From Europe to New England Colonies: Religion and Doubts

In the eighteenth century, news of the varied effects of inoculation began to circulate between Europe and the North American colonies. In New England, connections to King George III were still prevalent, even among some Indigenous Americans, as will be highlighted soon. Loyalty to a 'United States' wasn't quite formulated yet. Both colonists’ and Native relationships to a far-off monarchy shaped how New Englanders consumed and digested knowledge, particularly in regard to medicine, religion, and politics. Loyalists, or supporters of the British Crown, received luxury goods from the 'mother country' like tea, processed goods, and news. Port networks between London and Boston established a basis for the spreading of medical news and procedures in New England, as described in Progress of the New Inoculation in America.

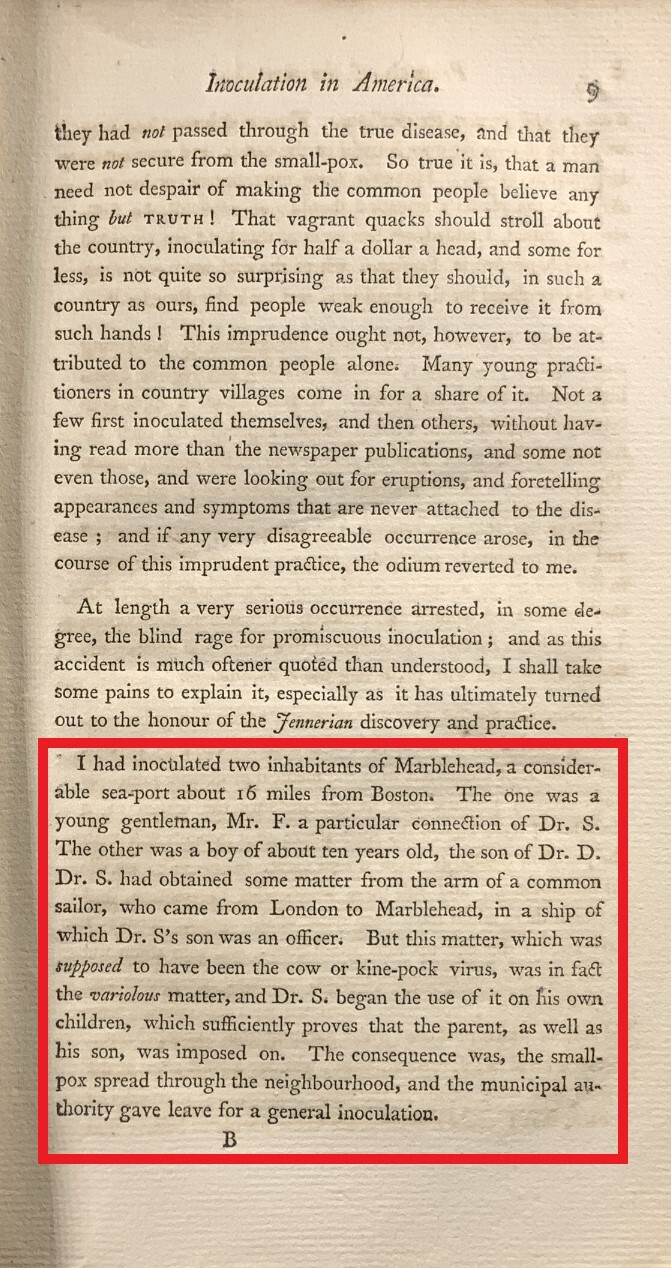

“I had inoculated two inhabitants of Marblehead, a considerable sea-port about 16 miles from Boston...a common sailor, who came from London to Marblehead in a ship” (Waterhouse 1802).

