From Africa to Europe: Stolen Knowledge and Experimentation

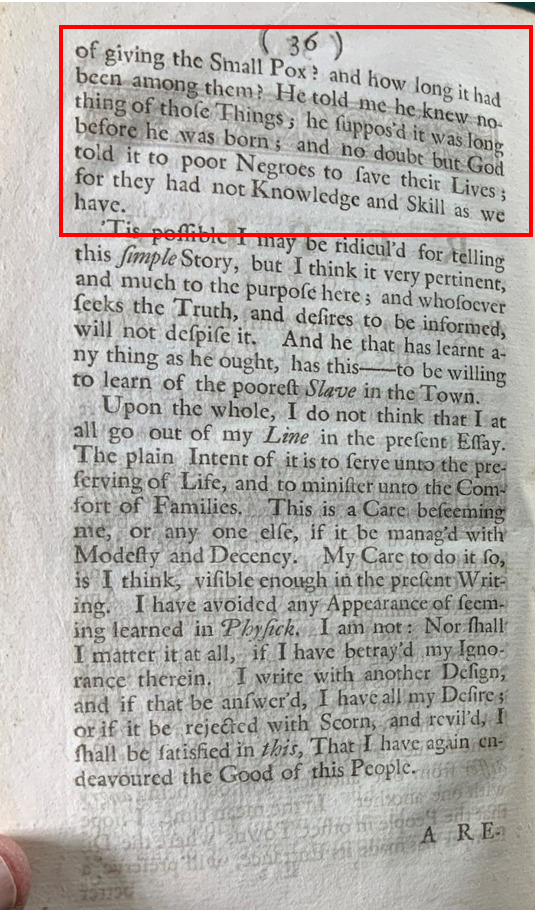

You might know the story of the smallpox vaccination from studying the development of the 13 colonies in a US history class. New England colonist and minister Cotton Mather successfully introduced inoculation during an outbreak in Boston in the 1720s, and within the decade Englishman Edward Jenner developed the more reliable smallpox vaccine - remarkable medical achievements, credited to these two pioneers. However, the roots of inoculation run deeper than this Eurocentric history: Asia, Africa, and parts of the Ottoman Empire all respectively utilized this ingenious, indigenous technique to treat smallpox as early as 1000 B.C.E*. Why then, has history once again ascribed this medical triumph to the Western world?

“...the Truth of this Relation [between inoculation and survival of smallpox] depending chiefly upon the Testimony of Negroes, I should think it worth while to consult some of our English traders to those parts, before we give entire Credit to it” (Coleman 1722).

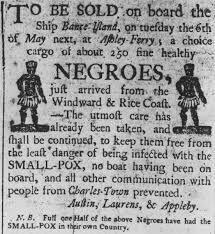

European traders sailed into Africa to assemble slave cargos and other African goods, not expecting to stumble upon a technique called inoculation to ward off smallpox. Coleman recounts the testimony of enslaved Africans that attested to this routine practice: unafflicted enslaved Africans bought in Guinea were sent to shore to be inoculated in order to fetch a better price later. By transferring smallpox material from an infected person to an unafflicted person, the reciever contracted a mild case of smallpox that also bestowed an immunity to smallpox. Traders recognized the benefits of transporting and selling inoculated enslaved people, as seen in the advertisement to the right. Yet the enslaver / enslaved person dynamic rears its head in a particularly pointed manner. Perspectives on race found their origins in the European Age of Exploration, as Europeans met countries populated with people whose appearances and cultures differed from their own. These collisions slowly spawned the concepts of race and hierarchy, nurtured by philosophers and scientists, and paved the road for slavery as an acceptable facet of society. As a result, despite prior ignorance, Coleman, an American colonist, dismisses the expertise and long-held experience of the Africans in his book about smallpox, preferring to defer to English authorities. Power controls the narrative, and as slave traders, Europeans were quick to test this novel technique of inoculation at their leisure, often at the expense of the less fortunate.

"Next Month [Mr. Maitland] perform'd the Operation on the only son of a learned Physician in London...he engrafted the Small Pox on six of the condemned Criminals at Newgate...[Dr. Boylston] first tryed the Experiment on two of his Slaves, and then upon his Son, a Child of about five or six Years old..." (Coleman 1722).

