“Intruders”: Arriving at Dartmouth

Transitions

"After I got [to Dartmouth], it got interesting in a lot of different ways. The first thing that happened was I met my first roommate and then the second roommate showed up several hours later. And he was introduced to me by the first roommate. [...] He would not shake my hand and he then subsequently moved out. And we never saw him again." Ron shrugged this off. "As far as I was concerned, it was his problem, not mine."

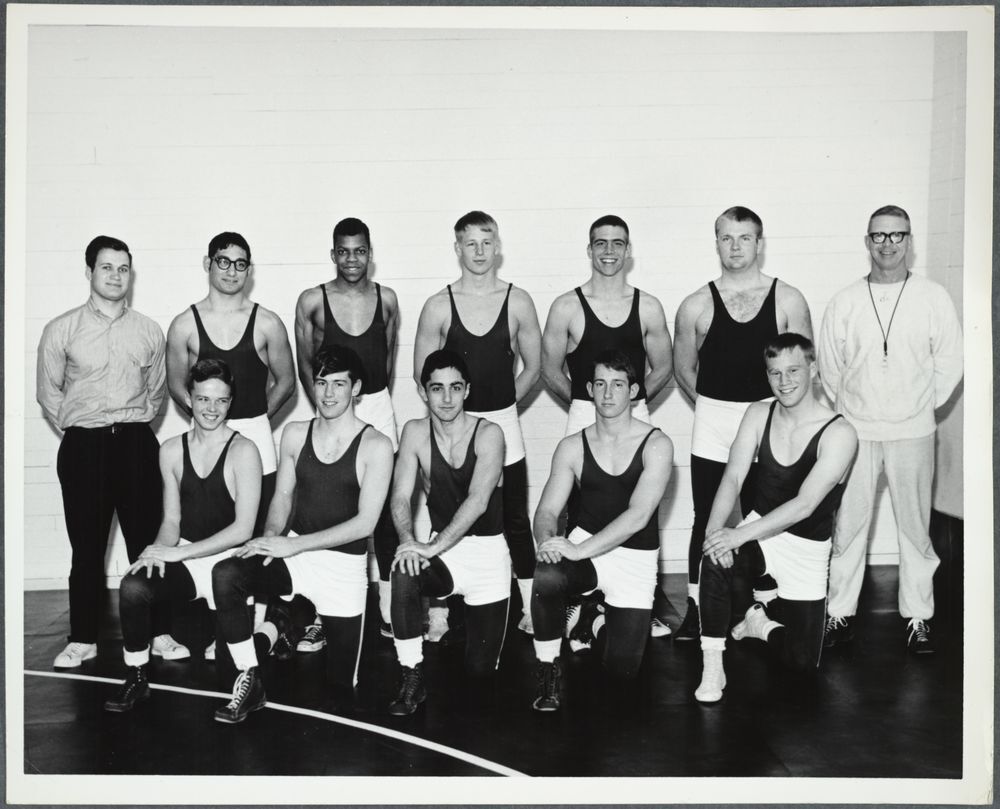

Ron remained close with his first roommate, eventually trying out for the wrestling and football teams becuase his roomate was on the teams. After a few terms he decided to quit the teams and focus on his academics. He remained friends with the people he met on the sports teams and later joined The Brotherhood of the Tabard.

"What I did is I ended up living kind of a dual life, which I had done much of my life anyway. My time at Tabard was, I would have to define it as social time. [...] And then I had my, what I would consider my work and serious life, with mostly Black students and The Afro-American Society and everything else. I managed those well."

Being Black at Dartmouth

"I think we just felt like we were in the Upper Valley. That we were just as far north of the Mason-Dixon line as if we were in the deep south."Ron Talley, on the atmosphere of racism at Dartmouth

In Stefan Bradley's book Upending the Ivory Tower, he describes Dartmouth as an institution whose policies "suggested some respect for the Black freedom struggle." Unlike many other Ivies, Dartmouth did not have a large riot or demonstration to achieve the same goals. Dartmouth had a generally more supportive and proactive administration. But because Dartmouth was so rural, students had no local Black community with which to partner. Much of the labor for improving Dartmouth fell on the backs of current students.

