The Hovey Murals and Sonic Space

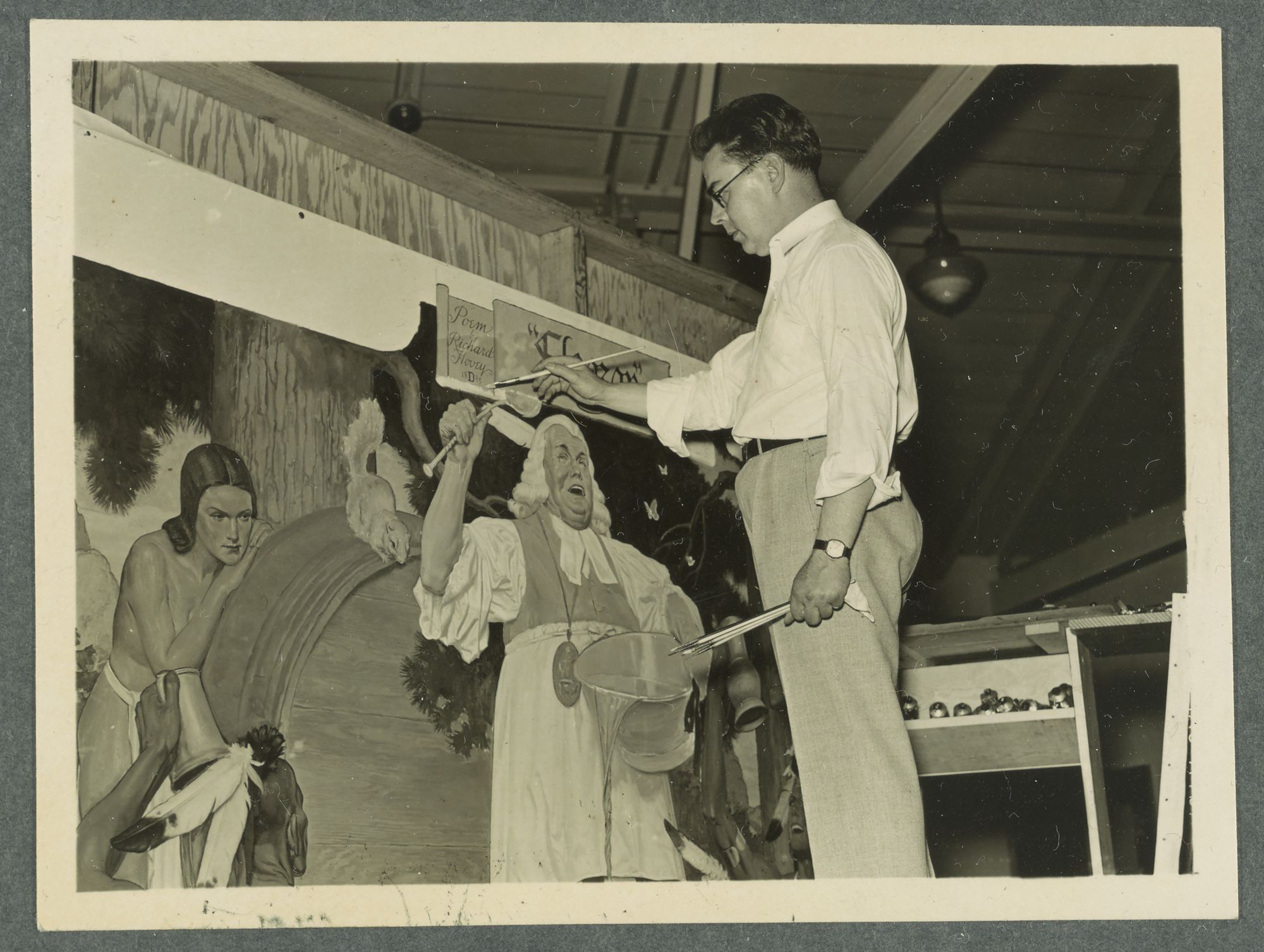

The Epic of American Civilization, a series of 24 frescos by José Clemente Orozco, was recently designated a National Landmark by the Department of the Interior.[1] Much less celebrated, however, are Walter Beach Humphrey’s (Class of 1914) set of murals painted in response to Orozco’s work. Humphrey’s murals, known today as the Hovey Murals, have a unique tie to music at Dartmouth. To understand this connection, one must first understand the relationship between The Epic of American Civilization and the Hovey Murals.

Orozco, a celebrated Mexican painter, finished his set of frescos in 1934 and was immediately met with fierce criticism from alumni. Unlike other Great Depression-era murals that “[celebrated] America,” his work instead “[satirized] both academia and New England culture.”[2] Among these zealous alumni was Humphrey, who “petitioned Dartmouth president Ernest Martin Hopkins to counter the Mexican painter’s visual polemic with ‘a real Dartmouth mural.’” In fact, in the 1937 issue of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, Humphrey pleaded with his fellow alumni, writing,

“So – give me some paint and a wall-space that ain’t

All done on the Mexican plan,

And I’ll make it sing with verses that ring

In the heart of each true Dartmouth man!”

Still 35 years away from coeducation, Humphrey’s message rang loud and clear with the vision of Dartmouth that white men revered, and in 1937 he was given a space in the Thayer dining hall to execute his vision. Not only was this dining space only for Dartmouth faculty and students (unlike the library where The Epic of American Civilization stood), but wanting to cater to the masculine wishes of the audience that used the space, Humphrey based his murals off none other than the song “Eleazar Wheelock.” As the antithesis to the avant-garde work of Orozco, Humphrey’s murals did not push the boundaries of art forward. Rather, they held in stasis ideas of the past, a concept only reinforced by his use of an old Dartmouth traditional.

The panels depict extremely stereotypical and demeaning images of American Indians. The men are all wearing feathers in their hair and are partially clothed. The women — keeping in line with the words “ten squaws” — are all depicted in a hypersexualized manner, either partially or fully nude. An implicit mocking of Native Indian intelligence is also apparent; one panel depicts two women looking at a book upside down.

That these images were hanging from the walls where generations of privileged, white males dined only reinforced their status as the pinnacle of Dartmouth’s social hierarchy. Although there was no musical act, per se, the words of “Eleazar Wheelock” are literally written on the walls. The belittling of Native Americans in the paintings, the White Savior depiction of Wheelock, and the singing of the song itself all created an atmosphere that allowed students during the era of the Hovey Grill to immerse themselves in a “feel-good” environment where an idealized narrative of race-blind colonization at Dartmouth could persist. We can probably assume that American Indian students were not allowed entry into the exclusive dining club, that is if they had sought to do so in the first place. Thus, Native American representation in the social space of the Hovey Grill was limited to symbolism in lewd depictions rather than actual engagement.

We examined some case studies of music at Dartmouth, past and present, to answer the question: who gets to participate? Usually (and unsurprisingly), the socially powerful. However, in evaluating the legacy and impact of the Hovey Murals, one encounters a fundamentally different question. Although Native Americans were not allowed/chose not to participate in a space that was filled with art about them, the placement of power was less about participation in the music itself, but more about the physical space that it occupied. Now the question becomes: where do we participate?