Dartmouth Black Activism

Black student movements in the US arose from movements in the Black community. Different leaders, such as Malcom X and Martin Luther King, Jr., and organizations, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, (SCLC) influenced the direction of Black student movements. Black student movements reached a peak in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Many students have experienced a social awakening and a transformation of racial consciousness during their four years of college. For Thibodeaux, he had to acknowledge his "baggage." He attributes much of his ability to confront his baggage to the African and African Americans Studies program at Dartmouth and the Afro-American Society.

"Everyone has biases. Some subconscious and some unconscious biases that you've got to go to deal with. I went on campus believing what I've been told, all my life... I came to campus not knowing a hell of a lot about white society. I learned about white society. I thought that all white people were racist and that they really didn't care about social justice, they only cared about advancing themselves."

Thibodeaux '71

For many Black students, college was the first time they were surrounded by, met, and interacted with white people. Black students faced various forms of discrimination such as classroom prejudice, exclusion from clubs and organizations, microaggressions, and explicit racism.

The death of Martin Luther King, Jr. served as a wake up call for many college students. It was time for them to exit their college bubble and remember the fight for racial equality taking place across the nation. Richard Benson in his book Fighting for Our Place in the Sun, described the effect of King's assassination as a

“decisive turning point in the call for more autonomous representation by Black students nationwide. The nationwide protests that occurred in almost every major city, coupled with the presence of Black students, raised levels of consciousness in predominantly white campuses and created a new set of dynamics for college administration”.

Benson

Although Dartmouth avoided the kind of dramatic and violent demonstrations that its peer institutions had seen, their smaller-scale Black student actions were impactful and unforgettable. Black student activism led to changes and implementation of new programs to attract, maintain and protect Black students.