Experimentation, as documented by Coleman about Englishman Mr. Maitland and colonist Dr. Boylston, rapidly followed the “discovery” of inoculation with impetuous force. While there certainly were less restrictions on experimentation on human subjects in the 1700s, the disregard demonstrated by physicians and intellectuals once again illustrates the hierarchical constructs of their time. Just as enslaved people were considered less than human because of their skin color and geographic origins, criminals also faced punitive treatment beyond jail time because both groups were disposable and easily replaced. Enslaved Africans, criminals, and even children essentially became lab rats for the smallpox inoculation, and while its efficacy had already been proven in Africa, the intent behind their actions as well as desperation to find a solution speaks to their values regarding medicine and their subjects. The lack of autonomy united these human subjects, demonstrating the movement of inoculation from “materia medica” to a process embodying the hierarchical and cultural constructs of the 1700s regarding race, classism, and ethics.

“That in their Country grandy-many dye of the Small-Pox; But now they learn This Way: People take Juice of Small-Pox; and Cutty-skin, and Putt in a Drop; then by'nd by a little Sicky, sicky: then very few little things like Small-Pox: and nobody dy of it; and no body have Small-Pox any more…” (Cotton Mather, Boylston 1975)

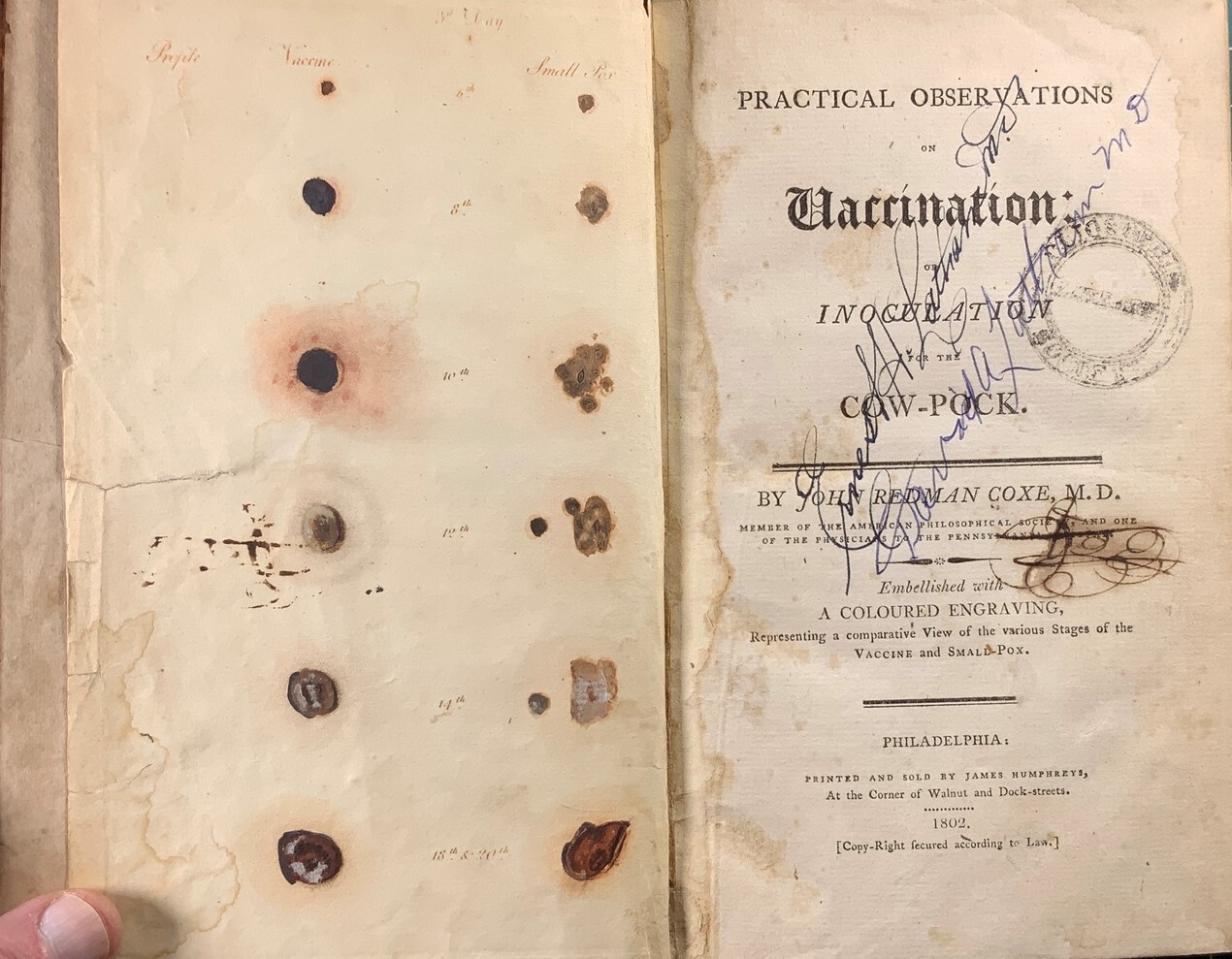

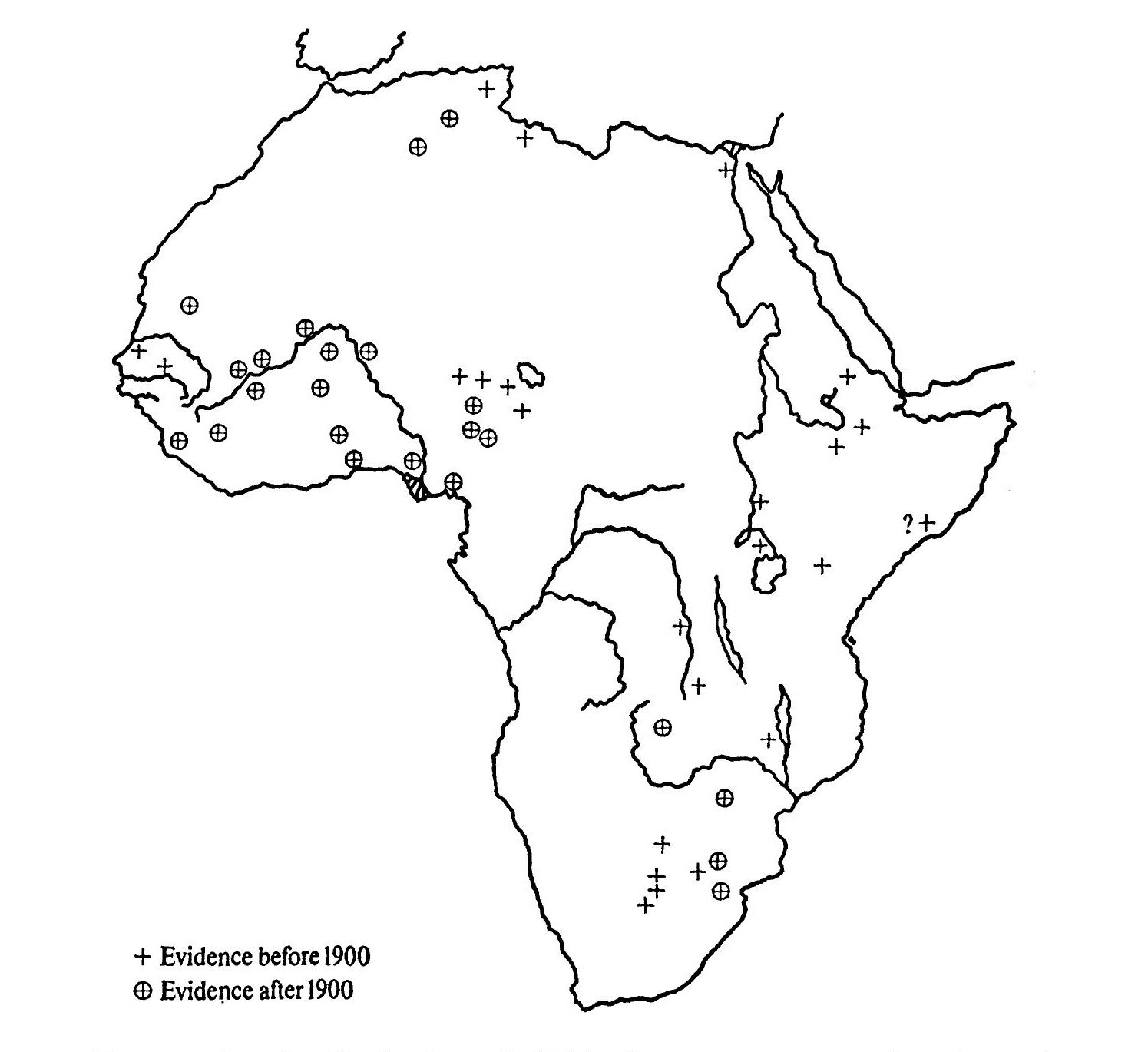

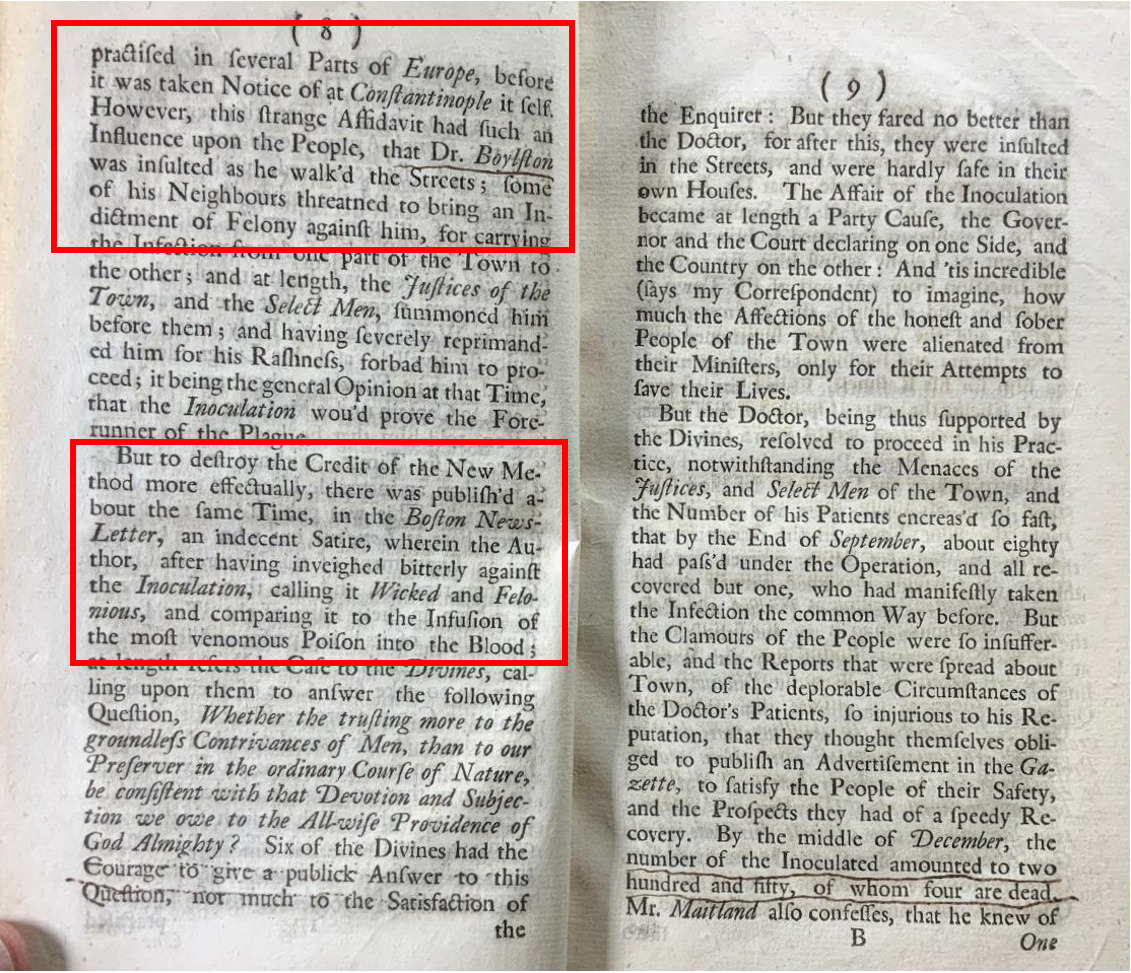

While detailed reports of inoculation in Africa are sparse, evidence suggests that the earliest known instances occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and were broadly used in Western and Central Sudan, Ethiopia and Southern Africa, as recorded by Europeans. Local practices differed widely in inoculation material and sites on the body as well.† Regarding the Europe-Africa transference of knowledge, colonist and minister Cotton Mather’s interactions with his slave Onesimus perfectly illustrates the emerging cultural life of inoculation. Though called “Guramantee” by Mather, Onesimus’ origins are undetermined, but he educated Mather on the practice of inoculation shortly after being enslaved. Mather then read accounts of inoculation practiced in England and Constantinople, enlisting the support of Dr. Zabdiel Boylston to spread the procedure in Boston. However, medicine, in all its empiricism, could not overcome the cultural and social body of power attributed to inoculation. The mere thought of relying on an African remedy, a slave-associated operation, disgusted the public and rallied them violently against Mather and Boylston. Eventually, high-ranking English figures embraced inoculation, and positive experimental results from Europe and America swayed public opinion based on cultural authority (discussed in the following pages of this exhibit), but initial reactions portray the beliefs of their time. Inoculation became a cultural technology wielded with the ultimate irony: though Europeans and colonists decried African knowledge as inferior, they claimed it as their own, twisting the narrative once again in their favor.

*This exhibit will focus on inoculation’s origins in Africa, not to ignore Asia and the Ottoman Empire but to allow a deeper exploration of tri-continental interactions of North America, Europe, and Africa.

† For a more detailed account of African inoculation practices, please read Herbert’s fascinating paper, Smallpox Inoculation in Africa, referenced the bibliography.