Eunice A

By Eunice Antwi '25

“Turning our attention to the everyday, to private, concealed, and even intimate worlds, is essential to excavating bondwomen’s resistance to slavery because women’s history does not merely add to what we know; it changes what we know and how we know it,”

- Stephanie Camp.

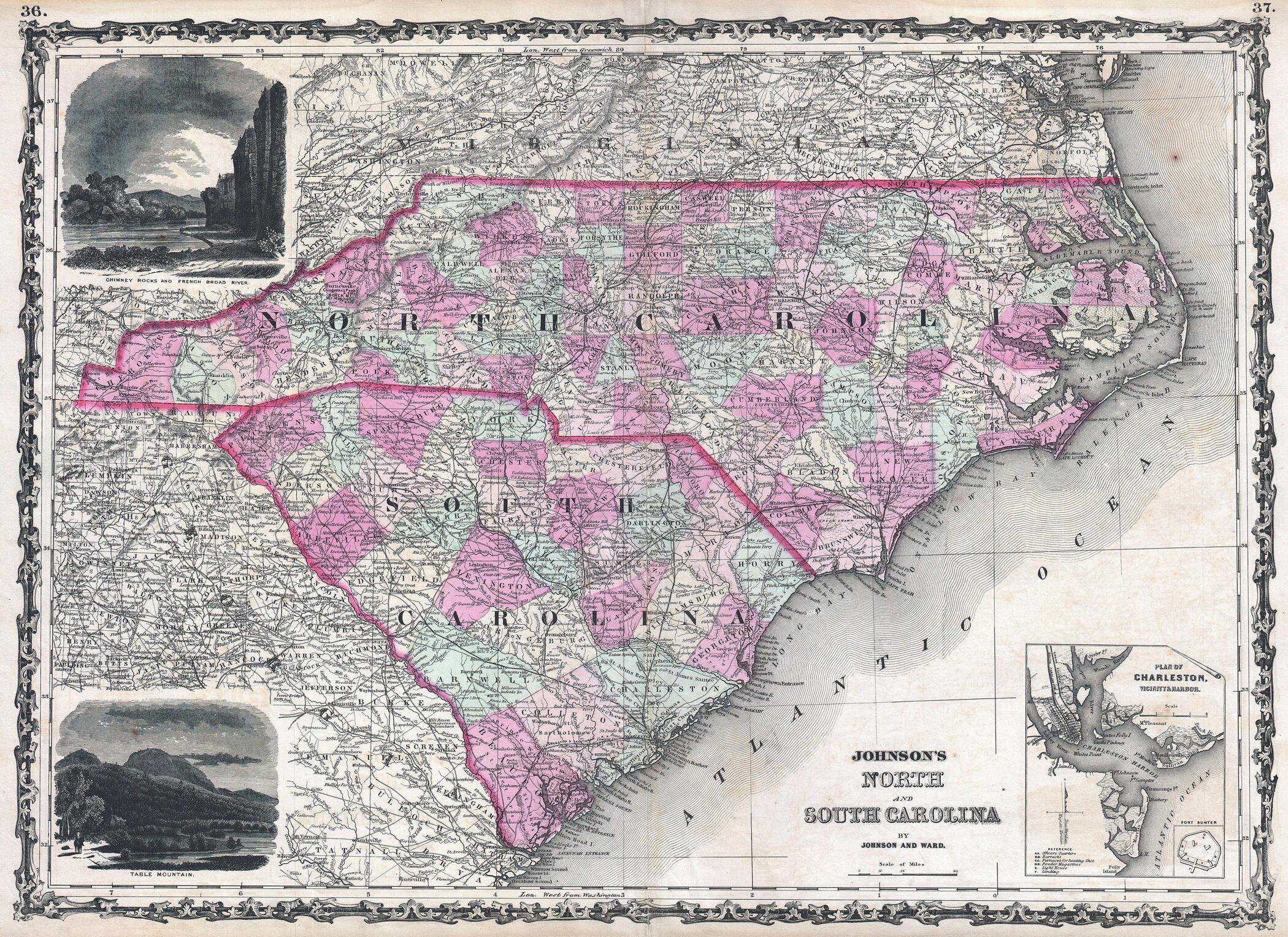

This exhibit hopes to explore the anatomy of a female runaway. What drew her to decide enough was enough and proceed into unmarked territory? To better understand the gravity of her situation, it is important to first situate ourselves in her reality. During the Antebellum period, the confinement of enslaved people was a fluid practice. Often, southern states would look to one another and mirror the systems they saw carried out. This exhibit in particular will have an emphasis on the history of North and South Carolina, but other states will be mentioned to complete the narrative. Once a foundation has been established, runaway notices will be stretched along the archive to see what drove these women to full flight. Thank you for viewing my exhibit and enjoy!

