Continuing Presence in Washington: Dartmouth's Lobbying Machine

Some Dartmouth students felt that the large political demonstrations and marches that sprawled over the front pages of newspapers were ineffective in real political change. In his oral history interview, Dennis Bidwell ’71 shared that “I also agreed with the sort of fundamental concept […] that massive protests really haven’t moved the needle that much in terms of administration policy, or congressional votes.”

This desire for more direct political action was shared by Dennis Sullivan, a professor in the Government department. While the 1970 student strike was being organized, Sullivan noted that certain strategies of student activism could rally larger, widespread political effort (Masselli ’70 and Rockwell ’70 n.d.). Later, on May 4th, 1970, alongside College senior Eric Martinez ’70, he chartered “Continuing Presence in Washington,” or CPW, a lobbying effort that would propel members the Dartmouth community into the offices of Representatives and Senators for months.

Per an internal document, CPW was founded on four core beliefs:

- The President’s invasion of Cambodia clearly demonstrated that he no longer deserves the trust, indeed the support, of the Congress and the public.

- Nixon’s action, and the manner in which he acted, moves him out of the “middle ground” of public opinion on the war, and hence opens up the possibility of effective political action.

- One-day peace marches in Washington and elsewhere evoke greater reaction from the press than from the Congress.

- We muse concentrate all of our efforts on the issue of Indochina. We admit that there are other issues demanding action, but we feel that we must single out that issue which appears most successfully opposed, and pursue that goal with all our energies.

More succinctly, CPW existed to “bring about the withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Southeast Asia.” Volunteers connected students, faculty, and other Dartmouth community members with lobbying opportunities in Washington, as well as transportation and housing. They also prepared the visitors to be effective lobbyists, even if they were political amateurs. This work was split between two physical offices, with one in Hanover and another in Washington. This page explores the inner workings of CPW, the Dartmouth and external resources that made such an effort possible, and the impact CPW had on the anti-war movement.

