Home Away From Home: Trials and Tribulations

Black Brotherhood in the Woods

"I grew up an only child, so the brothers I went to school with were my brothers."

- Wallace Ford '70

Upon his arrival to Dartmouth, Mr. Ford describes meeting the second largest cohort of Black students on campus at the time. A critical mass, there were enough students to demand the college make institutional changes. With a belief that he would change every place he went to, school or work, he was determined to make Dartmouth different. In all his schooling, there had never been more than two or three black students in any of his classes. Coming to Dartmouth, he became intellectually and socially involved with a brotherhood of approximately sixty Black undergraduate men who engaged with texts ranging from Frantz Fanon to James Baldwin. Embraced by the upperclassmen, they taught him the importance of advocating and taking advantage of the opportunities afforded to him. Forming fraternity among each other, they made their voices heard and challenged administration to meet their demands.

The Cost of an Elite Education: The George Wallace Event

Known as the most conservative Ivy, Dartmouth hosted notorious social and political figures. In 1967, George Wallace, Governor of Alabama at the time, made his second visit to campus. An avid segregationist who encouraged police brutality and racist agendas, Wallace used his political power to maintain control and force over Black communities. Having visited the college once before in 1963, his administration did nothing as four girls in Birmingham were brutally murdered in a church bombing. Instead of supporting racial integration, he deployed police force on peaceful protesters in the Children's Crusade and blocked students from entering into university. With the belief that Dartmouth students "were better representatives of an educational institution than those at Harvard" (Bradley 147), who prevented him from speaking, Wallace had the false perception that the campus he encountered four years earlier still held the same values and sentiments.

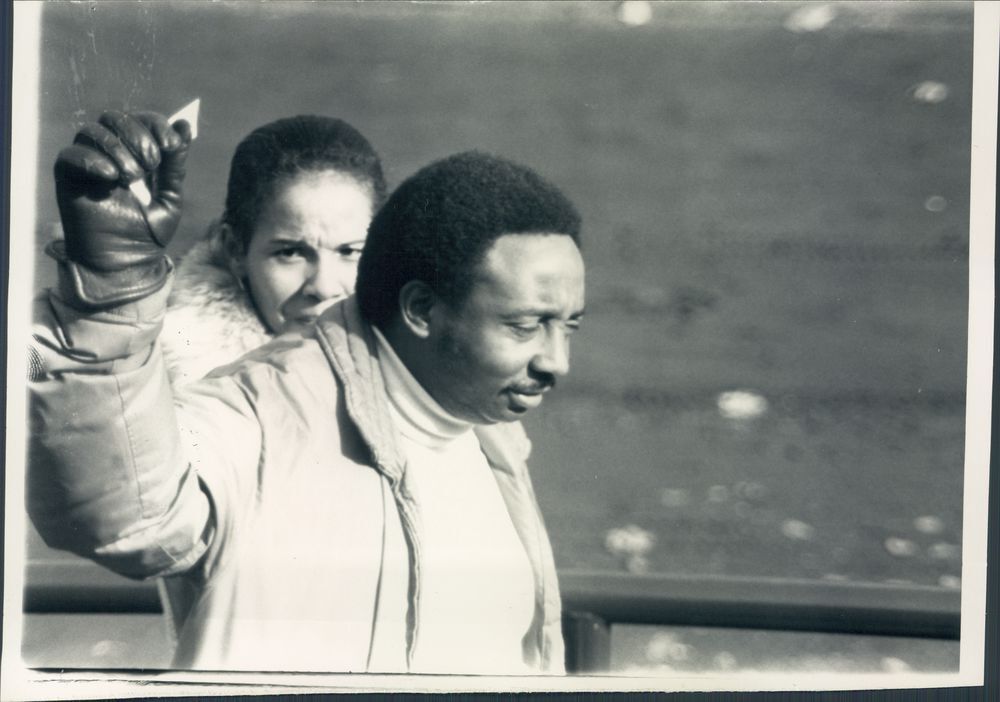

Arriving at Dartmouth for a second time, the governor found that students and faculty employed more militant actions. The Afro-American Society, of which Wallace Ford was a member, held up signs in protest of George Wallace's entrance. Making too much noise for the governor's liking, he decided to leave. As George Wallace got into his car, students surrounded his vehicle and rocked it back and forth repeatedly. Ford recalls that "you [could] see the wheels coming off [and] the tires coming off the pavement" and the stern look on the governor's face (interview transcription). Receiving national media attention on CBS Sunday Night News, Dartmouth alumni had their own response to the events that took place.

