The Rise of Resistance to ROTC

How did sentiments concerning ROTC manifest on Dartmouth's campus?

Due to the growing controversy over the Vietnam War, a corresponding skepticism of ROTC became prevalent in the United States and on Dartmouth's campus. More information began coming back from Vietnam in the form of video recordings on the nightly news, death tolls, and “alternative media” as Peter C. Sorlien ’71 would call it. By early 1968, small student antiwar protests had begun, only to grow in number as time went on.

Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

The history of ROTC and Vietnam antiwar movements on Dartmouth’s campus is often over-shadowed by the Parkhurst Hall Occupation on May 6th of 1969, where over 50 demonstrators “seized and occupied Parkhurst Hall for 12 hours” (LeMaistre, The Dartmouth, May 7, 1969). The protestors occupied the building and forced Dartmouth faculty and administration out of the building in the name of abolishing ROTC on the College’s campus, leading to 56 student arrests at the hands of New Hampshire State Police. Headlines “Anti-ROTC Dissidents Seize Parkhurst Hall, Yield to 90 State Troopers After 12 Hours,” and “Demonstrators Eject Deans from Building" covered the front of The Dartmouth newspaper, and the story made national news. However, in order to understand the gravity of this event, we must add the events that took place before it to the scope of the seizure of Parkhurst Hall and the consequences that occurred after it.

ROTC, Related to the Draft

In Dean Thaddeus Seymour’s DVP interview, he reflected on this period of heightened tensions, characterized by protests against the war in Vietnam and ROTC on campus. As the Dean of Students from 1954 to 1969, he described the ubiquity of these protests on campus, stating that “I think an honest answer [is that] it was just one more damn thing to worry about.” He explained how the Armed Forces Day protest became an issue, as it was akin in size to the Winter “Carnival Statue; there’s just no way to avoid that." He stated that from about 1966 on, each Armed Forces Day, “to me [chuckles] was trouble.”

Eventually, Dean Seymour dove into the personal aspects of the protests, the students’ practices during the time and their reasoning to why. He mentions, “Pretty soon you had students going to Canada. I have a number of students I’m still in touch with who went to Canada rather than be drafted. A lot of people called them cowards, but increasingly [chuckles] I think—people said, ‘Boy, those guys were smart.’ As being drafted meant going to Vietnam, it became very different.” He notes how the sentiment became different as Dartmouth progressed into the mid to late-1960s, as the war casualty numbers became realer and larger, as people that had participated in Dartmouth ROTC actually were deployed to Vietnam. “If you were a college student in good standing, you were deferred and hoping to God the thing would be over before you ended up being drafted. Well, there were two aspects of it: (a) If you were a college student you were deferred, and I believe if you were a graduate student you were deferred.”

As evident in Seymour’s interview, the draft not only became a prevalent topic in the minds of Dartmouth men in the 1960s, but it became a primary issue in which, as time went on, came to mean life or death. As the fear and resentment for the draft became existential at this period of time, the actions of Dartmouth students became practices in the effort to survive. Thus, when we talk about the antiwar and Anti-ROTC protests at the time, we must keep in mind what was at stake for the students participating in the protests themselves.

Because a majority of Dartmouth students at the time were eligible for the draft, the antiwar and anti-ROTC movements were inherently anti-draft too. It was the protestors themselves at the highest risk of going to Vietnam, so we see the protestors themselves being the most involved. Moreover, we see the great lengths at which activists would go to get their message across. When we begin to conceptualize the protests in this fashion, we can see how going to jail for occupying and forcing administration out of Parkhurst Hall is not so extreme in comparison to being shipped off to Vietnam to have a decent chance of either dying or coming home with severe PTSD.

Case Study: Peter C. Sorlien '71

When Peter C. Sorlien arrived on Dartmouth’s campus as a student for the first time in the fall of 1967, he described that he “was real green when I when I arrived here. I was a very naive kid, not much view of the world.” He was following in the footsteps of his father (Kenneth E. Sorlien ’43) and his brother (Cai E. Sorlien ’67) in coming to Dartmouth, excited about the outdoors. In keeping with following the footsteps of his brother, Peter joined Army ROTC, of which Cai had a scholarship for his four years at Dartmouth. On his first term in ROTC, he said, “it was kind of boring. It was very civil. There were classes that went with it. And the classes were pretty simple. But it was all about military discipline… this was neither very stimulating, not very challenging and actually, to be truthful, just sort of not very interesting. But it’s what my brother did. It’s what was the honorable thing to do.”

"It was a hot topic all over campus. Yeah, I mean, it's on everybody's mind. And my brother’s over there. So why is my brother there? Why is his life at risk?"

This idea of the honorable thing to do became a a blurred concept in his second term on campus, the winter of 1968. His brother had been deployed for Vietnam in late 1967, and as a self-proclaimed history buff, he began to discover the deeper details about what was going on in Vietnam. “At that time, there was an English professor named Jonathan Mirsky here, who was very familiar with that part of the world, with that culture,” Sorlien said. “And he knew a lot more about what was going on. And so he was beginning to tell the truth. Then I was also directed to other alternatives-- the alternative media, not the mainstream media, but the media that was also doing much more investigative journalism.” He began to read into the theories being used to justify American intervention in Vietnam, namely the Domino Theory, where he said “western democracies are in a pitched battle with communism. Additionally, he credited Dwight D. Eisenhower’s coined “military industrial complex” from his 1961 Farewell Address as another reason for protesting the war in Vietnam.

