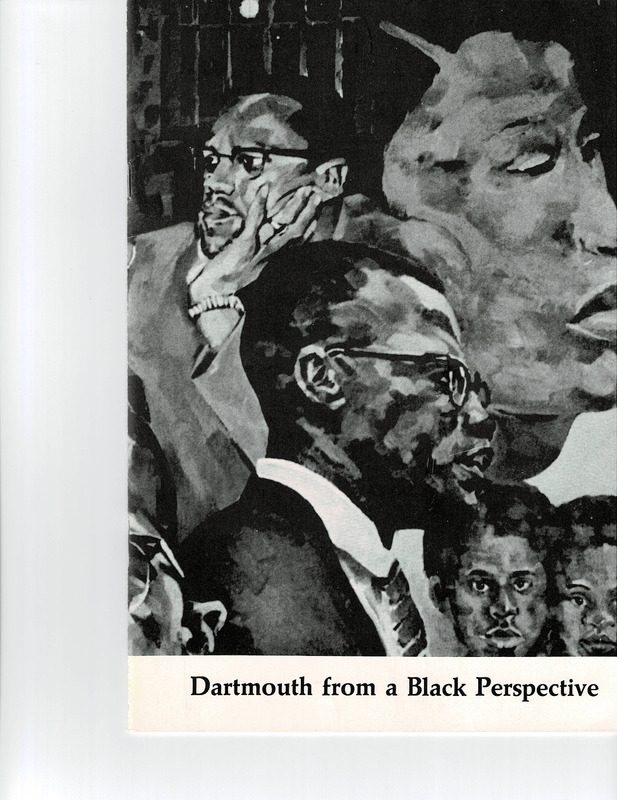

Tradition of Organizing in the Ivy League

Redding interviewed a dean for "Institutional Racism and Student Life at Dartmouth," a report she co-authored with Monica Hargrove and Eileen Cave. Redding recalled the dean saying,

“… how Dartmouth was very happy that when other of the Ivies that had sit-ins and walk-outs, unrest in and around race, Dartmouth never had. That they did not want any light shown if there were problems in that area.”

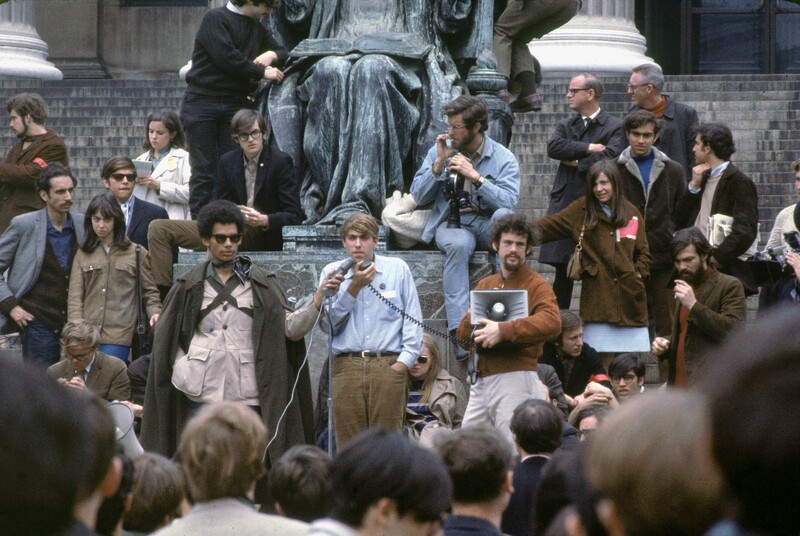

In Stefan Bradley’s article, "Black Power and the Big Green," he notes how “Dartmouth students benefited from the militant activism of peers at other Ivy institutions that sometimes involved building takeovers and the threat of violence (2, 2015).” For instance, what Columbia University students called “Gym Crow” sparked a cooperative rebellion from a diverse collection of college students and neighborhood residents. Once Morningside Heights, Inc., a group of landholding entities including Columbia University, Barnard, and the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, sought to “improve” and “secure” the Morningside Heights and Harlem neighborhood, the corporation planned a segregated gymnasium. This angered student activist groups, because

“the university already owned so much of the surrounding neighborhood, and now it was cutting a deal with the city to build a mostly private facility on land that by rights belonged to the public."

Meagan Day

Like Dartmouth, Columbia’s Black Student’s Afro-American Society (SAS) and the majority-white Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) occupied various university buildings in response. And it worked.

