Opinions and Disagreement: Latinos at Dartmouth Across a Changing Educational Context

"Affirmative Action: In the United States, a set of laws, policies, guidelines, and government-mandated and government-sanctioned administrative practices, including those of private institutions, intended to end and correct the effects of a specific form of discrimination. It aims to reduce present discrimination against members of targeted groups and to increase their numbers within certain occupations and professions and at universities and colleges."

Walter Feinberg, The Oxford Handbook of Practical Ethics

Change Hits the United States

Between the 1970s through the 1990s, various political and social changes affected the educational setting of the United States. Following the signing of the Civil Rights Act in the 60s, various policies were proposed in order to redress the disadvantages that had historically been imposed on minorities and other marginalized groups. These policies became known collectively as part of the concept of ‘Affirmative Action’. This digital exhibit showcases the changes taking place across the U.S in relation to those taking place at Dartmouth surrounding affirmative action with an emphasis on Latinos in the college.

Originally established under Executive Order 10925 in 1961, affirmative action policies emphasized a goal of achieving labour opportunity for all. The executive order established the Preisdent's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and required that government contractors to "take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed and that employees are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin." This was the first time the term ‘affirmative action’ was used in regards to a specific federal order or policy.

In 1965, the concept of affirmative action was expanded on by Lyndon B. Johnson with Executive Order 1126. This order prohibited "federal contractors and federally assisted construction contractors and subcontractors, who do over $10,000 in Government business in one year from discriminating in employment decisions on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin."

Since the initial proposal and implementation of affirmative action policies, these have remained controversial, drawing criticism from politicians, private institutions, administrators, and as well as students. Though affirmative action policies were proposed as a method to reverse the historical biases and implications of racism and segregation, some viewed them as ineffective while others viewed them as unfair. Some argued that the measures placed importance on race over merit while others expressed their necessity in order to address the structural inequalities within the educational and labor setting in the country. Through the courts, affirmative action policies were contested time and time again.

In 1978, the disagreement between affirmative action advocates and critics took to the Supreme Court with the case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265. In this case Allan Bakke argued that by not being accepted to the medical school at the University of California, Davis because 16% of admission spots had been reserved for minority students, he was facing “reverse discrimination”. He sued the university presenting evidence that his grades, test scores, and qualifications exceeded those of many minority students that had been admitted to the school. Bakke argued that the “reverse discrimination” he faced violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In its landmark decision, the court ruled that the ‘race quotas’ used by the university were unconstitutional, however it held that the use of race as a factor in admissions decisions within higher education settings was constitutionally permissible.

The Change Hits Dartmouth

Though tucked away in the New England woods, Dartmouth College was also affected by the changes that arose as the educational setting of the U.S shifted. With the expansion of affirmative action, the college revisited proposals to allow for it to become a co-ed institution. Though Dartmouth became a co-ed insitution in 1972, the initial change was met with major opposition from a small but vocal minority. This minority spoke out against what they percieved as a horrifying change to the tradition of the college which until then only admitted men. This is important to note because when discussing the Dartmouth context, the college has historically dealt with the existence of opposing opinions regarding the admission of students from various marginalized groups. Showcased below is a quote expressing oposition to the changes, a negative sentiment shared not only against women, but against other groups such as Latinos as well.

"Although most undergraduates enthusiastically supported the decision to admit women, a small, highly vocal minority did not hesitate to voice dissenting views. In a dormitory meeting in advance of the decision, in the presence of assistant provost Marilyn Austin Baldwin, at that time the highest-ranking woman administrator at Dartmouth, one student said, “I just want you to know I don’t consider women to be my equal. I don’t want them in the classroom with me, and the woman I marry had better know her place or I’ll knock her down into it."

