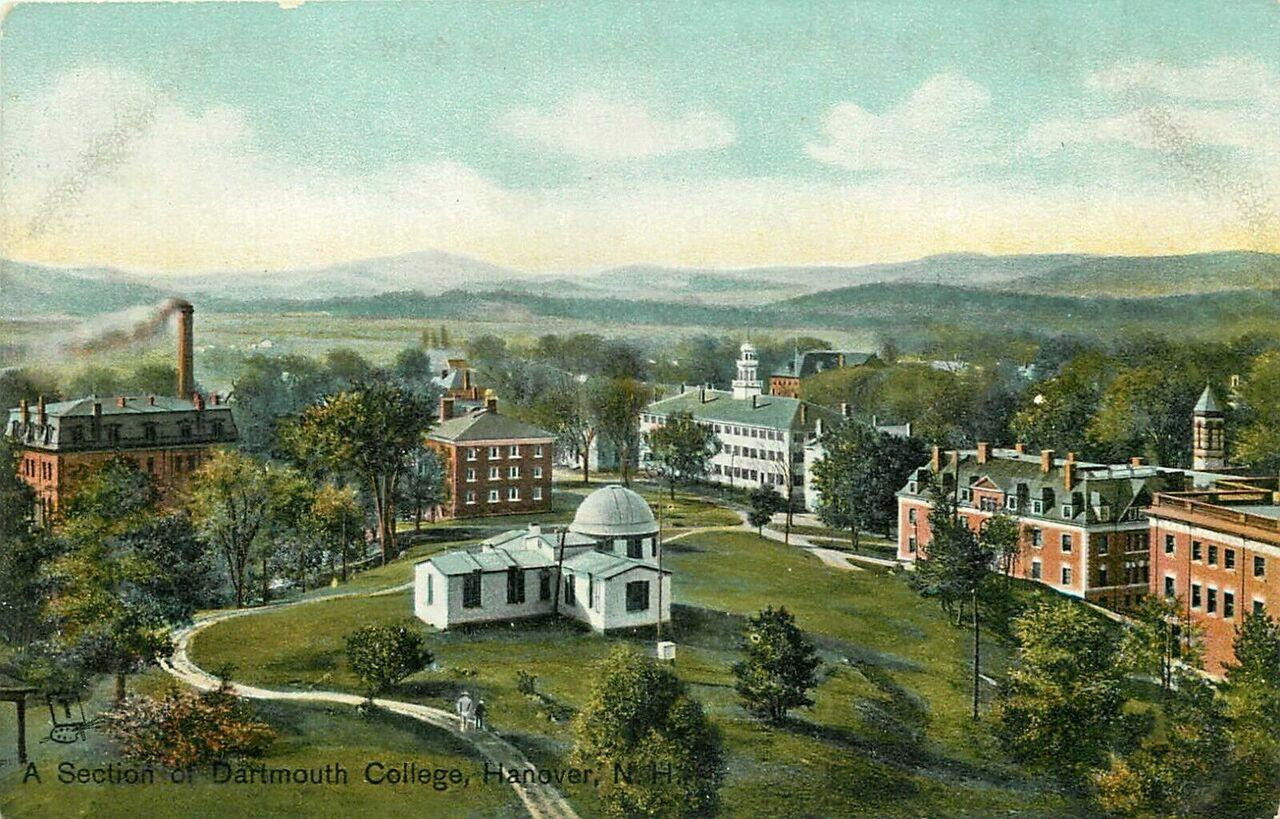

While Wilbraham did not have a partnership with A Better Chance, he listed it among the numerous influences that encouraged him to apply to and attend Dartmouth. Many of the reasons listed for his decision are surprisingly simple–including among them an appreciation of nature, time away from the city, and the tight-knit community. In Ben’s own words:

“It was rural, and that attracted me. I felt like I was going to spend most of the rest of my life in the city. So I thought it would be nice to be near the Connecticut River, to be near the Green Mountains and the White Mountains… Dartmouth looked like what a college was supposed to look like from a Currier and Ives postcard.

And I mentioned there were several students who’d been in the ABC program and they spoke so highly, not just of Dartmouth, but these upperclassmen who had encouraged them. And, and so I said, “I'd like to be in a place where there's that type of positive reinforcement.” And it turned out it was really true, when I got here, they were like that."

"It confirmed for me that there were possibilities": The Early Days of the AAM

While Ben was not intimately involved with the AAM during his time at Dartmouth, he speaks highly of the tight-knit community that formed around him. Ben spoke most particularly about Dartmouth being a valuable conduit of forming connections with those who would serve as mentors–from upperclassmen to prominent guest speakers. Remarked Ben on the AAM,

“For me, it was a cultural affirmation. It was an opportunity to learn from students who were older. We had amazing speakers come to campus. W.E.B. Du Bois came to campus — Julia Bond… Percy Julian… and I got to meet these people. And, it confirmed for me that there were possibilities for me, they were human, just like me. But what I would also say was that there were other Black students at Dartmouth who were excelling academically, Bill McCurine [‘69], Jesse Spikes [‘72], Willie Bogen [‘71], my teammates on the football team, were Rhodes Scholars. I had four other Black classmates who were at Harvard Law School with me… And so, you know I wanted to excel, and, and there were a lot of positive examples of students ahead of me at Dartmouth, and my peers in my class. And then I had again, professors who were encouraging, Jim Wright was one of those. And I had great admiration for him.”

