Practical Obedience: Epidemic Intersections of Religion and Public Policy

“Do Thou, O Lord, ward off from us the farther inroads of that desolating plague, which, in its mysterious progress over the face of the earth, has made such fearful ravages among the families of other lands. Hitherto, O God, Thou hast dealt mildly and mercifully with the city of our habitation. Do Thou pour out the Spirit of grace and supplication upon its inhabitants”

From “The efficacy of prayer : a sermon preached at St. George's Church, Edinburgh, on Thursday, March 22, 1832, being the day appointed for the national fast on account of the prevalence of cholera.”

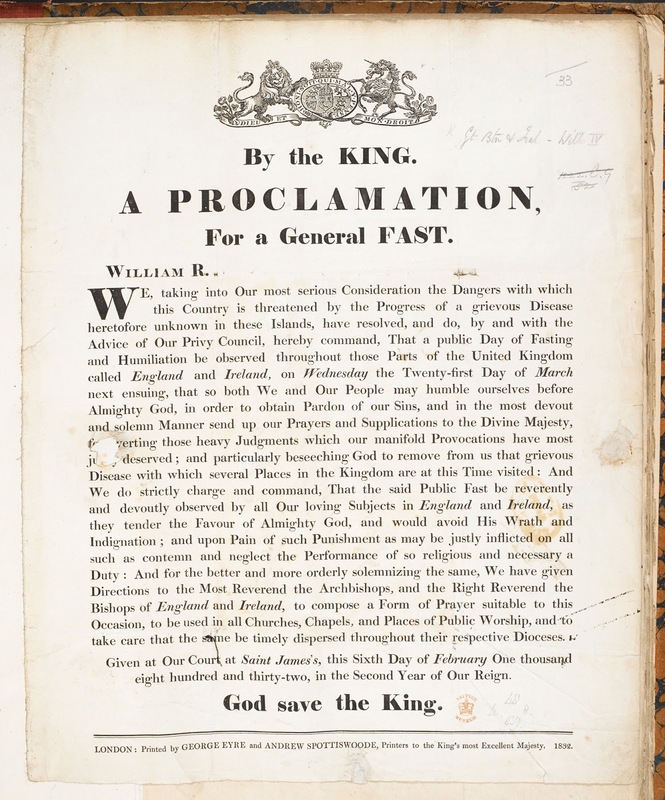

On February 22, 2021, President Biden issued a presidential proclamation that ordered that flags be flown at half-staff for five days to mourn Americans lost to the COVID-19 pandemic. Attired in black, head bowed, surrounded by 500 illuminated candles, the president led the nation in a ceremony grieving half-a-million lives. Less than two centuries ago, across the Atlantic Ocean, the King of England decreed a national day of fasting on March 21, 1832 in response to a similar pandemic, and one that was no less deadly—cholera.

Across England, Ireland, and Scotland, churches heeded the national proclamation and mobilized their congregations in a day of fasting. It is unclear how the people reasoned that abstinence from food and drink would resolve the pandemic, or ward the illness from their towns. Nonetheless, following Christian and Jewish tradition, it is likely that the act of fasting held greater symbolic than practical significance; it served to both unify the country and humble the people in the eyes of God as they prayed for deliverance from the pestilence. This approach transcended geographic borders; even in the United States, congregations viewed fasting as a “time for humiliation and prayer”, a practice of self-reflection that would cause people to dispose of impure thoughts and sinful behaviors (Barrett, 5).

In one such chapel, Thomas Chalmers –a pastor at St. George’s Church in Edinburgh– led parishioners in a prayer to “ward off from [them] the farther inroads of...desolating plague” (Chalmers, 1). Chalmers notes that society at large believes in a natural course of nature that neglects the ability of divine power to alter the natural progression of events. Despite our faculties of observation which “ [carry] us a certain way along the chain of causes and effects”, there are supernatural phenomena that surpass our understanding (Chalmers, 7). Clearly, members of the church perceived a limit to the explanatory power of scientific reasoning and hinted at variables that were beyond human control, such as divine will and the influence of greater powers.

Given the emphasis placed on divinity, it may be tempting to classify Chalmers and his followers as religious fanatics who solely depended on God’s favor to guard them from disease and pestilence. However, Chalmers shifted away from this single-minded focus by imbuing his message with a healthy dose of pragmatism and common sense. He advised the congregation to refrain from wantonly exposing themselves to the virus’ influence or to cast away their “means of security”(Chalmers, 21). Furthermore, he cautioned them from dwelling in the extremities of both faith and science while neglecting the other since casting away prayer creates the infidel and casting away practice creates the fanatic (Chalmers, 21).

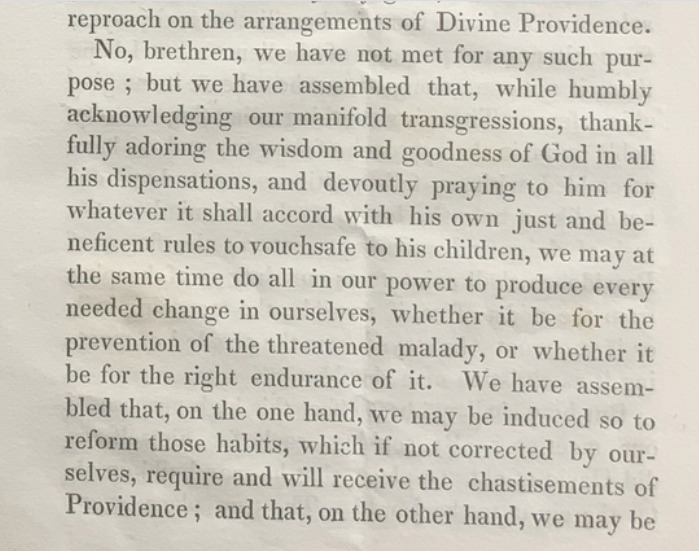

When the pandemic had made its way into the United States in 1832, it coincided with the Second Great Awakening –a period of heightened religious fervor– so that populations living in antebellum America interpreted the epidemic through the lens of faith (Jortner, 239). During this period of time, Methodist church membership had almost tripled while the [U.S.] population had not yet doubled (Jortner, 239). The consensus among religious figures, such as Samuel Barrett – minister of the twelfth congregational church in Boston– was that the arrival of cholera to North American was a “divinely appointed course of nature” (Barrett 5). Though Barrett’s hometown of Boston had been spared by the illness, he nonetheless encouraged the audience to repent their sins and “reform those habits” which if not corrected individually “will receive the chastisements of Providence”(Barrett, 5).

In the time of cholera, the Church, as an institutional power, united communities through organized prayer and fasting and provided clarity when parishioners struggled to rationalize this phenomenon that seemed to them like the mighty judgement of God. A critical takeaway is that the pandemic fostered societal cohesion; it brought people up out of spaces of confusion and despair into communal environments where they were advised on how to respond to the approaching disease. Collectively, parishioners absorbed the teachings of the Church and engaged in fasting and prayer, exhibiting their unwavering belief in that long-awaited day of deliverance from the disease. Similarly, in the modern era of COVID-19, when the recurring narrative forwarded by the media is one of grief, unbelievable loss, and societal trauma, people find reassurance in the message of resilience and unity emanating from our nation’s capital.