Coeducation at Dartmouth

Dartmouth was an all-male college that did not initially welcome women with open arms. Men used various tactics to intimidate and exclude women from having a joyous college experience. Fortunately, women persevered and continued to enroll.

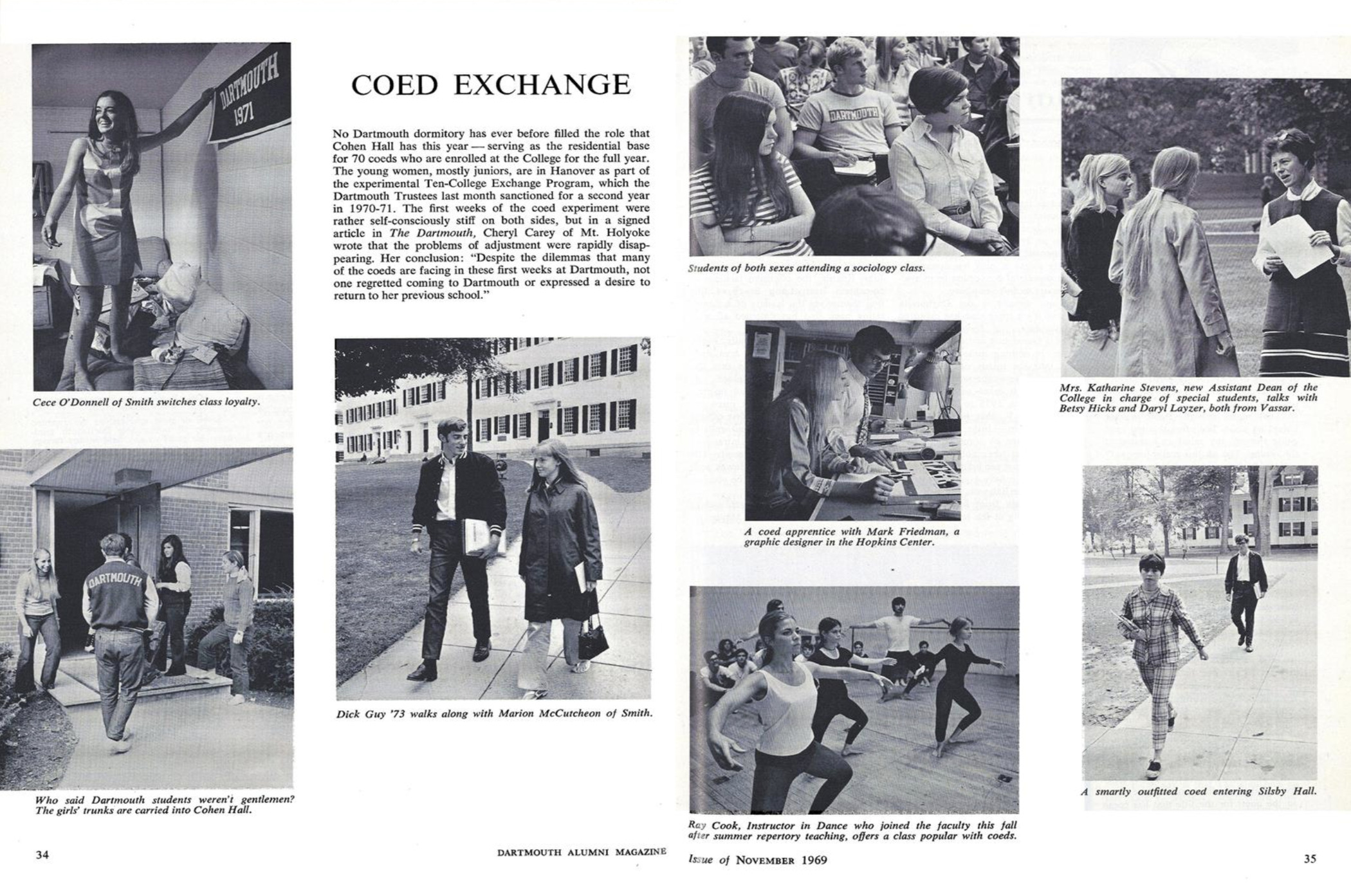

The first set of women Dartmouth accepted before coeducation arrived through an exchange program. It was a group of seven drama students in the 1968-1969 academic year who were not allowed to live in the dorms. Thibodeaux recalls seeing Meryl Streep: “I remember Meryl Streep. We were sitting in the student Center and Meryl Streep would pass by, and she was going to the drama department and because we were not co-ed we thought that was strange and unusual to be in that kind of environment.”