Weiss Malkiel, "Keep the Damned Women Out": The Struggle for Coeducation, p.469

The Increase of Latino Enrollment at Dartmouth

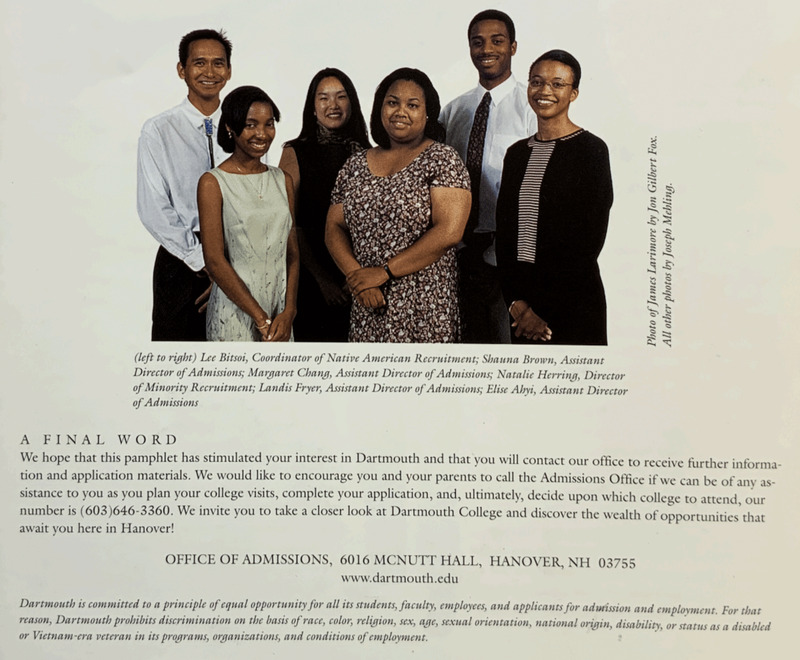

From the late 70s through the 90s, the administration of the college made various efforts to increase the enrollment not only of women, but also that of other marginalized groups such as Latinos. These efforts were made at both an administrative and student level. At the administrative level, the Dartmouth Office of Admissions made efforts to attract Latino students through its publication of "Latinos at Dartmouth", a recruitment oriented pamphlet that emphasized the different courses and experiences available for Latinos who chose to attend the college. Yet even at the adminsitrative level, there was an intense disagreement between Latino advocates and the administration they worked for. Though minority enrollment rates were increasing across Ivy League universities, the vague efforts to increase enrollment as well as the lack of resources provided to students led to this intense disagreement.