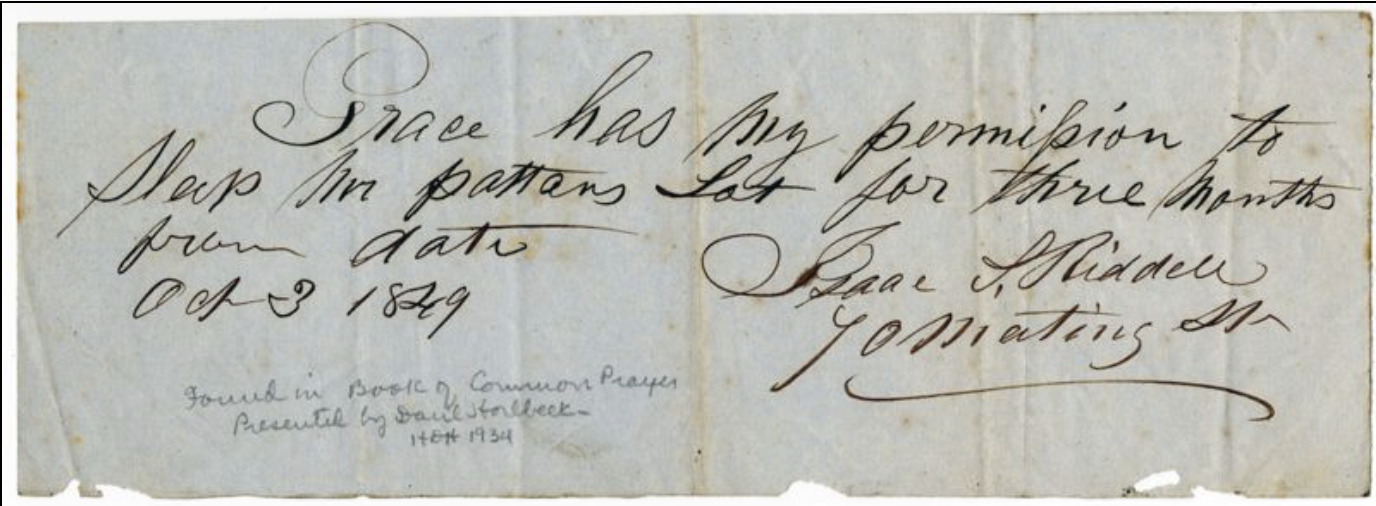

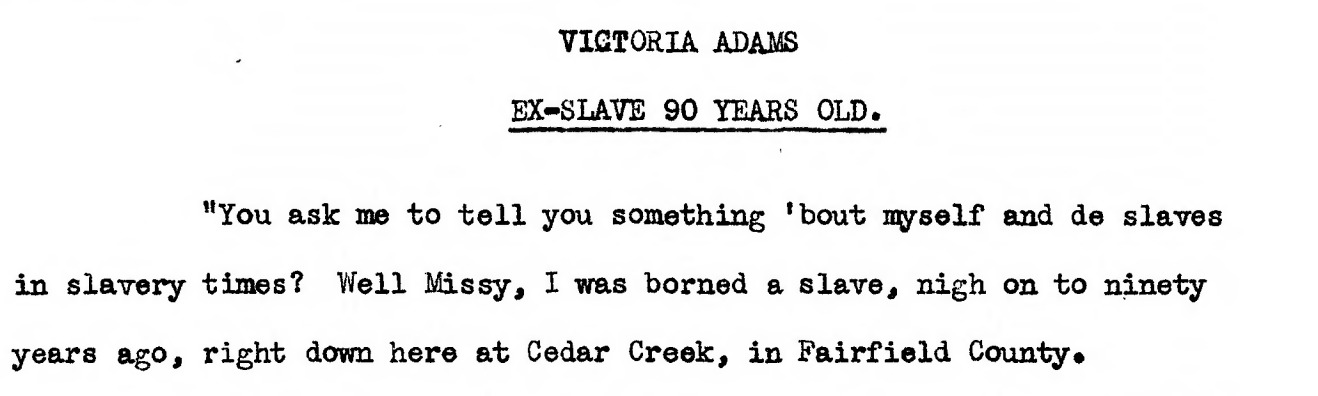

Life on the plantation during the Antebellum period was filled with daily horrors. Planters worked tirelessly to confine the movement of their enslaved people by implementing “morning reveilles, slave patrols, curfews, and laws requiring passes and banning independent travel or meeting” as a means to limit and control the movement of their enslaved men and women (Camp, 6). However, when sex is added to this “geography of containment,” we see that women face even further restrictions. Many of the founding slaveholders in South Carolina came from Barbados and they brought this mindset with them. In 1690, these holders created a new means to regulate slave activity by implementing a “ticket system” based on what occurred in Barbados (Camp, 14). This system was different from anything in the United States South at this point, for it prohibited enslaved people from leaving their plantations without a ticket (Camp, 14). The tickets were required to contain the enslaved person’s name, where they were leaving from, where they were going, and how long they were to stay there (Camp, 14).

If an enslaved person was found without a ticket, their punishment ranged from whippings to death (Camp, 14). Each state had slightly different amendments to the system, for example, “North Carolina went as far as to sketch the route that enslaved travelers were to take when it demanded that the bearers of passes ‘keep the most usual and accustomed road’” (Camp, 16). With this new system, enslaved people saw their mobility truncated. Women, however, saw their opportunities to leave the plantation reduced to almost zero. Due to the gender roles of the Antebellum period, the work that provided the chance to leave the plantation was typically reserved for men (Camp, 28). This also resulted in women running away in a lower percentage in comparison to men because they lacked the relative knowledge of geography beyond the plantation (Camp, 38). Moreover, men were often separated from their families, so the passes gave them access to visit their loved ones. There were rare instances where women were granted passes, and these tasks usually concerned the production of clothing (Camp, 3o). In general, however, the combination of these two statues kept women bound to the plantation.

Furthermore, the management of the plantations confined women even further. There were two main systems of control: gang and task. Under the gang system, time was at the forefront of planter’s minds because they were looking for ways to increase crop production (Camp, 20). Enslaved people would follow the sun and seasons by working from sunrise to sunset, with any breaks announced by bells or horns (Camp, 20). The other method of organization is called the task system and it is dictated by accomplishments rather than time (Camp, 28). Under both systems the threat of punishment was high. This led to enslaved people escaping to the woods for a bit of respite, and this could last anywhere from one night to multiple weeks (Camp, 48).

