Acts and Laws

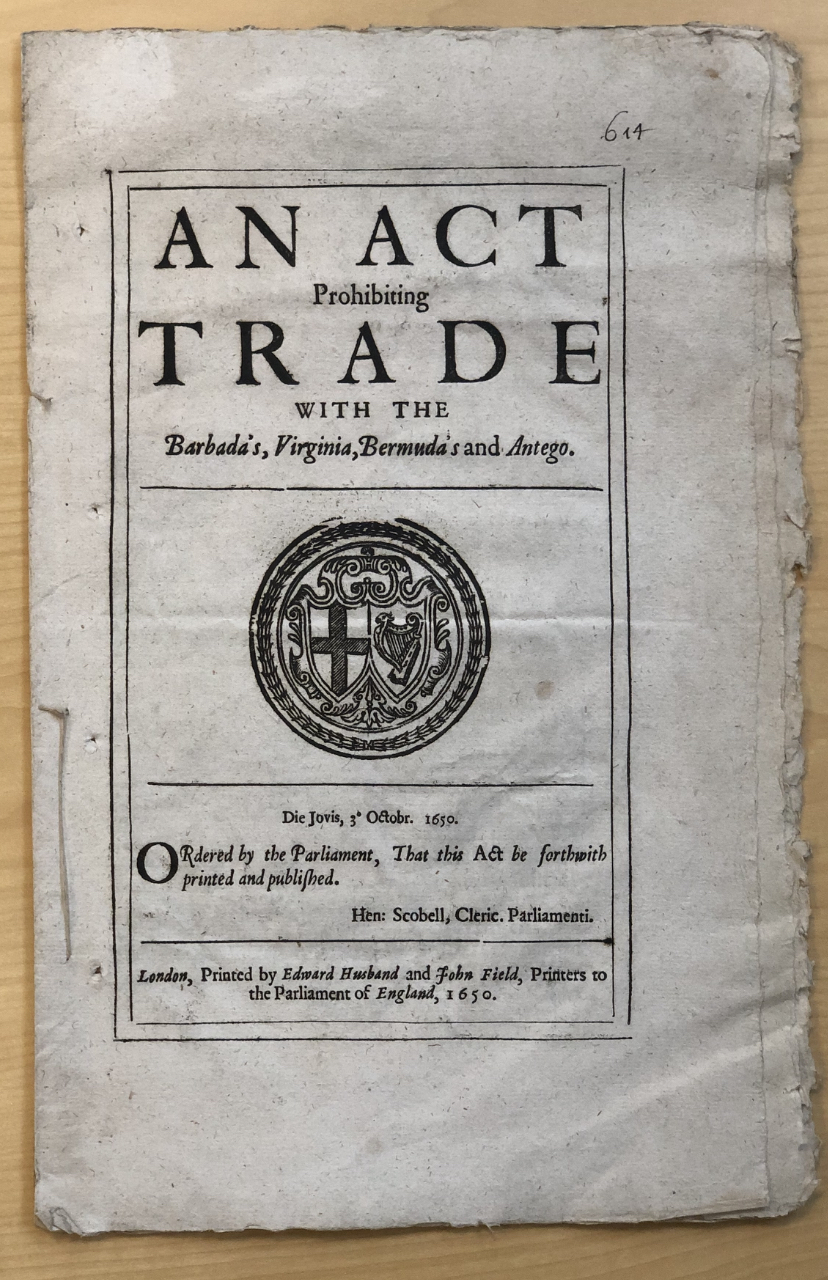

This act was passed in 1650 from the first parliament after the execution of Charles I. This was an act passed by parliament against English colonies that sided with the crown or failed to choose a side during the conflict. Newer settlements like the one in Massachusetts were parliamentarians, and thus were not placed under the embargo. However, the older colonies were loyal to the crown, and thus were included in the embargo. The attention of Parliament was not immediately focused on the colonies, as it had to consolidate power and ward off royalists from Scotland, Ireland, and many islands. The settlements that had been created by the Virginia Company were conspicuous in their views on parliament as opposed to the king and were placed under the embargo. The act gave people commissioned by parliament to stop and seize any ships, domestic or foreign. It also says that it’s illegal for foreign ships to engage in trade with the prohibited colonies without expressed permission of parliament.

This item outlines the events of a trial of three Quakers (William Robinson, Marmaduke Steavenson, and Mary Dyer) in the general court of Massachussets in 1659. The three quakers disobeyed the court’s orders to leave the colony, so they had to go to court again. This item is intended to inform people of the proceedings that occurred and the punishments that were enumerated (death penalty for Robinson and Steavenson, banishment for Dyer). This document serves as proof for anyone who is concerned about the verdict, but it also sets a stark precedent on the authority of the court and what would happen to people who disobey it.