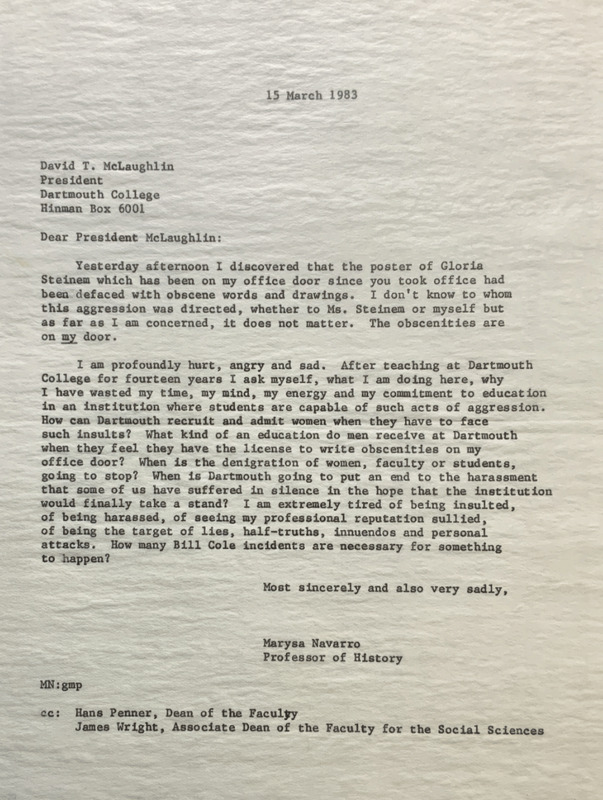

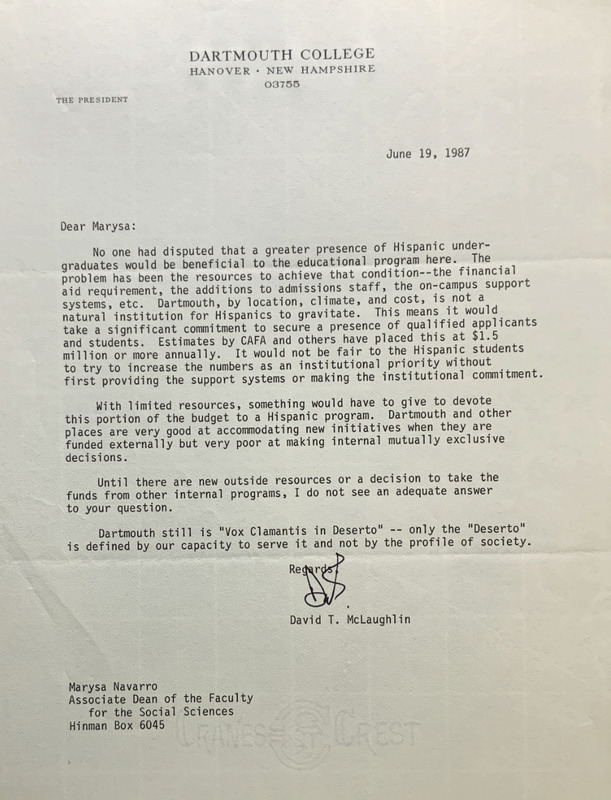

These differences are shown through the correspondence between Marysa Navarro and other figures such as David T. McLaughlin, then president of the College. Within these pieces of correspondence, the nuances surrounding language in reference to Latinos at Dartmouth can be seen. From being identified as “Hispanics” to “Latinos/as”, the terms and identifiers used by members of the Dartmouth administration showcase the labels used to describe the Latino community at the university and how it was perceived by figures such as Dartmouth President David T. McLaughlin. In addition, the usage of specific terms and labels was influenced by students themselves within organizations such as La Alianza Latina as well as The Dartmouth. These labels intersect with the concepts of national politics in order to paint a full picture of the Dartmouth context surrounding Latinos.

Though the Dartmouth administration made various attempts to increase the enrollment of minority populations at the school, these efforts come too slowly for many including administrators such as Marysa Navarro. With continuous excuses such as a lack of resources or budget, other administrators like President McLaughlin attempted to mitigate these complaints by expressing their understanding and continous "efforts". When referring to the matter of Latino enrollment at Dartmouth however, the use of terms as the “Hispanic issue” or the “Latino problem" placed Latinos, not as a population in need of further representation, but rather as an issue needing to be appeased with larger rates of recruitment.

During this period, the country's educational setting had continued to shift as well with the continuation of the affirmative action conflict. The 80s marked the political separation between affirmative action critics and advocates. It was in 1980 when then presidential candidate Ronald Reagan challenged the Carter Administration's affirmative action initiatives. Though the 1980 Democratic platform asserted that, "An effective affirmative action program is an essential component of our commitment to expanding civil rights protections," the Republican platform argued that, "Equal opportunity should not be jeopardized by bureaucratic regulations and decisions which rely on quotas, ratios, and numerical requirements to exclude some individuals in favor of others”, referring to such regulations and decisions as “inherently discriminatory”.

In 1986, the Supreme Court case Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S. 267 took the center stage of the affirmative action fight. In its 5-4 decision, the court ruled that the government when implementing any affirmative action policies had two duties: 1) to justify racial classification with a compelling state interest, and 2) to demonstrate that its chosen means were narrowly tailored to its purpose.

Latinos and the Dartmouth Student Body: A Nonexistent Monolith

At Dartmouth, the increase of Latino enrollment had already been a source of contention with Latinos posing a threat to the then existing status quo. Many of the obstacles they faced expanded across the context of affirmative action which presented the rise of the Latino Studies Program, Latino organizations, and Latino affinity housing as a threat to the "tradition" of the institution.

As the changes regarding education occured across the country, Dartmouth's student body took on a leading role in recruiting students of all backgrounds. Though minority enrollment had increased at the institution, the influence of affirmative action became a source of division within this very student body.

For Latinos at Dartmouth, one of the primary organizations available was La Alianza Latina. Through its advocacy and resource creation, this campus organization made various efforts to increase the amount of resources available to Latino students in efforts to better the Latino experience in campus. This meant that the organization took various actions in efforts to increase membership and funding. In addition, through political protests and advocacy letters, the group aimed to aimed to increase awareness surrounding Latino issues in the United States. This occured as the the controversy surrounding affirmative actions in the U.S heightened.