Black Identity, Equity, and Respect

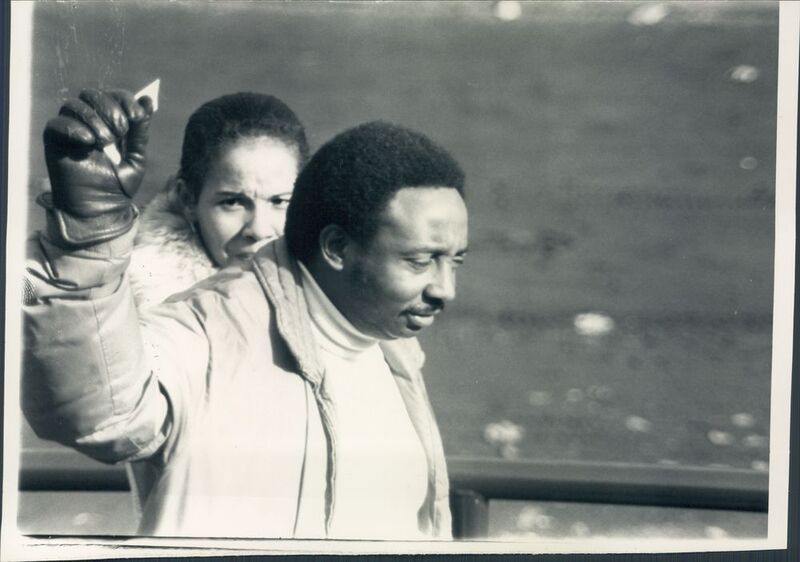

Up until 1945, only 120 African Americans had matriculated to Dartmouth (Bradley, 29). The inflammatory 1967 George Wallace visit to campus would introduce the "nation to [the fact] that there are Black students at Dartmouth College," recalls Wallace Ford '70.

When the former Alabama Governor stopped by Dartmouth for a presidential speech, students rocked his car back and forth until state troopers intervened. George Wallace attempted to depart campus after his speech, but a number of students, Black and white, joined in rocking his car back and forth. The group disbanded after state troopers intervened.

“… but there were a lot of us who were coming out of environments where we had not been cutting edge Black Power at all. And certainly among us, there were those who weren't even slightly interested in that. That they were coming to college to be serious students, and not get what some parents would say sidetracked with all of that. But then there were those among us that that was very central to what, for me, I wouldn't say it was Black Power, but I would say that it was Black identity, and equity, and respect.”

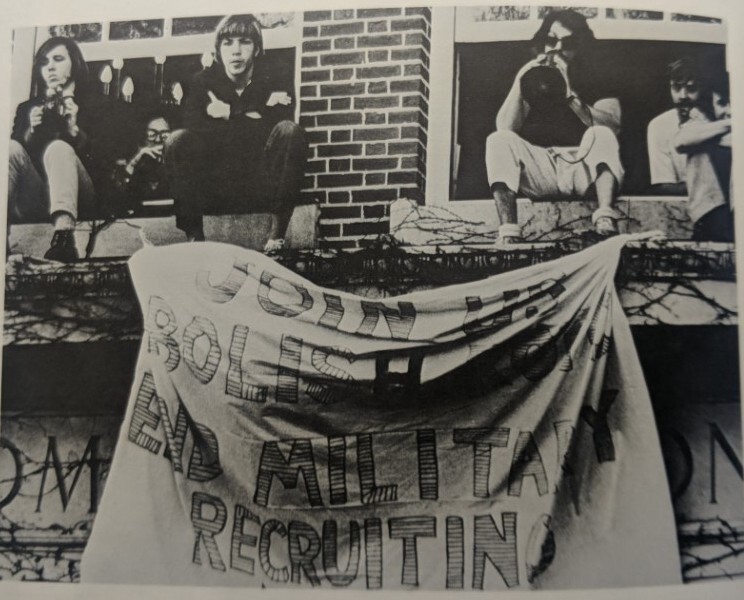

In 1969, Dartmouth students barricaded themselves in the Parkhurst Administration building to protest military recruitment on campus. Years later, on January 16, 1975, the Afro-American Society sent a letter to The Board of Trustees detailing their disapproval of the ROTC.

The Afro-Am society admitted the ROTC question “... deserves careful thought” and the “[B]lack student sentiment is split, just as is white student sentiment.” But because a great number of the Black student body viewed “the military as a historically racist institution,” the Afro-Am asked the Board of Trustees to “deny the return of ROTC to Dartmouth College.” The Afro-Am Society argued, “if Dartmouth were to support ROTC, we as a college would also be financially supporting a racist institution, the military.”

Years later, when JB Redding and her classmates Monica Hargrove and Eileen Cave would write the Redding Report, “they practiced Black student power, leveraging their status as students in institutions of higher education to act on behalf of the larger Black freedom movement” (Bradley 25, 2015).

Visit the next page to learn about the Redding Report and its impact on a personal and communal level.