Religious Thought

RELIGION IN COLONIAL AMERICA

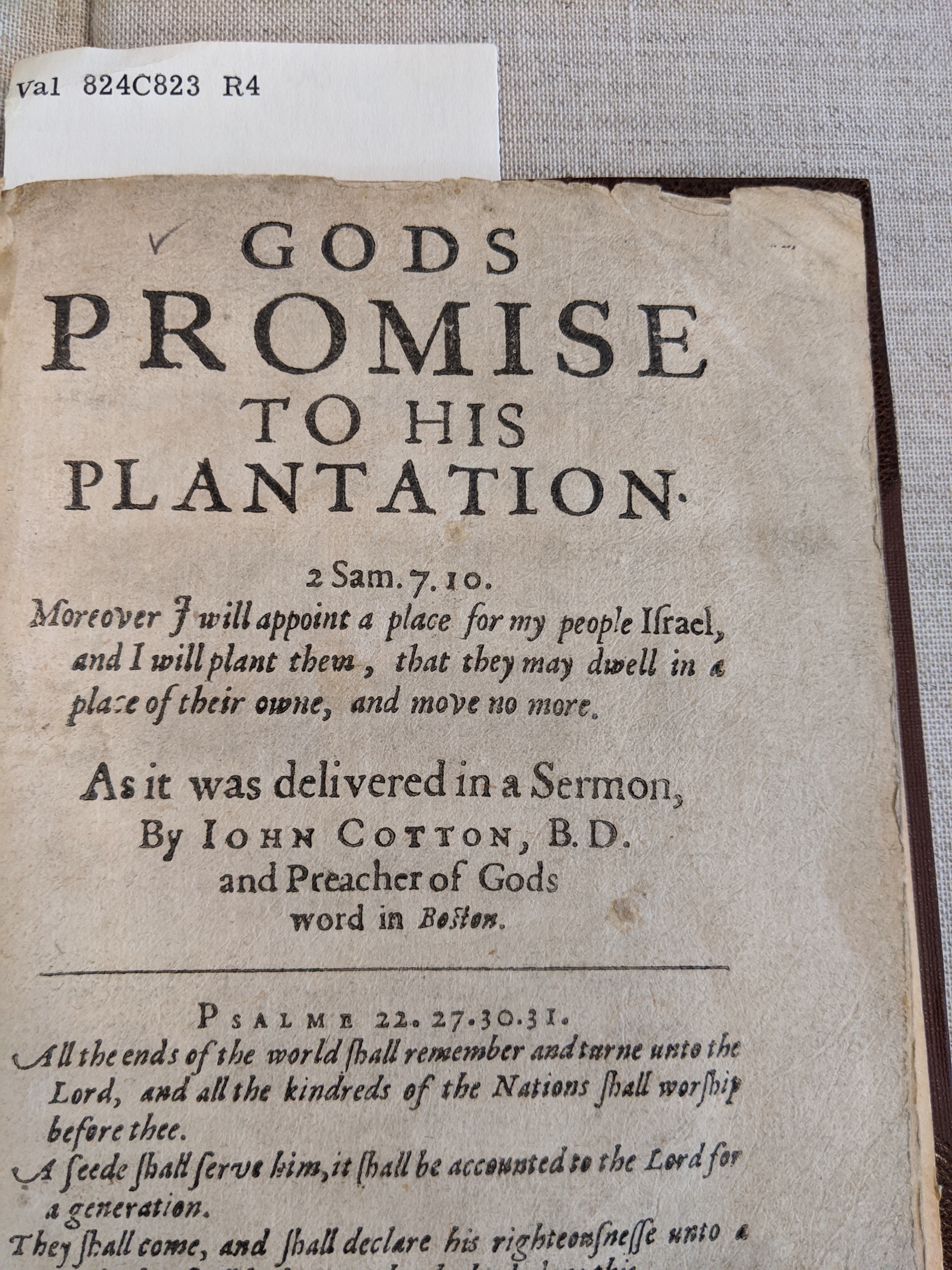

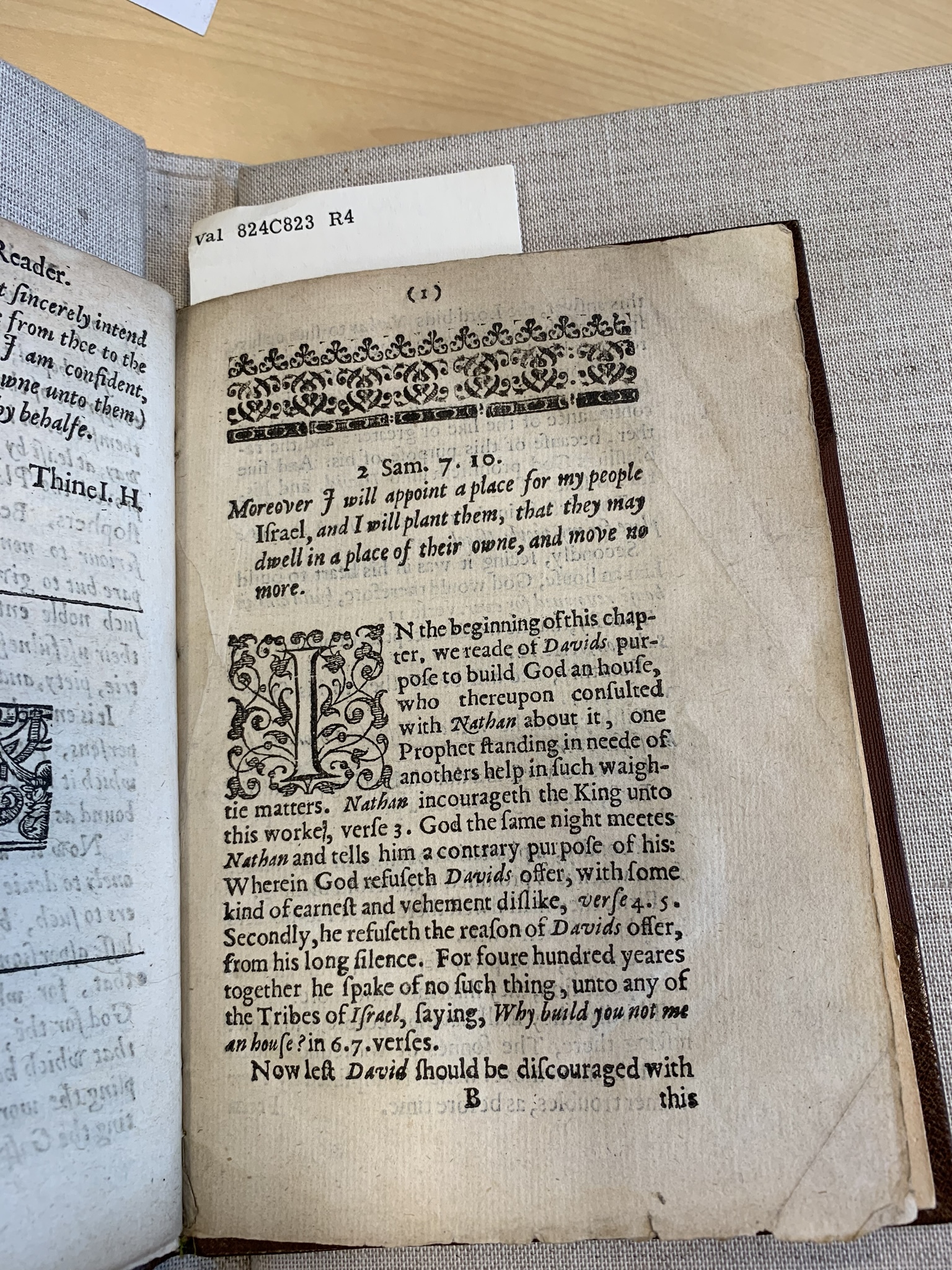

In the Puritan New England of the early- to mid-1600s, religion was synonymous with state organization. Prior to their journey across the Atlantic, Puritans had been persecuted in England due to their contrarian interpretations of the Bible and how the Church of England should be structured. In terms of theology, Puritans subscribed to the notion of “predestination,” a Calvinist doctrine that states that God has already decided who will be saved and who shall be condemned upon death; thus, the most important theological undertaking for a Puritan is determining whether one is, in fact, of the “elect.” While the process of determination differed amongst Puritans, it was widely accepted that a revelatory or conversion moment that comes while reading the Bible is an indication that one is saved. In terms of secular order, because everyone is potentially an elect, the Puritans condemned the hierarchical ecclesiastical order of the Anglican Church; considering the English monarch was the head of this church, this was seen as a threat to the basic structure of British society. Thus, to the Puritans, New England represented a haven free from persecution that would allow for the creation of ideal Purtian societies. (See “God’s Promise for his Plantations,” a providential sermon given by Reverend John Cotton to the Puritans settling in Massachusetts.)