Though seemingly a united front, often confused for a monolith, the Latino population, specifically within Dartmouth held many differences of opinion regarding topics such as affirmative action. In addition, the passage of bills such as Proposition 187 in California further showcased the differences of opinion within the population.

California's Proposition 187 was passed in 1994. This ballot initiative entailed banning undocumented individuals, then still commonly referred to as "illegals" from accessing basic public services such as non-emergency health care and both primary and secondary education. In addition, the proposition would have required public servants like medical professionals and teachers to monitor and report on the immigration status of those under their charge. As the state reached an economic slump, supporters of the proposition justified it as a money saving measure against those who were "draining the system". Though passed by a 59% vote in its favor, the proposition was immediately challenged in the courts and ultimately never implemented. California has since formally repealed Proposition 187 and enacted some of the United States’ most sweeping protections for undocumented individuals.

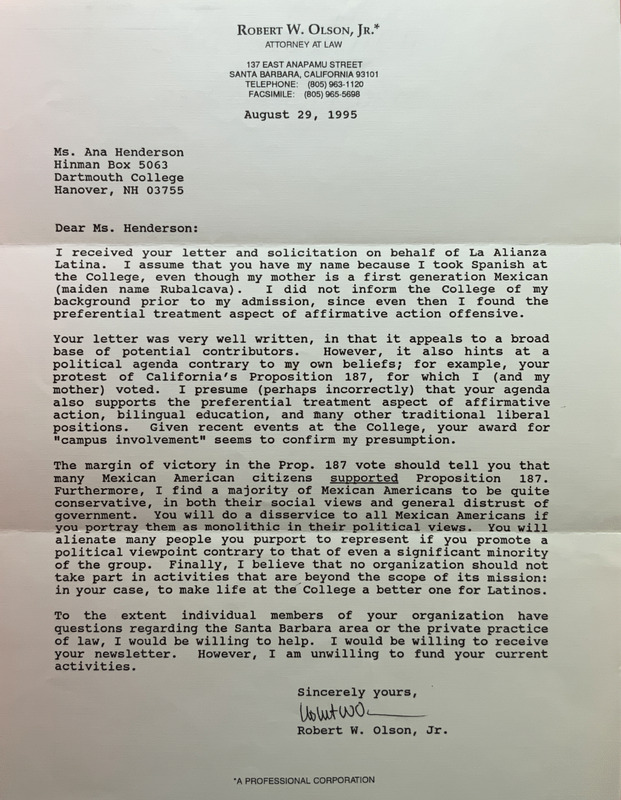

Following the passage of this proposition, La Alianza Latina expanded its action plan from hosting weekly movies and study halls, to the sponsoring of Latino/a authors’ visits to advocate against the proposition. This expansion was not necessarily supported by all members of the student and alumni population. For instance, in a response letter to a donation request, the debate regarding affirmative action was brought up with the responder, Robert W. Olson Jr., a Dartmouth alumn and son of a first generation Mexican woman, seemingly reprimanding Ana Henderson for the political activities La Alianza Latina appeared to be involved with. In his response letter, Olson Jr. reaffirmed his firm stance against affirmative action. He alsodeclined to send any financial donations to the group as long as it continued taking part in protests against policies such as Proposition 187. Olson Jr. fiercely argued that the majority of Mexicans in the state of California voted for the measure since it was passed by voters themselves. His letter showcased a perspective in which the vote in favor of Proposition 187 displayed a conservative social and political view. Overall this perspective demonstrated a conflict within the Latinos associated with Dartmouth, disproving the concept of a monolithic group within the campus.