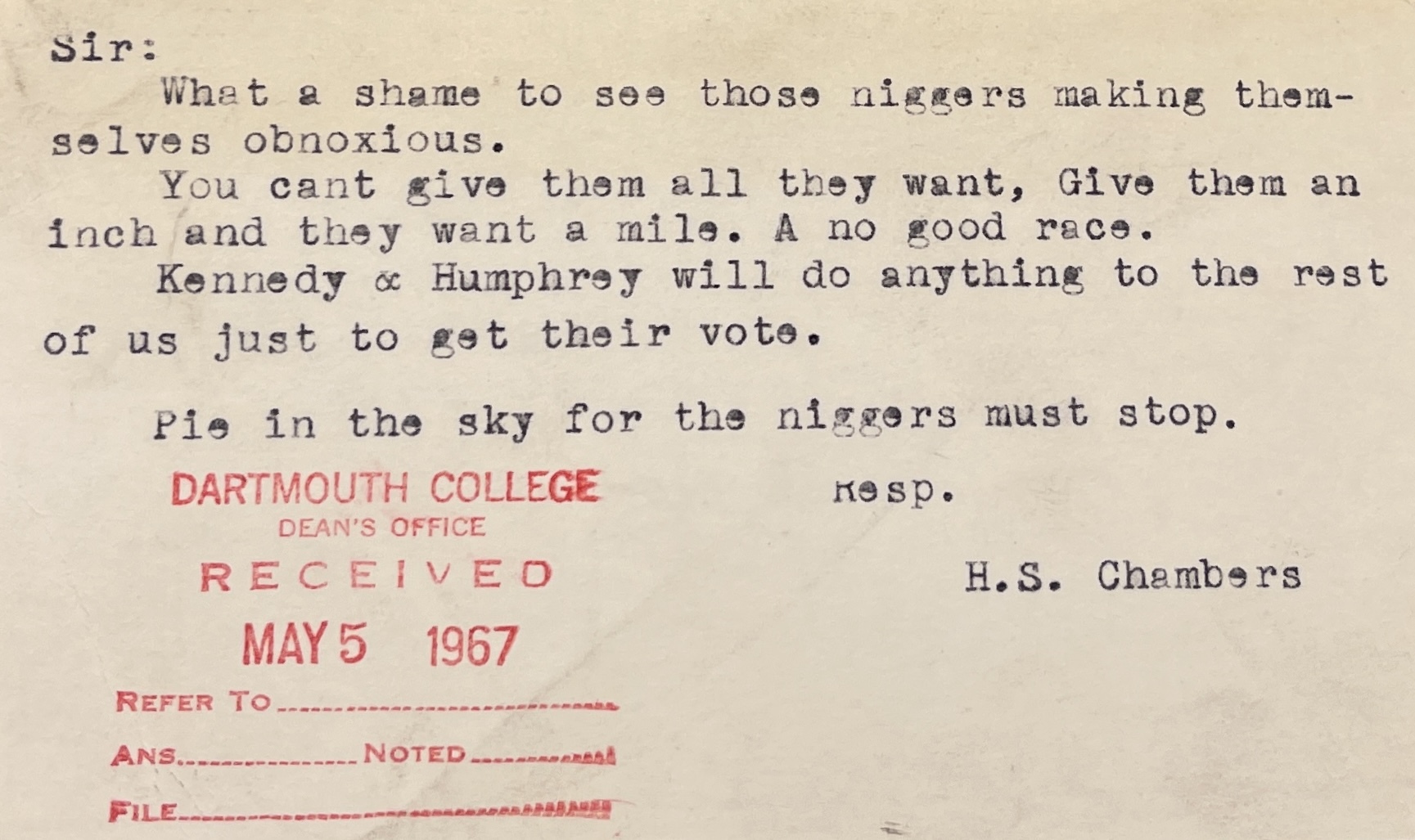

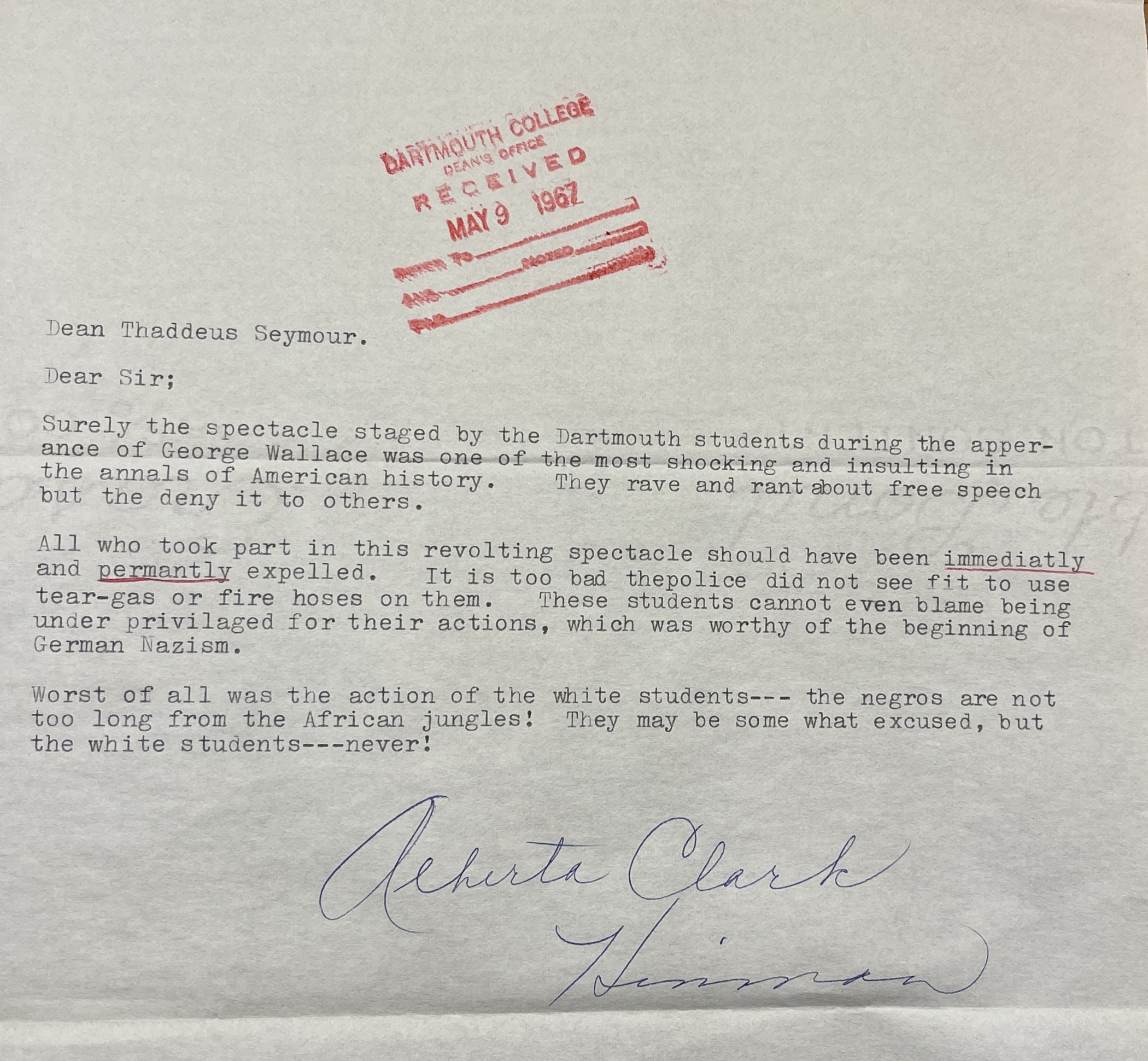

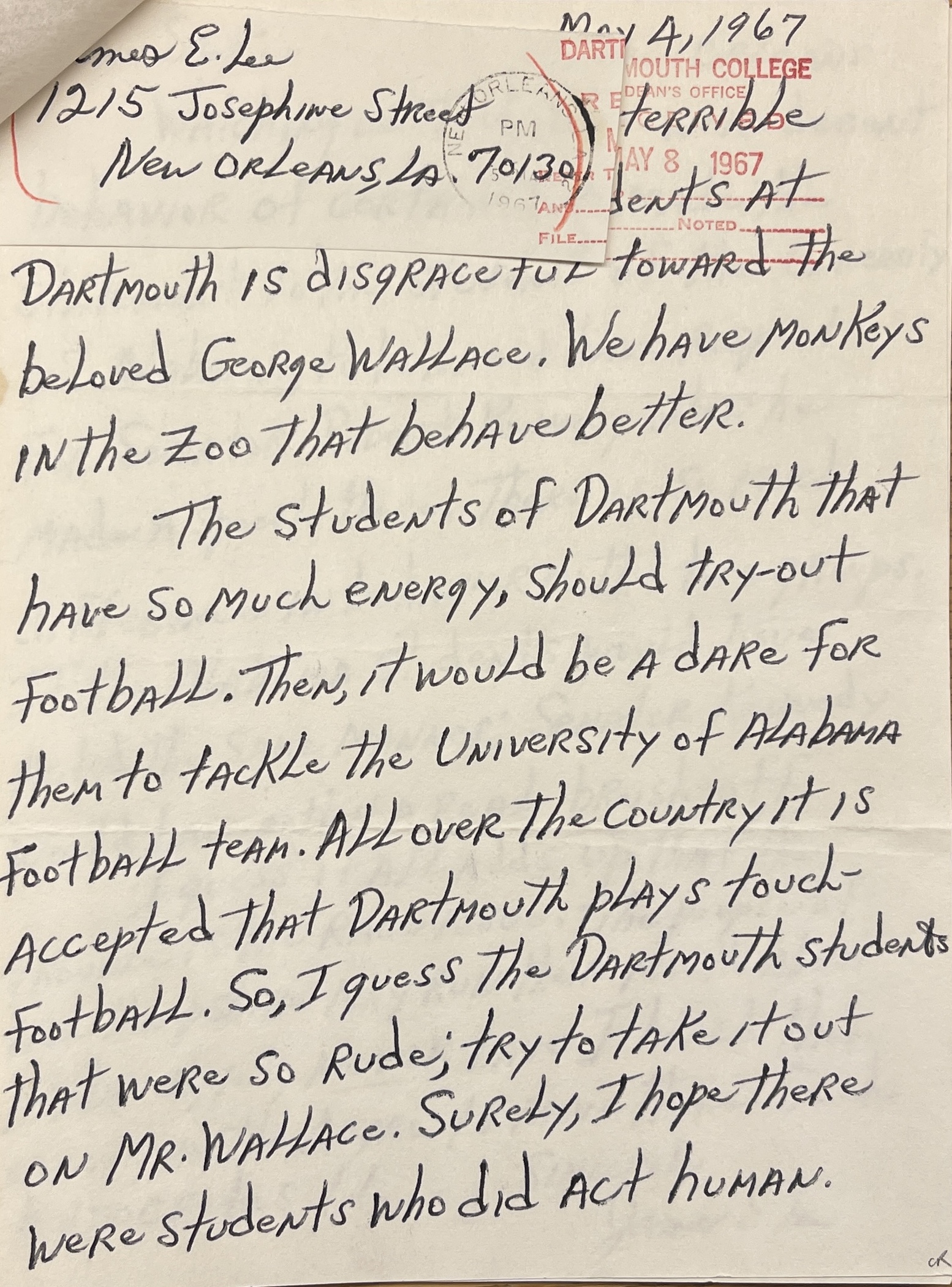