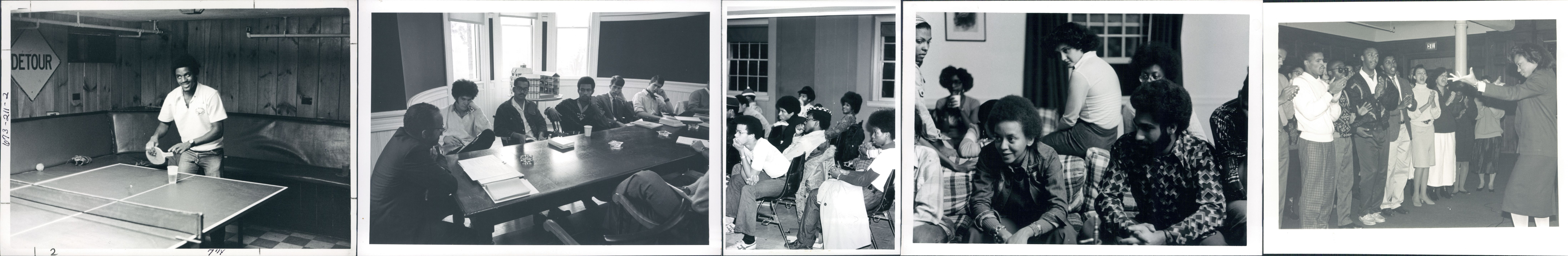

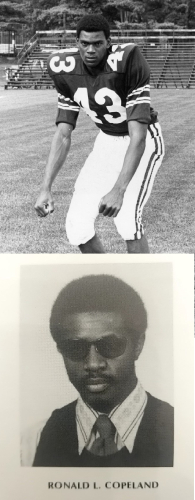

For many students, the AAM also provided a place of solace and companionship otherwise rare on a cold, predominantly-white campus. Not yet accepted into most fraternities and without a city to escape to, students of the AAM would often host informal and formal gatherings in Cutter-Shabazz or invite students (often women) from neighboring schools for socials. Affiliation differed by student, especially as a diversifying student body sought increasingly to infiltrate historically white institutions. Below are remarks on the AAM from previously interviewed Black alumni, including teammates Ronald Talley ‘69 (a Tabard and founding member of the AAM), Willie Bogan ‘71 (who was affiliated with a fraternity), Bill McCurine ‘71 (Vice President of Blackout magazine and a founder of the AAM), and Ronald Copeland ‘73 (who would serve as President of the AAM).

WILSON: “Well, I met a lot of students, and I was friendly with everyone when I got to Dartmouth. And—so I think it's because I was known by others. That's probably why I was elected the vice president… Listen, for me, my most fun at the AAM were the parties. Right? And my practice was to study until 10:00, 10:30, 11:00. The party didn’t get started until late. And then, you know, once I knew I had my work done, if this party was Friday or Saturday. Then I felt like I could enjoy myself. But yeah, you know, for me it was social opportunity. So when we had parties, and there were women on campus… that's generally, when the parties took place.”

TALLEY: “I was a member of Tabard and Tabard was a very liberal, open organization… What I did is I ended up living kind of a dual life, which I had done much of my life anyway. My time at Tabard was I would have to define it as social time. It was a place to go for football weekends, home games and everything else. It was a place to watch television and hang out. And then I had my, what I would consider my work and serious life, with mostly Black students and the Afro-American Society and everything else. I managed those well.

BOGAN: “The Afro-American Society, that provided us a forum for talking about what was going on and talking about ways in which we could have some impact, then and in the future. And so it was very purposeful the, I would say that the first and foremost purpose of the Afro-American Society was again: survival at Dartmouth. Survival at Dartmouth meaning making sure that everybody who was there graduated and did well. So that was it, it was that first and foremost. And then it was a support group to allow folks to air frustrations and thoughts about things that were going on. And to formulate, how can we, during our years there, have some impact on the outside world, as we called it… But, more fundamentally, it was a social group. It was where we would go and we would hang out. We would just have a good time with one another. It was a support group for the blacks on campus: It was, sometimes we felt isolated, as a group and, and so it was a way of dealing with that isolation.”

MCCURINE: “Well, oh, one we didn't relate to the fraternity culture and a lot of the fraternities were racially segregated. They didn't want blacks and we were young, proud black men, they didn't want us and we didn't want them… And the fraternity culture with, you know, beers, and white girls and listening to The Beatles. That was just, even if you wanted to do that you would never admit it. [The AAM] was really the center of our social and political lives. We would host parties and have black women from other schools come up, or we would travel together to road trips, where other black student groups are having social gatherings. It was as important as fraternities are to its members.”

COPELAND: “When I got more familiar with the work of the Afro-American Society and got active in that and started to spend more time with that work and the leaders of the group, and some of the social activities engagements with that — and… was asked to serve as a president — that's where my extra time went... This was just a continuation of the stream of activism, for me… It was a broader brain trust of folks that were saying that if we're going to now — because what Dartmouth, at least the leaders at that time we're interested in is, this is not going to be just a temporary thing with increasing Black presence both in faculty and students on our campus, this is now our part of our future in who we are."

- Legacy: Benjamin Wilson ‘73 (Emilie Hong ‘25, Fall ‘22)

- An Oral History Interview with Benjamin Wilson, '73

- Long Strides: Harrison B. Wilson and HBCUs

- "My mother's spirit is speaking through them": Anna G. Wilson in Life and Death

- "I wanted to know why": History and the Deep South

- "I had a chance": A Lifetime of Learning at Wilbraham Academy

- A Family Tradition: Life at Dartmouth

- Living With Legacy: Career, Love, and Community Post-Graduation

- Bibliography