The attitudes of the administration did not translate to that of the student body. Ron describes seeing students flying Confederate and Nazi flags. "At that time, Dartmouth was very white, male, tradition entrenched. And so, everybody else was seen as an intruder into that club. You keep in mind that this was also a time where the school mascot was a Native American. The caricatures of Native Americans abounded on campus."

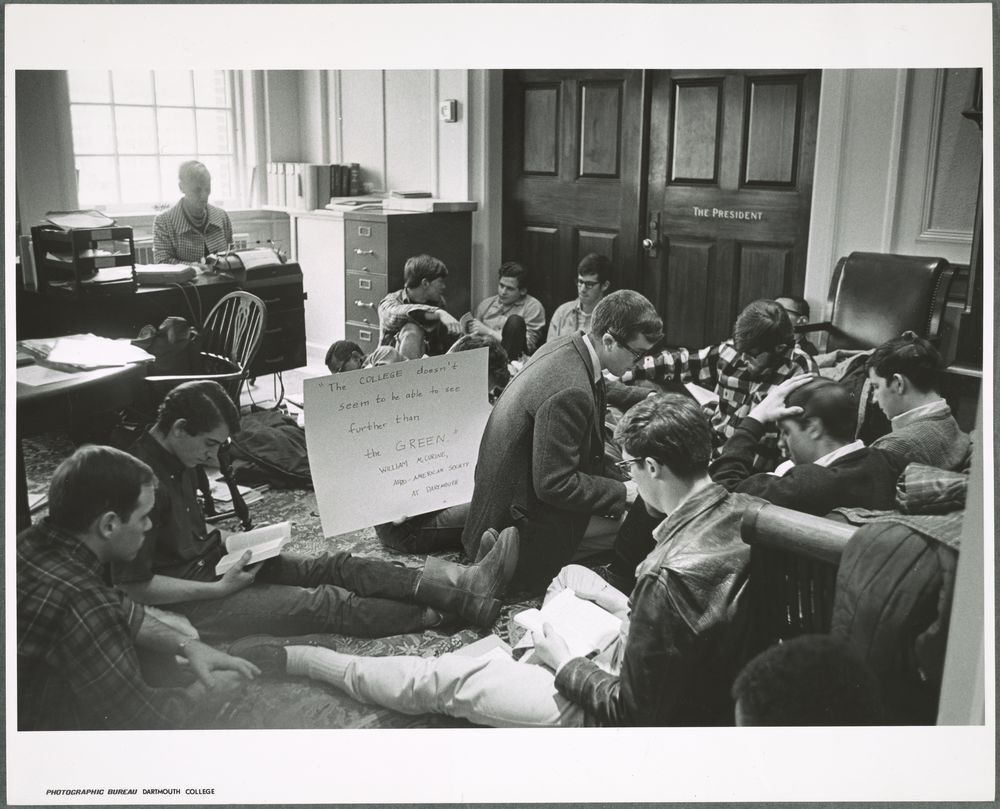

Protests

Although Dartmouth did not have major demonstrations like other Ivy League institutions, there were a few notable protests in response to the Vietnam War, Eastman Kodak (see photo), and speakers brought to campus. In Ron's time, Dartmouth invited both William Shockley, a physicist who argued for the genetic inferiority of Black people, and George Wallace, racist Alabama governor, to campus. Ron attended these protests. "It should have been the College's responsibility to present the counterpoint speakers for each of these cases, if it's going to be a true open education environment. I think what happened was, certainly to me and the rest of us, was you know: here's ol’ racist New Hampshire and Dartmouth. I think we just took the attitude that the College and most of the other students supported the Wallaces and Shockleys." In the case of the 1967 Wallace protest, the Dartmouth Administration sent an apology letter to Wallace because of the disruptions students caused, an action that shows even the relatively supportive administration of Dartmouth was sympathetic and welcoming to white supremacists.