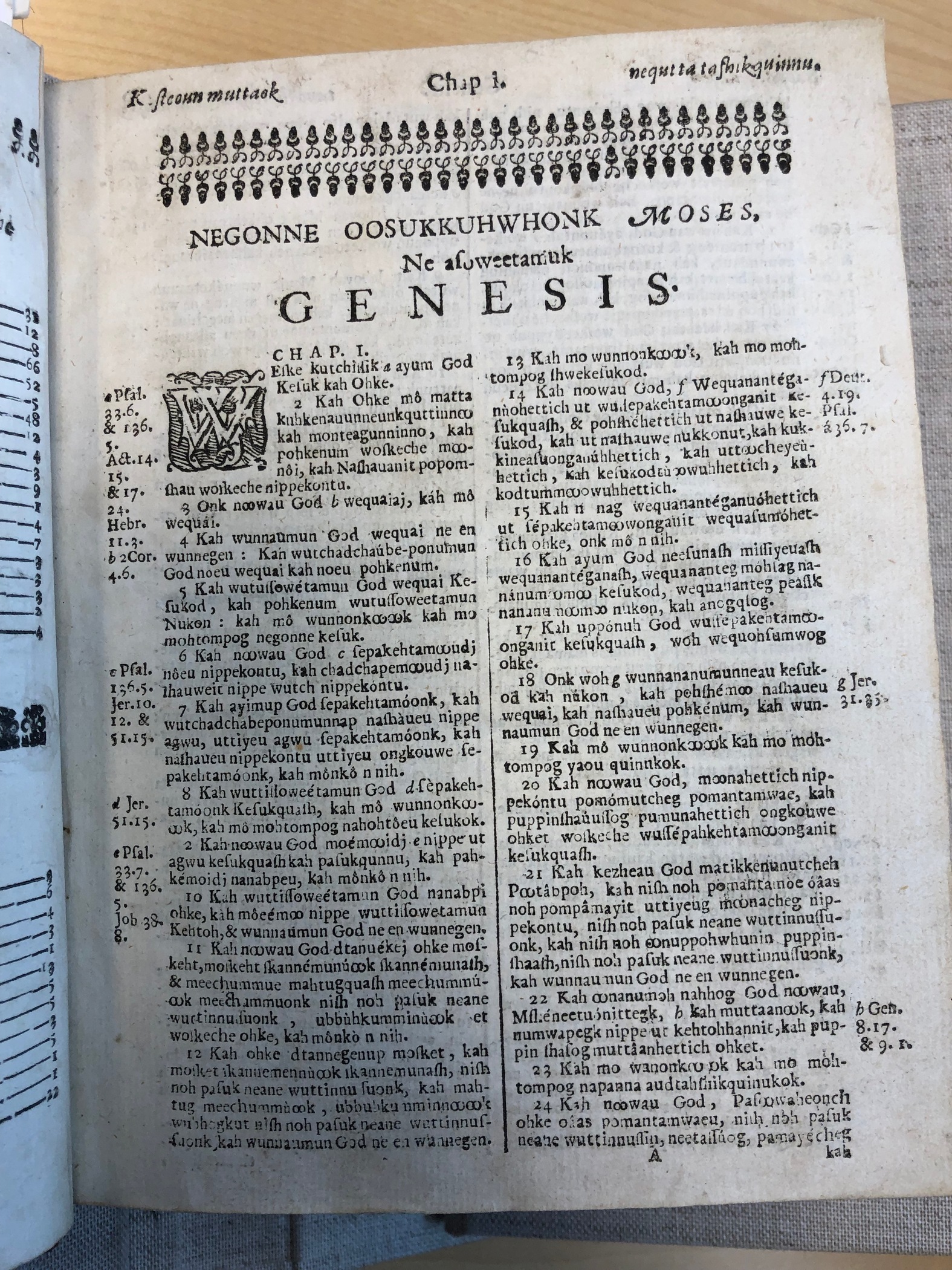

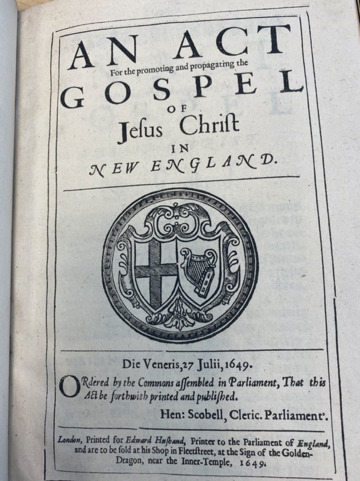

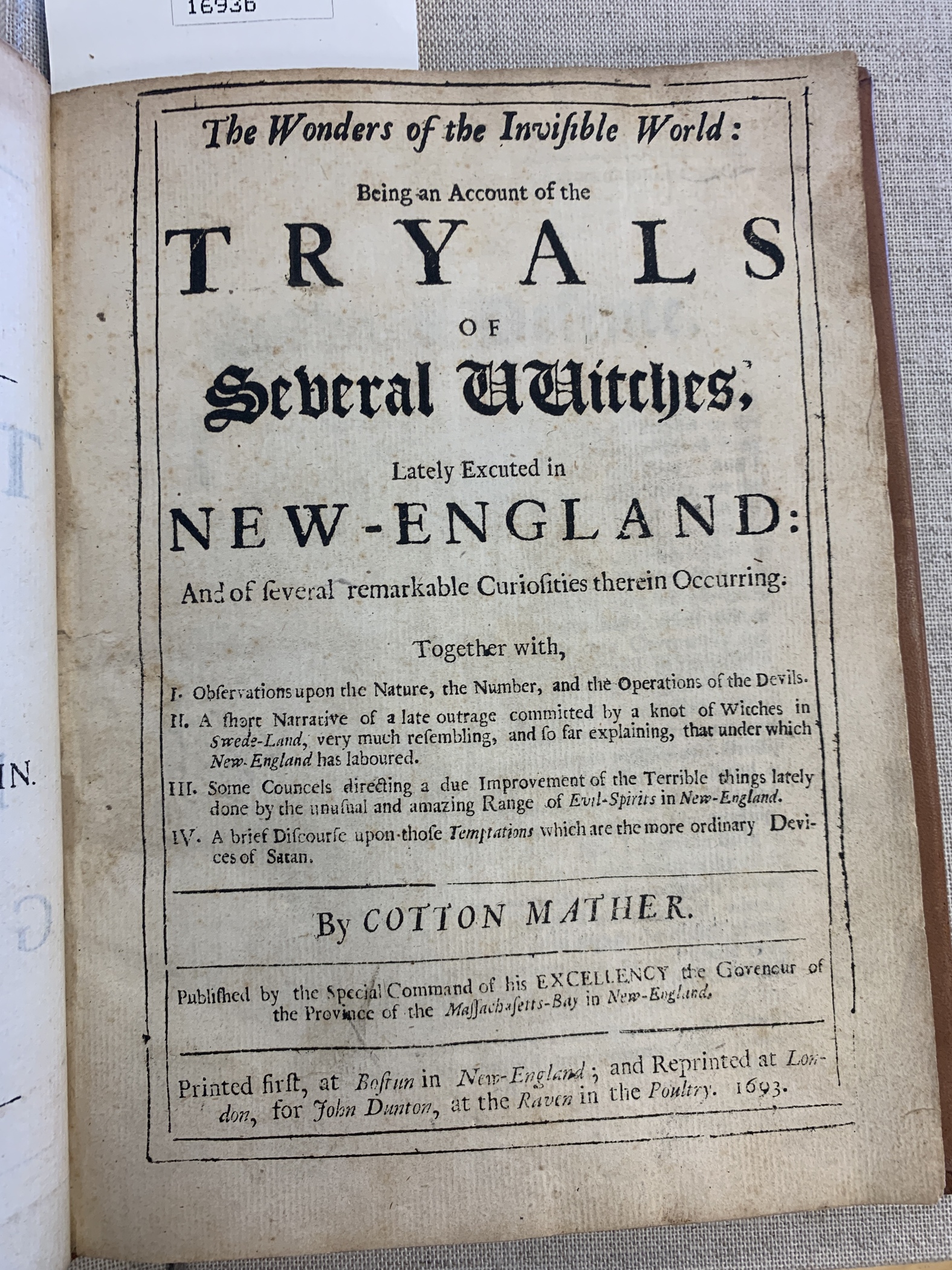

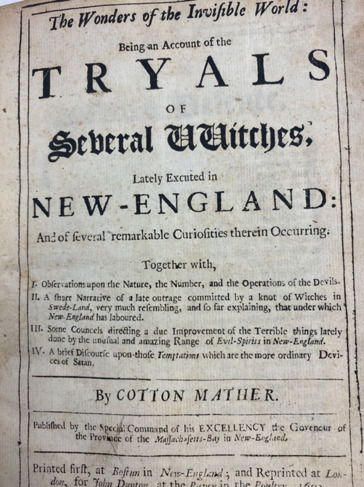

In reality, however, the conflation of church and state that resulted from their beliefs – despite the fact that they, in theory, were against this intertwining – created an atmosphere of constant policing and paranoia regarding those who may falsely proclaim that they are of the elect. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, this kind of ardent Puritanism was on the decline, and many consider radical Puritanism’s last manifestation to be the Salem Witch Trials. (See “The Wonders of the Invisible World.”) Radical Puritanism also informed early conversion efforts in New England. One of the most important goals for early colonists was the conversion of Native Americans to Christianity. For this purpose, Parliament raised funds to establish prayer towns and publish Eliot Bibles. (See "An Act for promoting and propagating the gospel of Jesus Christ" and "John Eliot Bible.")

Religion was interpreted differently in other regions of the Americas, however. In William Penn’s Quaker Pennsylvania, religious liberty was decreed for all. (See “A True Relation for Proceedings against Certain Quakers” for one example of the relationship between Quakers and Massachusetts Puritans.) Even though this society may seem ideal, many merchants used