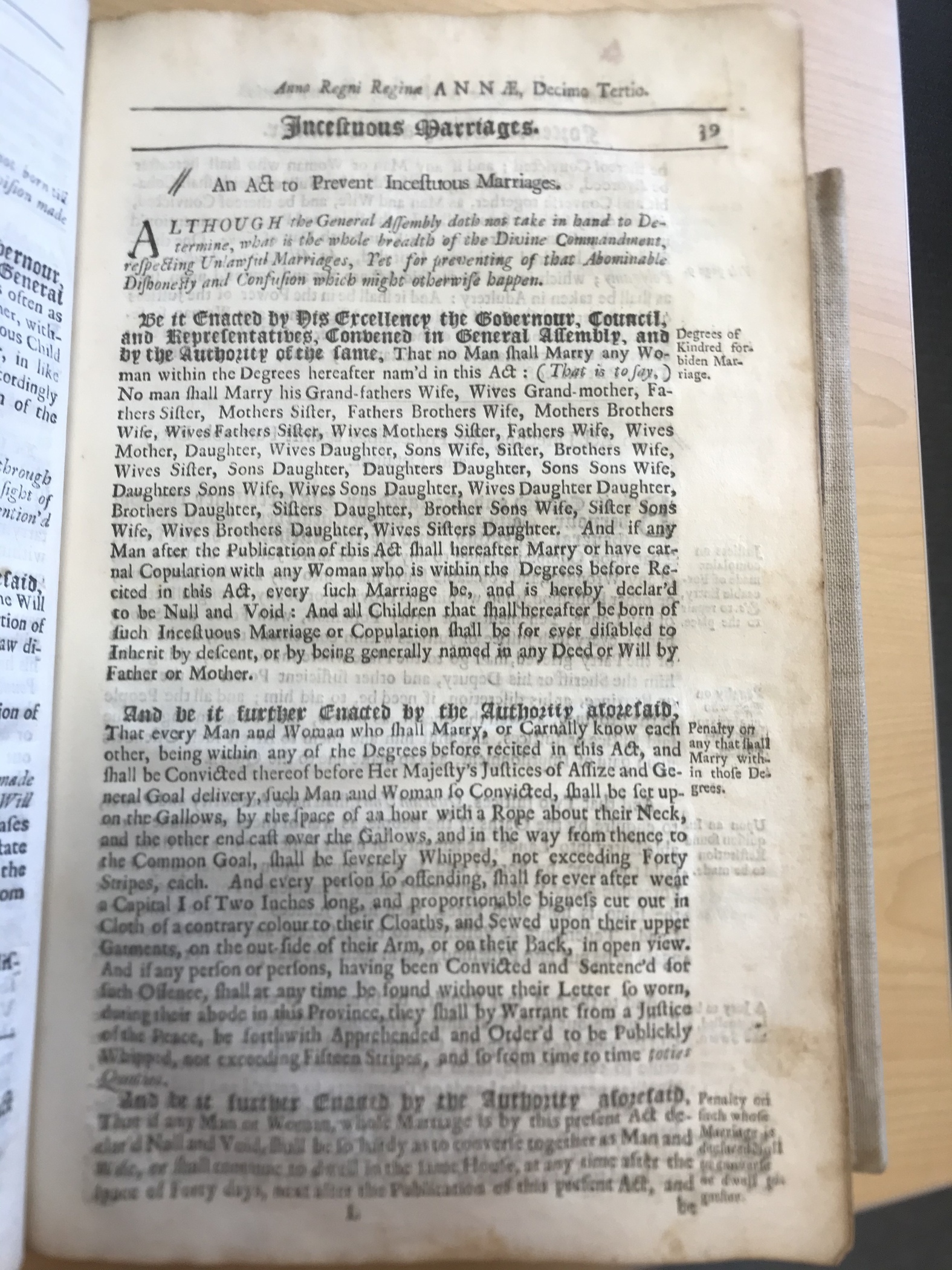

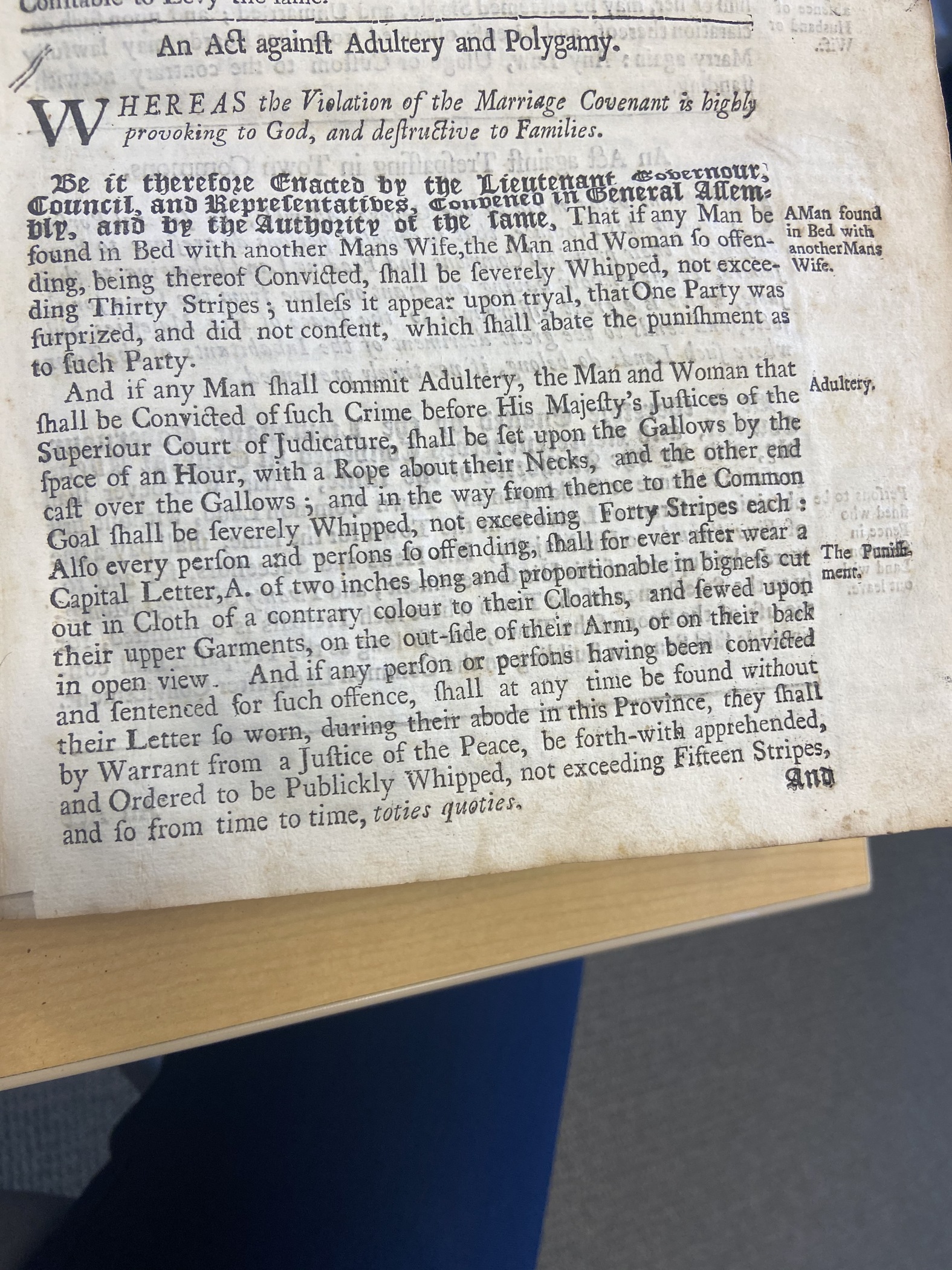

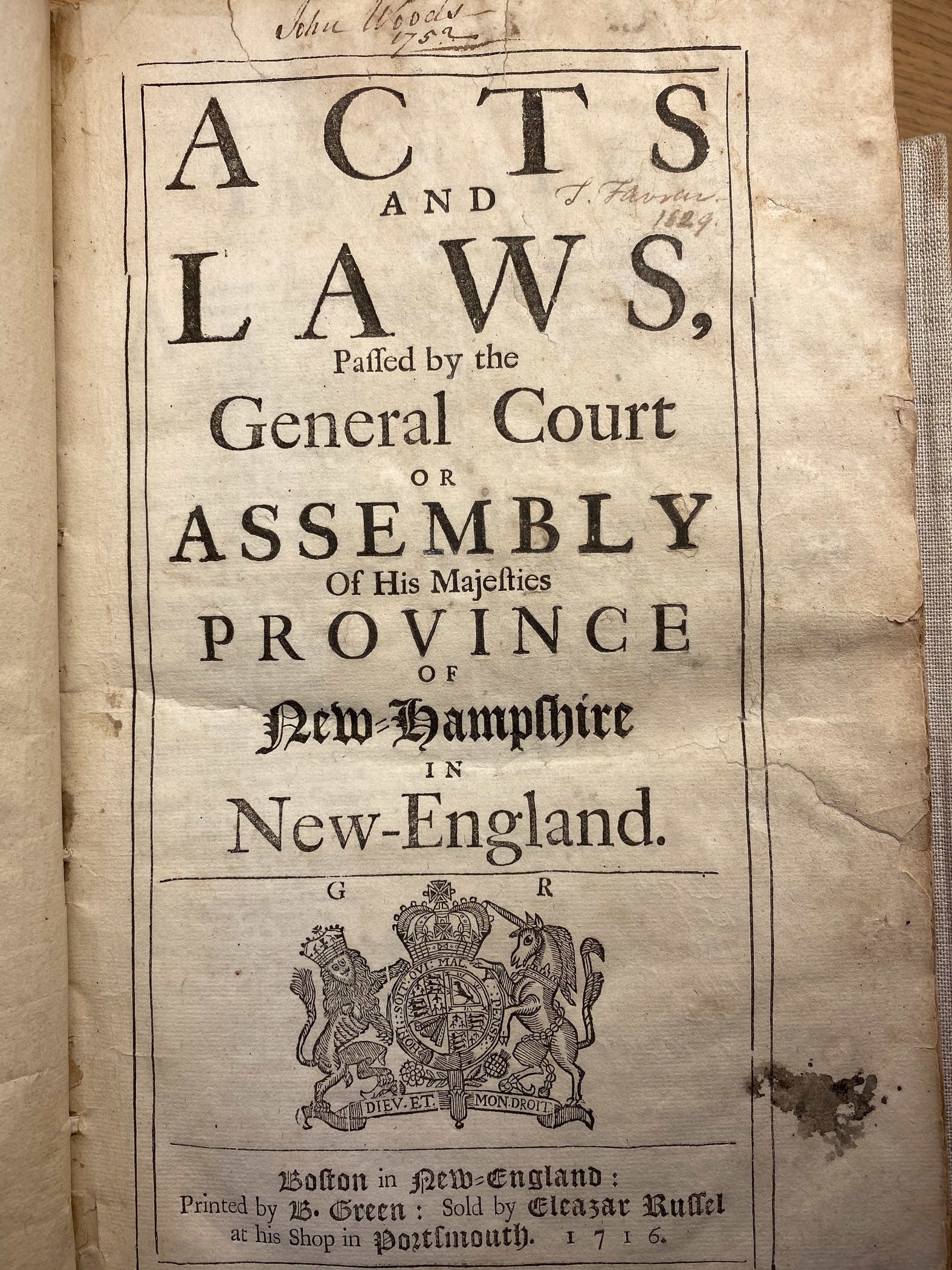

Though British American colonies were still technically bound to the common laws of England, law developed somewhat organically in the colonies as and when certain issues arose. The physical space between the mother country and its colonies as well as the wide degree of variation between England’s concerns and those of the colonies resulted in the evolution of a colonial law system that developed adjacent to common law – not completely outside it, yet not strictly following it either. The precise concerns that colonists had over land and farming, relations with Native Americans, and the construction of a social order did not align with England’s established laws. Furthermore, as religion played a fundamental role in some colonies, negotiating the tenuous line between religious and secular authority proved a tricky balance. In this tome of New Hampshire laws, we are introduced to the topics that concerned citizens, including property rights and trial procedures. Interestingly, there are no laws pertaining to witchcraft, which indicates that at the document’s publication, citizens consciously supported the separation of superstition and abject religiosity from civil and secular law. (Dugar)

Further reading: Pagan, Anne Orthwood’s Bastard: Sex and Law in Early Virginia (2002)