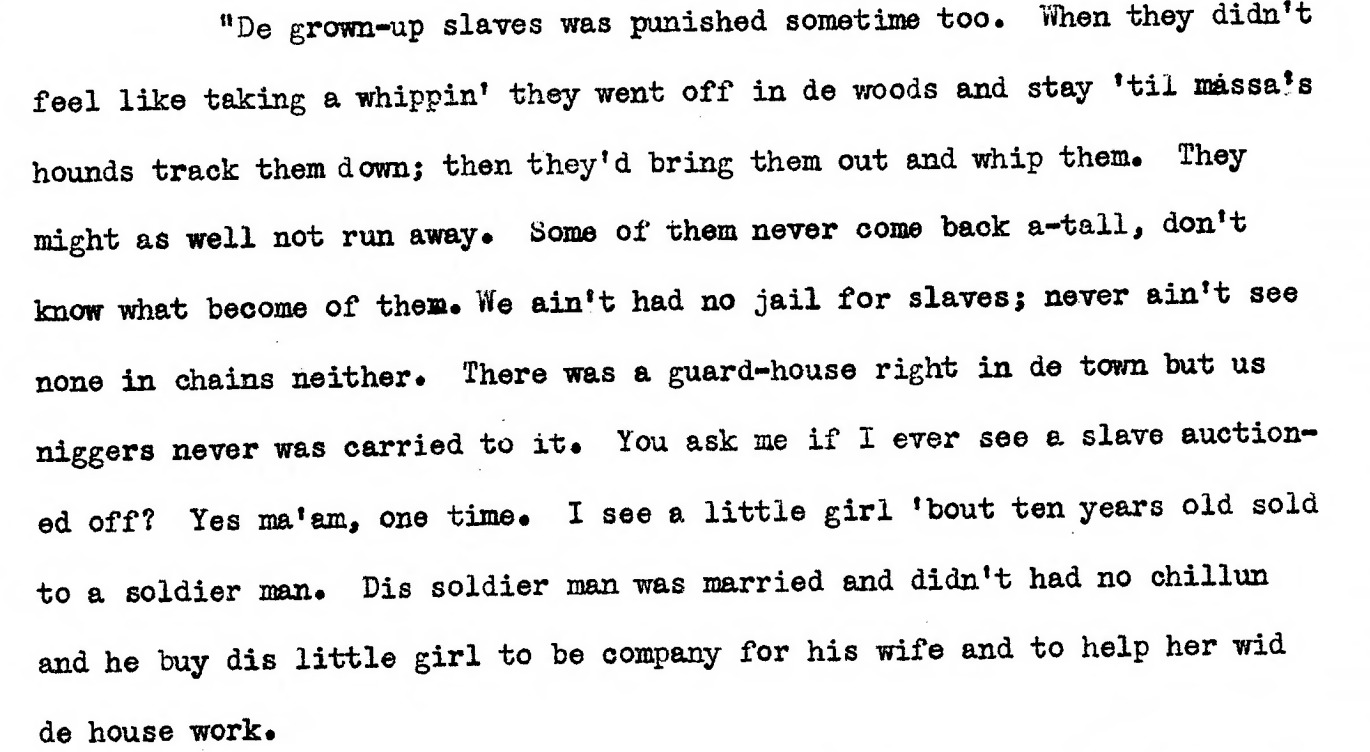

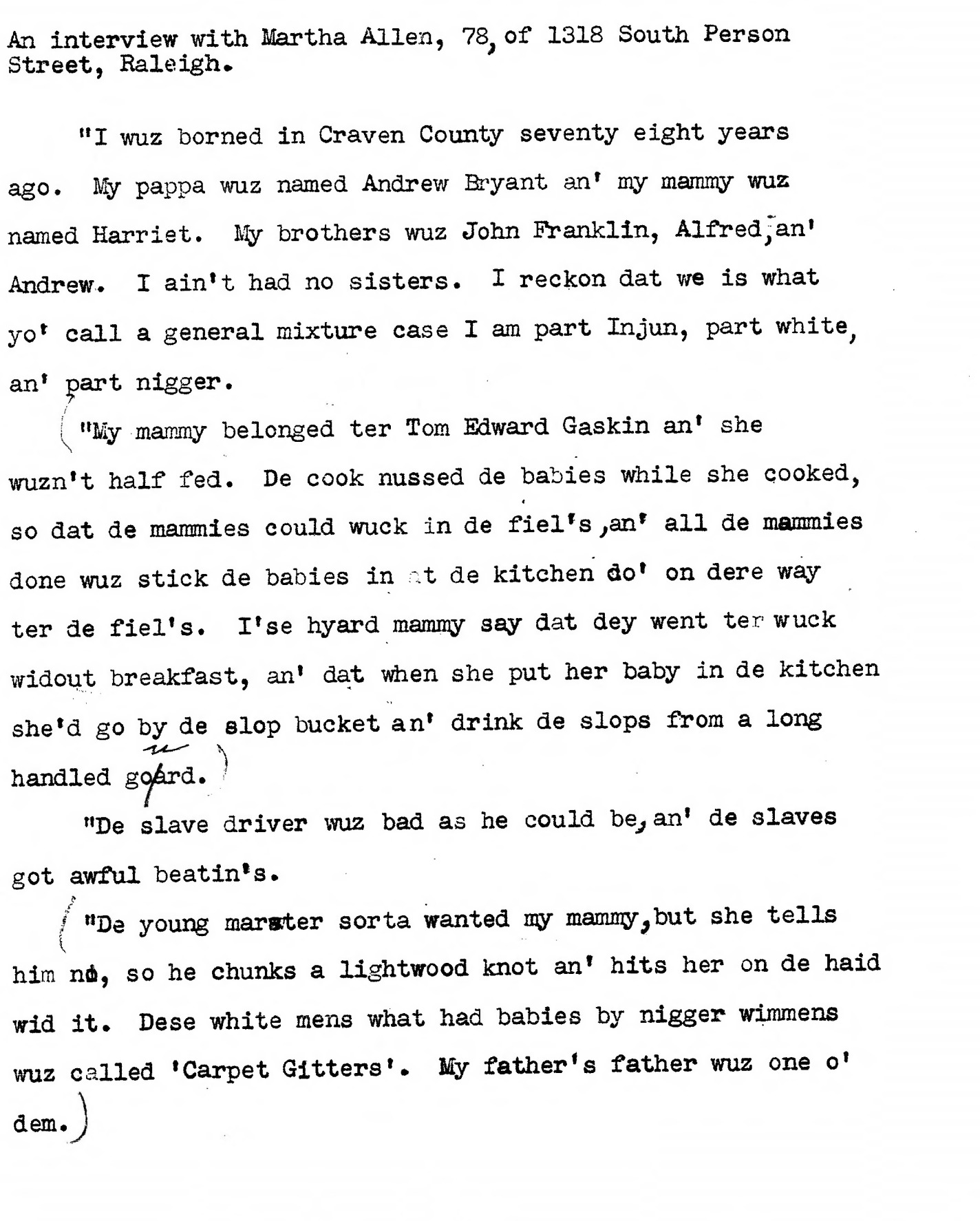

However, under both systems, women faced further constraints, for as soon as their fieldwork ended, they would have to begin their second shift in the home (Camp, 32). One enslaved woman recalled, “Women had to work all day in de fields an’ den come home an’ do de housework at night” (Camp, 32). Women’s household tasks included: cooking supper, cleaning the cabin, producing household goods such as soap and candles, washing and mending their families’ clothing, making clothing bed linens and bonnets, and textiles for general use on the plantation (Camp, 33). Unfortunately, this presented more opportunities for women to be punished. If women did not complete their second jobs to the liking of their owners, then they were brutally punished. On a plantation in Georgia, a woman failed to complete her spinning task which resulted in being stripped naked and her husband holding her arms as she was whipped 70 times (Camp, 33). This stripping showcases another level women dealt with that men did not; actions propelled by sexual undertones. It was not an uncommon occurrence for women to be forced to strip naked before receiving their whippings. As mentioned by Camp, “When women were physically punished, the violence directed against them was not infrequently laced with sexual overtones, the hint of sadism charged the atmosphere when women were stripped, tied down, and thrashed” (33). Furthermore, due to the sexual nature of many of the punishments received, it seems that women were whipped a disproportionate amount compared to their male