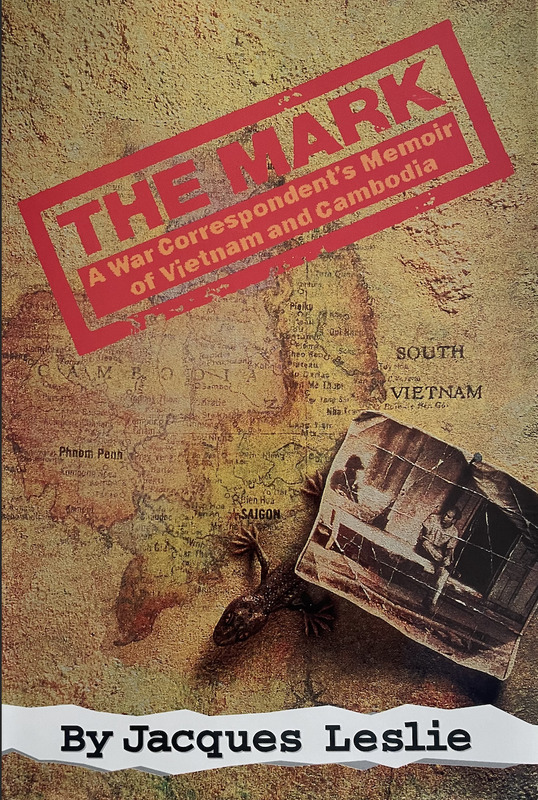

Jacques Leslie: An Overview and The Interview

Jacques Leslie was born in 1947 in Los Angeles, California to his father, who was a lawyer, and to his mother, a writer. Having inherited his parents' interests in politics and writing, he gravitated toward journalism at a young age. His passion for writing was reinforced at Yale University during 1964-1968, when he wrote for the Yale Daily News. At Yale, Leslie was inspired by many of his professors, and speakers who visited Yale and he ultimately decided to participate in a program called "Yale and China". There, he taught English at the Chinese University of Hong Kong between 1968 and 1970.

After joining the staff of the Los Angeles Times in late 1971, Leslie was sent to Saigon to train and prepare for work as a China correspondent. But he soon discovered that Vietnam was fascinating in its own right. Within a year of first arriving in Saigon Leslie found himself with “the mark”, or what he describes in the interview as the common experience of becoming obsessed with the war. Mr. Leslie attributes this obsession to the fact that:

"You couldn't see the most important things. It was 95% hidden. And, in a way, what I did there was to try to uncover some of those hidden things"

And indeed Jacques did catch “the mark” as he wrote countless stories about those "hidden things" such as the culture of local store ownership in Saigon, how Viet Cong villages operated, about political prisoners and even about the day he entered a Viet Cong territory himself. Leslie was ultimately expelled from Vietnam in July of 1973 after writing an article on South Vietnamese generals smuggling brass shell casings out of Vietnam. He then traveled and covered the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in 1975, as well as the political struggles in countries such as India, Spain, and China.

Today Mr. Leslie continues to write and tell stories, now focusing on environmental issues related to water usage and the effects of climate change on communities who depend on water resources.

Jacque Leslie's Work

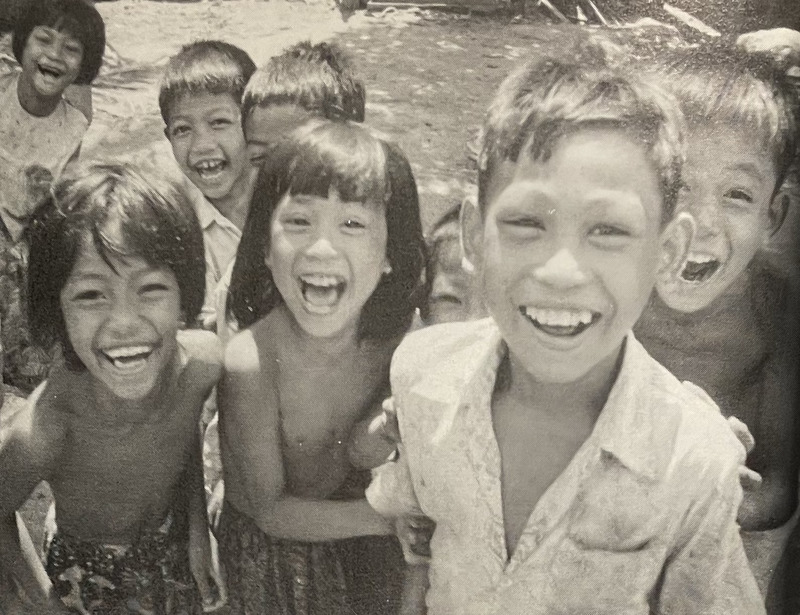

Jacque Leslie lived in Saigon and wrote pieces from Vietnam between 1972 and 1973. Leslie's first story from Vietnam focused on what it felt like to be in Saigon in the early 1970s and looked at the many deeper complexities of the city. In our interview, Leslie discussed how intrigued he was by the beggars in Saigon and how "they get control of their particular corner, because there was a way in which they were, as if someone had planned them where they would be spread out. And in a way that seemed to speak for something larger in Vietnam" (Leslie). It was the details and crevasses of culture and life in Vietnam, such as this, that powered Leslie's pieces and appetite to find interesting stories.