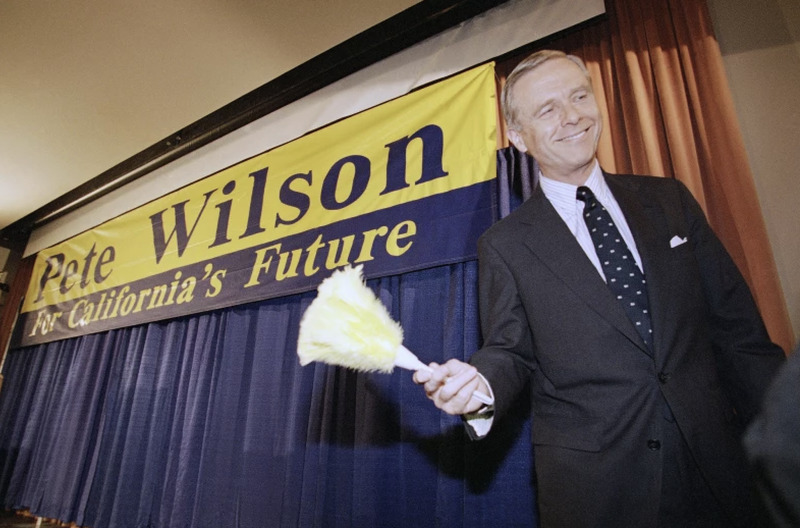

As efforts to recruit Latino students increased through the 90s, the concept of affirmative action became more and more contested and discussed as states such as California banned affirmative action policies within secondary education settings. The state passed Proposition 209 in 1996. This initiative amended the state's constitution to ban state and governmental institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity, specifically in the areas of public employment, public contracting, and public education. The proposition, endorsed by then Governor Pete Wilson, passed with 55% of voters in favor and has been in place since then. It became a symbol of the growing sentiment against affirmative action.

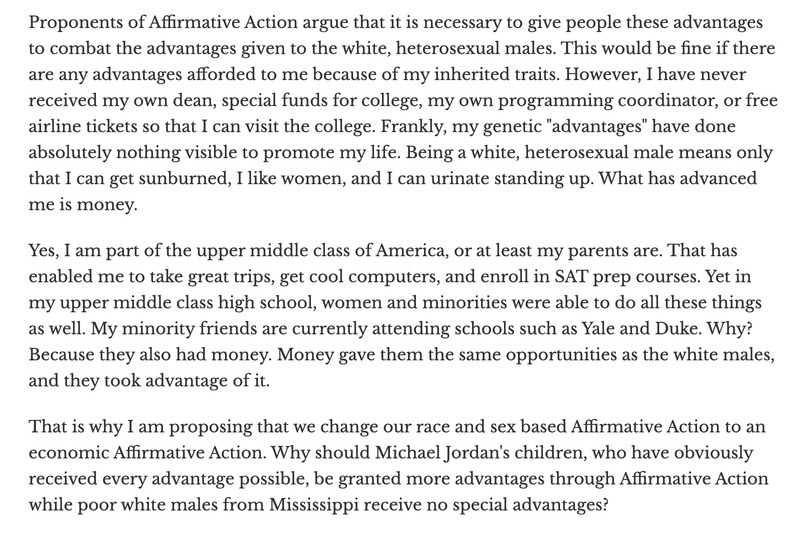

At Dartmouth, that sentiment was shared by certain members of the student body. In 1999, a scathing op-ed piece was digitally published by the Dartmouth, the schools newspaper. Written by Mark Hill, then a student at the college, the piece rejected the idea that white heterosexual males received any advantages over students of any other race, gender, or sexuality. The piece argued in favor of economic affirmative action policies rather than affirmative action policies based on race, stating that there was a double standard regarding resources for Black and Latino students compared to those for white students.

Conclusion

The argument surrouding affirmative action has continued since the 90s and its influence has continously reached the Dartmouth campus. Most recently, in 2016, a coalition of 132 Asian-American organizations filed a complaint with the Federal Departments of Education and Justice accusing Yale University, Dartmouth College, and Brown University of discriminating against Asian Americans in their admission processes. The groups argued that racial quotas and caps used to maintain “ideal racial balances” and had kept the percentage of Asian-American students at these schools unchanged over the past 20 years. Where these campaigns will go? Only time will tell.

Dartmouth College has changed many of its policies to adapt to the federal and state changes that have taken place since the conception of affirmative action practices. Located in New Hampshire, the college is bound by both federal and state laws. As new cases make their way to the Supreme Court, there are various implications for the future demographic make up of the college. Currently, the administration continues to promote the concept of diversity within the campus, emphasizing an affirmative action plan for its employees and a diversity effort plan for its students. Every year or so, the plan is reassessed and a new report is presented. This however, only means that Dartmouth, and of course, the role of Latinos within the campus will continue to change across the shifting educational context of the U.S.

