Plucked Chickens and Plague Water: Traditional and Unconventional Remedies

Familiar, traditional plant remedies as well as unconventional treatment ideas provided a coping mechanism for civilians as they grappled with rationalizing the plague’s baffling symptoms and devastating effects.

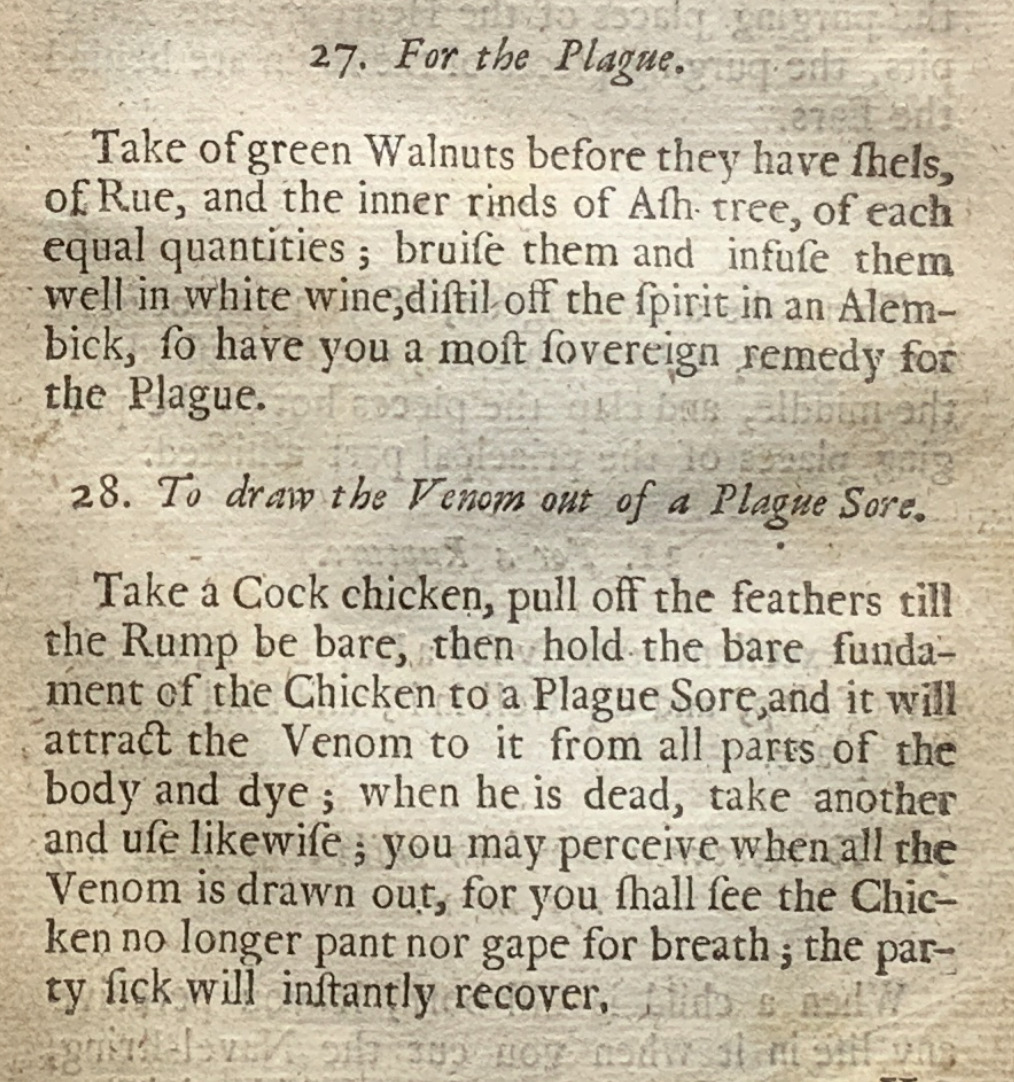

Culpeper's School of Physick"hold the bare fundament of the Chicken to a Plague Sore, and it will attract the Venom to it from all parts of the body and dye"

Herbalism, the employment of plant material to prevent and treat illness, had been a practice used quite some time before the emergence of the Plague, but the solutions offered to the plague were particularly specific and inventive. Nicholas Culpeper, a medical herbalist, preserved the tradition of orally transmitted superstitions and folk uses of plant medicines. As shown in the quote above, Culpeper mentions a method that differs from the more traditional method that appears above it on the page with recognizable ingredients such as rinds of the Ash tree and white wine. His second remedy involves sticking a bare chicken onto a person's plague sore, thought to transfer the poisonous matter from the human victim to the plucked animal.