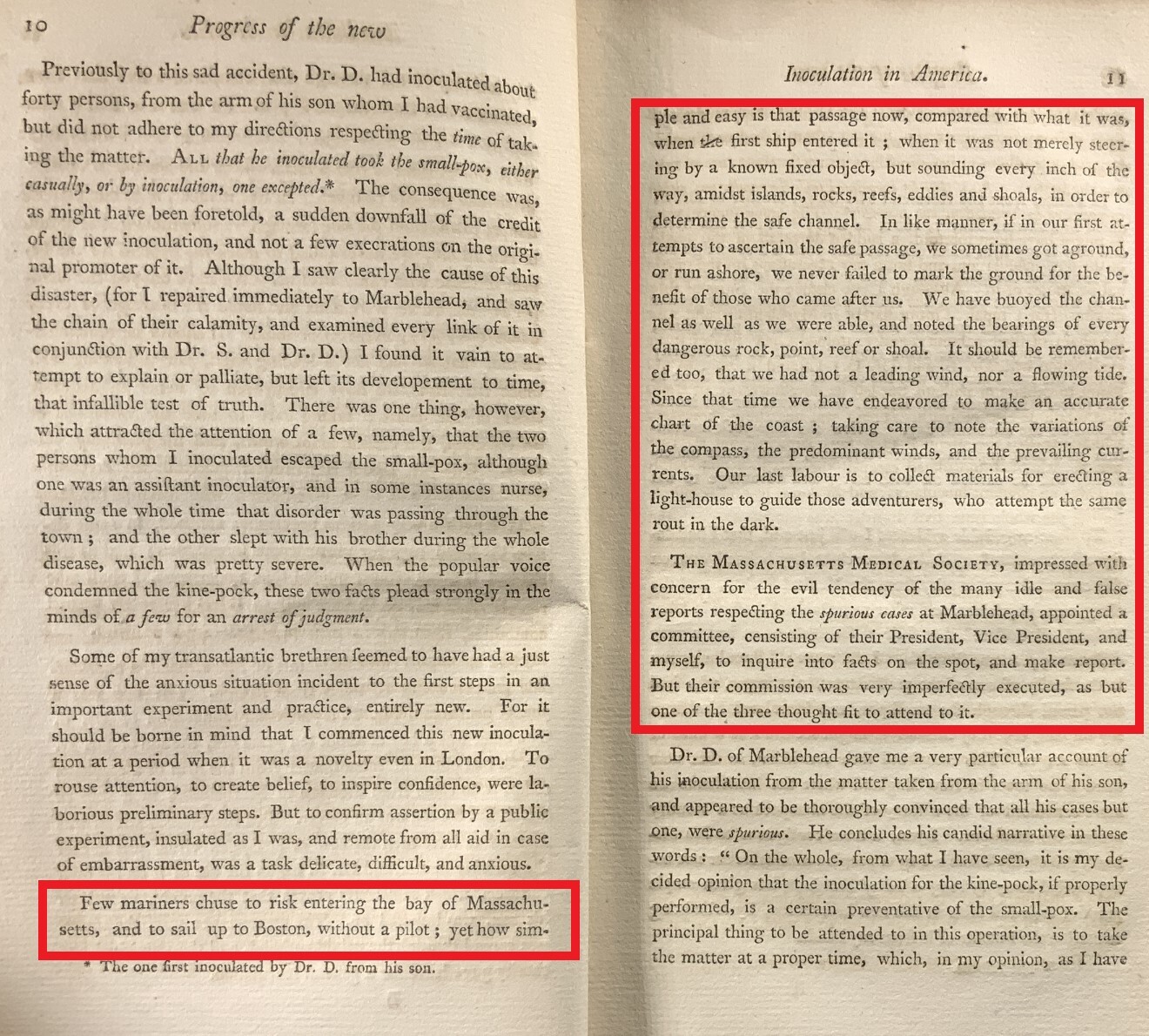

These well-established merchant pathways also created networks of shared knowledge, supported and guided by the question of the ‘best authority.’ New Englanders valued England’s systemic approach to medical inquiry over those based in the colonies or elsewhere. For example, Benjamin Waterhouse, educated in Great Britain, became a lead in the smallpox committee a part of the Massachusetts Medical Society.

“The Massachusetts Medical Society … appointed a committee, consisting of their President, Vice President, and myself, to inquire into the facts on the spot, and make report” (Waterhouse 1802).

