Joining ROTC at Dartmouth During the Cold War Era

What pressures did men face as they decided whether to join ROTC?

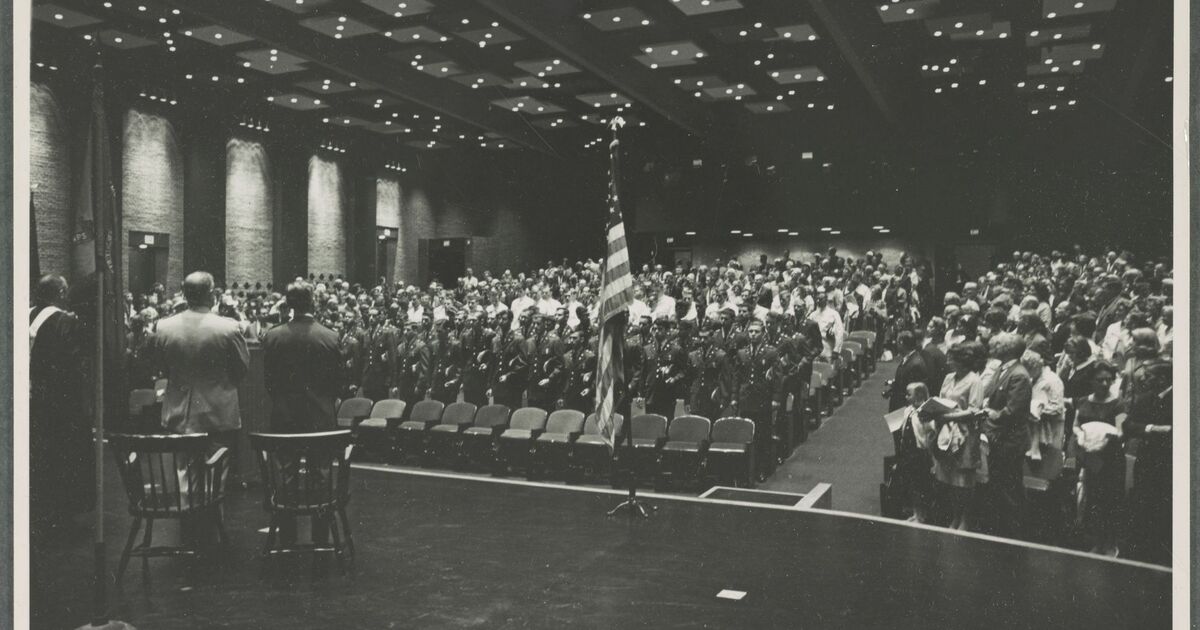

Partnered with the rise of militarism in the fabric of Dartmouth culture, the 1950’s and 1960’s brought with it a rapid increase in participation in ROTC. This begs the question: why did so many men join ROTC at Dartmouth in the Vietnam Era? The answer to this question was deeply intertwined with the political context of the Cold War. As we reviewed DVP interview transcripts of Dartmouth ROTC alumni, we found that on the surface their motives could be classified into four categories: a fear of being drafted, a monetary incentive, a sense that military service was the norm, or feeling duty-bound to serve their country. We consider the unique politics of the 1950’s, ‘60’s, and ‘70s in tandem with the decisions made by Dartmouth students to join ROTC.

With increasing U.S. involvement in Vietnam, draft-age men began to feel as though the likelihood that they would serve in the military increased. While the draft had been active since 1948, it transitioned from a force whose purpose involved internally-oriented national security during the Cold War to what could be described as externally-oriented national security during the Vietnam War. For instance, between 1965 and 1966, the number of men being called into service more than tripled. The question became how rather than whether a man would come to serve in the military: would they join voluntarily and thus have a say in where and how they served? Or would they leave it up to fate to determine whether or not they would be called upon to serve in Vietnam? This distinction, deemed “choice or chance” by Amy Rutenberg, was at the center of many men’s motivations to join ROTC. Dartmouth men seemed to view ROTC as an escape from the reality of the draft. As James Laughlin ‘64 put it, ROTC was “a way of keeping yourself out of the clutches of the draft.”