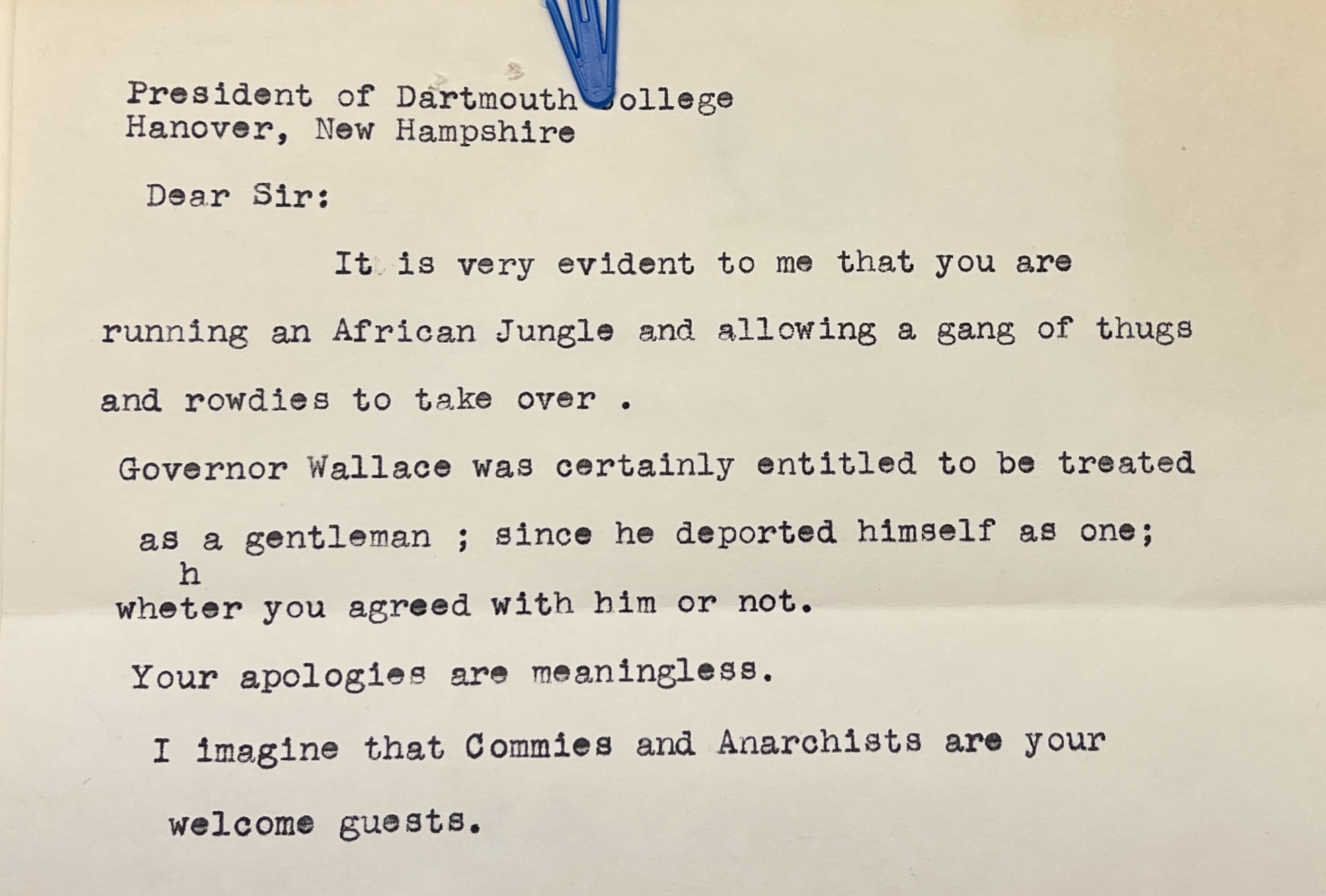

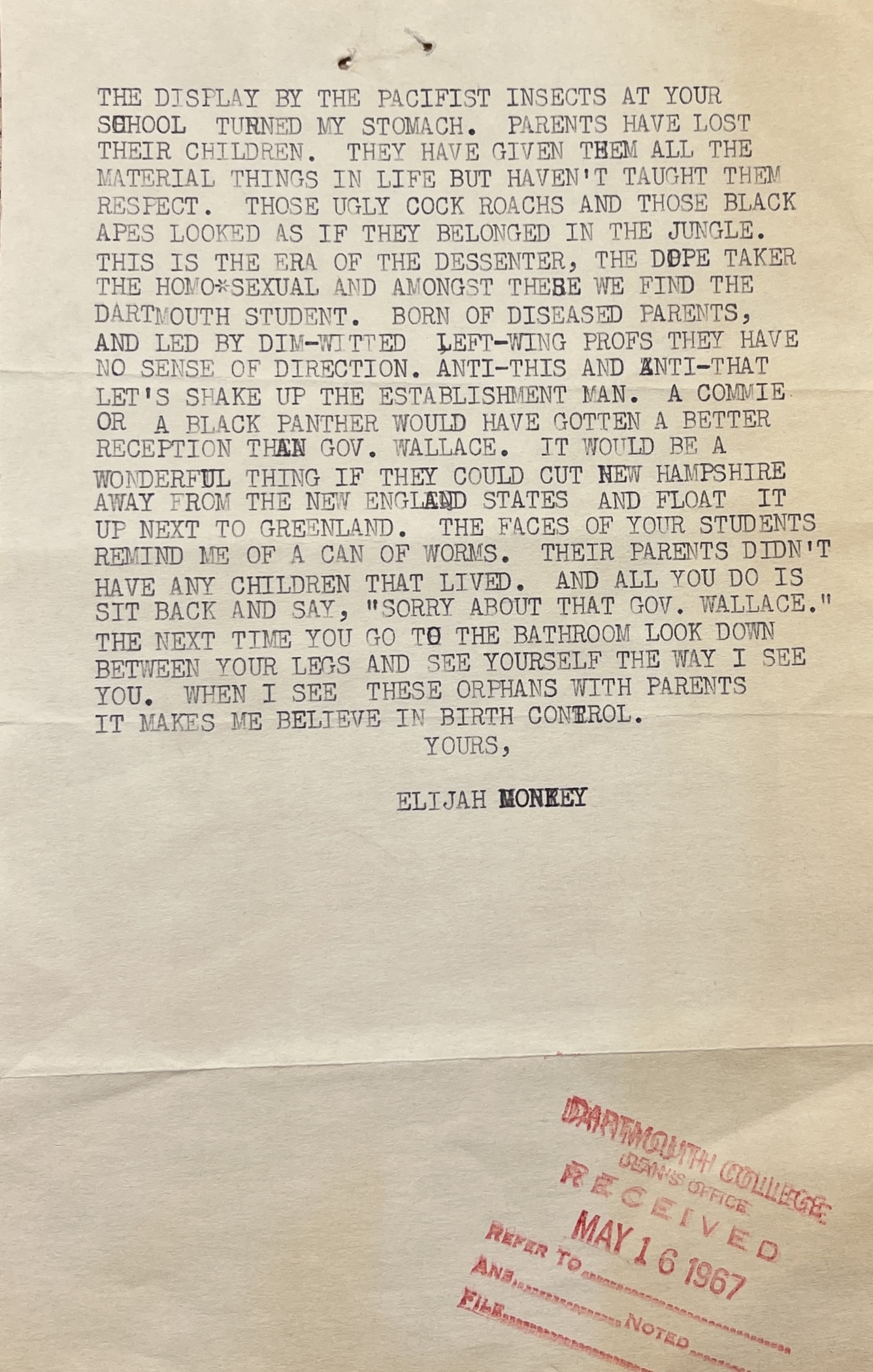

The Alumni Letters:

Not only do these letters reflect the turbulent period of racism and prejudice by white America in the late 1960s, but they also represent the hatred and discrimination heralded by some of the nation's elite. While the language in these letters proved extremely derogatory and malicious, Wallace Ford found community in other forms.