"They Didn't Want Us and We Didn't Want Them": The Foundations of the Afro-American Society

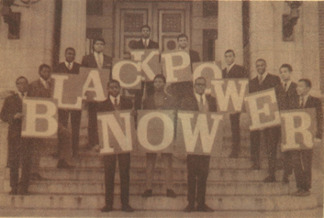

During my interview will McCurine, he revealed that he was one of the many founders of Dartmouth's Afro-American Society (also called the AAm, AAS and Afro-Am). During their time at college, Black undergrad students often faced discrimination by white fraternity organizations. On the topic of fraternity spaces, McCurine recalls, “Well, oh, one we didn't relate to the fraternity culture and a lot of the fraternities were racially segregated. They didn't want Blacks and we were young, proud Black men; they didn't want us, and we didn't want them.” Rather than assimilate to the white status quo, a group of Black students created the Afro-American Society in 1966. Bradley attributes the inspiration for this to Columbia University’s Student's Afro-American Society (SAS) (152). The AAm became an outlet for Black students to express their identity and needs as a community and an opportunity for Dartmouth students to join the Black Power Movement.

Ugoji: So what role did the AAm play to Black students at Dartmouth, what was its role?

McCurine: It was really the center of our social and political lives. We would host parties and have Black women from other schools come up, or we would travel together to road trips, where other Black student groups are having social gatherings. It was as important as fraternities are to its members. The Afro-Am was to us, it was the center of our social life

The Political Arm of the Black Community

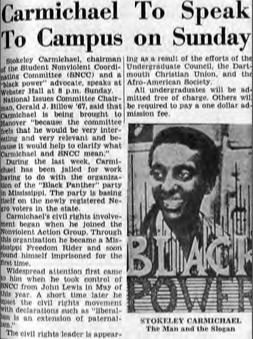

Immediately after the founding, The Afro-American society became the political platform for Black students to protest discrimination and the Vietnam War and, amplify youth voices. Members of the AAm joined Dartmouth’s chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) to protest across campus for the end of the war in Vietnam (Bradley, 153). Students learned that the college had thousands of dollars invested in Eastman Kodak, Inc. which refused to hire Black workers. As a result, 1967, the AAS organized sit-ins in administrative offices to advocate for the institutions divestment from the company. Members of the organization also invited Kwame Ture (formerly Stockley Carmichael) to campus in 1966 and in 1967 led protests during the George Wallace’s return to Dartmouth. Unlike other Ivy League institutions of the time, Dartmouth did not have highly militant or dramatic rebellions. However, in part due to the nonviolent and institution-centered methods Afro-American society, civil rights and Black power were ever present in the woods of Hanover, New Hampshire.