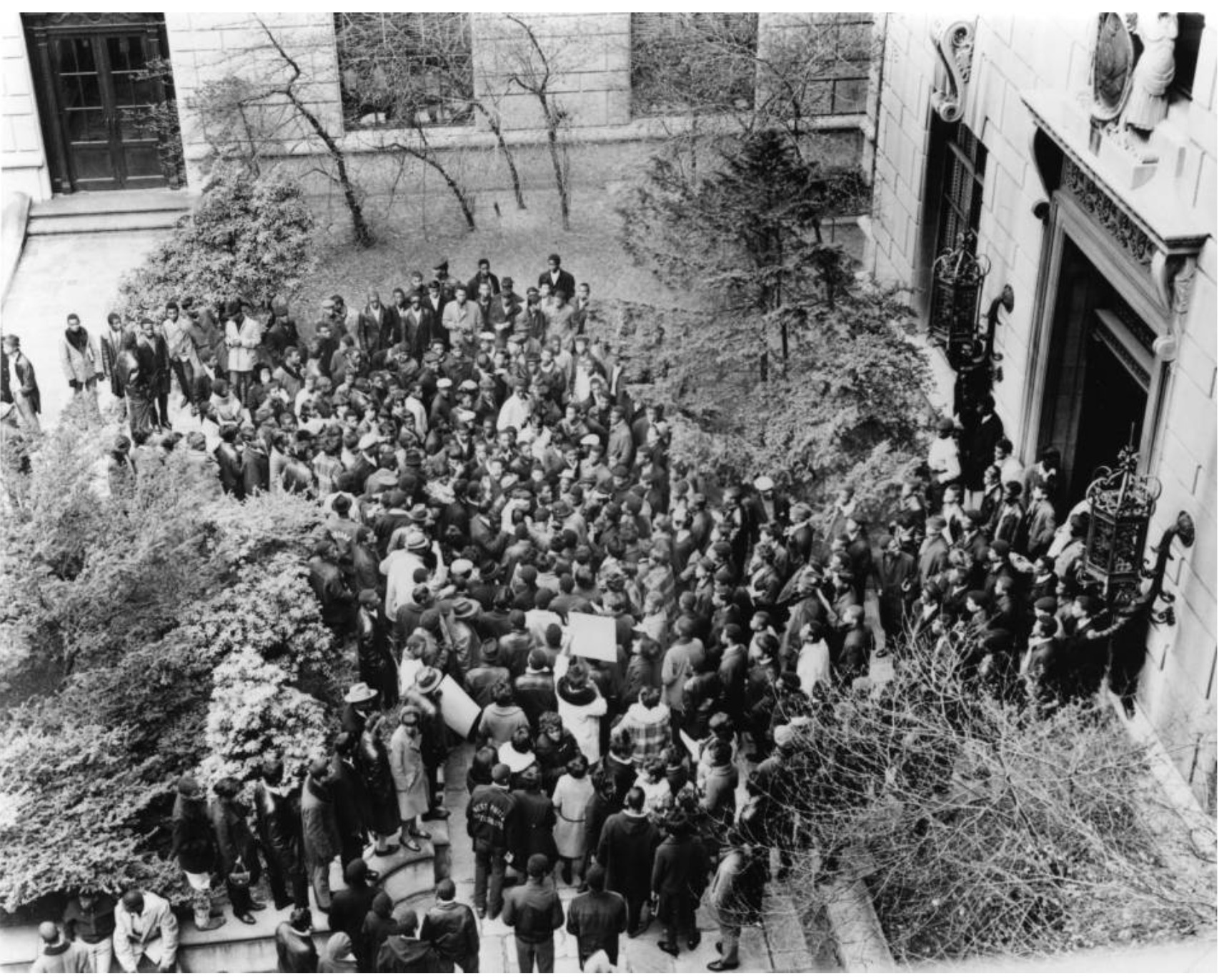

The explosion of Black Student activism in 1968 took many by surprise and the impact of its conflicts, negotiations, and reforms are currently seen on many college campuses. As described in Black Revolution on Campus by Martha Biondi, "Black students organized protests on nearly two hundred college campuses across the United States in 1968 and 1969, and continued to a lesser extent into the early 1970s." In The Campus Color Line, Eddie Cole notes that student demonstrations were the most visible challenge the Black Freedom Movement presented to college presidents.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Black students led the movement against Jim Crow segregation like those who came before them. Black students wanted access to higher education, and they wanted that education to include the fight for racial justice. The Black Student movement of the 1960s started with sit-ins. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was integral in leading direct action against racial discrimination. Stefan Bradley states that “due to the activity of the new generation of students, Dartmouth officials made policy changes regarding college life and the curriculum.” Black students were creating change locally and nationally.

On November 17, 1967 over seven thousand Black students demonstrated at the board of education in Philadelphia to make their demands. This demonstration was the turning point for the Black student community as the slogan "Black Power" emerged and, as Dr. Bradley calls it, "Black Student Power" became evident. By 1968, the Black Studies rebellion had spread nationwide. Protests arose at white institutions when the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front argued with San Francisco State administration over Black Studies.

Many Black students attending Predominantly White Institutions (PWI) such as the Ivy Leagues during the 1960s and early 1970 were expected to act 'white' and assimilate to the "All-American culture." However, black students resented the pressure to assimilate, the lack of acceptance, and the racism they had to endure. As a result, Black student activism exploded as the right for racial equality was brought to college campuses. An example of Black protest at Dartmouth was the protest against Alabama governor and segregationist, George Wallace.

Dartmouth hosted figures such as Alabama Governor George Wallace and racial theorist William Shockley, creating student uproar. By 1967, the approaches to the Black Freedom Movement shifted from boycotts and sit-ins to militant tactics.

When Wallace, whose mantra was "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever," visited Dartmouth for the second time; students met him with militant strategies compared to the silent civil disobedience protest he encountered on his first visit several years earlier.

Shockley, propagating eugenics, claimed that Blacks were the less intelligent race and were reproducing quickly, weakening American civilization. Gene spoke of how Shockley was unable to give his speech because the students "did not allow him to speak on campus." Every time he attempted to read his speech, students would clap loudly, interrupting and drowning out his voice.

In clapping, students violated one of Dartmouth principle; the right to liberal education. Members of Dartmouth’s Black Judicial Advisory Committee (JAC) recommend that no penalty be given against the seventeen Black students who participated in the clapping demonstration during the Shockley presentation. The committee members called for Dartmouth to clarify its rules governing campus behavior, as the student demonstrators acted in self-defense.

Thibodeaux participated in student activism; however, like many black students, he had to decide if the potential consequence of activism was worth the cause. He explained that he did not join the student takeover of Parkhurst during the Vietnam war protest because one, he "was not going to risk expulsion"; two, the protest did not "contribute anything for the advancement of black students on campus," and three, it did not do anything to foster his personal growth. Thibodeaux describes his decision to not participate as

"my father was not an officer of General Motors, he was not a CEO of a major fortune 500 company, and so I'm not about to risk... my educational future on that sort of thing particularly when I did not see much coming out of that."

Thibodeaux '71

After graduating, Thibodeaux worked one year as the Dean's assistant. "I felt that I could be a mentor to other incoming students, and that's why I took the job as an assistant to the dean because I felt that I could lessen some of the barriers, some of the hurdles that I knew I had to go through," he explained.

As a student, he joined the Afro-American Society and helped recruit black students to Dartmouth College. In the 1960s, the Afro-American Society initiated what is now known as the Black Student Application Encouragement Committee (BSAEC). The program was founded with the intent of sending Dartmouth students to recruit Black students from their hometowns during their breaks and vacations. Their efforts were successful, as more Black students applied to and were accepted by Dartmouth.

Previous: Gene Thibodeaux Interview -- Next: Conceding to Students Demands