Smallpox's Tri-Continental Affair: 1700-1800s Transference of Knowledge

In the 1700s and 1800s, knowledge was as valuable a commodity as spices or tobacco, and it changed hands at a rapid pace. Europe’s thirst for new land and resources, manifested through exploration and colonization. Europeans sent ships far and wide to both acquire information and claim lands, peoples, and animals in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. However, during this era of mercantilism and colonial expansion, diseases that had previously been confined to their respective continents also began to travel the world, unwanted yet unavoidable.

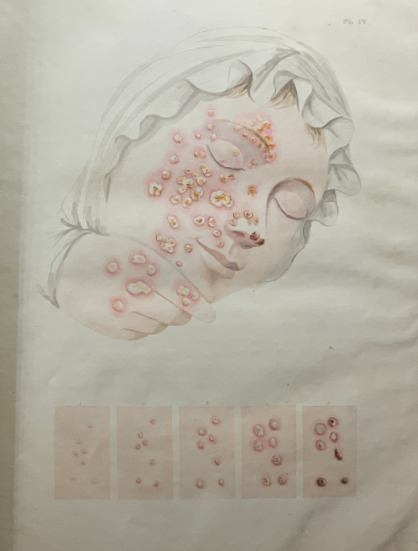

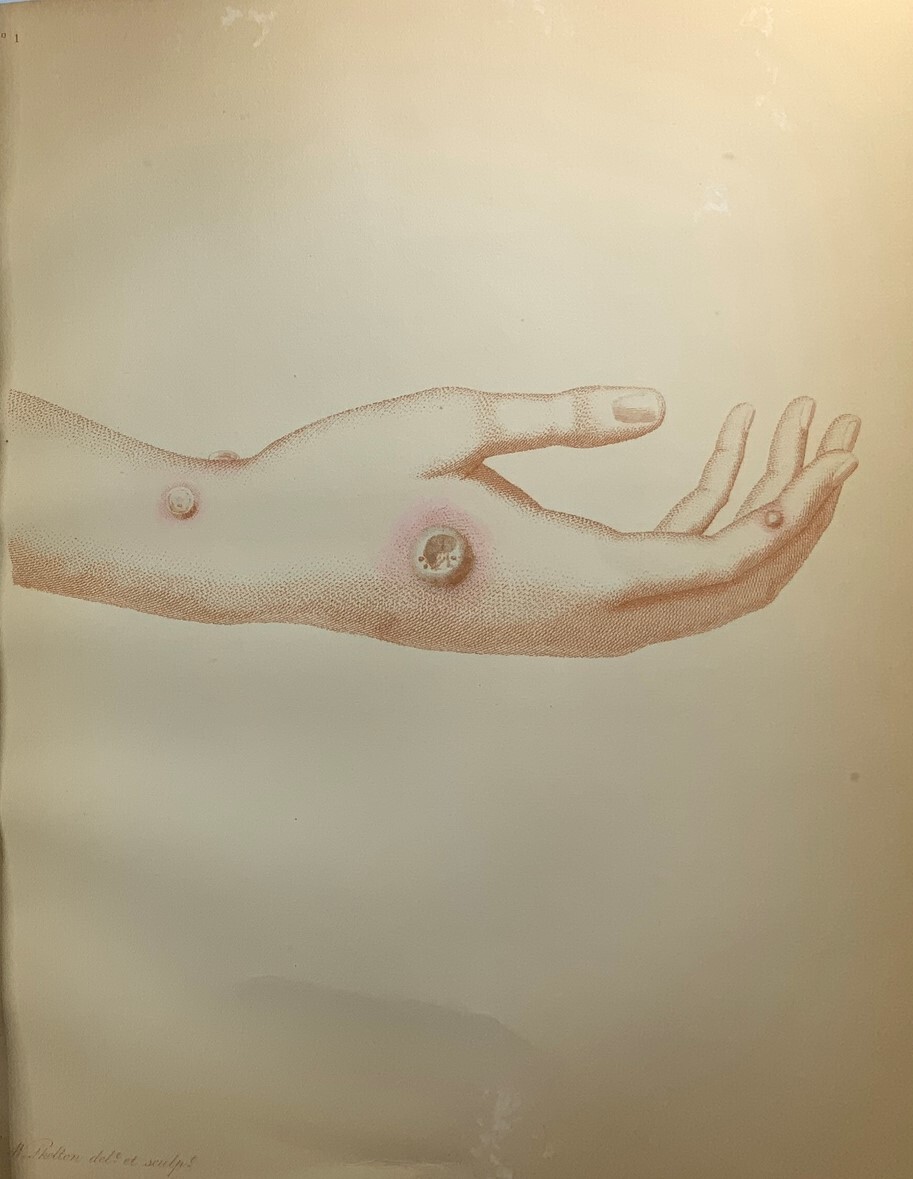

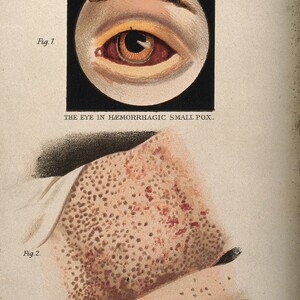

The Transatlantic Slave Trade also fueled this spread of disease: crowded, dingy slave-ships acted as fertile breeding grounds for smallpox, or the variola virus. Transcontinental spread of the disease claimed the lives of people across Europe, Africa, and the New England colonies, prompting a search for solutions to the itchy lesions and fevers characteristic of smallpox. Today, vaccines mitigate the risk of catching deadly viruses like smallpox, but in the late 1700s-1800s, treatments were only beginning to be developed.

Honing into three continents – Europe, Africa, and North America – provides a clear narrative about smallpox’s cultural journey. Characteristic of historical events, those in power wrote the script of smallpox’s destruction and after observing enslaved West Africans practice smallpox inoculation, Europeans immediately began to experiment on enslaved people themselves and eventually adopted this practice, burying the origins of this ingenious practice and taking credit. Still, integrating the inoculation method of transferring smallpox from a diseased individual to a healthy one into colonial life proved highly indicative of the morals and cultural norms during the time: religious pushback and strong public distrust significantly hindered the initial rollout of inoculation and, later, the development of a smallpox vaccine in North America.

As we look deeper into the cross-continental interactions between smallpox and the people it impacts, this exhibit tracks the ways that the manifestations of smallpox exceed its epidemiology by adopting cultural meaning beyond pure medicine. Though the science behind the incidence, spread, and attempts at eradication of smallpox through initial inoculation and later vaccination are well documented, this exhibit takes up the humanistic themes of power in knowledge, religion in medicine, and shifting cultural norms surrounding viruses as a mode of further understanding the impacts of this infectious disease.

While considering the mentioned power dynamics facilitated by racial hierarchies of the period, it is important to view this exhibit with the intent of smallpox education while understanding that some crucial knowledge may not be accurately credited to those who deserve proper recognition.

To view a breif overview of the exhibit, in the form of a timeline visit the page Smallpox Overview & Time Line, or navigate using the bellow buttons!