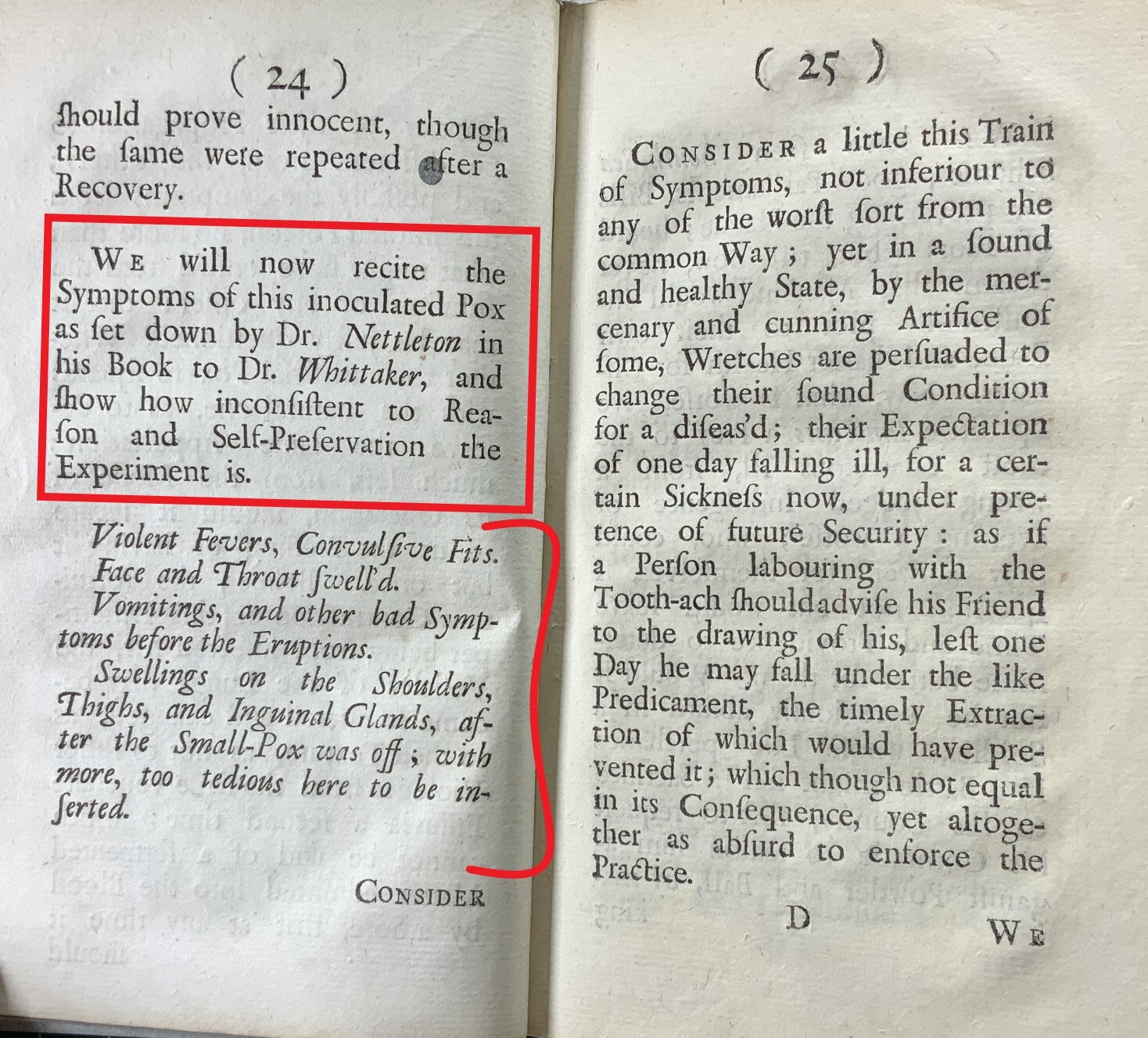

Further, in Reasons Against the Inoculating of the Small-Pox, there are repeated references to both personal anecdotes from English experiences and primary English literature from an English doctor. For New England colonists, trust was placed in English doctors, who were reputable because of their systemic approach to the treatment of, documentation of, and statistical recording of smallpox. This English process of receiving information, referencing other experts, and sharing new conclusions that captivated New Englanders is best evidenced by Reasons Against the Inoculating of the Small-Pox, where in building a case against inoculation, Surgeon Legard Sparham cites other English doctors’ accounts of its results.

“We will now recite the Symptoms of this inoculated Pox as set down by Dr. Nettleton in his Book to Dr. Whittaker, and show how inconsistent to Reason and Self-Preservation the Experiment is” (Sparham 1722).