The History Behind the Commonality of Joining ROTC: It "Just Seemed Normal"

In 1960, Time published an article entitled "For College Students" detailing how they should be thinking about military service. They wrote, "it behooves you, therefore, to look over the field [of service branches] first and decide, while the choice is still yours, whether or not any of the many voluntary plans suits your purposes better than the draft." On May 16, 1961, Gilbert R. Tanis, the Executive Officer of the College, wrote to Time to request 900 copies of the article to the freshman class. This was the mindset that Dartmouth men entered college with throughout the 1960's: join ROTC and have a say in your military service, or risk being drafted and sent into combat.

"You certainly will be drafted before you reach 26 unless you qualify for a specific deferrment... or unless you enlist." -Time article for college students, 1960

David Dawley ‘63 described being in ROTC as “just sort of a Mickey Mouse kind of deal.” When he matriculated to Dartmouth in 1959, it felt like everyone was in ROTC–it was simply part of the college experience. Dawley was at Dartmouth during a unique period of time when ROTC was the norm, sandwiched between two periods of time when it was not. Some joined ROTC simply because most of their friends were in it. But why was ROTC so common? The omnipresent force of the draft loomed in the background, flanked by the fathers of the young men who had served in World War II. While some men might have joined ROTC because of the number of their friends who were in it, the question becomes why so many of their friends had chosen to join.

A Classist System: Financial Motivations to Join ROTC

It is well established that the Vietnam War draft was not equitable on many metrics, including class. Working class and poor men made up 80% of the 2.5 million enlisted men who served in Vietnam. They had far fewer resources available to them to avoid service or to rise in rank to enter the war as an officer. Some Dartmouth alumni recall joining ROTC because of the scholarships available through the program. Many applied to a Navy ROTC scholarship at the same time that they applied for college because they would not have been able to afford college tuition otherwise. Their choice to apply for this scholarship was likely influenced by their higher probability of being drafted in addition to granting them the ability to attend college. Even ROTC cadets who did not have scholarships were paid $50 a month, equivalent to almost $500 in 2023. This stipend provided significant financial assistance to cadets. While it seldom served as a student’s primary motivation for joining ROTC, many noted it as an added benefit. Overall, though, joining ROTC was influenced by class such that poorer men were more likely to need the money and more likely to be called to serve even without ROTC.

Following in Their Fathers’ Footsteps: Fulfilling Their Duty to Serve

Men who came of age during the Vietnam War were largely the children of fathers who had served in World War II. This idea of a military tradition was fed to these men as children, as their fathers and other veterans were glorified for their service. Going beyond a desire to avoid being drafted or to enter the military as an officer, many Dartmouth alumni expressed being compelled to serve because it was, as Peter Sorlien ‘71 said, “the honorable thing to do.” This feeling of being duty-bound to serve one’s country did not translate into also feeling support for U.S. involvement in Vietnam, however. Steven Sloca ‘66 noted that despite having become an opponent of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, he remained steadfast in his conviction that it was his duty to serve his country whether or not he believed in the cause. Having grown up as witness to the celebration of American militarism, that serving one’s country was the courageous and honorable choice was ingrained in these men.