Quakerism to further their personal economic goals – they allowed wealth to inform how they interpreted and behaved within Quaker circles to gain commercial power and influence. Many would also argue that despite Penn’s proclaimed belief in equality, his treatments of the Native Americans of the area were unjust (Dugar stops here). (Brillante starts here) Religion throughout the 17th century on islands such as Jamaica was dominated by Christianity. However, their ideas of conversion were significantly different from those in New England. As previously stated, Puritan views were more focused on maintaining order, while on islands such as Bermuda religion was important for other reasons. Christianity was commonly practiced, but the towns were not so dependent on it for their governing laws. Religion simply provided the moral code that allowed the colonists on the island colonies to justify many of their actions.

For example, slavery served as big question for many. How could slavery be acceptable? Slavery was an important source of labor for many people on Jamaica, especially after the development of the sugar mill having large amounts of labor that could be worked all hours of the day was crucial to the owners of sugar workers. If they did not have slaves they would not be able to run their sugar mills at full capacity, thus diminishing their profits. However, this made the notion of converting slaves to Christianity nearly impossible because one could not enslave other Christians. This means that so long as the slaves that worked the sugar plantations on the island were not converted to Christianity then their enslavement was somewhat acceptable. The other difference that showed significant divergence from the New England colonies was how the religious rules didn’t define their laws to the same extent that Puritain practices did. On the island colonies Religion was simply that. A practice of faith that could be used to determine if one’s actions were morally acceptable. Those living on the island colonies used this to their advantage by ensuring that their actions could be deemed acceptable through Christian ideals. They were even able to justify enslavement of people based on the fact that they could deny them the ability to convert to Christianity. Thus, it is clear that religion played an enormous part in setting the foundations for social hierarchy and secular order in each British colony in the Americas.

To reach a clearer understanding of the significance of each of these documents, please click on any of the images above. Our descriptions situate each text within the larger theme of religion in the English colonies.

Further Reading:

The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson: Puritans Divided, by Michael P. Winship

Anne Orthwood's Bastart: Sex and Law in Early Virginia, by John Ruston Pagan