counterparts. Charlie Hudson, an enslaved man, reported that he only ever saw his overseer whip women, “the man had whuppins all time saved up special for de’omans” (Camp, 33). Sexual possessiveness over enslaved women’s bodies led them to be on the receiving end of many violent acts. Furthermore, these acts occurred so frequently that enslaved people created words, like “Carpet Gitters,” “Suckers,” and “Vile Wretches” which described white men who seduced or raped enslaved women (Camp, 64).

Despite all the violence that enslaved women faced, they still were able to create moments of joy. In the woods surrounding the plantations, enslaved people would hold secret parties (Camp, 60). These were the few moments where enslaved women and men experienced true freedom pre-emancipation. At these parties, women would adorn elaborate dresses they made in secret (Camp, 80).

As stated by Camp, “The enormous amount of energy, time, and care that some bondwomen put into such luxuries as making and wearing fancy dresses and attending illicit parties indicate how important these activities were to them” (68). These dresses represented the one piece of self-expression of the enslaved in a society where they were constantly told who and what they were.

To summarize, women in the South were bound to their plantations due to their given roles; this made them more susceptible to violence from their owners which often held sexual undertones. In spite of this reality, enslaved women persisted and found ways to express who they were. Now that the foundation has been established, this allows us to see how this history played out.

