Backlash to the Mascot's Removal

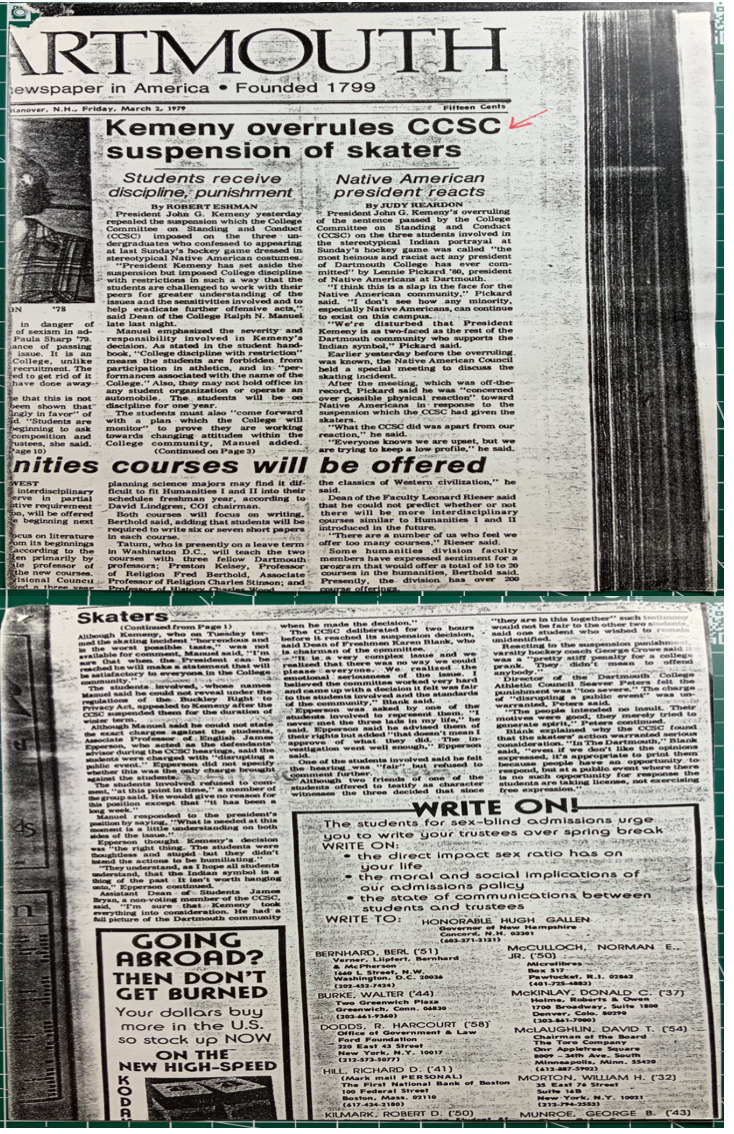

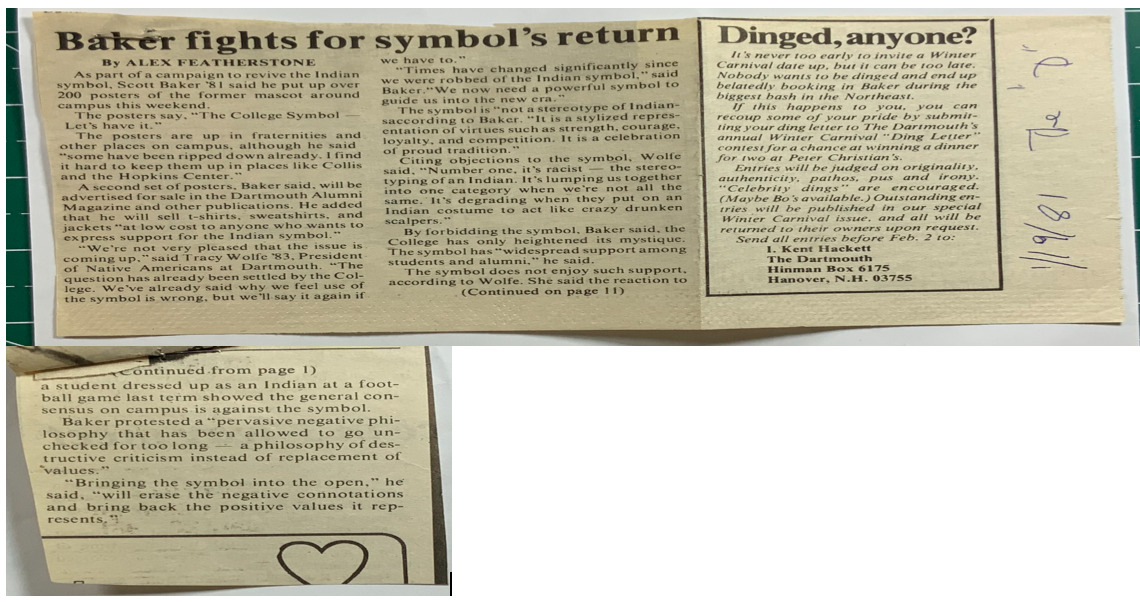

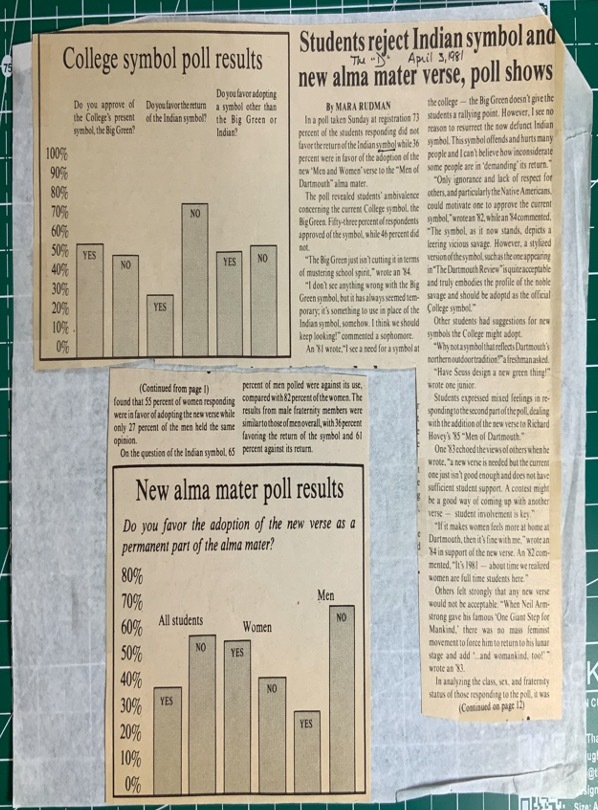

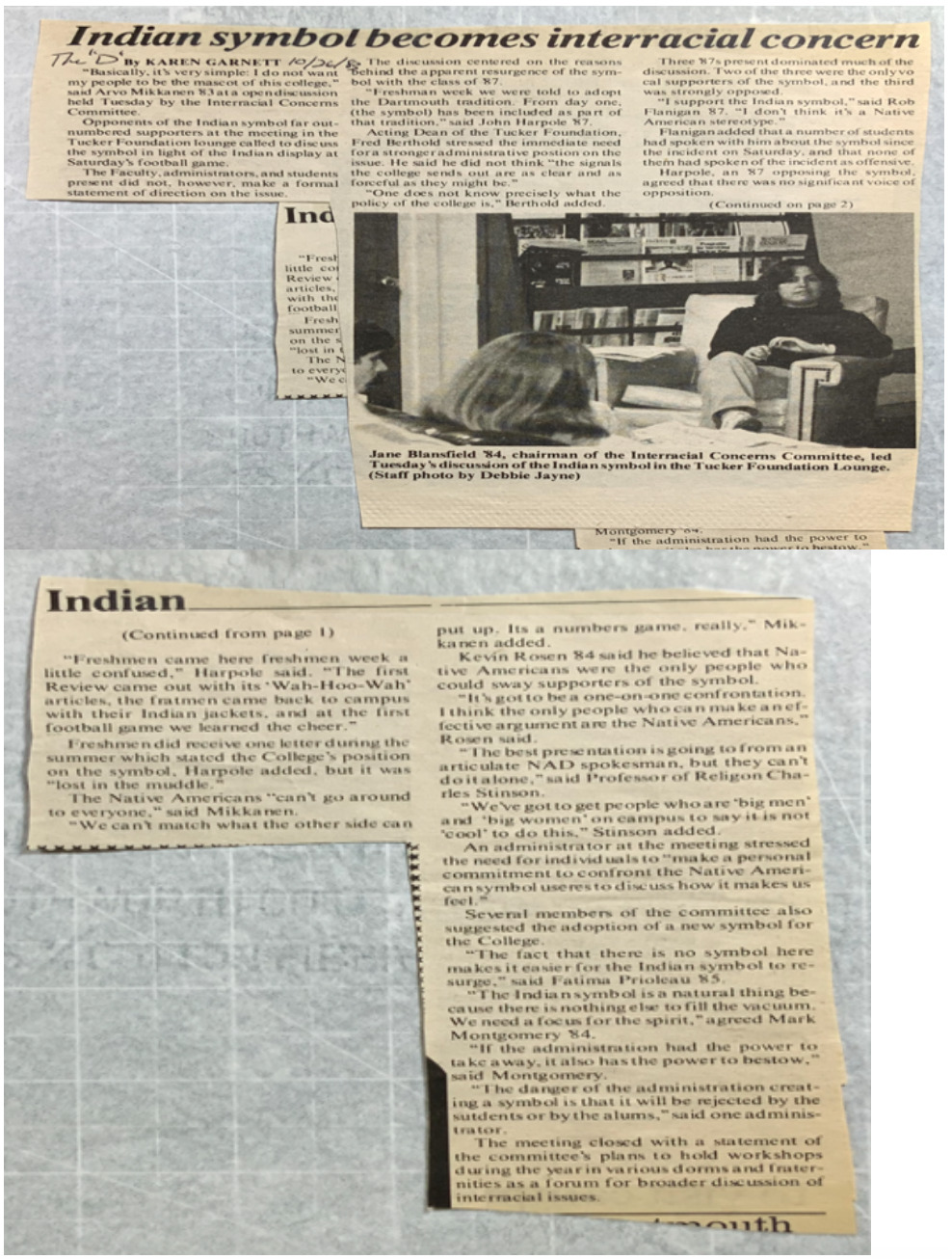

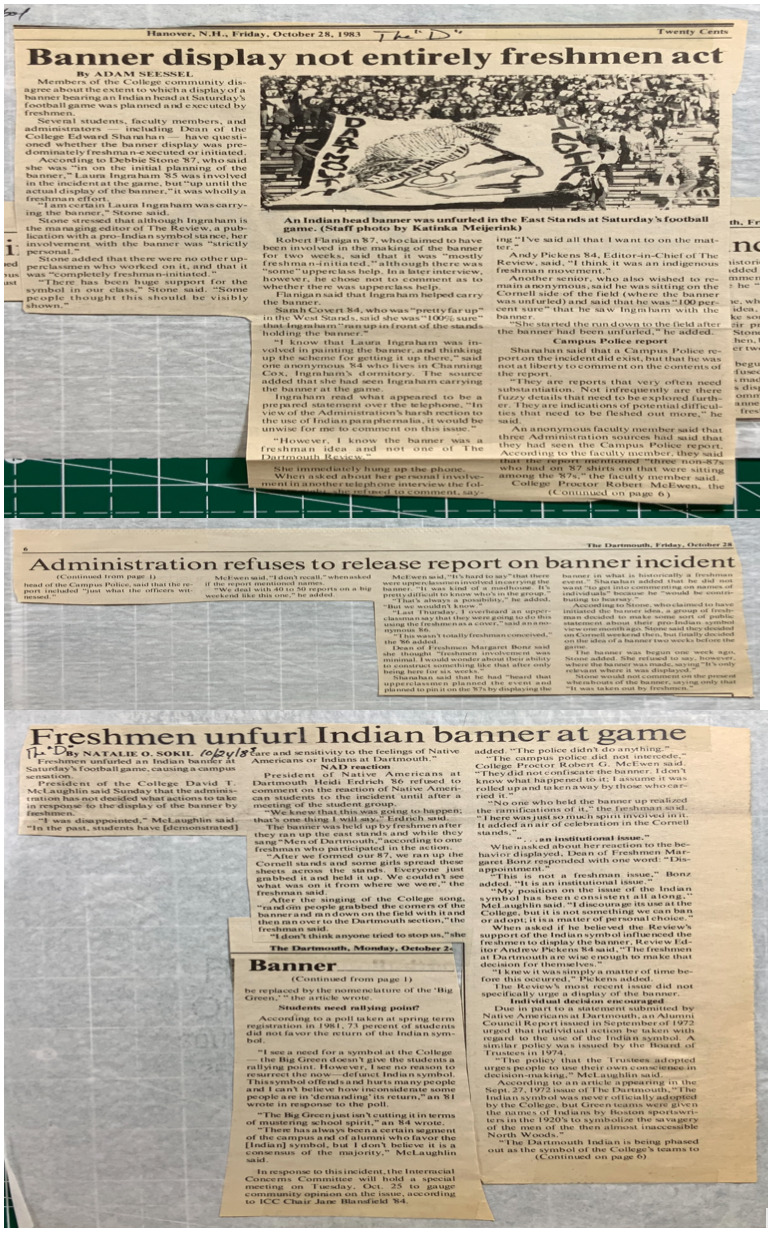

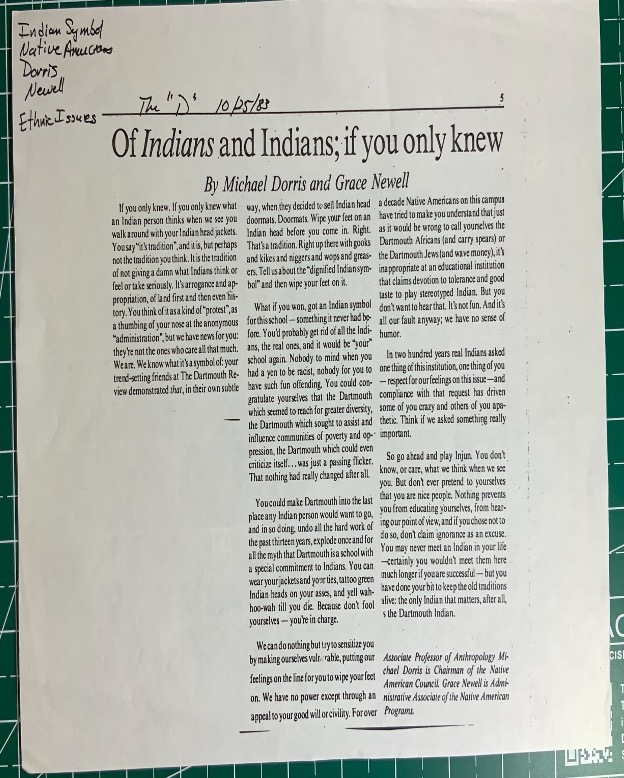

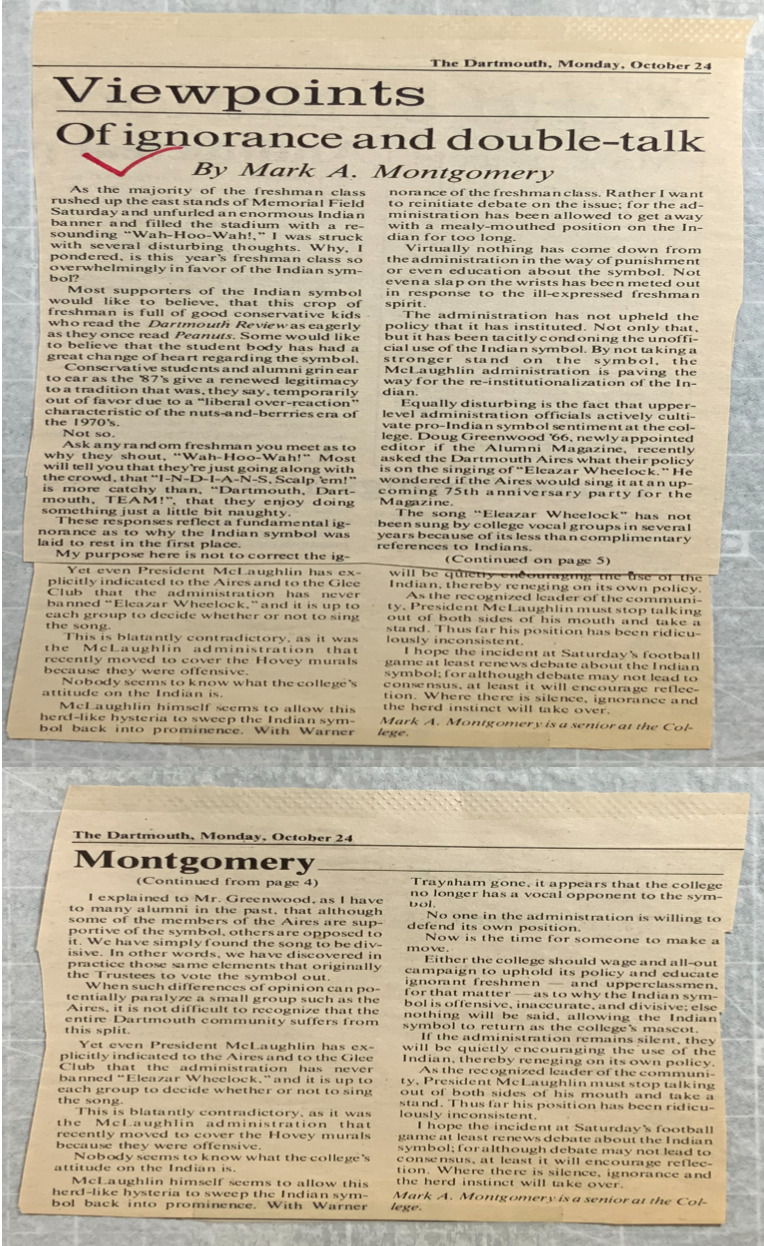

