The Poisonous, Noisome, Infectious, and Deadly Judgement of God: The Intersection of Science and Religion

While the people of 1665 London understand the signs and symptoms and the general infectiousness of the plague, scientists approach their findings with a gaze of a Christian religious foundation, causing many of their explanations to be due to the actions of God. Being satisfied with the plague as a punishment sent by God, the people of the time were not as inclined to search for the microbiological source of the disease

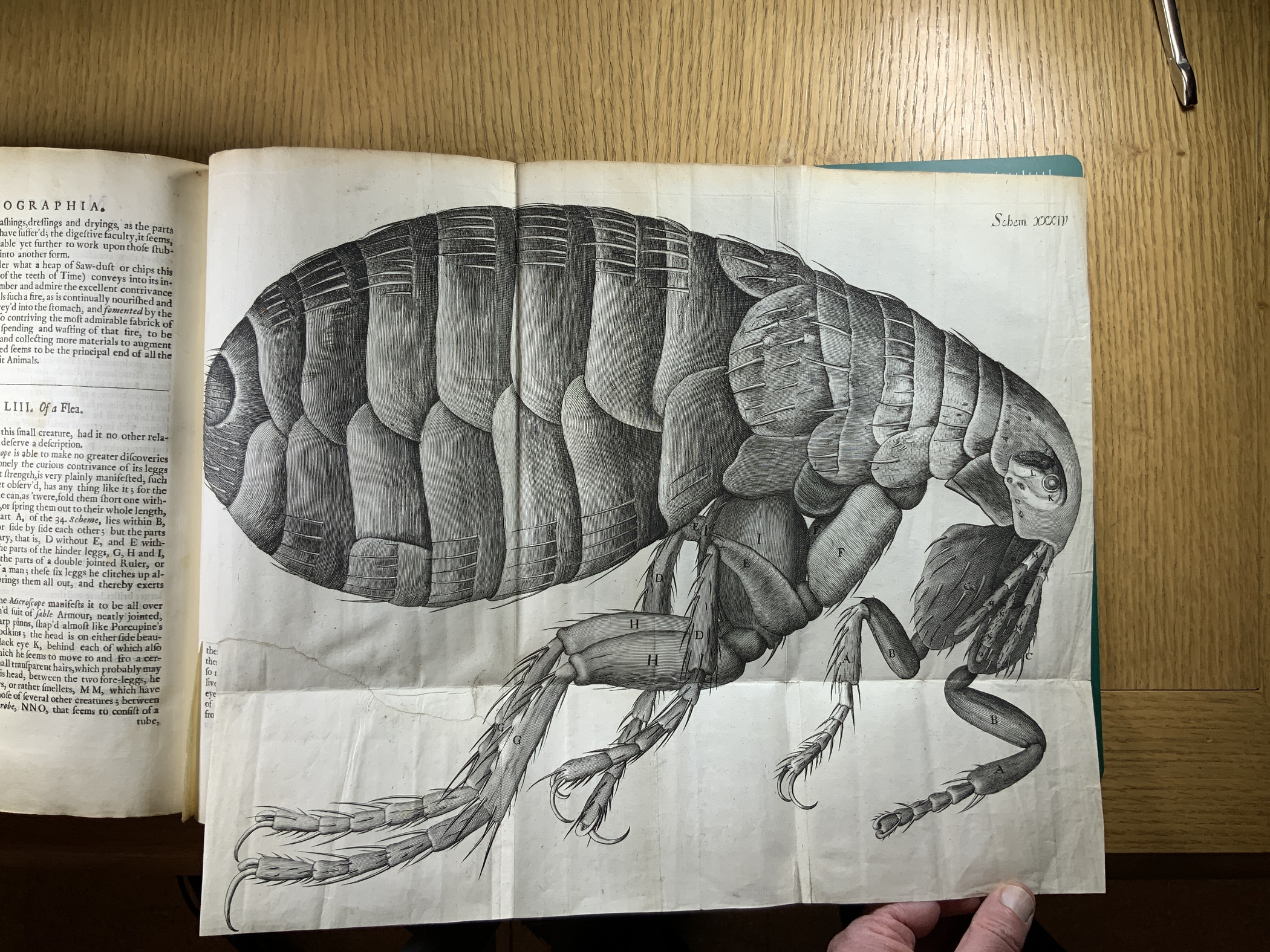

Robert Hooke (1635-1703) fondly describes how the strength and beauty of the Flea are so different from that of man and even if they had no effect on humans, it would still merit a description.

It is so interesting how fascinated scientists were with the flea, but how they had not made the connection between the small insect and the deadly plague that razed cities' populations.

We now know that the flea is the vector of the plague and by "exert[ing] his whole strength at once" that Hooke described is what allowed it to jump from host to host.

What will the flea of our generation of science be? What will future doctors and scientists look back upon and see an obvious truth that was unknown to us?

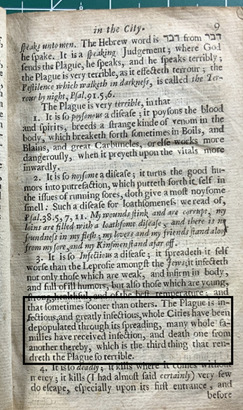

The plague was described to have four horrid qualities: how it is poisonous, noisome, infectious, and deadly. The unknown author of God's Terrible Voice in the City acknowledges how the science of the signs and symptoms of plague were understood by the public, however the root cause of the disease was given a religious explaination. The terrors brought by the plague were thought to be sent upon the unrighteous by God as a judgement and punishment.