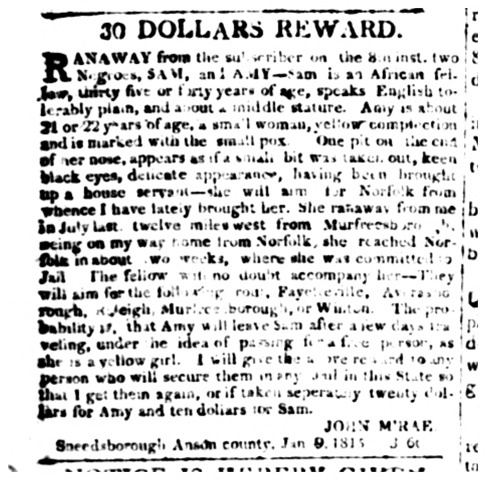

Although this notice is only a small square of a daily newspaper, much is revealed about Amy. Based on the inclusion of her age, John M’Rea revealed that she is of childbearing age. The addition of her having smallpox marks will aid in identifying her, but also points to the fact that she may not be as physically strong as other enslaved women. This is supported by M’Rea asserting that she has a delicate appearance due to her being brought up as a “house servant”. Since she would be in closer proximity to her white owners, this made her the perfect recipient of M’Rea’s romantic advances. Furthermore, since she was a delicate-appearing house servant, it would be very rare for her to leave the plantation, causing her to be unfamiliar with the surrounding geography. This is where Sam enters the picture. Sam likely acted as her guide to freedom, but they were not married. If the two had been spouses, M’Rea would have mentioned it to help with tracking where they might be headed. The missing piece on the end of her nose is mostly due to a past punishment from her previous escape attempt. Amy likely learned from her mistakes and ensured she reached freedom this time by seeking help from someone who knew the land. Amy’s reward is double Sam’s, and this is evidence of Amy’s importance to M’Rea. This importance may be due to what she contributes to the plantation as a household servant, but also what she provides to M’Rea in a sexual sense. Although Amy has attempted to escape, M’Rea shows his desperation for her return through her higher monetary value.