“I concluded that the war in Vietnam was just the latest iteration of the military industrial complex, finding a place to have its products destroyed, so that we would spend the money to remake them. That, we had a large military, we'd had a large military for the Cold War. We built up this enormous nuclear deterrence and other aspects of this really large military as part of the Cold War opposition to the communists, and the war in Vietnam was just an extension of that. But it didn't do any good to just stockpile weapons, you had to destroy them. In order to make money by making more.”

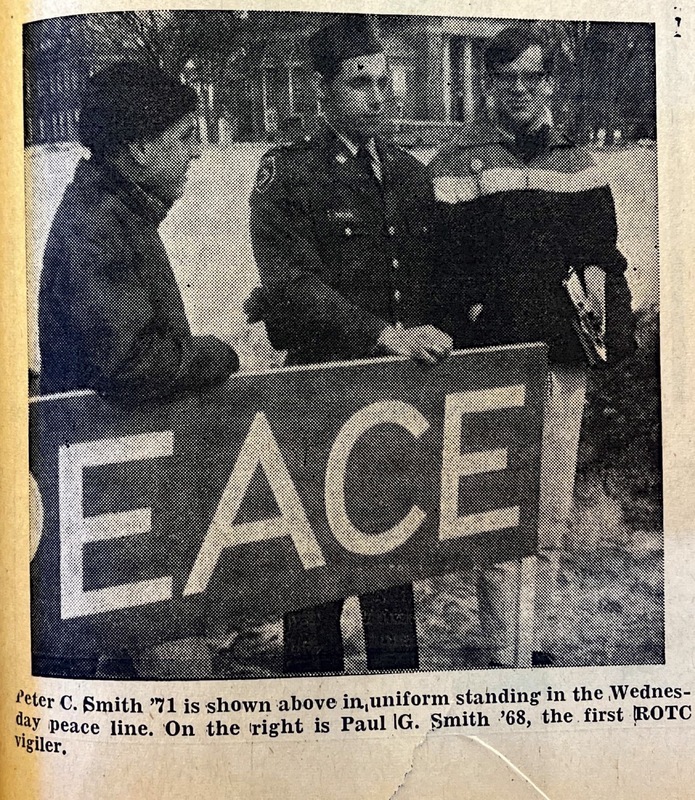

Sorlien joined a weekly protest in early 1968, participating in a peace vigil that took place on the west side of the green at noon on Wednesdays. “Somebody had just made up a sign, it was waist high and about four feet long. Blue with white lettering that said ‘Peace.’ And, and we stood there in silence, Wednesdays at noon.”

A Tale of Three Protests

On Wednesday, February 21, 1968, Dartmouth senior and Army ROTC cadet sergeant Paul G. Smith ’68 stood in full dress uniform during the Wednesday peace vigil on the green, with the reasoning “I disagree violently with the war, and I feel that I have the right to express this opinion, not only as an individual, but also as a Reserve Officers Training Corps student.”

The next day, an article was published in The Dartmouth, reporting his protest and including a quote from Colonel William L. Nungesser, commanding officer of Army ROTC at the College: “It is a violation… The regulation states that the uniform will not be worn at any picket or demonstration which is not sponsored by the United States government”. The following Monday, The ROTC office published the rules regarding the participation in public demonstrations. Participation when in uniform was forbidden.

The subsequent Wednesday following Smith’s protest, Peter Sorlien stood in ROTC uniform during the Wednesday peace vigil on the green, attracting attention from The Dartmouth and Dartmouth’s ROTC program. As Paul Smith had a scholarship to protect, Sorlien said that “I came in uniform, because [Paul] couldn’t… this was a deliberate slap in the face, because ROTC had informed us all that you cannot do this. And I looked at it and said, “I've got to resign from this organization. How can I make this meaningful?”

Sorlien’s protest made the front page of The Dartmouth the next day, and the next week, he was dismissed from the ROTC program at Dartmouth. In his newspaper interview, he explained, “ROTC is totally antithetical to everything Dartmouth stands for… namely, academic freedom, freedom of speech, and individual responsibility… There is no searching for the truth in the Army. Everything is sent down from higher up”. Sorlien’s sentiment was echoed throughout antiwar and Anti-ROTC protests at Dartmouth in 1968 on, exemplified by signs such as that atop this page, championing “OBEY, OBEY, OBEY” and “ROTC DOES NOT BELONG ON A LIBERAL ARTS CAMPUS.” Additionally, satirical cartoons with Anti-ROTC agendas like that of the one above appeared in The Dartmouth. Sorlien went abroad to France and Germany for most of 1969, and when he arrived back on Dartmouth’s campus in the winter of 1970, many of his friends had been arrested and some expelled during the Parkhurst Hall Seizure of May, 1969. As the decision to phase out ROTC and complete the ban in 1973 had been voted upon and decided in 1969, many of the protests Sorlien was heavily involved in were now smaller or had fizzled out. As he said, “ROTC was still here, but by that time, the tide of public opinion had turned on the war as well.” In 1969, Peter's brother Cai returned home to the United States with severe PTSD, taking years before reconnecting with his brother.

The recording and transcript of the DVP interview with Peter Sorlien '71 can be found on the Our Interviews page.