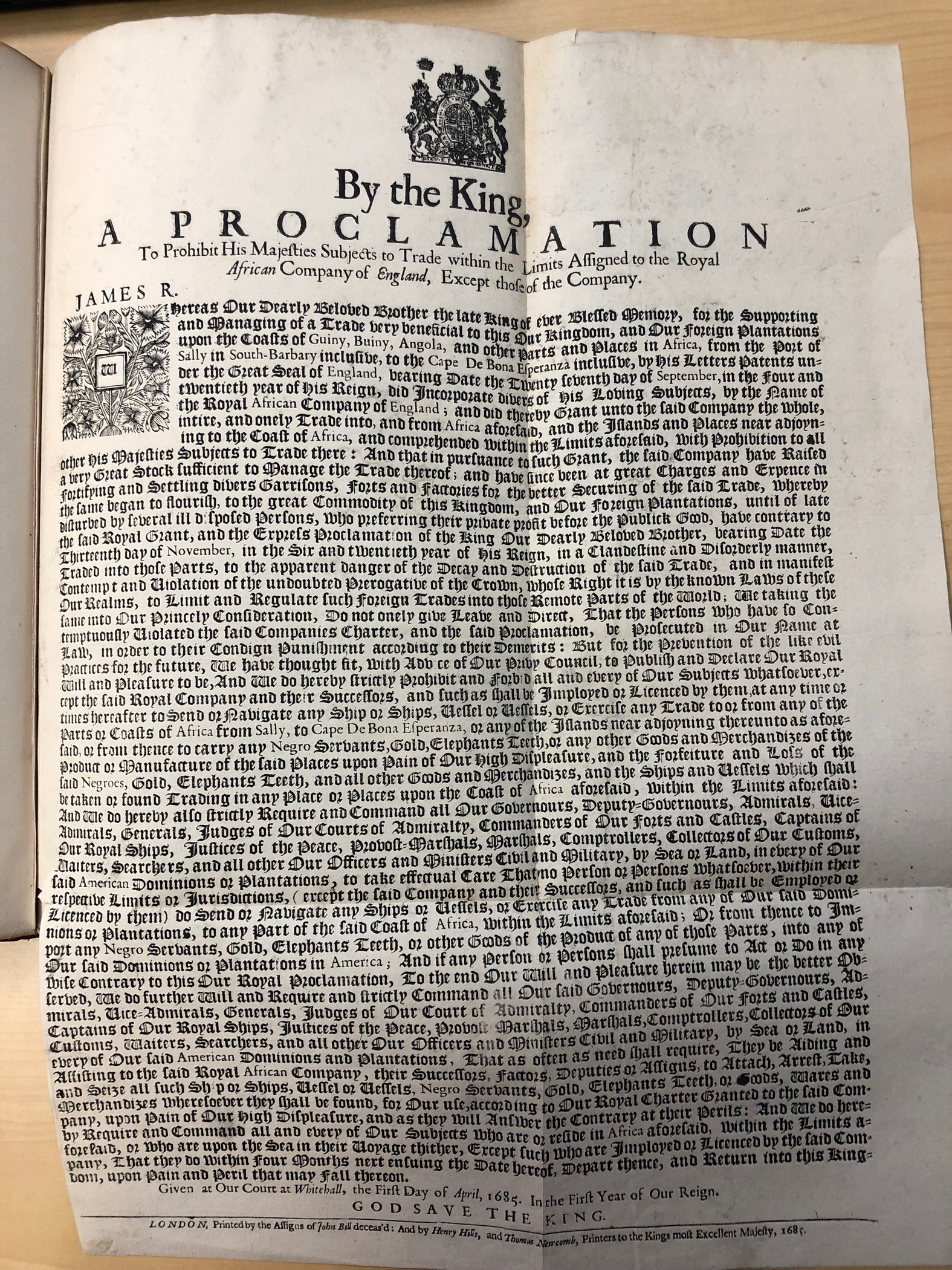

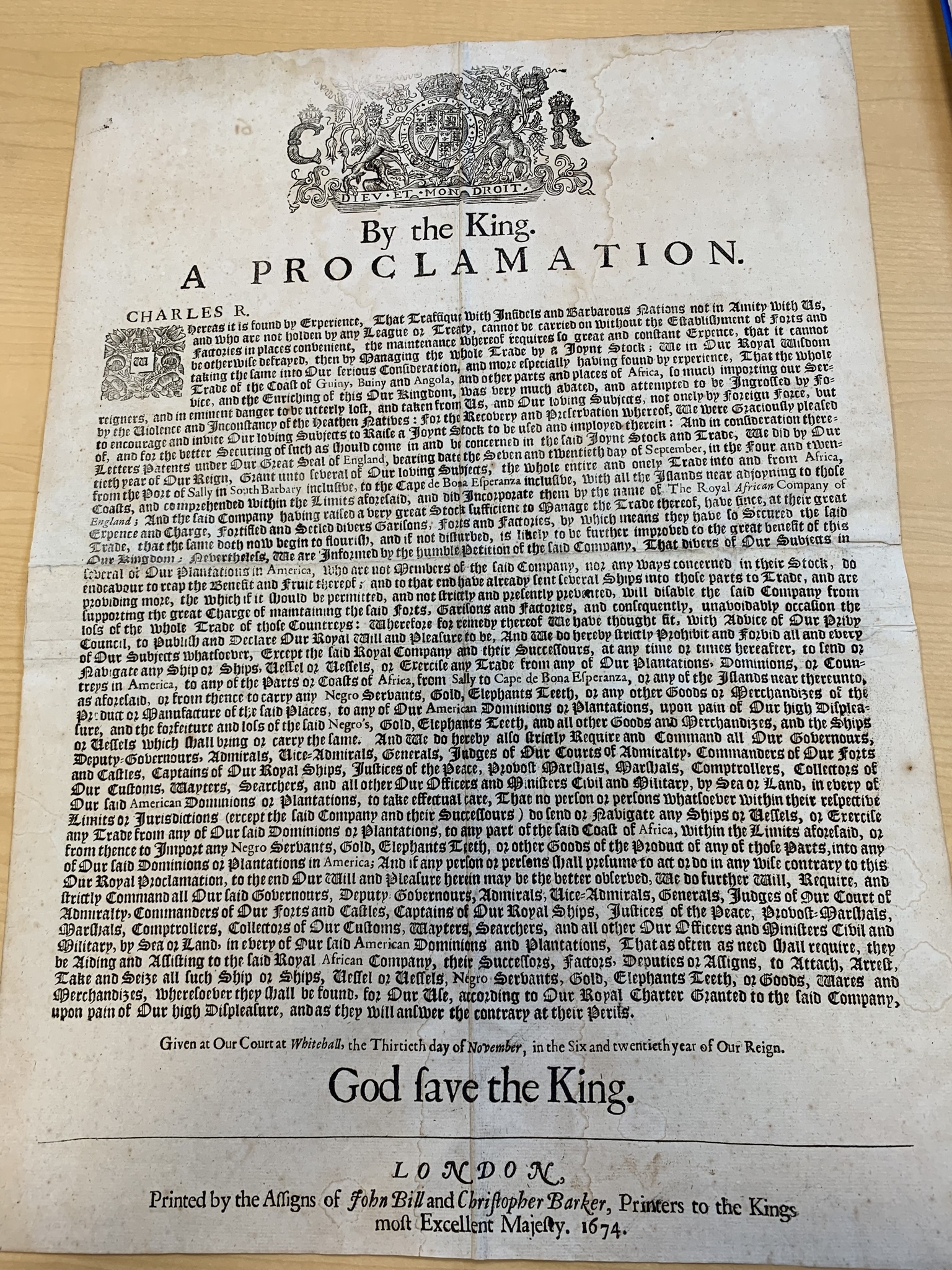

This Proclamation prohibited trade outside of the Royal African Company. It helped to monopolize all trade amongst the colonies. This is significant because it demonstrates England’s desire to control its colonial imports and exports. This is how the English decided to cope with the idea of needing to more closely control the colonies. It was important that all trade that took place happen only within England’s control. This would encourage economic growth in England, but it also stagnated the opportunities of those living in the colonies. This shows the amount of control that the English sought to have over their colonies. (Brillante)