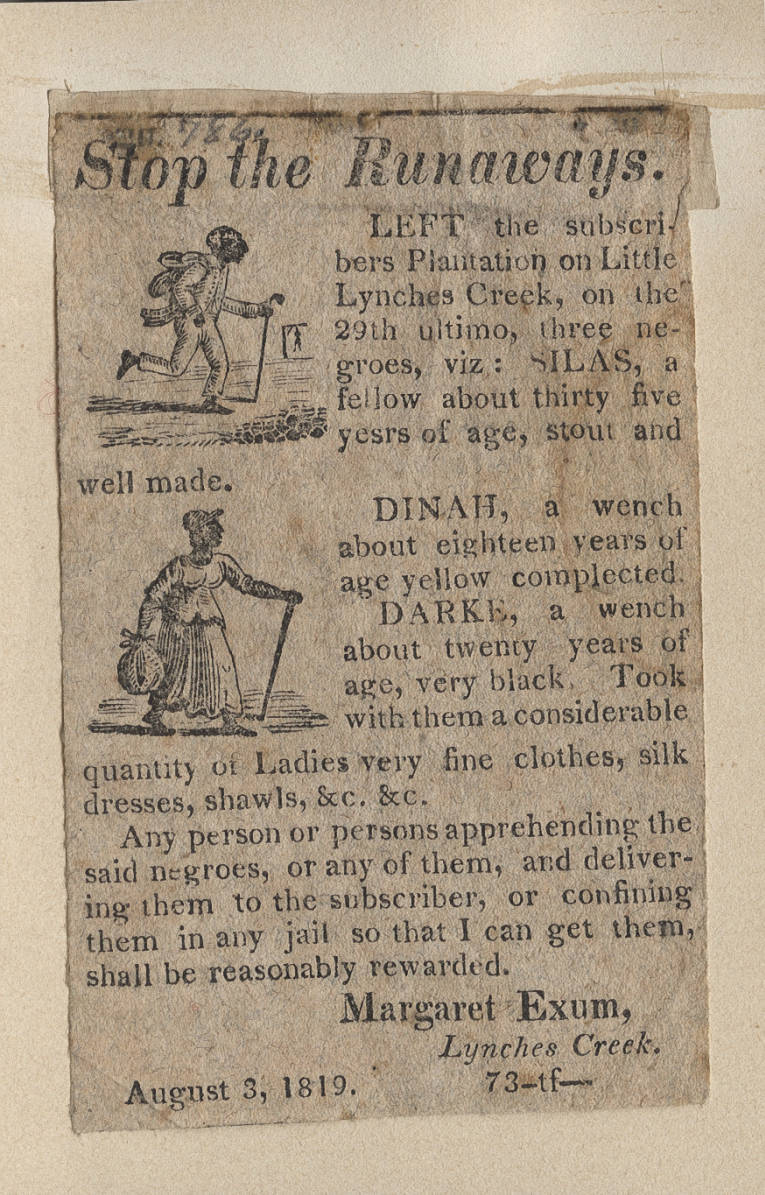

The description of Silas was brief and simply revealed what he looked like. However, the vagueness of his description makes it seem that his disappearance is not that significant to Margaret Exum because she did not include his height or complexion which is typically added to runaway ads. Dinah and Darke also did not receive many physical descriptors, but their complexions were included. Exum also included that they were “wenches” which signified that Dinah and Drake were able to have children (Berry, 17). This shows more effort on Exum’s part for their capture and return. Furthermore, Exum included the items they took with them: silk dresses and shawls. It would be unusual to see enslaved women with such high-quality garments, especially since these garments cannot be produced at home. Therefore, if Dinah and Drake tried to sell the dress or shawl in a nearby town, they would likely be captured. The lack of partners, children, and other family members indicates that Exum has little idea of where Silas, Dinah, and Drake are headed.

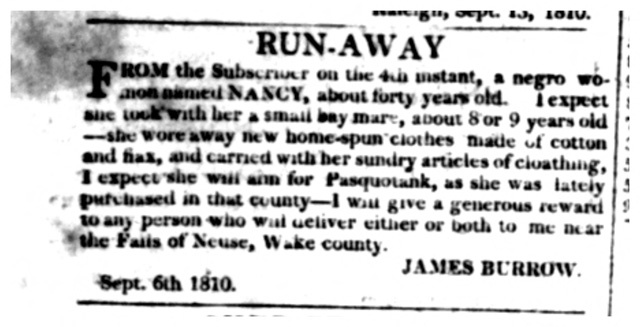

Nancy is an older woman who is most likely out of her reproductive years. This was deduced from her age and the word choice. Usually, if an older woman was able to give birth past the expected age range, they were referred to as “breeding wenches” (Berry, 17). The clothes she took were probably her prized possessions. These dresses were the only items that represented her as a person, so to Nancy, these items were priceless. The taking of the mare is evidence that Nancy has observed that horses allow for quicker movement, thus, it is fair to conclude that she is attempting to escape to the North. Although Nancy is no longer able to have children, she still is of importance to John Burrow because he offers a generous reward for her return and provides where she is likely headed. These details indicate that he is serious about her recapture.

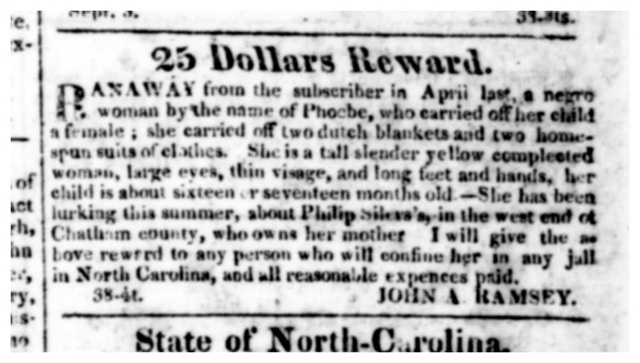

Phoebe brought along her young child which is evidence that this was an attempt at full flight rather than truancy. Bringing her child, especially a young one, presents a lot of risks for Phoebe since a child’s behavior is unpredictable. However, by not leaving her child behind, Phoebe is demonstrating a bond that prevented many mothers from fully fleeing (Berry, 17).