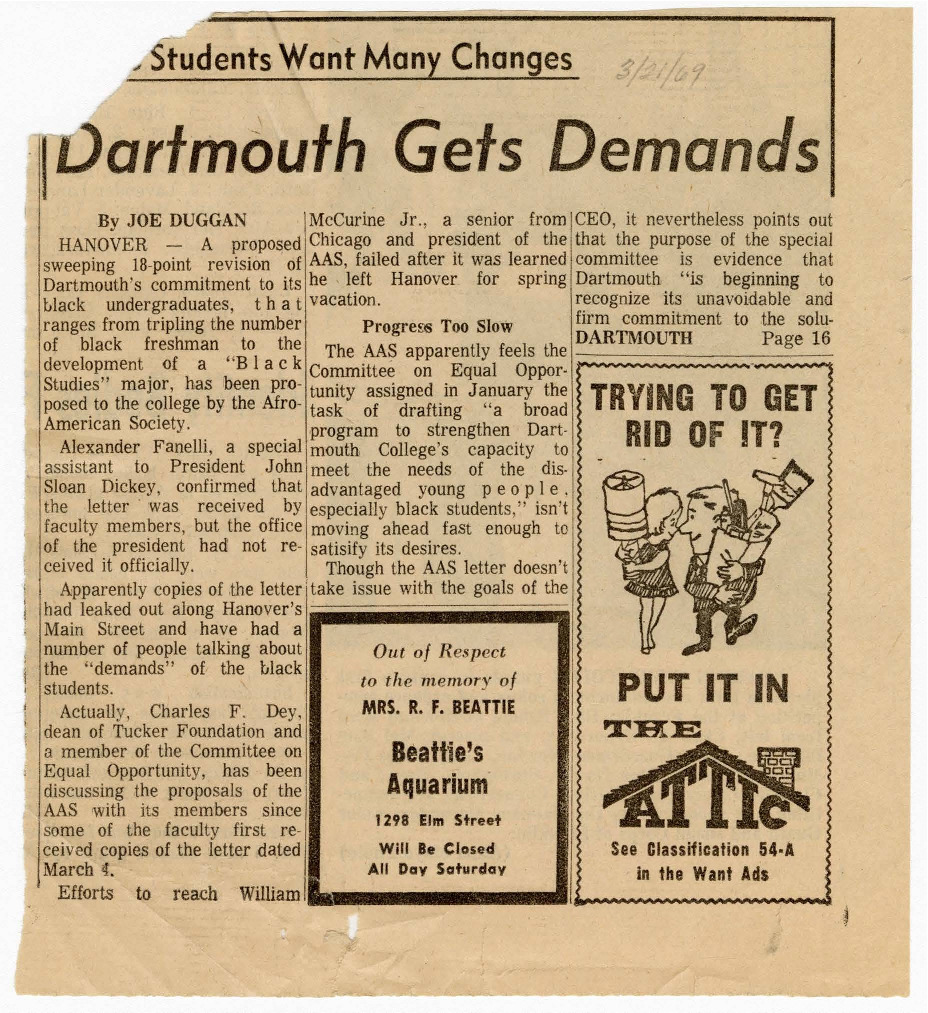

The Afro-American Society

The Afro-American Society, often refereed to by students as "The AAm," was created in 1966 and formed the center of Black life of campus. "I would say that the first and foremost purpose of the Afro-American Society was survival at Dartmouth," Ron said. "Survival at Dartmouth meaning making sure that everybody who was there graduated and did well. And then it was a support group to allow folks to air frustrations and thoughts about things that were going on. And to formulate, how can we, during our years there, have some impact on the outside world, as we called it."

As part of a list of eighteen demands, The AAm recieved Cutter Hall (later renamed El Hajj Malik El Shabazz, now The Shabazz Center for Intellectual Inquiry) as their center for education on campus. A lot of emphasis was placed on academic support, and Cutter-Shabazz had libraries and hosted guest speakers. Students set up tutoring and advising groups for each other that the College did not offer them. "It was always assumed that the student had a support structure, typically your parents. And many parents were Dartmouth alumni." Once Ron graduated, he was hired as a counselor and passed on the knowledge he had accumulated to new undergraduates.

The AAm was also very important as an activist organization on campus and did much of the legwork to make Dartmouth a welcoming place for new Black students, as we can see from their projects discussed on the next page.