Finding a Home

Finding a Home

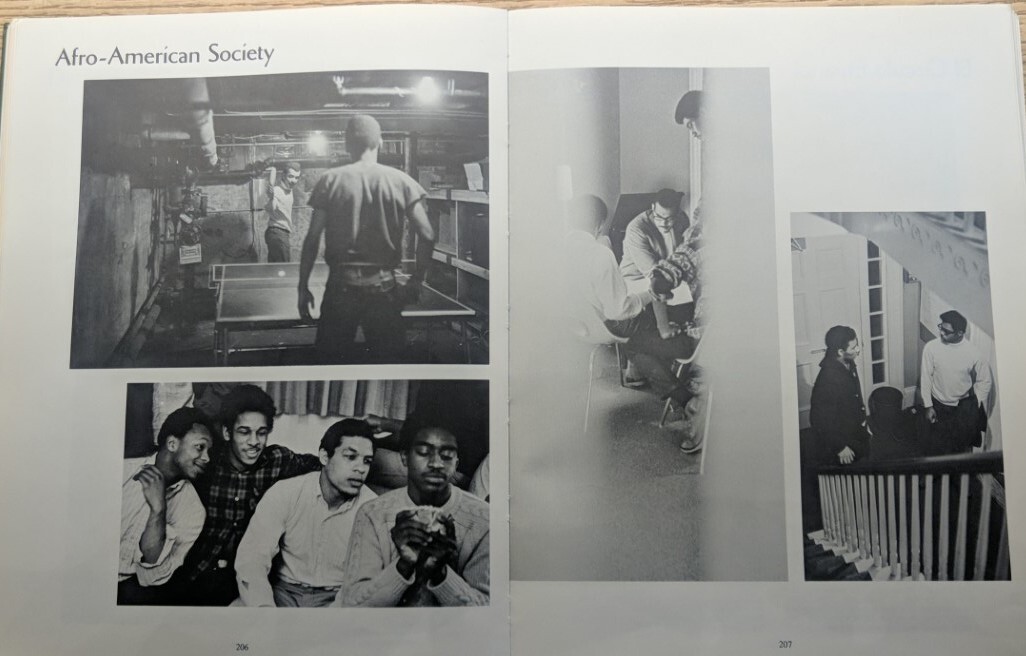

Dr. Copeland's largest impact on the Black community came during his time as President of the Afro-American Society (Afro-AAm) his junior and senior year. The Afro-AAm was created in 1966 after Black Dartmouth students were inspired to confront, head on, the issues Dartmouth’s campus was facing with racism and discrimination on a institutional and interpersonal level (formally recognized in 1969). The society was inspired by Columbia University’s Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS) which was established just two years prior.

Columbia’s society was created in order to get Black students on the campus to think about their Blackness and their Blackness in relation to being in a majority white space, rather than being apathetic towards it. Black Dartmouth students saw this and wanted to do the same. According to Upending the Ivory Tower, they wanted to assimilate to the "things of their choosing" without losing the important aspects of their heritage and this is what the society’s first president, Woody Lee, aimed to do with the Afro-AAm's creation.

According to Dr. Copeland, the purpose behind the AAm was community and a headquarters for Black freedom and activism on campus.

“The majority of us, we were first generations going to four year schools, we were in kind of a foreign environment. And we felt that we we wanted to, in collaboration with the institution since it was committed to this this effort, to integrate their campus, that we wanted to make it culturally responsive and relevant and that we were the experts on what we needed. So our job was to formulate and identify barriers in whatever form they came, create solutions that we felt would be scalable and impactful and then meet with administration to bring those to their attention, and then to lobby ... to help those things get adopted and then implemented over time."

Dr. Ronald Copland, former President of the Afro American Society on the framework behind the Afro-AMM

By the time Dr. Copeland became president in his junior year, the first version of the McLane Report (1968) had been out for a year. This report was Dartmouth trustees' way of showing, after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, that they were actively thinking about ways to help Black students on campus. This was, arguably, the most extensive report submitted on the matter by any Ivy League school and was the combination of observations by students and those who were in charge of the college.

The McLane Report embodied the history of the issues researched, such as race relations after World War II, and connected them to how Black Dartmouth students were fairing in the present. The result was proposals for how to improve campus life for disadvantaged Black students.

So, when the time came in 1970, the Afro-American Society asked Dartmouth to approve a housing community for the African-American population on campus in order to create a safe space in which Black students could come to live, reflect, and be together.

The acceptance of Shabazz [now the Shabazz Center for Intellectual Inquiry] by the college was another example of Dartmouth's willingness to help Black students' transition to campus once they were recruited. Dartmouth was receptive to the majority of requests made by Black students, so it was possible for the Afro-AAm to work in tandem with the institution to accomplish their goals, for the most part, rather than being on completely opposite sides. For this reason, it can be concluded that Dartmouth was well ahead of its peer institutions when it came not only to integration but inclusion.

“If they had said, ‘absolutely not you're not going to have a dorm to yourself, and if you do you're absolutely not going to name it after El Hajj Malik El Shabazz and bring the Black, Muslim orientation to this and upset our community’ and so on. They could have said all those things, but they didn’t.”

Dr. Ronald Copeland

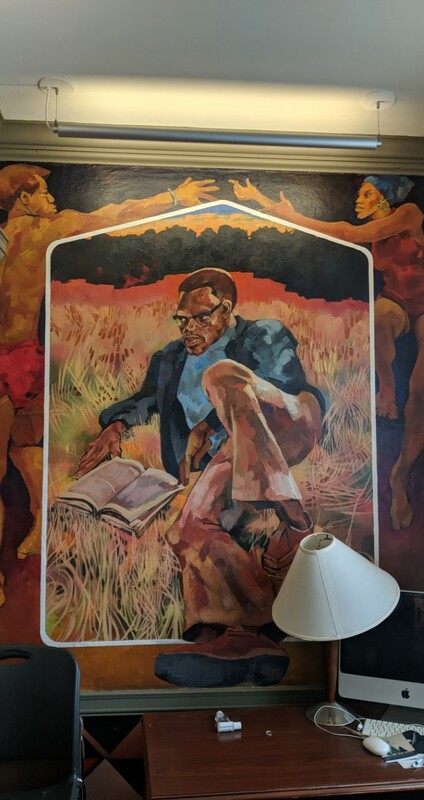

The Temple Murals

Art was another way for Black students on campus to express their Black pride. The Afro-American Society did this through the Temple Murals. The El Hajj Malik El Shabazz Temple, formerly known as Cutter Hall, and most commonly known as Shabazz, was originally housing for international students and those interested in international affairs. Once approved by the college, the Afro-AAm decided to add pieces of art work to represent their mission. Dr. Copeland, president at the time helped lead those efforts.

Dr. Copeland and the AAm knew that one of the things Dartmouth was most famous for was its intricate Orozco Mural Room. As such, the AAm decided to do something similar for their new home base. Florian Jenkins was commissioned by the society to do four to five murals that represented the building's namesake, Malcolm X. One of them, an image of Malcolm X lying to a field reading a book, holds extra significance to Dr. Copeland because he was the model for Jenkins so that he could get the image correct.

“When people are talking about those murals in my presence, it always hits me in a special way, one because of my love of art in general and then specifically because, for that particular mural, that, I believe, is still there today, I was the person who modeled for that and most folks have no idea about that.”

Dr. Ronald Copeland