The Draft

On December 1, 1969 the Selective Service System held a draft lottery for the first time since the second world war. All of our narrators witnessed and experienced the lottery first hand as college students themselves surrounded by peers who were eligible for conscription.

“Wherever you went everyone would be asking: what's your number?”

- Joan Rachlin

"It was just surreal to think that this really potentially life changing, incredibly consequential turn in your life was going to be decided by pulling a ping pong ball out of a barrel or whatever it was. Surreal." – Dennis P. Bidwell '71

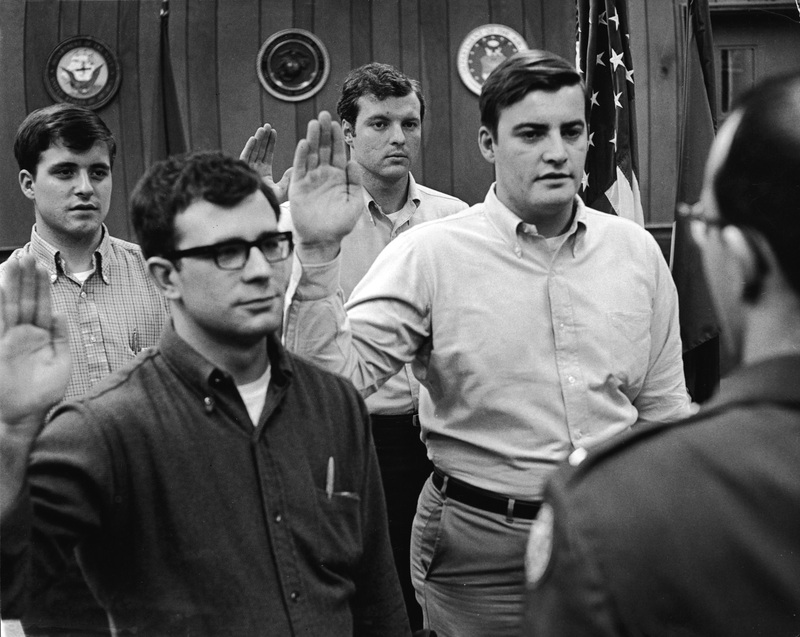

After World War II, President Harry Truman successfully advocated for the extension of the Selective Service Act throughout the so-called "peacetime" of the late 1940s. In 1951, the act was reauthorized mandating that all males aged 18-26 register for the draft within thirty days of their eighteenth birthday. The continuation of the draft system was partly due to the escalation of the Korean War and the fear that the United States military would not have consistent personnel to maintain its global presence and commitments to the Republic of Korea.

The continuation of the “peacetime” draft system allowed for Lyndon B. Johnson to simply increase monthly draft calls at the start of the Vietnam War rather than re-implement the entire draft system. However, the selection process under the existing draft system was criticized for its perceived biases. Local draft boards, predominantly composed of military veterans, possessed significant discretionary power in granting exemptions, deferments, or favoring certain individuals. Those called up for service were often from lower-class backgrounds, with a notable underrepresentation of college-educated individuals. The disparities in local draft boards’ decisions are highlighted by the disproportionate number of African Americans serving in Vietnam. Despite constituting 11 percent of the U.S. population, African Americans accounted for 16.3 percent of all draftees and 23 percent of combat troops in 1967.

"I don't know anyone who wanted to be drafted because if you wanted to be drafted, you would have gone into ROTC." – Joan Rachlin

By the late 1960s, uncertainty regarding U.S. involvement in Vietnam grew on a national scale. In conjunction with claims of unfairness in the draft selection process, opposition to the draft skyrocketed. Young people around the country were unwilling to fight in a war they did not believe in. President Johnson sought to address this discontent by revising the Selective Service Act. The revised act implemented a national lottery system, which aimed to centralize the draft process and reduce the influence of local draft boards. Under this system, each individual's birthdate had an equal chance of being chosen. 336 capsules, representing each day of the year (including leap year), were placed into a glass cylinder. The first birthdate drawn would be assigned the number one, indicating the highest likelihood of being called up, while subsequent birth dates were assigned numbers 2 to 366. The lower the number, the less likely you were to be called up.

"you would hear literal screams of either joy or profanity as people [had their birthdays called]" – Joan Rachlin

On December 1, 1969, the nation watched as the fates of thousands of young men were determined through the draft lottery on live national television. On Dartmouth’s campus, men gathered together in fraternities and dorms anxiously awaiting to hear when their birth date would be called. At the time, deferments were granted for education, primarily leaving graduating seniors at risk of being drafted. Nevertheless, the impact of the lottery spectacle was palpable on campus.