The author argues that as God "hath no Mouth no Tongue", He cannot communicate in the same manner as man, and must speak in "extraordinary ways" through Judgements and Destructions. The plague is seen as just one of many modes of God's communication.

Looking at this source with a modern gaze, a plague sent by God does not align with the modern beliefs towards the causes of disease, however, most living in London in 1665 were Protestant or Puritan, both of which are forms of Christianity, and God was seen to be much more involved in the doings of the city.

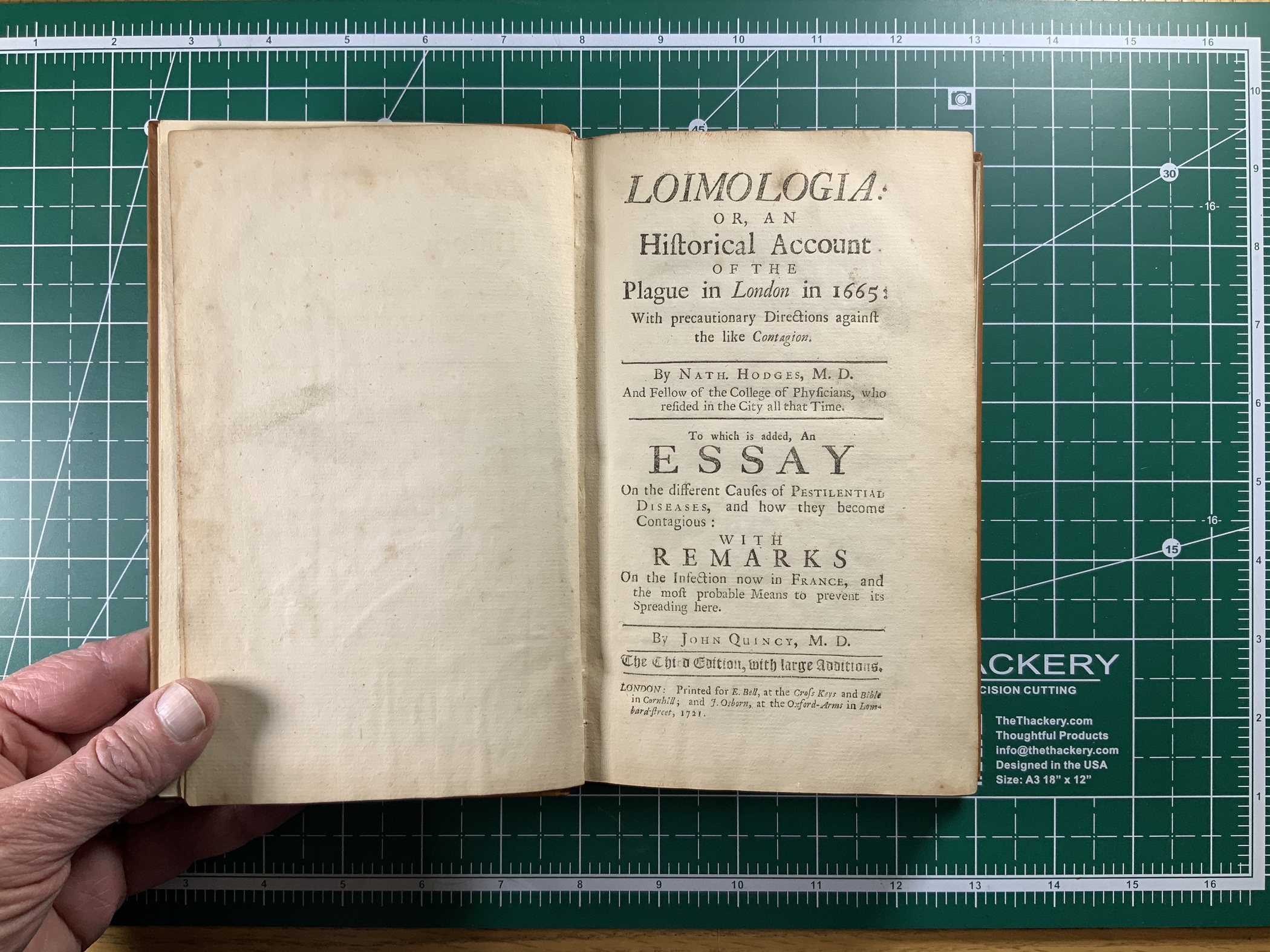

Having been published over 50 years after the Great Plague of 1665, the author of the added essay is rather critical of the past and claims that unlike those in 1665, contemporary (to 1721) scientists have the "right understanding of the Contagion". Furthering his critique, John Quincy claims that the people of the past were being misled by those who claim to be scientists, but rather are naturalists who attempt to treat all ailments with concoctions of the "inanimate Productions of Nature".

While it is easy to take the side of John Quincy and agree that Londoners in 1665 were misguided, it is more important to determine the root cause of the unpurposeful neglect towards the subject of scientific research. Soon after the reversion to a Protestant King on the British Throne, the plague ensued. Believing this was a judgement and punishment sent by God, scientific research of the disease was not encouraged by the state. Today, one of the first actions towards solving most global health issues is to set teams of researchers on the path to find treatments, cures, and preventative measures. This is just not what it was like at the time of the 1665. However, after the development of the microscope by Robert Hooke that same year, there was a boom in scientific research, leading to Antoni van Leeuwenhoek's discovery of bacteria in 1676. The knowledge of Yersinia pestis and the flea as a vector would not be discovered until the late 19th century by Alexandre Yersin and Jean-Paul Simond, respectively.

Scientists Mentioned