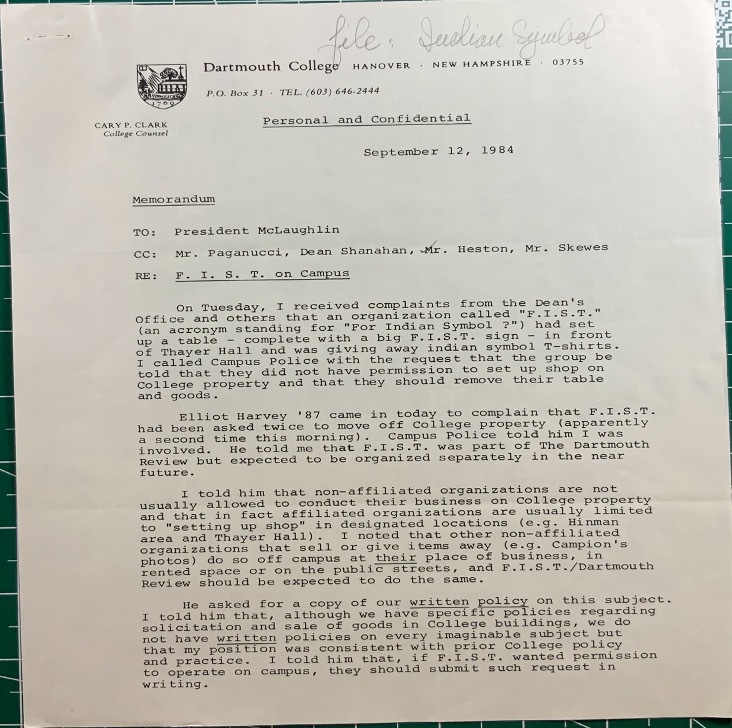

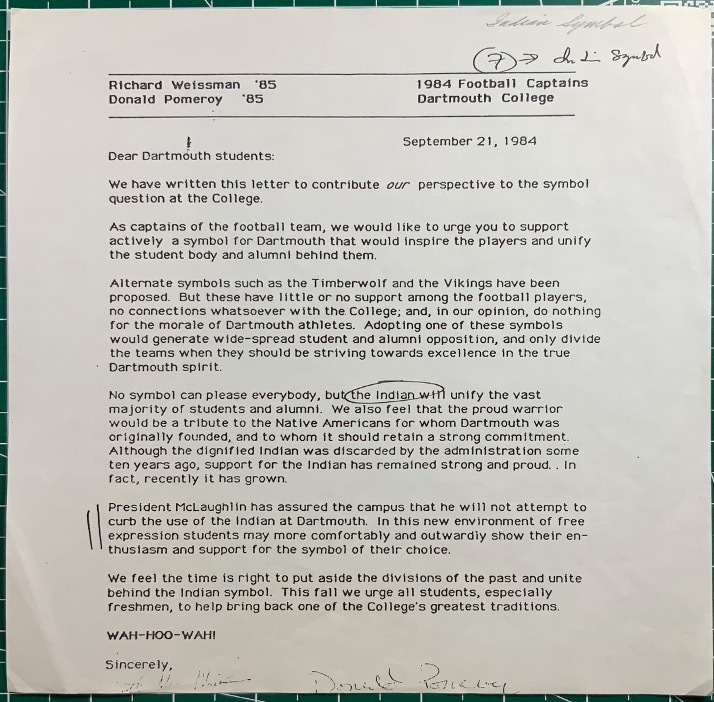

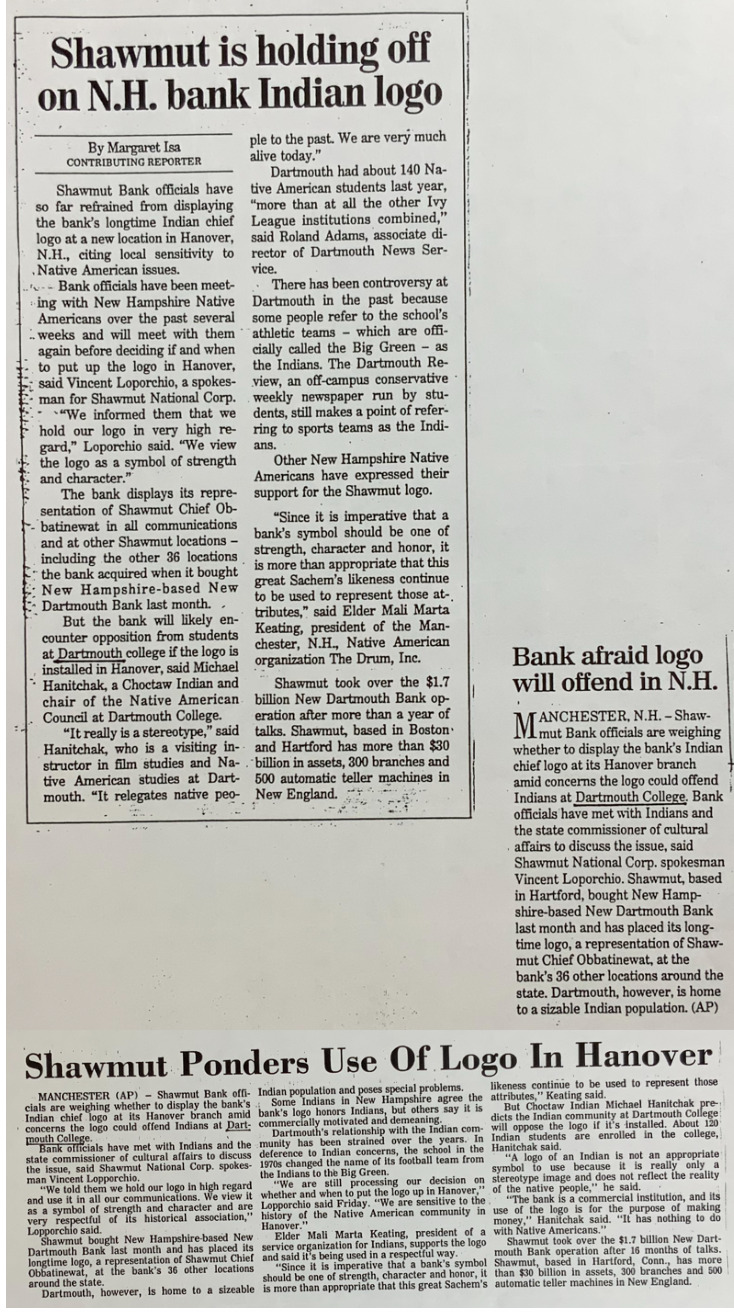

After the Indian mascot was removed in 1974, there were several periods in which support for returning the mascot to Dartmouth resurfaced. Support for the Indian symbol and mascot came from alumni, and on campus it was particularly strong among sports teams, conservative students (particularly members of the Dartmouth Review), and members of the freshman class during the fall of 1983, who carried out multiple campaigns for the Indian symbol’s return. Though it appears that, even at the height of student support for the Indian mascot after its removal, the supporting voices were far outnumbered by those who opposed the mascot, the students who wished to return the mascot to campus were particularly vociferous. They created enough campus strife in the early 1980s that the faculty canceled classes for a day in order to hold conversations about racism in the Dartmouth community. These issues exemplify the reality that, although the inclusion of marginalized voices is an important step towards reducing formal inequalities, it does not by itself eradicate the sources of those inequalities. Furthermore, they show that a relatively small number of people who loudly expressed their support for the mascot were able to polarize the campus debate. Overall, this story further highlights the ephemeral nature of equality, making clear that it must continually be pursued in order for it to be maintained.