Culpeper’s distinctive remedies display how civilians were trying to use the remedies to make sense of the disease and what harm it was causing. New unknowns emerged in different symptoms of the plague, which can be shown in the interpretation of plague sores. Culpeper tried to reason with the concept of infectious matter within plague sores, describing it as a venom and thinking it would make sense for venom to be transferred from one body to another, like that of the chicken. Since the concept of this poisonous matter contained in sores was so foreign to these civilians, more outrageous cures seemed to make sense and contain the same level of novelty as the disease itself.

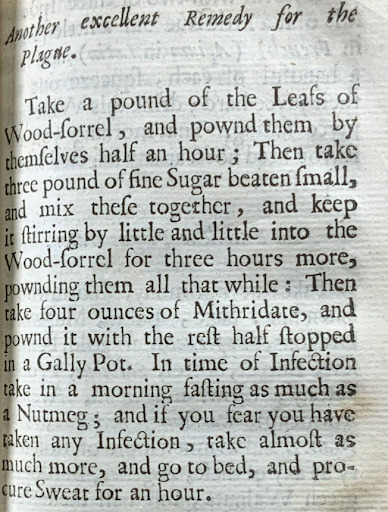

Alongside imaginative remedies and interpretations of symptoms, intricate details of remedies using familiar plants seemed to validate knowledge and trust in them due to their specificity. Kenelm Digby, Chancellor to the Queen Henrietta Maria, also collected recipes to cure many diseases such as the plague. By following precise methods and taking these remedies, people could feel calm and safe from “fear you have taken any infection”. In a time when people knew nothing, having instructions to follow strictly gave people something to count on. This is shown in Digby’s interpretations of remedies of the plague, which include pounding native herbs for a set amount of time or sitting in bed laying in sweat, as shown in the quotation below. Civilians were used to seeing or using ingredients like nutmeg, wood-sorrel, and sugar and could use appliances already in their home to concoct their remedy, giving them more comfort and security rather than heightened anxiety in viewing a medical professional.

"In the time of infection take in a morning fasting as much as a Nutmeg; and if you fear you have taken any infection, take almost as much more, and go to bed, and procure Sweat for an hour"

Digby's Receipts in Physick and Chirurgery

Digby’s role as a chancellor to the queen perhaps also emphasizes the legitimacy of his claims and remedies in the eyes of the general public, and were thought of as advancing scientific knowledge and beliefs. Putting their trust in Digby’s detailed remedies, civilians could feel they had more control over the unnerving situation.

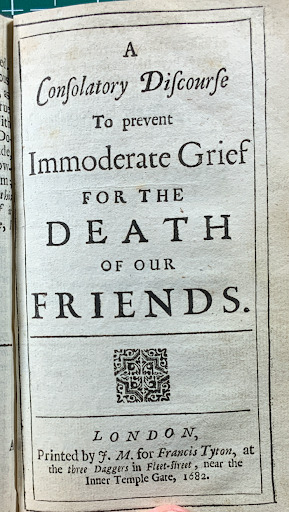

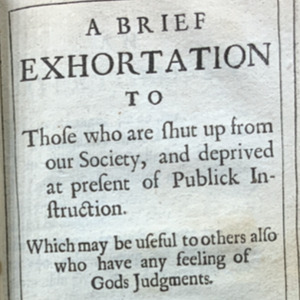

Besides particular remedies, other broad methods existed to cope with the high number of deaths in the community and make sense of the disease. These advertisements from 1682 show the impact of public unity and religion in offering coping mechanisms and guidance for those grieving their friends and family. This was a time for increased panic and reflection, especially concerning those who had feelings of the plague as a form of God’s judgement. By expressing their feelings and listening to sermons from religious figures, civilians could rationalize the terrible experiences they had faced and their thoughts. These gatherings were held at or near churches with members of clergy addressing civilians, revealing the influence of religion in reasoning and coping with death.

This idea of the influence of religion and coping plays into what civilians believed about the root of the plague and how they interpreted their fates and the death of their close friends and family. Coupled with emerging ideas in the scientific field, this resulted in various justifications for the plague, which are discussed on the following page.