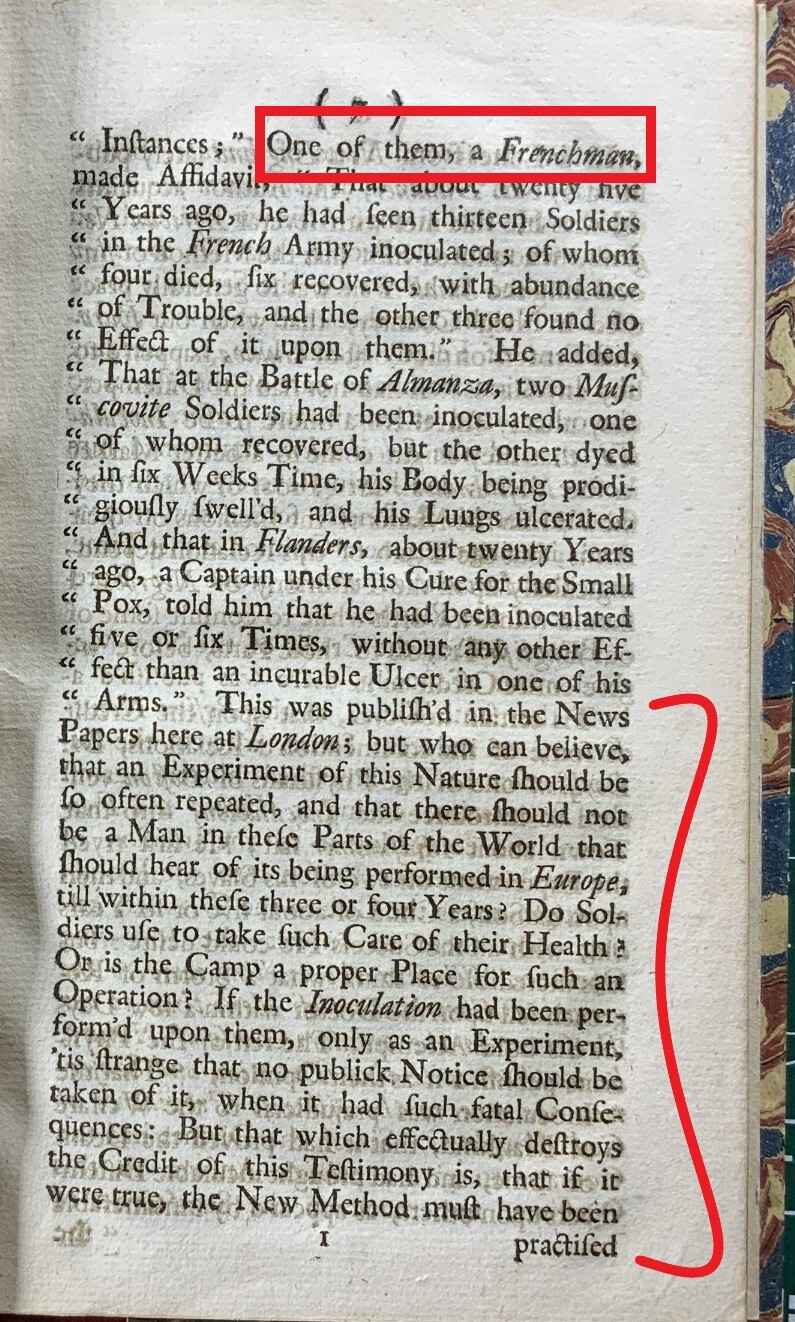

Such detailed scholarly processes, in addition to the wealth of information produced by English medical professionals, built an ethos steeped in cultural superiority. Especially in regard to English knowledge of smallpox, there was a hesitancy to accept foreign accounts of the disease, as described in Inoculating the Small-Pox in New England.

“One of them, a Frenchman, made Affidavit … but who can believe that an Experiment of this Nature should be so often repeated, and that should not be a Man in these Parts of the World that should hear of its being performed in Europe? Do Soldiers use to take such Care of their Health… But that which effectively destroys this Testimony is, that if it were true, the New Method must have been practised” (Coleman 1722).

An immediate questioning of a French soldier’s encounters with smallpox suggests that for England, and in turn New England’s anglophilic population, knowledge from other cultures was diminished. Why might this be? Could it be solely based in ethnic and geographical differences, or is there more here to unravel? A glance at the title page suggests that religion was another important factor for xenophobia: references to scripture places English medical endeavors in a heavily religious environment. Knowing that France in particular was predominantly Catholic, it makes sense that Anglican England held deep rooted angst for their inland, Catholic neighbors.

With this additional religious lens for interpretation, might the respected and reputed authority, for New Englanders, share Protestantism as a core basis for trust in medical knowledge? Similarly to their mother country across the Atlantic, New England’s gospel was flavored with the remnants of King Henry VIII’s separation from the Pope in Rome. In short, religious differences also limited the scope of this transference of knowledge.