In the summer of 1973, Dartmouth executed its first experiment in bringing women to campus. The summer term was introduced to possibly accept women into the college without giving up a male seat. Around the same time, Harvard had two failed experiments to “give women access to non-credit lectures” states Nancy Malkiel in her book Keep the Damned Women Out: The Struggle for Coeducation.

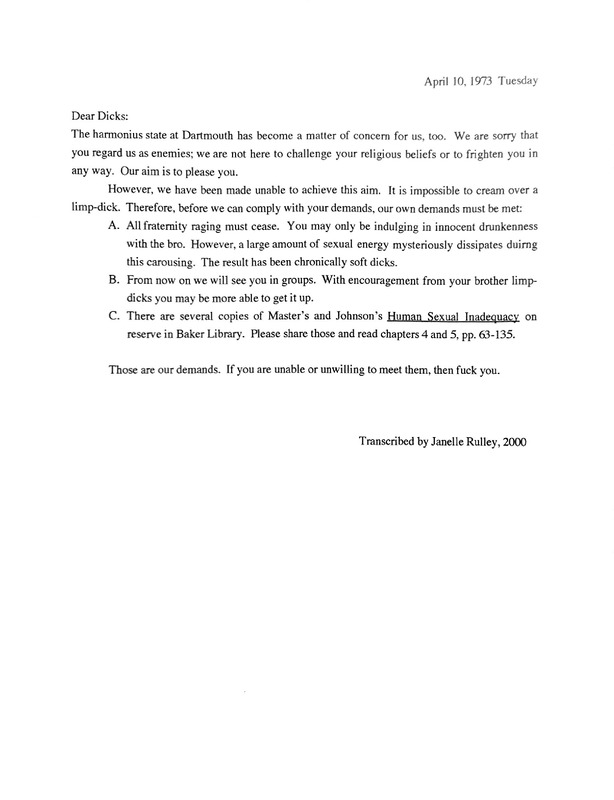

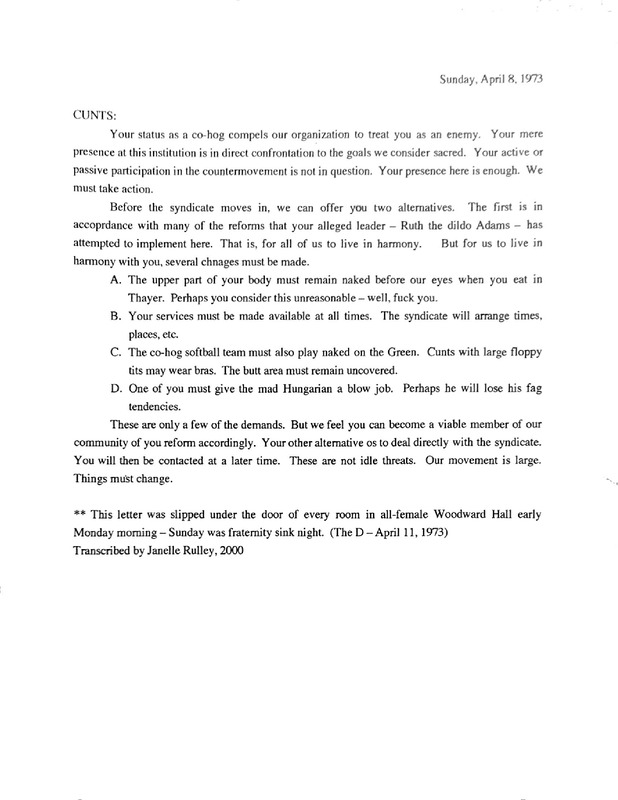

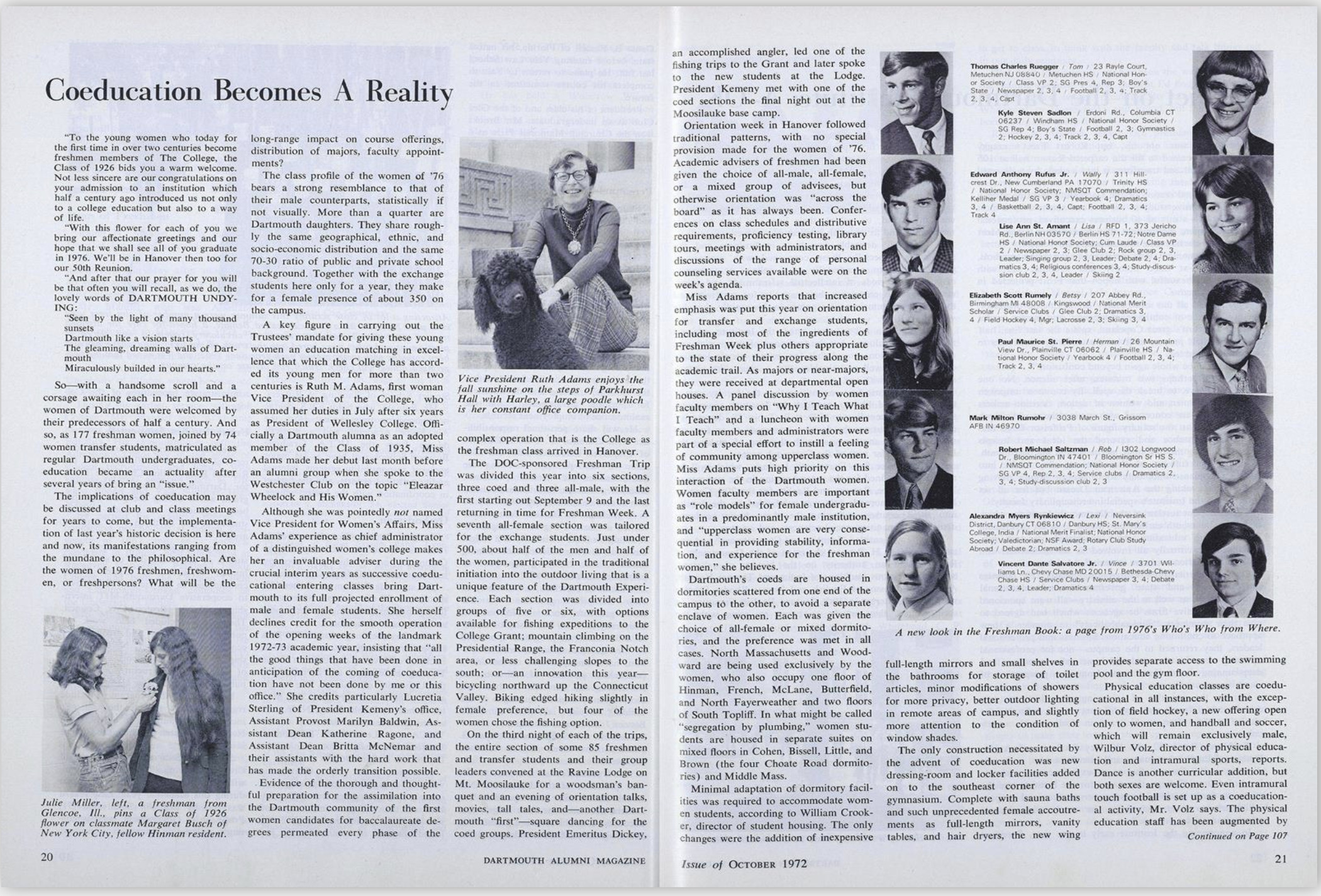

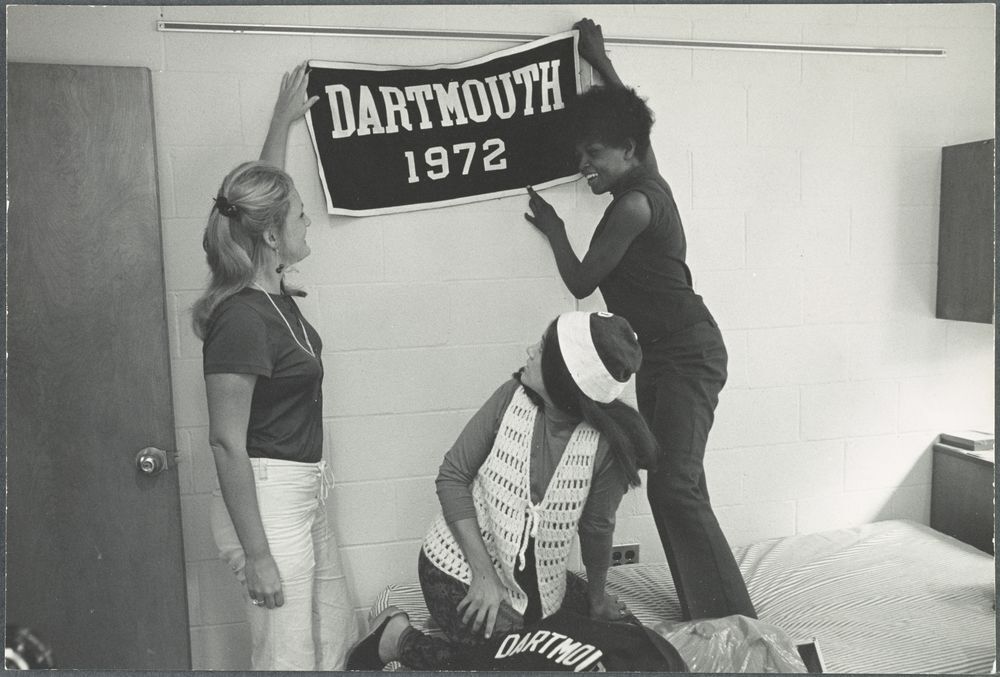

In 1968, the question of co-education shifted from should Dartmouth have coeducation to when and how should Dartmouth introduce women. As described in by Nancy Malkiel, Dartmouth hosted a co-ed week that brought almost one thousand women from eighteen different colleges. In 1972, Dartmouth officially became co-ed. Although many of the students were joyous, there were some who did not believe that women should be allowed at Dartmouth receiving the same education as they were. The anonymous "Cunts" letter was slipped under the doors of each room in Woodward Hall, a female dormitory. In response, the women wrote the "Dear Dicks" letter.

Male students called Dartmouth women “co-hogs,” an insult derived from the words "coed" and "quahog" which was a derogatory reference to female genitalia. Dartmouth received several letters from students and alumni that referred to Dartmouth women as “the enemy.” Nancy Malkiel notes that like Yale men, Dartmouth men also thought of women “simply as objects.”

In 1970, a survey of the Dartmouth community indicated that 83 percent of students, 91 percent of faculty and 62 percent of administrators favored coeducation. Thibodeaux describes his stance on coeducation as

“we were big supporters of coeducation not just because of the social enhancement ... We had known folks here on campus, so we were selfish because we wanted y’all on campus.”