"Diversity at all levels is critical to Dartmouth's mission of providing an environment that combines rigorous study with the excitement of discovery. As an institution of higher education, Dartmouth is defined by the belief that a multiplicity of values and beliefs, interests and experiences, intellectual and cultural viewpoints enrich learning and inform scholarship."

Dartmouth College Diversity Mission Statement

References

Associated Press. The Bakke Case and Affirmative Action. American Experience. The Public Broadcasting Service, 1978. http://www.shoppbs.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/eyesontheprize/story/img_22_bakke_03.html.

Dartmouth College Office of Institutional Diversity and Equity. “Reaffirmation of Policy.” Institutional Diversity and Equity. Dartmouth College, 2022. https://www.dartmouth.edu/ide/policies/reaffirm.html.

Dartmouth Office of Admissions, "Office of Admissions "Latinos at Dartmouth" Pamphlet Back Page, 1999," 1999, Box 1, Folder 1, Latino Folder. Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College.

Feinberg, Walter, and Hugh LaFollette. “Affirmative Action.” The Oxford Handbook of Practical Ethics, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199284238.003.0012.

Fuchs, Chris. “Complaint Filed against Yale, Dartmouth, and Brown Alleging Discrimination.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, May 23, 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/groups-file-complaint-against-yale-dartmouth-brown-alleging-discrimination-n578666.

Galbraith, Bob. Governor Pete Wilson Smiling Following the Passage of Prop. 187 in California, 1994. The Los Angeles Times. The Los Angeles Times, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-11-17/proposition-187-pete-wilson-latinos.

Hill, Mark. “Another Kind of Racism.” The Dartmouth. The Dartmouth, April 22, 1999. https://www.thedartmouth.com/article/1999/04/another-kind-of-racism.

Malkiel, Nancy Weiss. “Dartmouth: Our Cohogs.” Chapter. In "Keep the Damned Women out": The Struggle for Coeducation, 464–88. S.l: Princeton University Press, 2018. https://muse-jhu-edu.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/book/56697/.

David T. McLaughlin. "David T. McLaughlin to Marysa Navarro Letter, 1987." June 19, 1987, Box 1, Folder 22, Marysa Navarro Papers. Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College.

N.A. “Affirmative Action.” NAICU. National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, 2016. https://www.naicu.edu/policy-advocacy/issue-brief-index/regulation/affirmative-action.

N.A. “Regents of the University of California v. Bakke.” Oyez.com. Oyez, n.d. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1979/76-811.

Navarro, Marysa. "Maryssa Navarro to David T. Mclaughlin Letter, 1983," March 15, 1983, Box 1, Folder 22, Marysa Navarro Papers, Special Collections, Dartmouth College.

Office of the Federal Register. “Executive Orders: Executive Order 11246--Equal Employment Opportunity.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, 2016. https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/11246.html.

Olson Jr., Robert W. "Robert W. Olson Jr. to Ana Henderson Response, 1995," June 19, 1987, Box 1, Folder 1, Friends of La Alianza Latina Papers, Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College.

Patterson, Orlando. “Affirmative Action: The Uniquely American Experiment.” The New York Times. The New York Times, January 30, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/30/books/review/the-affirmative-action-puzzle-melvin-i-urofsky.html.

Schmidt, Peter. “New Hampshire Ends Affirmative Action Preferences at Colleges.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 4, 2012. https://www.chronicle.com/article/new-hampshire-ends-affirmative-action-preferences-at-colleges/.

Tran, Kenneth. “At Dartmouth College, an Environment of Wealth and Privilege Might Be Changing In-Campus Life, but Certainly Not in the Lecture Halls.” Granite State News Collaborative. Granite State News Collaborative, July 9, 2021. https://www.collaborativenh.org/college-diversity-project-stories/2021/7/9/at-dartmouth-college-an-environment-of-wealth-and-privilege-might-be-changing-in-campus-life-but-certainly-not-in-the-lecture-halls.