Constructing Latinx Community at the Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean (LALAC) Affinity House

A final project for LATS 3 by Samrit Mathur '23.

Affinity houses at Dartmouth College are conduits for community building for students of marginalized identities. Dartmouth’s six affinity houses, the LALAC House, Asian American House, Triangle House (for LGBTQ+ identifying students), Gender Equity Floor, Global Village (for international students), and the Shabazz Center for Intellectual Inquiry (for African descent students), provide opportunities for intellectual exploration that extend beyond the walls of the classroom through programming tailored to underserved student groups on campus. In this digital exhibit, I seek to leverage place analysis, faculty letters, and student testimonies to understand how the LALAC house facilitates community building among Latinx students at Dartmouth.

To begin with, I will construct a historical narrative of how the LALAC house came to fruition. Among student organizations, there was a general sense of discontent with the La Casa House, a long-standing Spanish-language focused residential space, with La Alianza Latina criticizing the College’s choice to host Latin American cultural programming in a non-cultural setting. Specifically, La Alianza Latina lambasts La Casa for “not historically supporting U.S. Latino students” and rejects a planned conference on Latin American identity to be held there. The student group published a campus-wide newsletter in 1994 specifically advocating for a committee to discuss issues pertaining to the U.S. Latino community, whose concerns ought to be addressed independently of the broader Latino and Spanish-speaking communities.

On the other hand, a letter from the Dean of the College Lee Pelton in 1994 pushes back against the formation of an affinity house for Latin American culture, arguing that it is impossible to “establish priority needs based on culture alone” and that “the needs of U.S. Latino students can be met through an association with La Casa.” Although by 1994 the Shabazz House, Native American House, and Global Village had already been constructed, Pelton felt that the creation of a LALAC house would lead to a slippery slope whereby all cultural groups would demand their own affinity house. Historically, Dartmouth has resisted the construction of exclusive spaces for marginalized students, including the Shabazz House in the 1970s. Dartmouth initally failed to provide sufficient residential capacity to the Shabazz House (originally called Cutter House) and rejected proposals by Black students to rename the house after Malcolm X. Continuous advocacy on behalf of student organizations such as the Afro-American Society paved the pathway for larger, more autonomous affinity houses that would be later constructed at Dartmouth.

Three decades after the establishment of the Shabazz House, advocacy on behalf of LALACS program faculty (particularly Professor Orlando Castillo) and La Alianza Latina (especially president Sonia Price ‘99) allowed the LALAC house to be officially established in 1999 with a residential capacity of 10-12 students. Their advocacy included signed campus-wide petitions, student newsletters, and written letters to members of Dartmouth's administration.