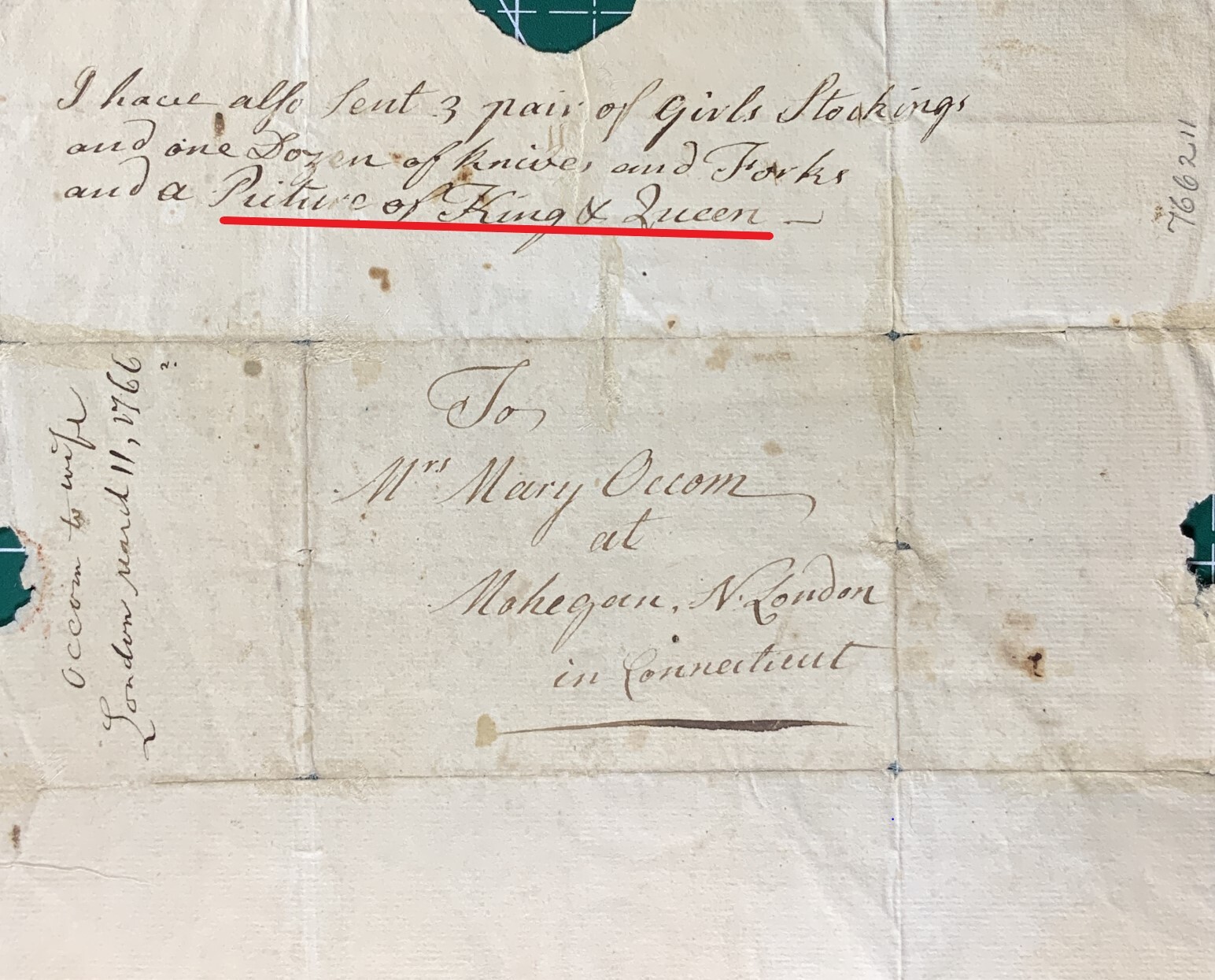

The identities of Indigenous peoples in New England also enter the complicated intersection of religion, culture, and knowledge. Samson Occom, a pastor and member of the Mohegan tribe native to what is now Connecticut, traveled to England to raise funds for Moor's Charity School in order to educate other Indigenous men (the money was then repurposed by Eleazer Wheelock to help found Dartmouth College). A letter to his wife written in 1766 documents Occom’s smallpox inoculation he received in England. Drawing on the previous logic of both cultural and religious ties to England, it makes sense that Occom chose London as the site of his inoculation: more trust in the efficiency and quality of English inoculations was placed than in the local ones. Additionally, by including portraits of the King and Queen in the letter, he demonstrated his fervent fondness for England.

“I have also sent a Picture of King & Queen” (Occom 1766).

As an important religious leader, Occom's influence went far and wide among the Indigenous community in New England. Following the First Great Awakening in the 1720s, Occom helped christianize, and unavoidably anglicize to an extent, many other Indigenous Americans from several local tribes. The mark of English colonialsm transcended just the English settlers: with a changing landscape marked by Old World disease, new religion, and a changing, and unjust, system of racial hierarchy, came new, altered life pathways for the descendents of the original inhabitants of New England.