From Amateurs to Lobbyists: Preparing Citizens to Influence their Congressmen

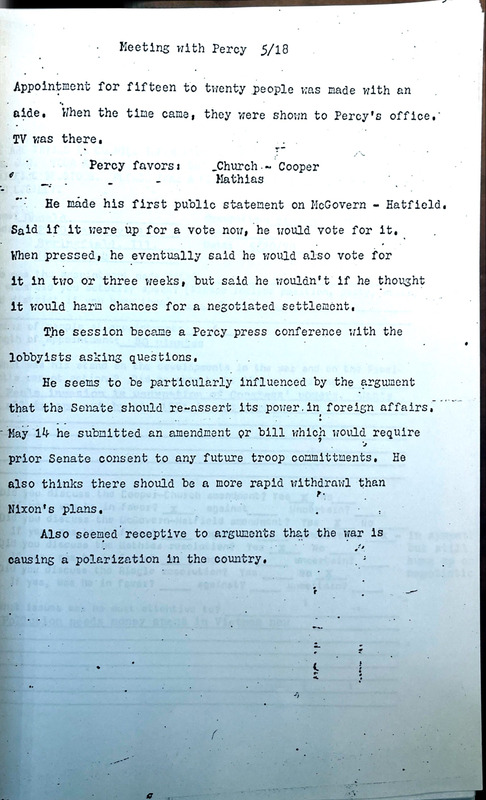

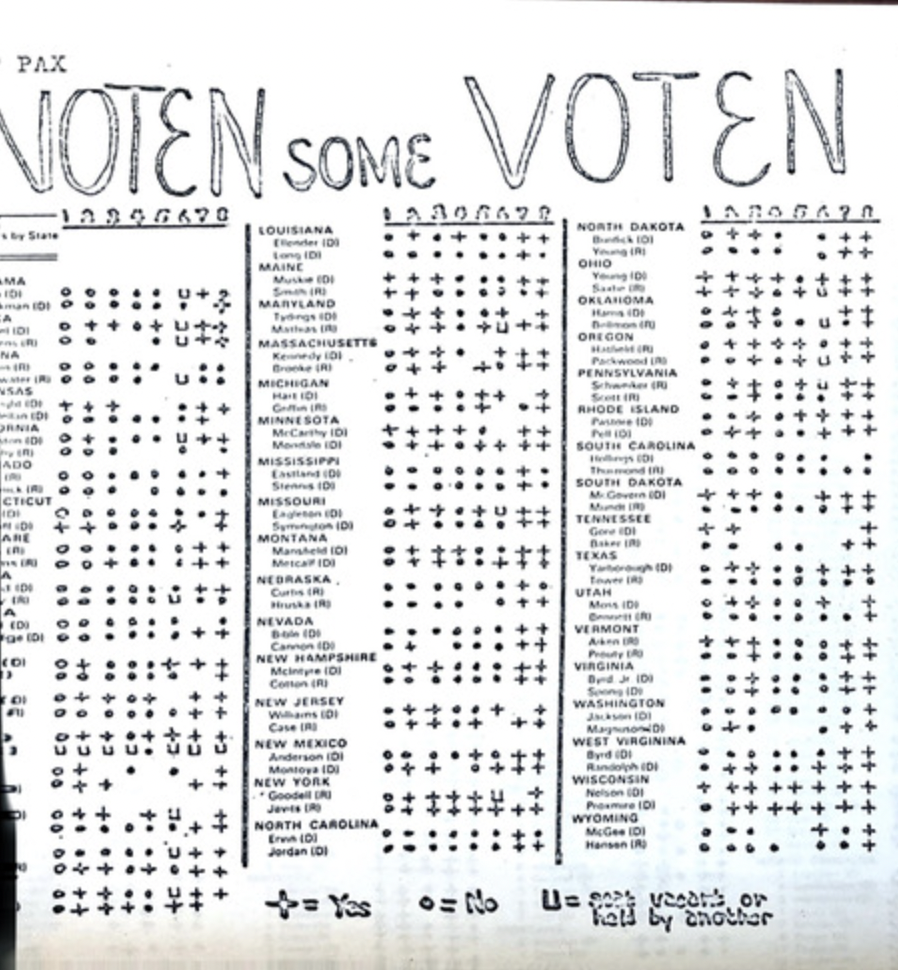

At one point, CPW was scheduling over 150 appointments daily with Congressmen to meet with volunteer lobbyists. To maximize impact of these appointments, CPW contributors compiled exhaustive briefings and distributed them to lobbyists before their meetings. Information included “brief biographical sketches of their congressmen, current stands on the major peace bills, a summary of voting records, the Congressman’s re-election situation, and other information.” Lobbyists were also briefed on “lobbying techniques and […] etiquette.”

After the meeting, lobbyists filled out a debriefing form that funneled up-to-date information on Congressional stances back to CPW analysts. This allowed the organization to keep a tight following on Congressional rationale to justify or criticize the war, and these updates were quickly incorporated into briefing reports for future lobbyists.

Information Management: The Dartmouth Kiewit Computer and Social Sciences Computing

To efficiently leverage the massive amount of data it collected and analyzed, Continuing Presence in Washington made ample use of the Dartmouth computer in Hanover as well as through a teletype installed in Washington. The computer enabled quick communication between the Hanover and Washington CPW locations as well as with offices at other universities, some of which had direct access to the computer.

The computer shined the most in briefing preparation and debriefing analysis. The organization needed to manage biographical information, voting records, and positions on major bills for a large number of politicians, and it needed to be able to access and distribute this information quickly. Bidwell confirmed this in his interview, noting that “the claim was […] there'd never been any computerized database of voting records, so that's what this was about.”

CPW made operational adjustments to optimize its computer usage. For example, per a CPW pamphlet, the debriefing forms were “designed specifically for computer analysis” (CPW, n.d.). Below is a sample debriefing form. It presents numbered, discrete options to characterize lobbying experiences rather than freeform responses. By channeling data into limited categories, it is more easily analyzed by quantitative computational techniques. Adjustments to data collection like these reflect the introduction of computers into the social sciences – Gerd Gigerenzer notes that “the emphasis has shifted from collecting qualitative observations to quantitative data” (Gigerenzer 2001). Continuing Presence in Washington followed this trend to remain effective in the political realm.

Division of Labor: CPW in Hanover, Washington, and Beyond

Continuing Presence in Washington quickly grew beyond the Hanover sphere and had volunteers working in a number of locations.

The Hanover office served as the primary interface of the Dartmouth and Upper Valley communities. The team recruited volunteers to lobby in Washington or in local district offices, assisted in organizing transportation and housing, and importantly, connected Dartmouth alumni with the cause and solicited their financial and volunteer support through scheduled dinners and events. “Hanover CPW” also maintained contact with ten to fifteen established CPW chapters at other universities and served as the central hub for information and access to the Kiewit computer. Hanover CPW made successful contact with over seventy universities. This collaborative function established CPW as a forming member of a number of national coalitions, the National Coalition for a Responsible Congress and the Coalition Against the War (CPW, n.d.).

The Washington office was the primary landing site for volunteers during their stays in Washington. It was staffed by approximately fifty students from Dartmouth and other universities. Washington CPW had a Trustee Board and Executive Board, the latter having committees for Policy Research, Briefing and De-Briefing, Group Contacts (interfacing with other CPW and antiwar organizations), Public Relations, Finance, Housing, Office Management, and Volunteers. Aside from preparing the volunteer briefings and reporting the debriefings into the computer system, Washington CPW also spearheaded collaboration with other Washington-antiwar organizations.

While this structure was effective for the first three weeks of operation, a problem arose when other universities began to dismiss for summer break. Continuing Presence in Washington started losing manpower outside of its primary locations and needed a strategic shift to keep up activity outside of Hanover and Washington.

As a result, CPW developed local offices staffed by Dartmouth alumni and students who were home for the summer. Local offices established a physical plant, recruited lobbyists and permanent volunteers, made fundraising campaigns, and completed the briefing, appointment-scheduling, housing, and transportation work that the Hanover and Washington locations completed. Local CPWs also organized local dinners to rally alumni and keep them engaged — shown below is a list of local CPW representatives that could connect interested local volunteers with opportunities in Washington. Below as well is a mailer that demonstrates CPW's widespread recruitment efforts.