"...no one I knew that had a low number was happy. Not anyone was even close to sane after they got a low number. They were all really off the rails for a while figuring out what to do." – Joan Rachlin

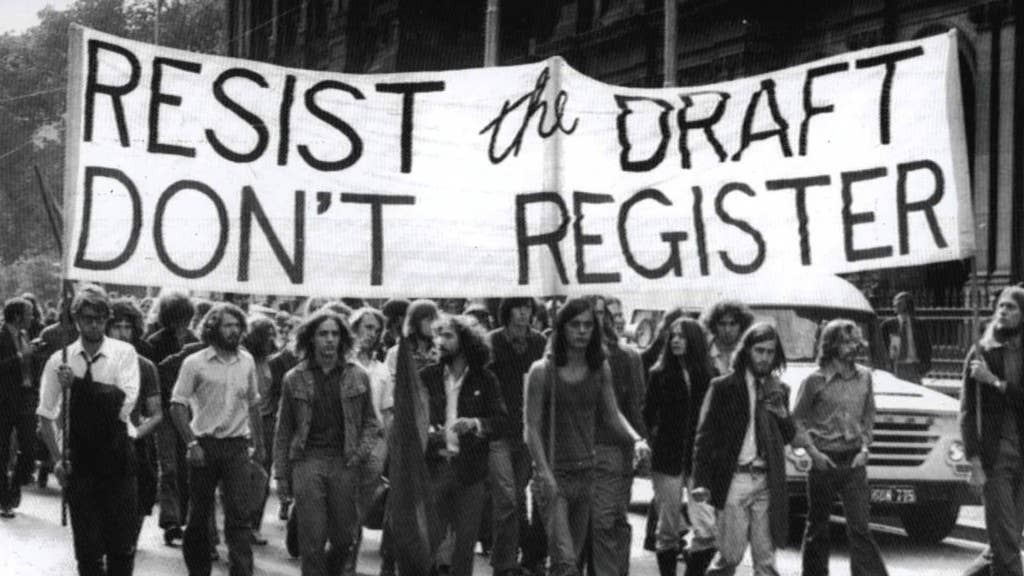

Draft Evasion

With thousands of men primed to go to Vietnam, many turned to creative methods to get out of being drafted. Charlotte Albright spoke about the different ways the people she knew got out of being drafted.

Many wealthy families were able to cheat the draft system.

“A lot of his friends were getting somehow bought out. Or they were paying doctors to say things. I mean, there was a lot of scamming of the system.” – Charlotte Albright

Other people who were also wealthy, emmigrated to Canada or other countries. Many of the people Charlotte knew from working in theater were gay and the Army would not take them.

"They showed up and, you know, really provocative outfits for their draft physical. I remember one, the lighting designer at Williams, a guy named Santo Loquasto. I never learned exactly what his underpants look like. But I know that he bought something that got him out of the draft can't tell you what it was. But there was some pretty amazing tricks that people tried to have the draft board say no, and theater people were pretty good at it. " – Charlotte Albright

Charlotte highlighted the inherent socio-economic disadvantages many people had if they were trying to get out of being drafted.

“My other friends, you know, my high school friends from Hollidaysburg, and Altoona, Pennsylvania, they didn't have that kind of money. They didn't have those doctors. They came from more conservative families. They left and some of them didn't come back. So that kind of bothered me.” – Charlotte Albright

Dennis P. Bidwell '71, who was a Conscientious Objector, also acknowledged the privilege that helped him achieve CO status and the guilt that came with it:

"The sense of guit set in. It still is with me [...] Look at the resources that I had access to at Dartmouth College to guide me through this process! What an incredible privilege that most folks didn't have! So somewhere along the way, this seed got planted and never really left me that some poor Black kid from Jersey City was going in my place, who didn't have the options that I did, who may or may not have come back. That's a part of all this. It’s that I got my CO status, in large part, because of my privilege and access to expertise and information." - Dennis Bidwell

By the time the US Millitary became entirely volunteer-based in 1973, hundreds of thousands of men had found ways, legal or illegal, to evade being drafted. Because of such a large number of draft dodgers, President Jimmy Carter pardoned everyone and allowed those who left the United States to avoid being drafted to return without any punishment.