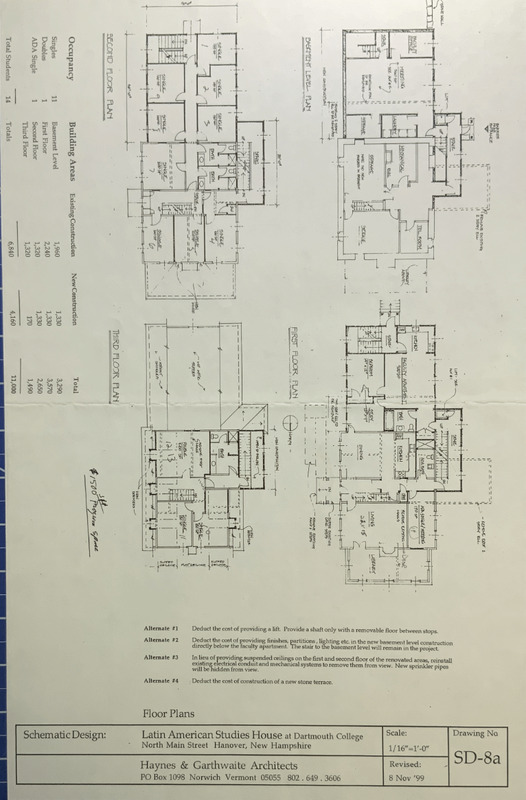

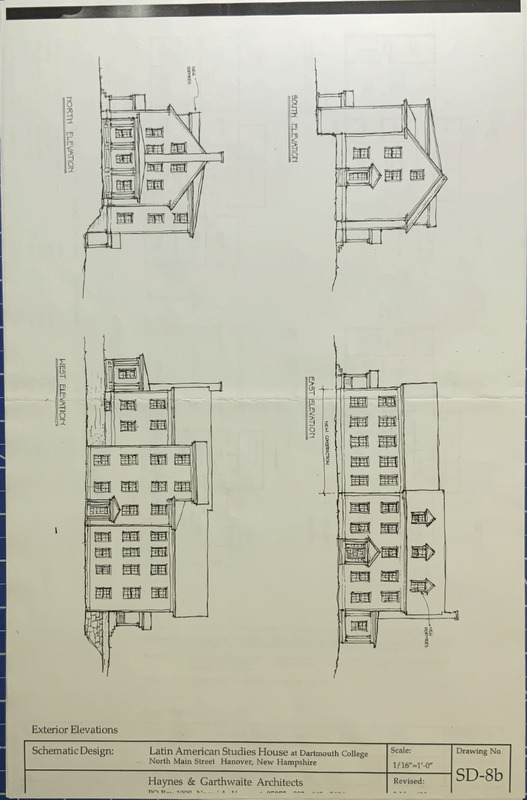

Next, I will provide a place analysis of LALAC, using floor plans and wall murals to identify how the structure of the building facilitated community-building among Latinx students at Dartmouth. Previously the Office of Public Affairs on North Main Street, architects redesigned the building to meet the academic and cultural goals outlined by the college, including the addition of new dorm rooms, a terrace, accessible walkways, an in-house library and study area, an adjoined faculty apartment, and an expanded kitchen. The addition of library and study spaces, as well as an expansion in residential capacity, was a critical element in fulfilling the promise of affinity housing, extending engagement with Latin American culture outside the classroom walls. Terraces and a larger kitchen allow for more elaborate cultural programming to take place within LALAC, including ballet folklorico events throughout the early 2000s and weekly community dinners. The adjoined faculty apartment would increase the ability of advisors to form genuine connections with Latinx students in spaces most comfortable for them.

Spatial layouts have historically been integral to the success of organizations with community empowerment goals. For example, the Young Lords organization leveraged their office space to foster strong community bonds and motivate members in the fight for self-determination for all colonized peoples, with special emphasis on Puerto Ricans. Located in the majority Black and Latinx neighborhood of Harlem, the Young Lords’ office was equipped with telephone lines, furniture, and computers to maximize their organizing capabilities; posters of Che Guevara and other revolutionary leaders surrounded the room, reinforcing the Young Lords’ revolutionary objectives. Both the Young Lords and LALACS use space thoughtfully to build strong communities and meet their institutional promises