Throughout his time in Vietnam, Leslie became close with many other reporters and colleagues such as Ron Moreau, Véronique Decoudu and Nick Proffitt. With them, Leslie traveled across South Vietnam writing about political corruption and military violations on both sides of the war. Leslie even went with Decoudu to a Viet Cong territory in the second or third day of the Paris Peace Accords ceasefire in 1973. This visit gave Leslie a whole new perspective on the communists and the inner-functioning of an NLF territory and those who lived there.

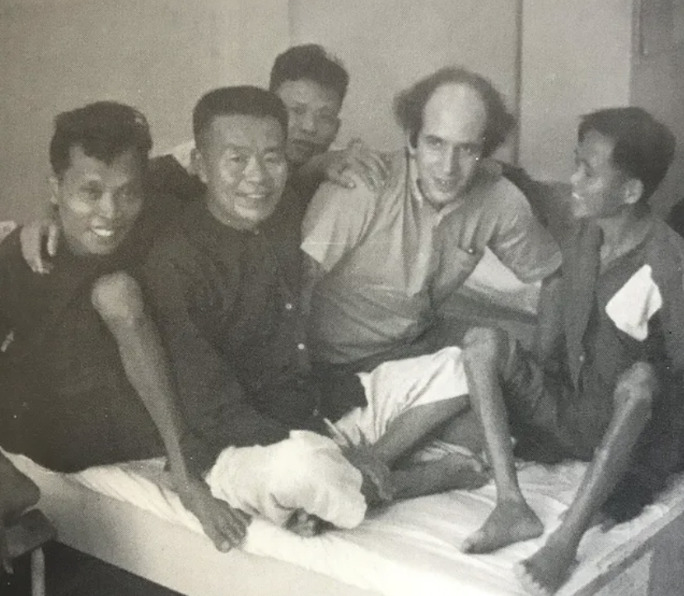

From these stories, Leslie began meeting sources and other journalists which opened doors to new experiences of war which only provided him with more content to write from. In both his memoir and our interview, Leslie mentions the stories he wrote on his experience of meeting with Con Son's "tiger cage" prisoners. Leslie and journalist, Martin Woollacott, were smuggled into a province hospital in Quang Ngai, in which 13 recently released prisoners were being treated for their malnutrition and atrophied bodies, speaking about the abuse and violence they endured for years while being captive by South Vietnamese forces. In the interview, Leslie specifically mentions a poem the prisoners handed him, a poem they wrote in salute to another prisoner who was tortured and has passed in the prison, "And the last line was, 'we wish you could be here to share your joy with us.' That still gets me" (Leslie).

Leslie's experiences, while makings for highly engaging journalistic writing, carry the burden of witnessing the horrors of war and the difficult decision making required of war-time reportage. This was especially the case when Leslie was was in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge's takover in 1975. In his memoir and in our interview, Leslie reflects on witnessing the last days of the last Khmer Republic defense army outpost that overlooked the Cambodian landscape. To Leslie, the knowledge that the Khmer Rouge had taken over most of Cambodia at that point, and was inevitably coming for that Khmer National Armed Forces (FANK) outpost had driven the Cambodian soldiers mad. Leslie described them as having, "more or less lost their minds. They, they made no sense. They didn't know what they were doing. There was no government giving them any instructions. The comander seemed bewildered. And it seemed surreal. And very sad". Jacques, while reflecting on these highly emotional moments during his time in Cambodia, also discusses "one of the biggest regrets really of [his] life". As a result of the increasing violence from the Khmer Rouge takover, the United States issued a military evacuation, in which soldiers and reporters, such as Jacques, would be evacuated from Cambodia. At that point Jacques offered to evacuate his Cambodian interpreter and his family, but ultimately discouraged his interpreter from leaving Cambodia since the transition to American way of life might be too difficult. Ultimately, Leslie's interpreter was killed by the Khmer Rouge and his suggestion to remain in Cambodia remains one of Leslie's heaviest burdens from the war.

In the end of our interview, Jacques reflects on coming home and openly aknowledges his struggle with depression following the war. He brings up the questions he had such as "What do you do with your life" after returning home from witnessesing and writing about some of the most complex, riveting, and emotional aspects of the Vietnam War.