The Mascot's Removal

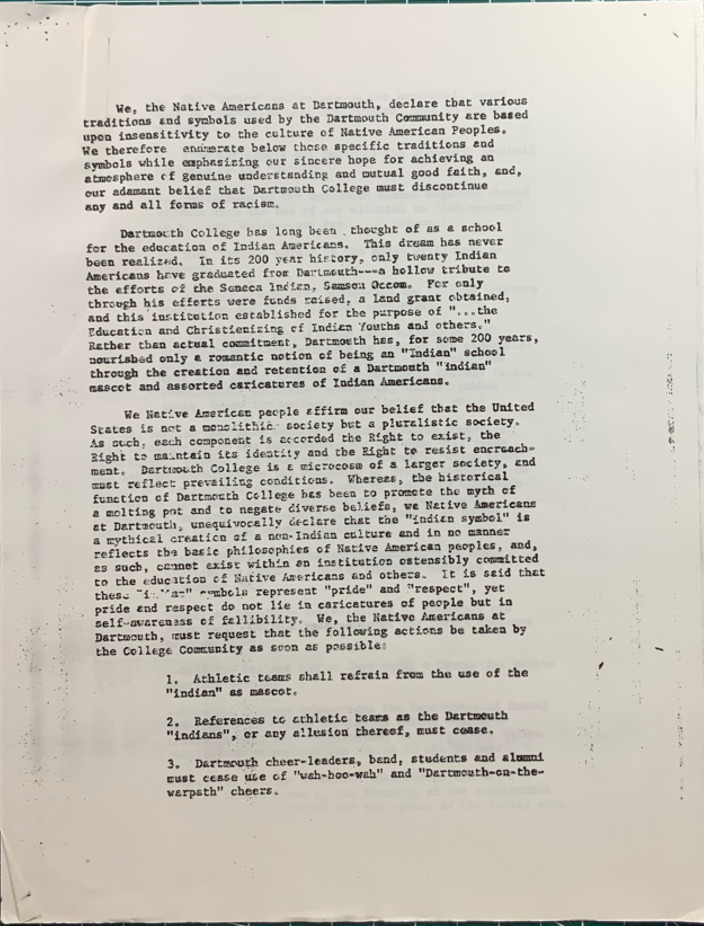

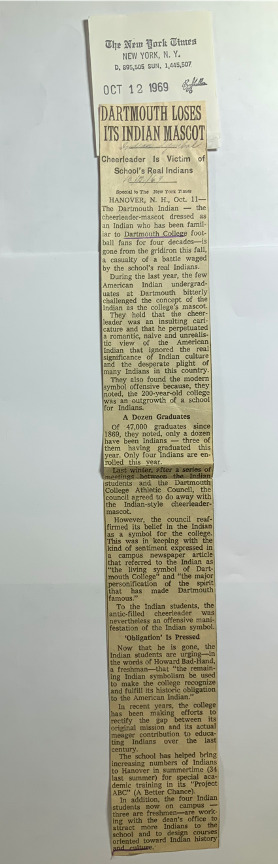

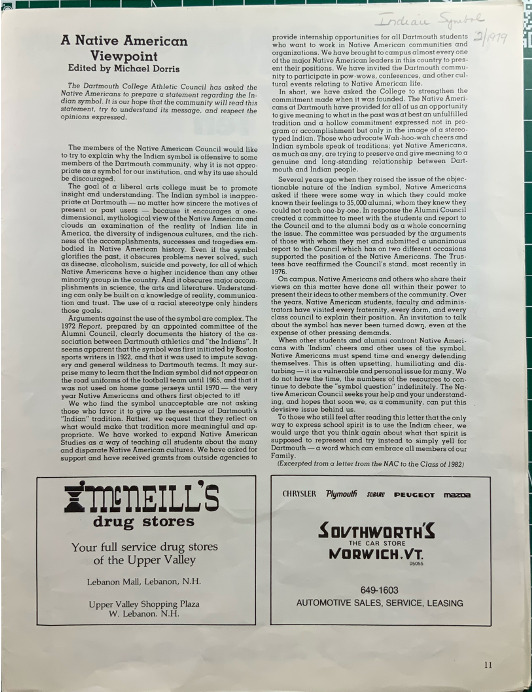

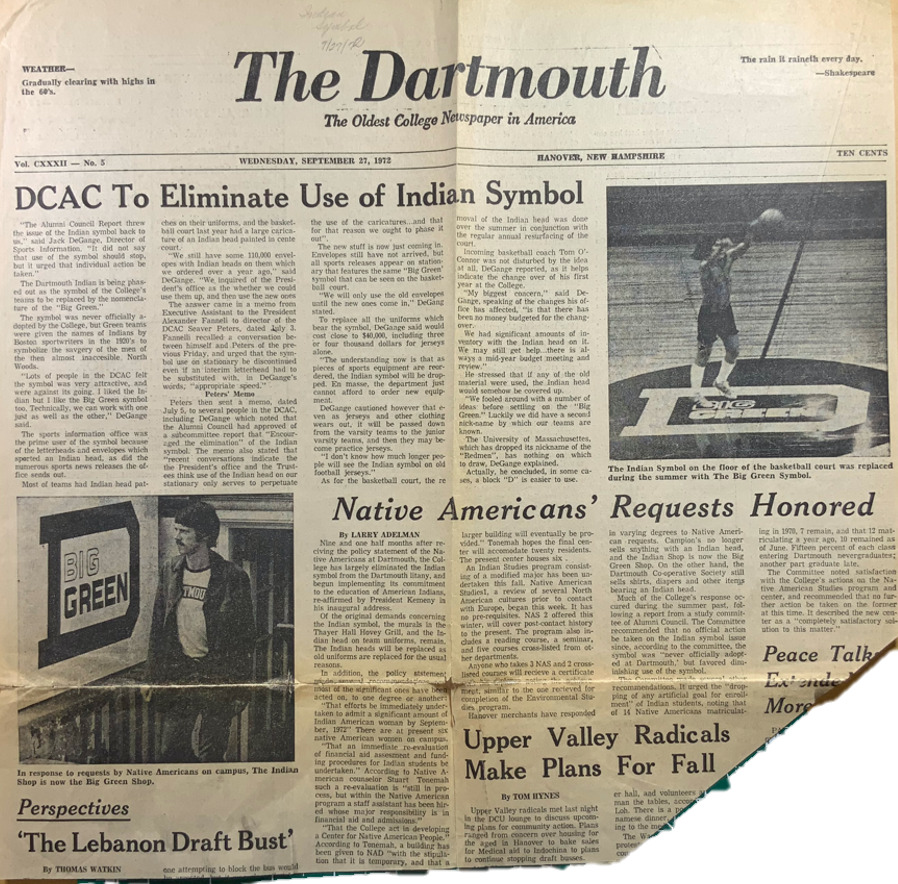

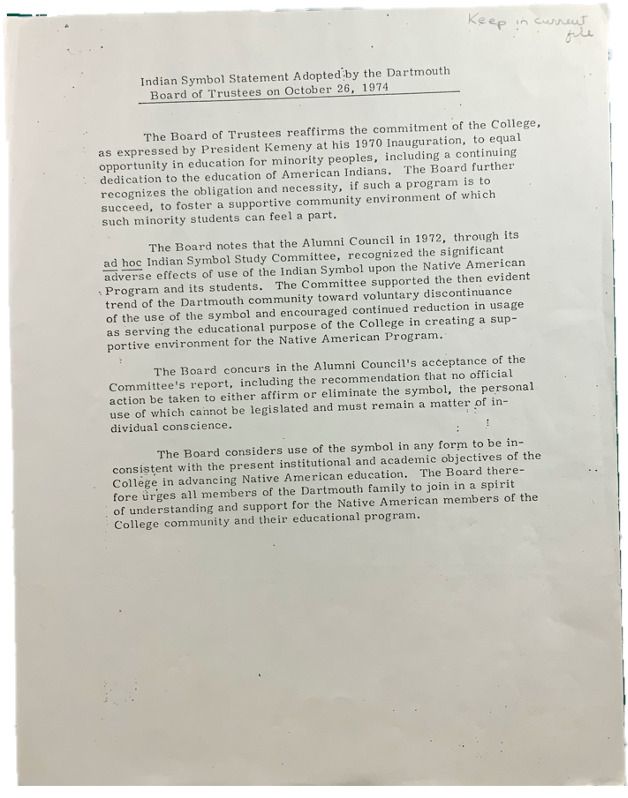

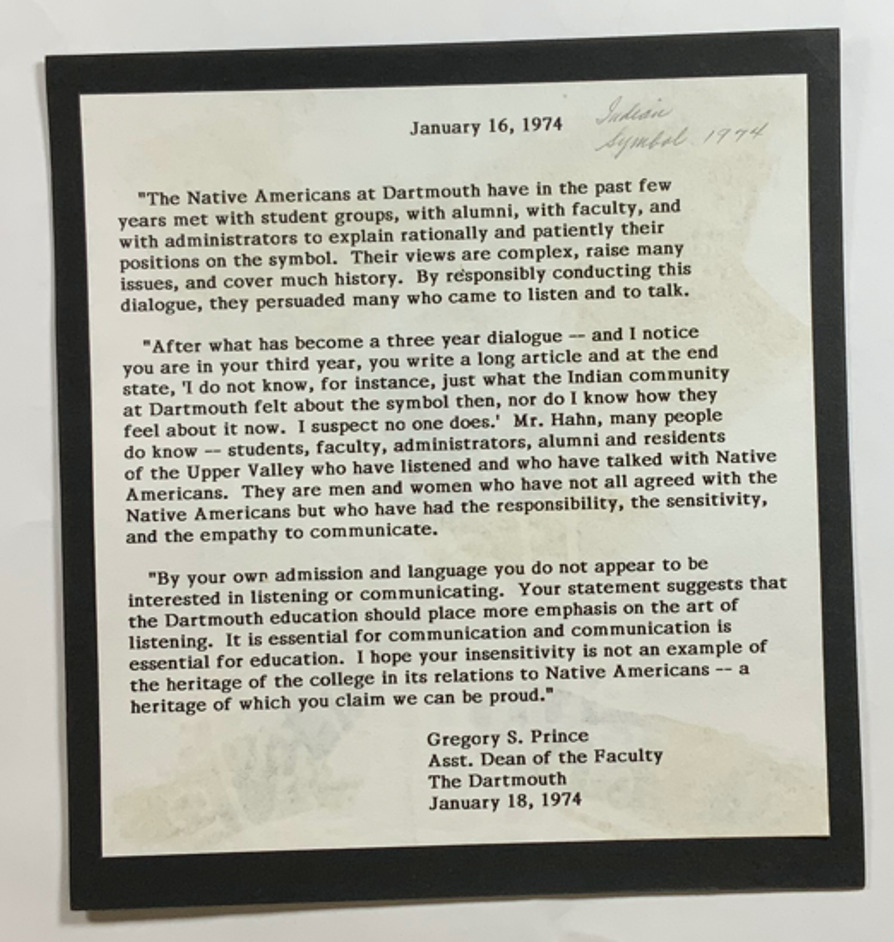

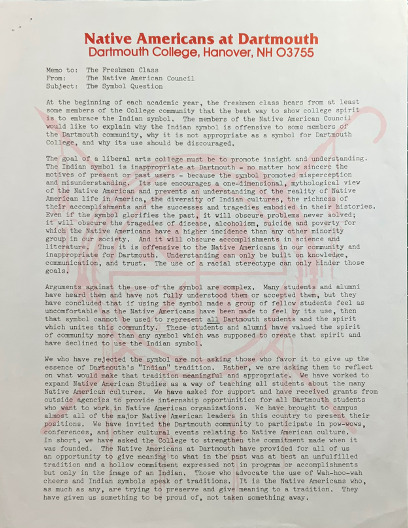

For most of Dartmouth’s history, minority voices were excluded from the student body. Without Native American students to defend their complex heritage, the Indian symbol caught on as the unofficial icon of the College and its sports teams. However, in the second half of the twentieth century, Dartmouth refocused on admitting Native American students and fulfilling its foundational promise to educate them. Now fully integrated into campus, Native American students finally had a clear voice, and as a part of the Dartmouth community, they were heard by many administrators, students, and alumni. The students effectively communicated how the use of such caricatures as the Indian symbol undermined their Dartmouth experience, while making clear the pain and discomfort they felt as fellow students shouted the “Wah-Hoo-Wah” chant at them. Demanding equal treatment, they fought to be free from the insults and mockery they experienced on account of their race and culture. White fellow students and alumni frequently claimed that their invocation of the Indian symbol was merely the glorification of a vaunted Dartmouth tradition, and not ill-intentioned. But Native American students succeeded in the end in convincing many, though not all, that the symbol’s continued use misrepresented, and denigrated, Native American history and culture.