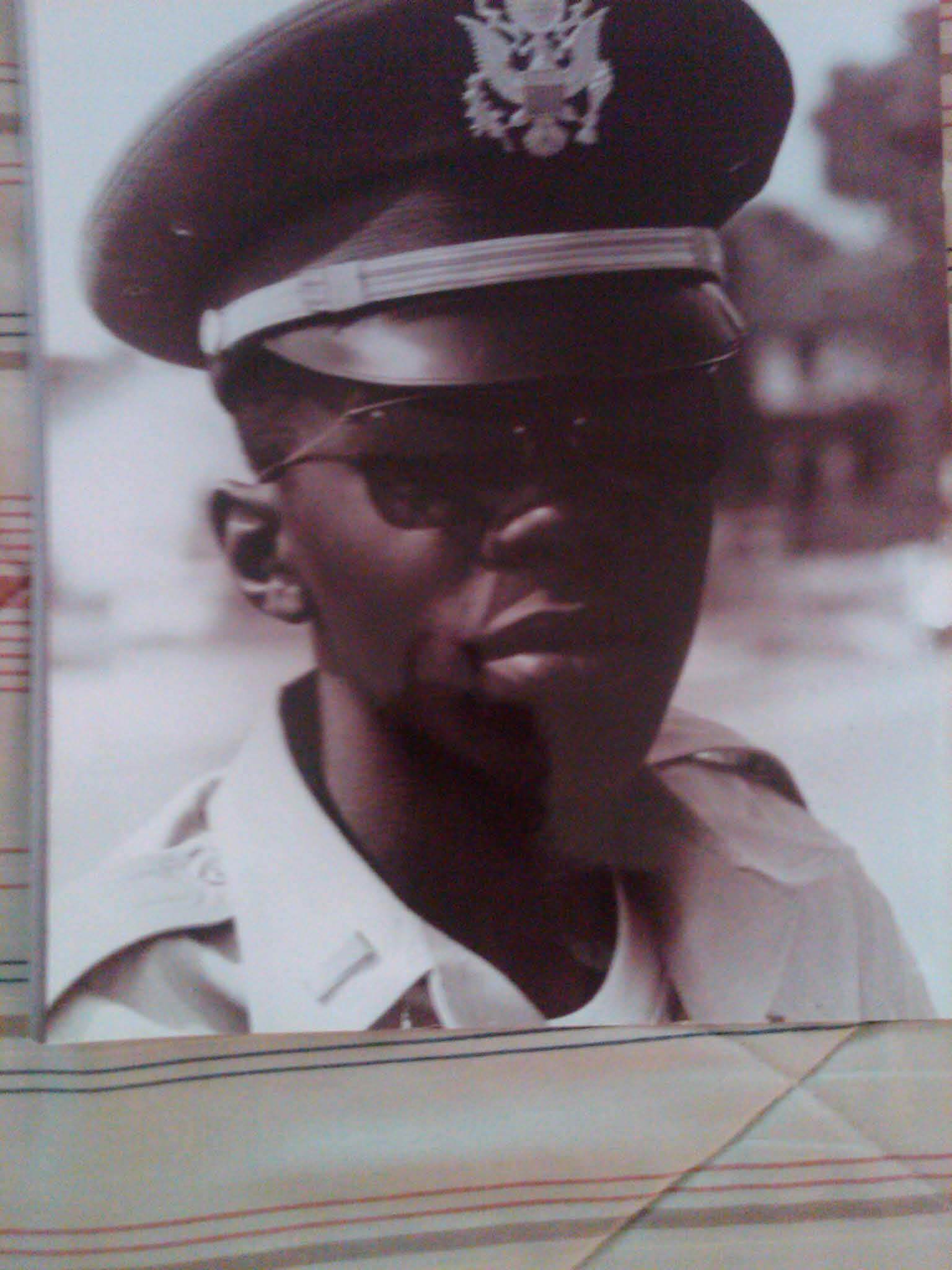

Case Study: Joe Nathan Wright '68

As a Black man who grew up in segregated Charleston, South Carolina, Joe Nathan Wright ‘68 spoke wistfully of his time at Dartmouth College where he was in Army ROTC. When it came to Wright’s motivation for joining ROTC, like many others, Wright mentioned a desire to avoid the draft, to enter the military as an officer rather than a draftee. He noted that he needed the money as well. However, unlike others, while his father had served in World War II, he did not speak of a desire to follow in his footsteps, likely because his father was not all that present in his life.

Raised by a single mother, Wright found his heroes in history books and developed a profound sense of duty to serve his country. He said that he joined ROTC because he had always wanted to be a military officer. When I asked him why, he spoke of the nobility of the U.S. military. He noted that, “being Black, I thought there was something special about hundreds of thousands of people risking their lives and dying” at Gettysburg and Vicksburg during the Civil War. He said, “it seemed to me that the United States Military had freed more people, fed more people, and protected more people than any other force in the history of the world.” He saw the U.S. military as a force for good and that goodness is what drove him to want to be a part of it.

Further, when Wright matriculated to Dartmouth in 1964, the Civil Rights movement was in full swing and Wright was aware of the rarity of Black military officers. He hoped to change that. He was aware that some people might ask why he and other Black Americans would choose to serve a country that has “so often let them down.” He viewed himself as a sort of stepping stone on the United States’ “journey to a more perfect union.” Thus, Wright’s desire to do his duty and serve his country was interconnected with his taking a step forward towards making the U.S. a better and more inclusive place, and both drove him to participate in Army ROTC.

The recording and transcript of the DVP interview with Joe Nathan Wright '68 can be found on the Our Interviews page.