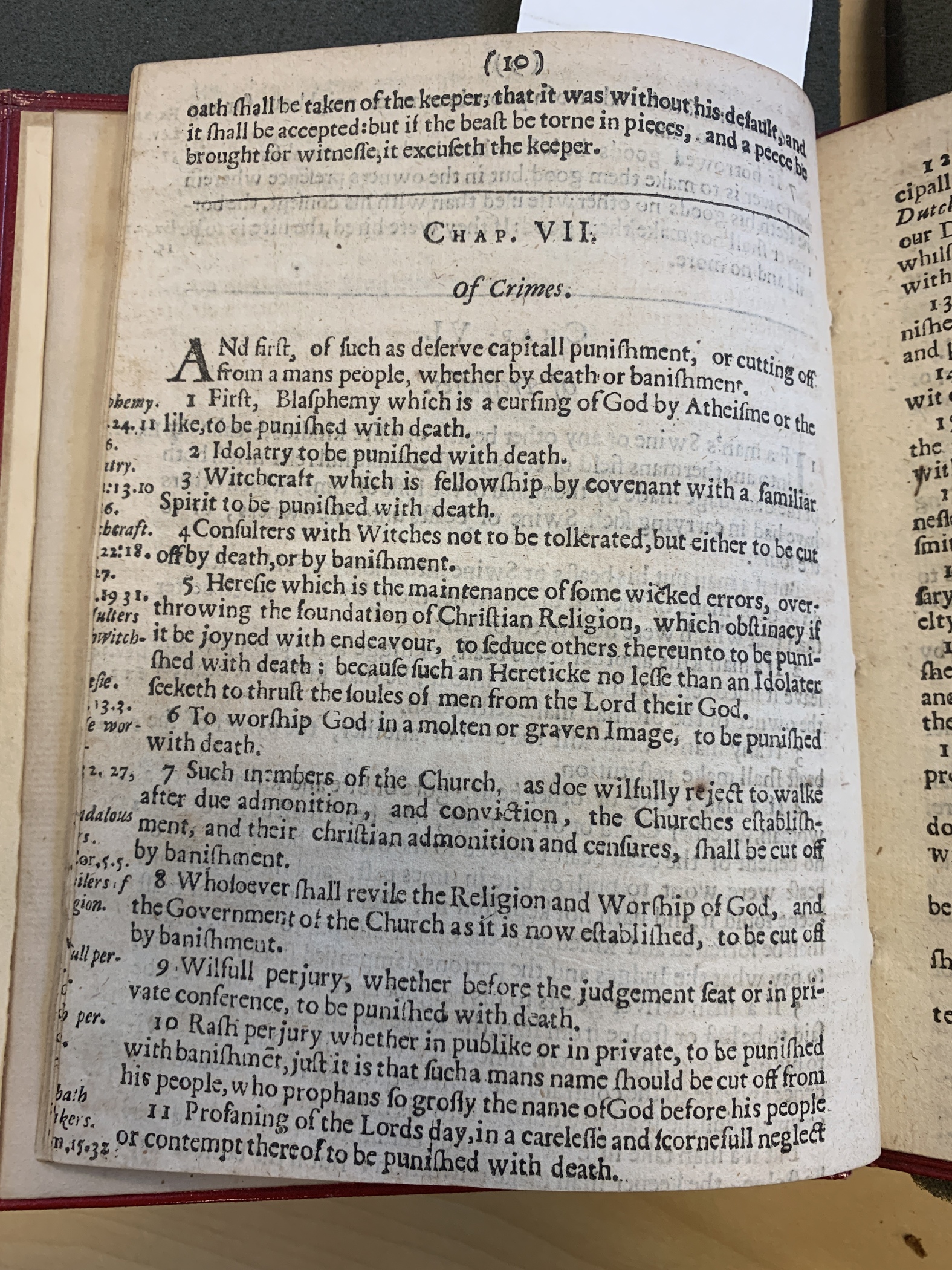

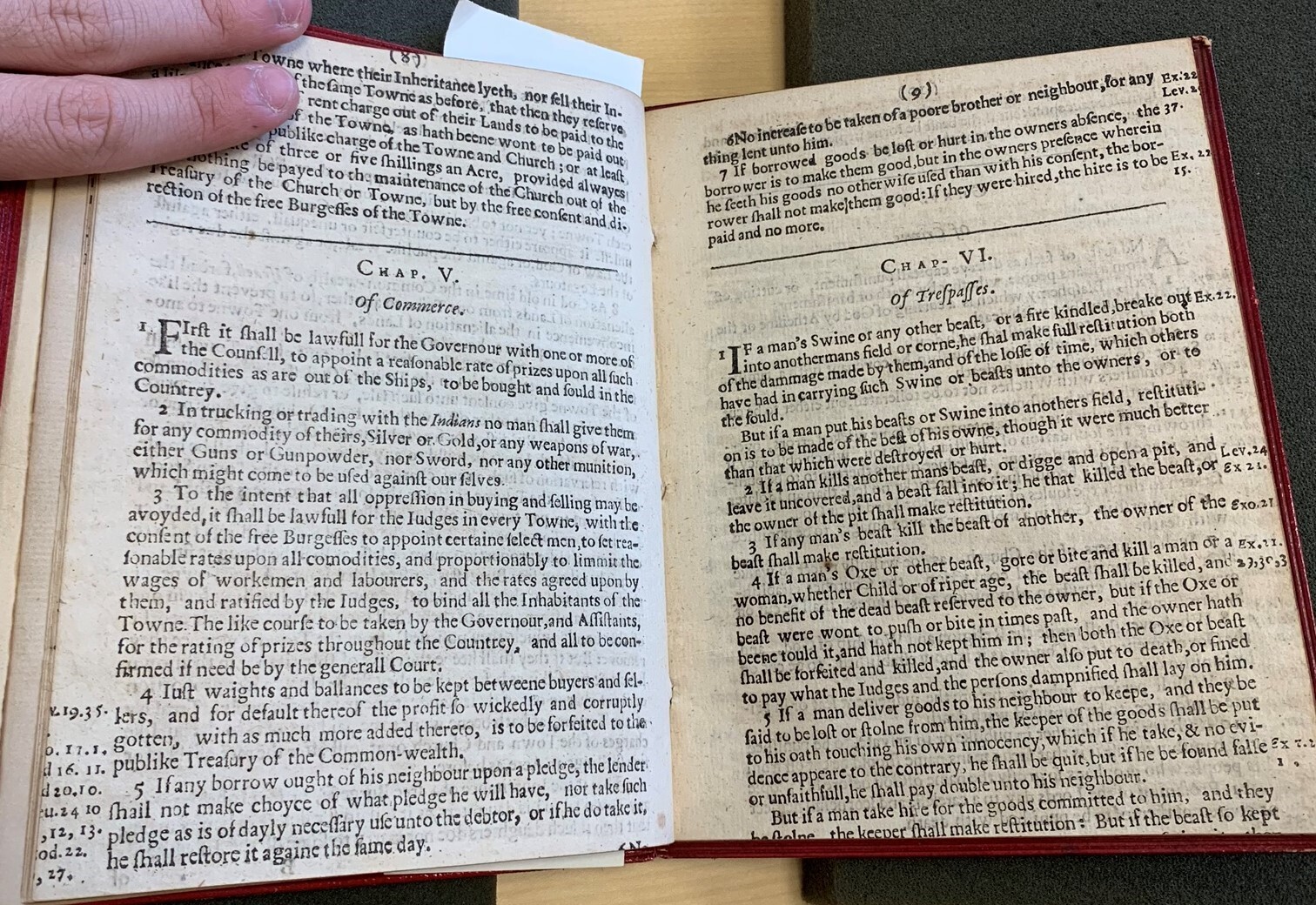

John Cotton, the author of Gods Promise to His Plantation, is also the creator of this item.This abstract contains a general description of the laws in New England in the mid 1650s. It is laid out in chapters, with each chapter enumerating the laws pertaining to a certain group of people. There are chapters detailing laws relating to magistrates, burgesses and free inhabitants, the protection and provision of the country, the right of inheritance, commerce, trespasses, severe crimes, minor crimes, and the trial of cases. It’s really an overview of the entire system of law in New England at the time (1641). This item would be particularly interesting to people who are trying to compare the legal system in England to that of New England. At this time, new England was supposed to be following the laws of England, but they were acting as a sort of commonwealth, with laws that weren’t necessarily the same as England (Golin).

This summary of commercial laws set forth regulations over what could and couldn't be sold, along with who is in charge of future commercial statutes. #2 on the list, for example, outlaws the sale of guns or silver or gold to Indians. This piece of legislation is important because it allows the colonists to maintain a clear competitive advantage over the Indians, who themselves held competitive advantages in other ways, like in their knowledge of the land or with their willingness to attack in more scattered, unorganized ways. #3 writes that local burgesses and judges have the power to set prices and wages. Such a law like this would have been a large assertion of colonial authority because anything that is written into the powers of a local body is therefore not merely deferred to the