Discrimination and Resistance in the Classroom

Classroom Prejudice

Though breaking the barriers to accessing colleges like Dartmouth was pivotal, working to gain entry to these elite institutions was only the beginning of a long, arduous journey. Black students at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) experienced myriad forms of discrimination, from microaggressions to explicit racism, which sometimes even escalated into direct violence (Kendi 60). While many of these harms were present in informal social interactions between students, discrimination in the classroom was (and is) commonplace (Simpson 3). This page explores the forms of racism experienced by Black students academically, starting with experiences within classes and involving faculty.

During the mid-20th century, racial, economic, and social issues in the United States were coming to a head. The intersectional causes of Civil Rights, the anti-Vietnam War movement, and widespread economic and gender inequality deeply affected the lives of many Americans. However, when Black students attended PWIs, they found that attitudes of racism and sexism were deeply entrenched everywhere.

Specifically in their academic lives, they often encountered direct ideological conflict and grade discrimination by professors. In I Have Been Waiting: Race and U.S. Higher Education, Jennifer Simpson points out that the “invisible”, “normalized” attitudes of white supremacy and white identity frequently caused the exclusion of Black students from intellectual inquiry, equitable class participation, and overall achievement. Some students, like Wesley Pugh, directly resisted these harms at Dartmouth:

“I said ‘Black people,’ and I capitalized ‘Black.’ And [my professor] called me in and said, ‘you can't do this.’ And I told him, ‘I'm not going to use lowercase for Black people.’ And he explained the grammar rules. And I explained to him the issue of Black pride, and the fact that— look, I'm referring to a people, a group. And he recommended that I be moved from his English class, and I was put into another English class.”

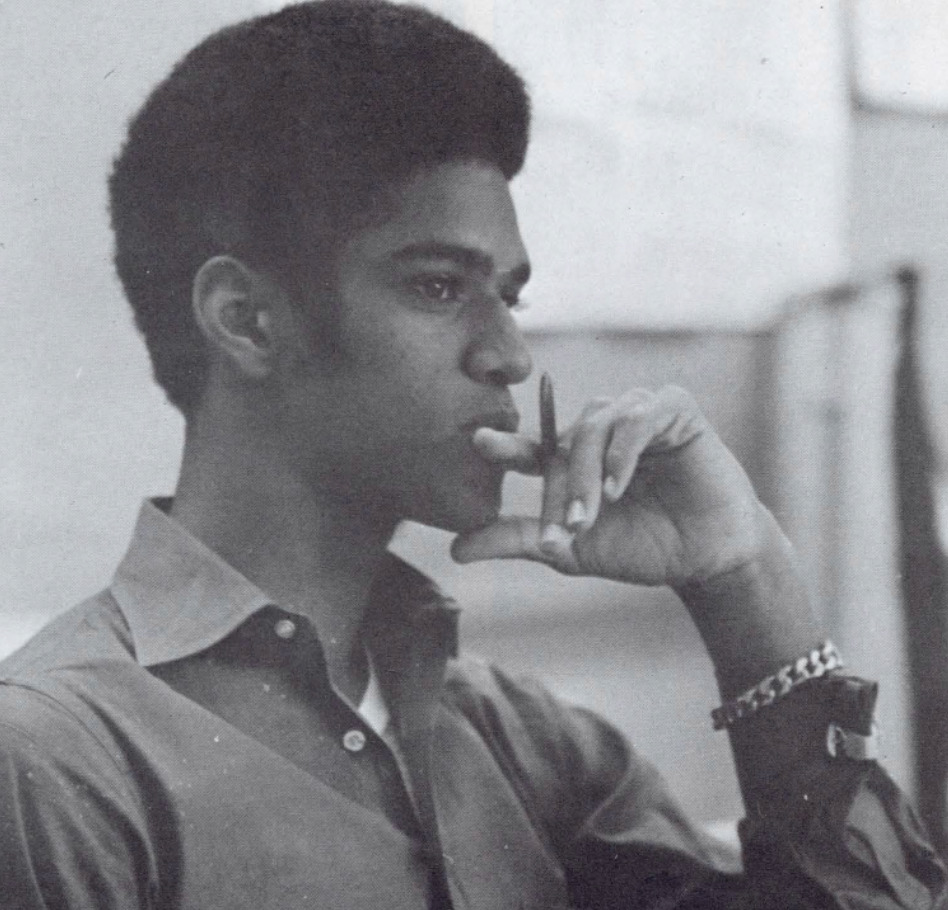

Wesley Pugh '73

Students at other schools, like Keni Washington, also experienced prejudice in the classroom. In his interview for the Black Alumni Stories oral history, this Stanford ‘68 cited many negative experiences. As a music major, he was disheartened when his professor ridiculed jazz music in his class. At the time, William Shockley was also a professor at Stanford. Shockley, who worked to prove the “genetic inferiority” of Black people, also visited Dartmouth, where he was met with widespread protest and resistance. As a Stanford student, Washington regularly encountered Shockley:

“I would see Shockley on the campus and every time I’d see this guy after I first heard him speak, I would feel like, ‘Oh my God, why is he here?’ No, I take that back. I didn’t say, ‘Why is he here?’ I didn’t say that. That’s incorrect. I would say at the time, ‘Wow, he’s here, and maybe I don’t belong here because he is part of the Stanford community. He is a revered part of the community, so maybe they don’t want me here.’”

Keni Washington '68 (Stanford)