Thibodeaux '71

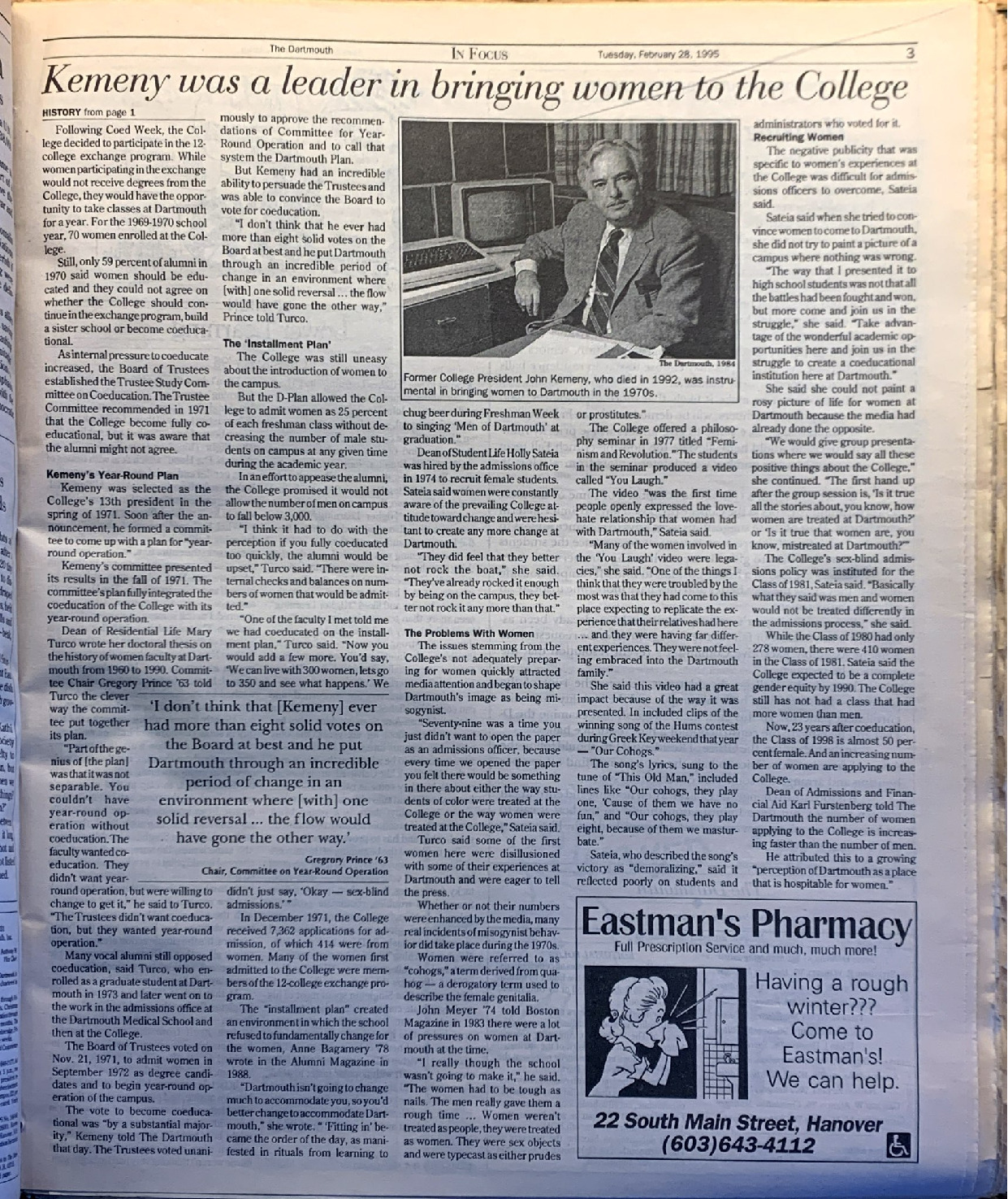

The article titled "Kemeny was a leader in bringing women on campus," describes some of the problems women faced. Women were treated as sex objects and faced challenges with inclusion. Given that some of the women who matriculated to Dartmouth were legacies, they expected to be embraced and have the same if not a better experience than their father did. Unfortunately, some of the men had a love-hate relationship with women being on campus.

With the ratio of men to women, there was rarely more than one woman in any given class. As a result, women were asked for the female perspective in the classroom. Most were uncomfortable in these situations, explained Malkiel. Women had mixed experiences with professors and were warned which classes to avoid. Amy Sabrin, a Dartmouth '72, stated that "some of the guys [told me] that the teacher was a misogynist, and he didn't think women could be serious artists, and I would never get a good grade — and they were right." Despite the setbacks, misogyny, and exclusion, women were not deterred and continued to receive their Dartmouth degrees.

“The most disrespected person in America is the black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the black woman. The most neglected person in America is the black woman” - Malcom X, 1962

The move towards coeducation led to the admission of Black women. In 1975, Black women made up 30 percent of the Black student population. Being a woman, specifically a Black woman, at Dartmouth has and currently is a struggle. Black women had to work hard and create safe spaces from micro-aggressions, feeling like an imposter, and being used as a test for acceptance into fraternities. According to Francille Rusan in Martha Biondi’s book Black Revolution on Campus, “We were these nice little Southern girls, who had probably even brought white gloves with us. This was a period where, literally, you started off as a colored girl and ended up four years later a black woman.”

The Dartmouth of fifty years ago is very different from Dartmouth now. The activism of Black students and the presence of women, especially Black women, aided the transformation of Dartmouth into the dynamic college it is today.

Previous: Conceding to Students Demands -- Next: To be Unapologetically Black