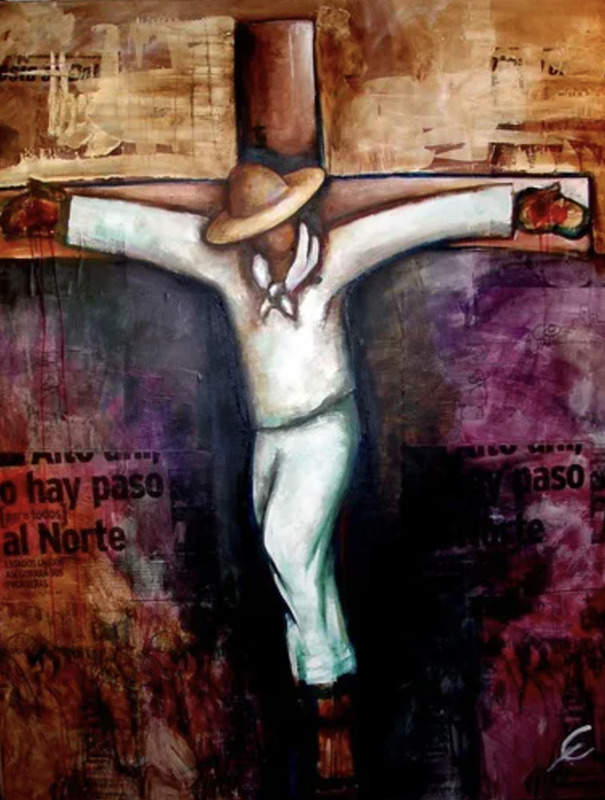

Beyond the architecture of the house, commissioned artwork within the house facilitated inclusion and belonging for Latinx students at Dartmouth. Ernersto Cuevas ‘98 painted a 6-panel mural on the first floor of the LALAC house, telling a story of migration, oppression, and exploitation. The murals first couple panels depict America as a land of opportunity and Latinxs leaving their homelands, ravaged by colonialism and exploitation, in search of a better life. The next two panels show Latinx farmworkers and laborers supporting the traditional American family, without recognition or the opportunity to participate in the promises of the American dream. The final 2 panels show a contrast between corporate American life and blue-collar life, the division that emerged at the turn of the 21st century between Latinx people. Cuevas’ mural provides a relatable artistic vision of the Latinx historical and present experience, emphasizing the importance of Latinx people throughout America’s history, their role in constructing America’s opulence, and the oppression and division they face in the present day. Artwork that centers the Latinx experience in a space for Latinx students who may feel underserved at Dartmouth is a powerful message that communicates relatability, inclusion, and belonging.

At predominantly white institutions (PWI) such as Dartmouth and more broadly in the United States, Latinx history is often dismissed and, when covered, treated as inherently separate from American history. This separation “others” U.S. Latinxs and can contribute to a sense of lack of belonging. In Nuestra America, Vicky Ruiz seeks to prove that Latinx history is American history, arguing that the assimilation, migration, and resistance of Latinx people are all formative elements of American history and an improper understanding of these concepts has led to an incomplete historical vision. In tracing American history from Spanish colonization to the establishment of Latino Studies programs at U.S. universities, Ruiz claims American history and Latinx history are one and the same, with Latinx people playing a critical role in every historical moment. Ernesto Cuevas’ mural in the LALAC house serves a similar function. By unveiling the obscured saviors of the American family, Latinx farmworkers, Cuevas paints an inseparability of Latinxs and Anglo American families. His mural centers the Latinx experience in a culturally Latinx space, linking inclusion at a historical level with inclusion at Dartmouth College today.

Finally, student testimonies from The Dartmouth allow us to analyze the outcomes of living at LALAC in fostering Latinx inclusion and belonging. At a high level, students report that affinity housing as a concept fosters community and provides a space for marginalized students to build community with people who can relate to their struggles. Adriam Moya ‘24 describes his experiences in the LALAC house to The Dartmouth as follows

“I wanted to find a place where I actually felt community and not just [like] the outsider,” Moya said. “When I go into the living room and do some work, I just want to relax, and I don’t want to worry if I’m understanding the references or if people even understand me.”

Communities such as LALAC help students cope with the culture shock that can accompany attending a predominantly white institution. Affinity housing may be one of the only options on campus for students of color to feel included in the fabric of the Dartmouth community.

"I just felt comfortable in it, with the people who are there, the new faces of Latinos at Dartmouth," explained LALACS resident Luis Lopez '03.

Surrounding yourself with others who look like you and have similar shared experiences can enhance feelings of connection to one's cultural heritage, even when displaced far from home. It is clear that the LALAC House, with its thoughtfully designed architecture, explicitly cultural emphasis, and strong student bonds, continues to serve as an important conduit in the formation of Latinx community at Dartmouth.