Crown or Parliament, or the ever-vague common law. This document was published in 1641, during the rule of Charles I, at a time when the English were not so concerned with the affairs and economy of its American holdings as they would be in the later half of the century. This lack of care would have allowed New England to assert its authority to regulate its own economy, like they do in this document. (Marc Novicoff)

This document is the royal charter for the Royal African Company. It set up the jurisdiction of the RAC as extremely broad from "South Barbary [on the North African Coast] to Cape de Bona Esperanza [the southern tip of Africa]." Not only was that their jurisdiction broad, but the RAC was given an official monopoly on Anglo-African trade. The English’s actual and regulated participation in African trade (especially slaves) was a big deal because of previous Iberian and Dutch dominance in that sphere. It also represents another shift in English policy—how close they should be to the actual enslavement of people. When the English had merely bought or stolen slaves from Iberians, they never considered themselves to be “making” slaves, only taking slaves. They weren’t guilty of enslaving anyone, technically, and their ownership would surely be preferable over the cruel Spanish papists, which is how the English viewed the Spaniards. Now though, the RAC would be on coasts paying money to actual slave raiders; were they not becoming more and more responsible for enslavement? But they had reasons not to care about ethics anymore—by 1674 (the date of this charter), the Barbadian economy was taking off and all the other colonies’ outputs were growing too. Cheap, “expendable” labor was needed and the issue could not wait for pirates to take slaves from Spanish ships. (Marc Novicoff)