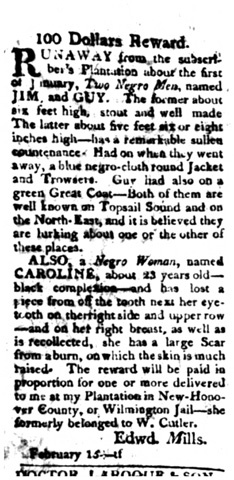

In this ad posted by Edward Mills, he is reporting the disappearance of three individuals: Jim, Guy, and Caroline. Jim and Guy are both given detailed descriptions, which would have made it easier to identify them. However, the descriptions given to Caroline are of a different theme than the men. Mills mentions her complexion and the scars she has. The scar she has on her right breast carries a sexual undertone. The normal attire worn by enslaved women covered their chests, so it seems that Caroline received this scar as a form of punishment. As mentioned in the historical account, often, when women in particular were punished, they were forced to strip naked. Furthermore, since Caroline’s chest would have normally been covered, one plausible reason for Mills knowing this scar exists is that he was the cause of her scars, he has taken advantage of her sexually, or both. It is possible (but highly unlikely) that the men do not have any scars to report which makes the inclusion of Caroline’s scars a point of suspicion.

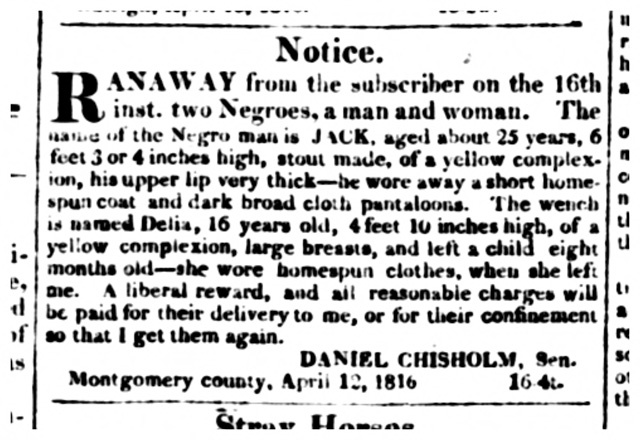

In the ad posted by Daniel Chisholm, he is asking for assistance for the return of Jack and Delia. Jack and Delia receive equal amounts of physical descriptors which, thus far, is not commonly seen. Although both are physically described, Delia’s descriptors carry sexual undertones. The inclusion of her large breasts is unusual because only one other ad mentions an enslaved woman’s breast, but in that case, its size is not mentioned. While it is unknown whether Chisholm was a “carpet gitters,” by using this word choice, he reduced Delia solely to her physical appearance. The relationship between Jack and Delia is unknown, but it is unlikely that they are married or siblings because Chisholm most likely would have mentioned it. Lastly, Chisholm reports that Delia leaves behind her eight-month-old child which may indicate that he is hoping that she will only commit truancy rather than full flight.

From the notices, a few patterns can be identified. Many of the women who fled were described as having a “yellow complexion.” and only Dinah and Caroline had black complexions. This may be due to darker women fearing they would not be able to blend in as free women which would limit the amount that tried to flee. Nancy and Phoebe are the only two women who did not travel with a male companion, and Nancy is the oldest at the age of 40. Although Phoebe's age is not mentioned, it can be assumed that she is older because all the younger women were accompanied by men, and this was likely due to the women not being familiar with the area surrounding the plantation. By the age of 40, Nancy probably would have had the opportunity to explore areas beyond her plantation. Furthermore, many of the women brought along handwoven clothing. This is reminiscent of what was mentioned by Stephanie Camp and the importance of dresses to enslaved women. Lastly, women typically seemed to be the victims of violence more so than men. In almost every notice, there is a mention of scars on the women’s bodies. This may be associated with the sexual undercurrents that often followed the description of the women.

Contained along the archival grain is where many enslaved women’s stories lie. It is up to us to look beyond what is told and focus on what is not. The exclusion and silencing of stories is where the true history lies. Enslaved women never stopped pursuing their versions of freedom, despite having all the odds against them.

Works Cited:

Berry, Daina R. The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation. Beacon P, 2017.

Camp, Stephanie M. Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. U of North Carolina P, 2005.